A City in a Garden

World Cities Summit Issue, June 2008

In the 1960s, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew mooted the creation of a clean and green environment to mitigate the harsh concrete urban environment and improve the quality of life in the city. This was the beginning of Singapore’s development into a Garden City.

As a result, Singapore’s clean and green environment has allowed us to meet the lifestyle and recreational needs of an increasingly affluent population, and enhanced Singapore’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign businesses and talents. Our green policies have contributed to the transformation of Singapore into a distinctive and vibrant global city.

Going forward, the plan is to evolve Singapore into a City in a Garden—a bustling metropolis nestled in a lush mantle of tropical greenery (Figure 1). To do this, we will be adding more sophistication to our greenery plan, conserving our natural heritage, and involving the community.

FIGURE 1. A CITY IN A GARDEN—A BUSTLING METROPOLIS NESTLED IN A LUSH MANTLE OF TROPICAL GREENERY

A MORE SOPHISTICATED GREENERY PLAN

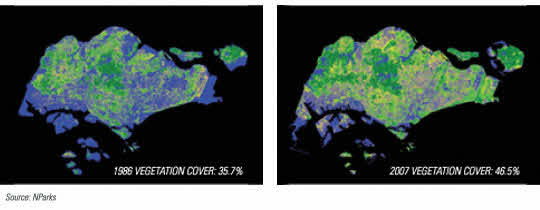

The challenge of greening a small city-state with a land area of only 700 square kilometres and a population of 4.6 million (and still growing) is space. However, green space need not necessarily suffer at the expense of economic and population growth. While land is scarce, with careful planning, Singapore has been able to commit 9% of the total land area to parks and nature reserves. Between 1986 and 2007, despite the population growing by 68% from 2.7 million to 4.6 million, the green cover1 in Singapore grew from 35.7% to 46.5% (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. GRADUAL VEGETATION INCREASE FROM 1986 TO 2007. DARK GREEN AREAS: TREE CANOPY COVER; LIGHT GREEN AREAS: SHRUB COVER/GRASSLANDS. BASED ON DATA FROM NORMALISED DIFFERENCE VEGETATION INDEX MAPS

The importance of greenery for a quality living environment has been underscored in Singapore’s Master Plan 2003. The Master Plan, drawn up by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) to steer Singapore’s urban development in the subsequent 15 years, incorporated a new Parks and Water Bodies Plan with these guiding principles:

- Plan for a hierarchy of parks distributed throughout the island, from larger parks with more facilities, to smaller parks near homes, with a guideline of 0.8 hectare per 1,000 population provision.

- Cluster groups of parks with complementary ecosystems and activities, like wetlands, hill parks, tropical rainforests, and connect them where possible to give a more holistic experience.

- Bring people closer to nature and, where possible, integrate nature areas within parks

- Plan for an island-wide network of green links to connect parks and water bodies with residential areas.

The matrix of park connectors as green links and recreational corridors among parks is one of the ways to expand green space in the city. The park connector network is a series of seven connecting bikeways or green paths. Our target is to build 200 kilometres of park connectors by the year 2015, covering seven closed loops for recreational walking, jogging and cycling activities. Properly integrated with their surrounding areas, the park connectors will enhance the sense of green space throughout the city. The first loop of 42 kilometres, which was completed in December 2007, is known as the Eastern Coastal Park Connector Network. It allows users to walk, jog and cycle through idyllic coastal areas, six parks and residential heartland areas. This park connector network has been well-received and was the venue for the first night-time marathon in Asia in May 2008.

Similarly, the Public Utilities Board (PUB) has opened up and developed its water bodies for recreational activities. The Active, Beautiful and Clean (ABC) Waters Programme is one such initiative, where the objective is to break down some of the harsh concrete walls of water canals, and landscape them for better integration with surrounding parks and green space. The pilot project, completed in April 2008 along the Kallang River, complements a park connector, and demonstrates how such projects can dramatically transform Singapore’s landscape and enhance green and water-based recreational space for the residents.

Skyrise greenery is another example of how we can add new dimensions to the green space in the city. While roof-top and vertical greenery is not a new architectural phenomenon in Singapore, the increasing adoption of skyrise greenery in new iconic buildings such as the National Library Building, and upcoming projects such as the Eco-Precinct by the Housing Development Board (HDB) and the Integrated Resort in Marina Bay augurs well for the development of skyrise greenery in the city. Ongoing research by the National Parks Board (NParks), to identify plants and planting medium to ease maintenance of skyrise greenery, aims to contribute to developments in this area.

The matrix of park connectors as green links and recreational corridors among parks is one of the ways to expand green space in the city.

As the population’s expectations become more sophisticated, there is a need to develop a wider range of parks and recreational amenities. An important focus of NParks has been to develop our parks into natural gravitational points for play and leisure. While ensuring that ample green space has been set aside to cater to those who seek the pleasure of a simple, idyllic green hideout from the hustle and bustle of the city, we are also selectively developing parks along thematic lines. For instance, the Jacob Ballas Children’s Garden at the Singapore Botanic Gardens which opened in October last year was designed as a haven for children below 12 years old. HortPark was officially opened in May 2008 as a one-stop gardening hub for gardening lovers and aspirants. Other projects such as the Fort Canning Park within the city centre will be better connected to the National Museum and the Bras Basah area to improve its vibrancy as a venue for the arts and culture. The new Sengkang Riverside Park will feature a theme of fruit trees and water recreation, while the upcoming new Admiralty Park will have a nature appreciation and conservation component. There will also be a new extreme skate park for those seeking thrills and excitement within a green setting.

Our biggest commitment is the Gardens-by-the-Bay project. This is a plan to develop three world-class gardens on prime land around the Marina Bay waterfront. The first phase of the project, which is to develop a 52-hectare garden at Marina South, has started and is targeted to be completed by 2011. This project will incorporate groundbreaking ideas aimed at enriching the lifestyles and recreational activities of Singaporeans and tourists through edutainment opportunities in a sustainable garden environment.

So far, some 91% of park users surveyed in 2006 were satisfied with the parks in Singapore. There is also a rising trend of tourists visiting our parks and nature reserves. Surveys by the Singapore Tourism Board show that the Singapore Botanic Gardens ranked sixth in terms of local attractions in 2006. A good measure of how well we develop and manage our greenery plan will be reflected in how well we sustain, and indeed improve, these indicators.

CONSERVING OUR NATURAL HERITAGE

Singapore’s rapid re-development as an urban city is matched by increasing calls for urban planners to develop a “soul” for the city. A large part of this will involve retaining the essence or heritage of the old city. Likewise, in developing Singapore as a city in a garden, we are moving beyond paying attention to mere infrastructure to conserving the natural biodiversity in the city.

Given our small land area and the need for economic growth, we have to adopt a pragmatic approach in balancing development and biodiversity conservation. Our aim has been to create a unique conservation model that champions environmental sustainability in a small urban setting. Fortunately, Singapore is a city rich in biodiversity despite our small land mass. The island has some 360 species of birds, which is slightly more than 60% of the 568 species listed in the United Kingdom or 75% of the 467 species found in France. Interestingly, some species thought to be extinct on the island, like the Oriental Pied Hornbill, are now establishing healthy colonies here because of the lush green environment. Nestled in the midst of the Indo-Malayan rainforest (one of three last remaining rainforest blocs in the world), Singapore is well-placed to showcase the richness of the region’s rich botanical biodiversity in an easily accessible urban setting.

It is in this context that the Government adopted the policy to legally protect representatives of key indigenous ecosystems. We have four Nature Reserves, namely, the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (lowland dipterocarp forest), the Central Catchment Nature Reserve (including freshwater swamp forest), Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (mangroves) and Labrador Nature Reserve (coastal hill forest). The Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Labrador Nature Reserve were gazetted in January 2002. Together, the four nature reserves cover more than 3,000 hectares or 4.5% of Singapore’s land area. We are probably unique in being one of the few cities with nature reserves within its urban setting. In addition, one of the reserves, the Sungei Buloh Wetland, holds the distinction of being an ASEAN Heritage Park, as well as an important link in the chain of stop-over sites for migratory birds from as far as Siberia.

While the nature reserves are sustainable in terms of size, we also need to ensure their sustainability in terms of quality, that is, the species surviving within them and how they react to the long-term impact of environmental change. The Smithsonian Center for Tropical Forest Science has been conducting research of this nature in the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve for the past decade. NParks also conducts our own periodic biodiversity surveys of the nature reserves for this purpose. Results from such studies and surveys will help us to formulate management strategies for the long-term sustainability of our nature reserves within our unique urban setting. A major project that is being planned is to create an eco-link over the Bukit Timah Expressway which is located close to the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve to mitigate the negative effects of fragmentation and genetic erosion in the Reserve.

Outside the nature reserves, Singapore’s network of green space, streetscape, park connectors and water bodies covers more than 4.5% of our land areas. With proper management, these areas can also be optimised to enhance our urban biodiversity. We have programmes such as the Heritage Tree Programme and Heritage Road Programme to conserve mature trees in the city. One of the projects in the pipeline includes widening the diversity of regional native plant species used in roadside, park and park connector planting. The most recent initiative is a project to set up a dipterocarp arboretum in an urban setting at Yishun Park. We will also need to better build up expertise to create eco-habitats within our urban green space. It is envisaged that with the right planting schemes, the park connectors can form a matrix of green links for bird movement within our urban setting. Likewise, PUB’s ABC programme will provide new opportunities to create water-based eco-habitats in the city.

INVOLVING THE COMMUNITY

To truly realise Singapore’s vision of a City in a Garden, it is important that the community shares and takes ownership of this vision and is actively involved in the greening efforts. Many efforts have been made to ensure that NParks’ work is supported by the 3P sectors: people, public sector agencies and private corporations. In 2006 alone, more than 1,000 guided walks, educational talks, events and programmes were conducted as part of our outreach efforts in this area.

We are seeing increased public interest and participation in community gardening efforts. The Community-in-Bloom (CIB) programme, which seeks to cultivate a culture of gardening in Singapore, has received very good support. Since its inception in 2005, the programme has inducted more than 250 gardening groups in the community. What has been most rewarding is how this programme has helped to promote gardening as a hobby as well as build friendship and the spirit of sharing in the community. Our next step is to introduce the CIB-Kids programme. Through partnerships with educators, we hope to inculcate an appreciation for gardening in our young. The Plant-a-Tree programme has also been well-received. Large numbers of individuals and corporations have stepped forward to donate a nominal sum of $200 to plant a tree and contribute towards the wellness of our living environment.

Within the public sector, the Garden City Action Committee has been the main coordinating vehicle for ensuring that public sector agencies such as the URA, HDB, PUB and the Land Transport Authority are well coordinated in their developmental projects and are aligned to the City in a Garden vision.

In the private sector, the global climate change agenda has also seen more corporations take up environmental programmes as part of their corporate social responsibility. The Garden City Fund was set up in 2002 to allow individuals and corporations to donate to the greening efforts of the Singapore. Increasingly, we have been seeing more private sector companies contribute to this Fund which promotes the environmental cause among consumers.

CONCLUSION

New initiatives to energise Singapore’s green space, balance economic development and environmental conservation, and engage community participation at all levels, will further enhance the vibrancy and soul of our City in a Garden. We can look forward to greener days ahead.2

NOTES

- This refers to the area covered by greenery. This is based on a study conducted by the Centre for Remote Imaging, Sensing and Processing (CRISP), National University of Singapore.

- This article was written in April 2008 and since then, our City in a Garden has been further augmented via the release of the draft Master Plan 2008 on 23 May 2008. The key thrusts look towards a transformation into a City of Gardens and Water, where greenery and blue spaces would be increased, extended and pervasive. As outlined in the new Master Plan, greenery will be significantly increased, with proposed park areas being upped from 3,300 to 4,500 hectares, which include new major parks as well. The park connector network will be increased to 360 kilometres of park connectors, inclusive of a 150-kilometre round-the-island loop. A significant proposal will be the harnessing of rustic farmland areas like Kranji and Lim Chu Kang as nature refuges, featuring nature trails, educational programmes, and even waterway boating.