Waste Management and Economic Growth

World Cities Summit Issue, June 2008

Having developed its industrial base and achieved high economic growth in the last four decades, current day Singapore is highly urbanised and industrialised. This has had a major impact on the environment—more pollution and waste generated.

The challenge is especially great for Singapore as it is an island city-state with an area of only 704 square kilometres and a population of 4.59 million people. Its population density of over 6,500 persons per square kilometre is the fourth highest in the world, after Monaco, Macao and Hong Kong. To remain attractive, it is essential for Singapore to maintain a good quality living environment, where standards of public health meet the growing expectations of our local population as well as those of investors, tourists and a highly mobile international and local talent pool of people.

Thus, Singapore is highly conscious of the environmental pitfalls of industrialisation and, since the early days of industrialisation, had developed its own integrated approach to environmental protection and management with the aim of ensuring that industrial development was not at the expense of the living environment. The key strategies are prevention, enforcement and monitoring.

Firstly, great emphasis is placed on judicious land use planning and development and building plan control for housing, commercial, industrial and recreational uses as well as water catchments. Secondly, investments in waste collection and treatment infrastructure are made in tandem with industrial and urban developments to minimise pollution to our land and waters. Thirdly, legislation enacted to control pollution is applied judiciously. This is complemented by close monitoring of ambient air, inland and coastal waters to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the environmental pollution control programmes and by strict enforcement to ensure that waste collection and treatment facilities are properly operated and maintained, and the standards and requirements complied with.

In addition, public awareness and education programmes are conducted to educate the public on the protection of the environment. This multi-pronged approach has enabled Singapore to achieve and maintain a clean and healthy environment, even as the economy continues to grow.

THE SINGAPORE GREEN PLAN

The need for a fresh approach to environmental management was felt towards the end of the eighties. Over the years, there has been a shift of emphasis from a “top-down” approach towards self-regulation by the industries through various incentive schemes; the traditional “command and control” approach, although proven useful, has become increasingly costly to both government and industry.

By then, basic infrastructure for the removal and disposal of solid waste, sewage and wastewater were in place. Air and water pollution were regulated through planning controls and emission standards. However, an increasing population with higher expectations and growing appetites continued to exert pressure on Singapore’s limited capacity to cope with resource consumption and waste generation.

At the same time, there was international consensus on the need to take action on global environmental issues, such as global warming, the protection of the ozone layer, and the preservation of wildlife and prevention of coastal pollution, in which Singapore was an active participant and advocate.

These reasons paved the way for the Ministry of the Environment (subsequently renamed the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, or MEWR) to draw up and publish the Singapore Green Plan (SGP) in May 1992. The SGP charted the strategic directions that Singapore would be adopting to achieve its goal of sustainable development. It was presented at the June 1992 Rio Earth Summit in Brazil.

To keep the SGP relevant amidst the changing economic and environmental landscapes, a review was initiated and the SGP 2012 was launched on 24 August 2002.

The SGP 2012 conveys the message that the new challenge Singapore now faces is no longer environmental performance, but environmental sustainability. This updated master plan charts Singapore’s approach to achieve environmental sustainability over the next 10 years and sets out the broad directions and the strategic thrusts that will help ensure Singapore’s long-term environmental sustainability. The SGP was reviewed in 2005 and an updated edition was published in February 2006.

THE SOLID WASTE CHALLENGE

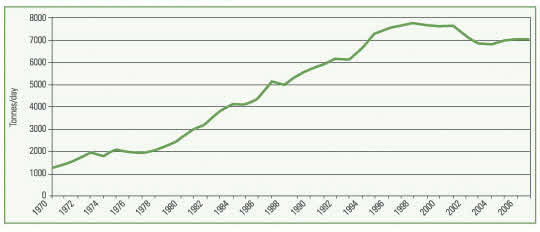

With limited land area and high population density, it is not surprising that the disposal of municipal solid waste poses a major challenge to Singapore. The strong economic growth achieved in the last 40 years of development has resulted in a corresponding explosion in waste generated and, if not properly managed, would have caused degradation to Singapore’s environment. In 1970, about 1,300 tonnes of solid waste were disposed of daily; by 2000, this had increased six-fold to 7,600 tonnes per day (Figure 1). The problem was further compounded by Singapore’s warm and humid climate, which makes refuse extremely putrefiable. Refuse has to be removed and disposed of quickly, efficiently and safely before it gives rise to smell nuisance, infectious diseases and other public health hazards.

Furthermore, if the rate of waste disposal were to continue to grow as it did, scarce land resources would need to be set aside to build more expensive incinerators and landfills. This was clearly not sustainable.

FIGURE 1. TOTAL WASTE DISPOSED (1970 TO 2007)

In order to cope with Singapore’s ever-increasing amount of waste, a new landfill was created by constructing a 7-kilometre perimeter rock bund to enclose part of the sea between Pulau Semakau and Pulau Sakeng, two of Singapore’s offshore islands. On-site work on the project costing S$610 million started in April 1995, and operation began in April 1999, after Singapore’s only landfill at Lorong Halus was exhausted in March 1999.

THE SEMAKAU LANDFILL

In order to cope with Singapore’s ever-increasing amount of waste, a new landfill was created by constructing a 7-kilometre perimeter rock bund to enclose part of the sea between Pulau Semakau and Pulau Sakeng, two of Singapore’s offshore islands. On-site work on the project costing S$610 million started in April 1995, and operation began in April 1999, after Singapore’s only landfill at Lorong Halus was exhausted in March 1999.

Semakau Landfill is expected to meet the country’s solid waste disposal needs beyond year 2040. Presently, about 2,000 tonnes of waste, including construction waste, non-hazardous industrial waste and inert ash, are transported daily from the Tuas Marine Transfer Station to the landfill.

Semakau Landfill is one of the few landfills in the world to be located so far away from the mainland. Landfills are usually situated close to the mainland, because it makes transportation easier and less costly. However, due to land scarcity in Singapore, locating a landfill offshore was the only possible option.

Semakau Landfill covers a total area of 350 hectares and has a landfill capacity of 63 million cubic metres. The bund is lined with a layer of impermeable membrane and marine clay to prevent any leachate within the landfill area from affecting the surrounding environment.

FIGURE 2. SEA ROUTE TO SEMAKAU LANDFILL

During construction, silt screens were used to prevent the construction activities from contaminating the ecosystem in the vicinity of the landfill. The mangroves of Pulau Semakau which were affected in the construction process were replaced and replanted on two plots of mangroves of about 14 hectares located outside the periphery of the sanitary landfill. Over 400,000 mangrove saplings were replanted in the process.

Besides helping to preserve the rich mangrove groves around the sanitary landfill facility, the mangroves also act as biological indicators of the water quality around the facility. With all the pollution prevention measures put in place, the mangroves have thrived and so have the biodiversity of the eco-system around the facility.

Singapore chose to protect the environment as well as create a sanitary landfill out of two islands without impacting the surrounding environment and ecology. The rich biodiversity around the sanitary landfill shows that development and environmental protection can co-exist and need not be mutually exclusive.

SUSTAINABLE SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT

The National Environment Agency (NEA) has, in close partnership with key stakeholders in the Private, Public and People (3P) sectors, adopted strategies and programmes to address this problem. These strategies are: Volume Reduction through Incineration; Waste Recycling and Reduction of Landfilled Waste; and Waste Minimisation.

These measures have increased the overall recycling rate from 40% in 2000 to 54% in 2007, putting the country in a good position to achieve its target of 60% as outlined in the SGP 2012.

Strategy 1: Volume Reduction

Before 1979, all waste was disposed of in landfills carved out of swampy areas on the main island of Singapore. The situation was becoming precarious—projections showed that space for landfills would run out very quickly as waste quantities grew in leaps and bounds. Studies indicated that waste-to-energy incineration plants were the way to go in our situation. Being able to reduce waste volume by a drastic 90% in a short time and in facilities requiring relatively small footprints was clearly an ideal solution to our resource-scarce situation. The first incineration plant was commissioned in 1979. Since then, three other bigger plants followed in quick succession—1986, 1992 and 2000—to meet the ever-increasing waste loads.

These four modern waste-to-energy incineration plants are fitted with advanced treatment systems to remove acidic gases, dust and other contaminants from the flue gas before it is released through the chimneys. The flue gas is closely monitored to comply with Singapore’s clean air emission standards. Energy is recovered to generate electricity; scrap iron is also recovered. The resulting incineration ash, which takes up only 10% of its original volume, is then landfilled.

Strategy 2: Waste Recycling

Even as incineration offered us an effective, though expensive, technical solution to our waste situation, projections showed that we would have still exhausted all our landfills on the main island by 1999. We therefore had to look beyond, to enclose a sea space eight kilometres south of the main island, and at great expense, to build our sole remaining landfill off the shores of Pulau Semakau island (see box story).

Moving up the waste hierarchy, the second strategy was therefore to promote waste recycling in the industrial/commercial sectors and in households, to reduce the waste disposed of at the incineration plants and landfill. This was done through a three-pronged approach of engaging the industry, community and schools.

a) Industry Participation

Less than half of the waste disposed of in Singapore comes from the industrial and commercial sectors. Such waste includes metals, horticultural and wood waste, and paper waste. Recycling in the industrial and commercial sectors helps avoid the gate fees charged at the waste disposal facilities and thus contributes directly to the bottom line. The NEA promotes waste recycling by conducting talks, running awareness programmes targeted at businesses, and providing recycling information and data. It also worked with the largest owner of industrial land and ready-built factories, JTC Corporation, to set up recycling facilities in all its 21 flatted-factory and nine terraced-workshop industrial estates.

The Singapore Land Authority also helped by allocating some 20 hectares of land at Sarimbun for recycling activities. Sitting on a closed landfill, the Sarimbun Recycling Park (SRP) is operated by NEA. To date, the SRP has been well utilised for various recycling activities, such as composting of horticultural waste and recycling of construction and demolition waste.

NEA administers the S$20 million “Innovation for Environmental Sustainability” (IES) Fund that was set up by the Government in 2001 to promote the adoption of innovative environmental technologies that contribute towards Singapore’s long-term environmental sustainability. In this regard, waste minimisation is one area targeted by the IES Fund. To date, 15 Singapore-based companies had tapped the IES Fund for funding of several waste management and recycling test-bedding projects. Some of these projects include the production of pre-cast concrete drainage channels using recycled aggregates; the conversion of horticultural waste into packaging materials; and the processing of ladle furnace slag, a by-product of the steel making process, into road construction materials.

The waste recycling industry in Singapore now includes companies with the capability to recycle and process electronic waste, food waste, wood waste, horticultural waste, used copper slag, construction and demolition waste, ferrous waste and plastic waste.

The major types of non-incinerable waste sent directly to the landfill are construction waste, stabilised industrial sludge, residues and ashes, much of which has been diverted, over the years, for reprocessing into useful materials such as aggregates for reuse. At the same time, industry best practices and “less-waste” design and construction methods have also minimised the generation of such waste sent to the Semakau Landfill.

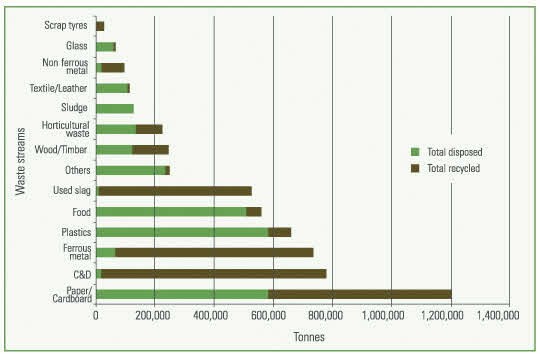

In 2007, some 91% of ferrous metal waste, 98% of construction and demolition waste, 41% of horticultural waste and some 51% of paper waste were recycled (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. WASTE GENERATION IN SINGAPORE

b) Reaching Out to the Community

Changing mindsets and influencing behaviour is important for sustainability, but this takes time. To do so, NEA has been engaging residents, grassroots organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and schools to impress upon the community the need to practise the 3Rs—reduce, reuse, recycle—for resource conservation and to achieve a sustainable waste management system. One such awareness campaign is the annual Recycling Day, which aims to reinforce the need to recycle waste by involving schools, community, NGOs and recycling companies.

NEA launched the National Recycling Programme (NRP) in April 2001 to provide a convenient means for residents living in public and private housing estates to recycle their waste. Under the NRP, public waste collectors are required contractually to provide recycling bags or bins to every household for storing their recyclables and to collect the recyclables door-to-door and fortnightly on scheduled days.

In addition 1,600 sets of centralised recycling depositories have been placed in the common areas of all public Housing and Development Board (HDB)1 housing estates to complement the door-to-door collections. This covers about 85% of the population centres of the country. With approximately one set to every five blocks of flats, most residents would be able to access these centralised recycling depositories within 150 metres from their flats to deposit their recyclables at any time of the day.

This network is supplemented by another 2,200 recycling bins placed in public places with high human traffic. Such places include locations outside train stations, food courts and food centres, bus interchanges, the airport, and pedestrian malls.

c) School Involvement

Environmental awareness has to be inculcated from young. As such, Singapore’s waste management story is incorporated into the school syllabus, including visits to NEA’s incineration plants and the Semakau Landfill.

NEA launched the Recycling Corner Programme (RCP) for schools in September 2002 to inculcate the habit of the 3Rs in students. Recycling bins for paper, drink cans and plastic bottles are placed at Recycling Corners located within school premises. As of 2007, 95% of all schools have recycling facilities.

Under the RCP, students take charge of the Recycling Corners and put up interesting information about the 3Rs. These activities help to generate interest and foster a keener sense of ownership. Activities with recycling themes are held regularly to sustain interest, including competitions, environmental camps, field trips, workshops, and speech writing contests on different aspects of the environment, including waste minimisation and recycling.

To instil a sense of environmental ownership of the recycling programme, students are identified and separately trained to be Environment Champions. These Champions are responsible for various environmental programmes in school such as conducting talks on the environment, and assisting in the planning, organisation and running of recycling and other environmental activities.

Strategy 3: Waste Minimisation

While incineration and recycling are end-of-pipe solutions, the third strategy of waste minimisation or reduction is aimed specifically at cutting waste at source, that is, even before it is produced. This helps close the waste loop by providing us with the means to move closer to our ideal of a zero waste society.

An initiative under this strategy is the Voluntary Packaging Agreement. The Agreement is aimed at reducing packaging waste from the producers’ end. With packaging waste making up almost a third of Singapore’s household waste, this initiative offers great potential for waste reduction. The Agreement is based on the principle of product stewardship, in contrast to the legislative approach which imposes a high compliance cost on industry. This approach directly engages industry players to assume greater corporate responsibility for their packaging waste in a non-prescriptive and cost-effective way.

On 5 June 2007, NEA signed Singapore’s first Voluntary Packaging Agreement for the food and beverage industry which includes five industry associations representing more than 500 companies, 19 individual companies, two NGOs, the Waste Management and Recycling Association of Singapore and the four public waste collectors. This Agreement seeks to secure the commitment of key players in the packaging supply chain, brand owners, manufacturers, importers, retailers and recyclers, and also offers industry a platform to discuss and work together on feasible, cost-effective solutions to reduce packaging waste.

Another initiative to reduce waste is the Bring Your Own Bag Day campaign, launched in April 2007. The first Wednesday of every month has been designated “Bring Your Own Bag Day”. Shoppers are encouraged to use reusable bags so as to cut down on wastage of plastic checkout bags that are taken and discarded without being reused such as for lining waste bins. Shoppers needing a plastic bag are encouraged to donate 10 cents towards the Singapore Environment Council to help finance its environmental activities. Shoppers are also encouraged to decline bags when making small purchases.

CHALLENGES AHEAD

Singapore has always placed a strong emphasis on having a clean environment and pollution-free air, land and water, and the challenges facing Singapore ahead are to maintain a clean and green environment amidst rapid economic progress. To overcome these challenges, Singapore must constantly innovate and optimise its resources.

The way forward is to reduce the waste disposal rate through waste recycling and waste minimisation at source.

As the economy and population continue to grow and consumption patterns change, waste generation is expected to increase. However, NEA is convinced that economic growth need not mean generating more waste. The per capita municipal solid waste disposed of has decreased from 0.94 kg/person/day in 2003 to 0.88 kg/person/day in 2007, suggesting that Singapore is making progress “Towards Zero Landfill” and demonstrating that economic development does not have to mean more waste generated.

In the early days of industrialisation and economic growth, the Singapore Government adopted the most cost-effective solutions at the time to handle the increasing amounts of solid waste being generated in the country. As waste quantities continue to increase with the economy’s robust growth, the way forward is to reduce the waste disposal rate through waste recycling and waste minimisation at source. At the same time, NEA will continue to actively engage and educate the 3P sectors—People, Private and Public sectors—through various community programmes and campaigns to achieve a clean and sustainable living environment.

Through our multi-pronged strategies and sustained efforts, we hope to ensure that Singapore remains as a model of sustainable development in the region.

NOTES

- The Housing and Development Board is Singapore’s public housing authority and a statutory board under the Ministry of National Development.