The Twin Pillars of Estate Rejuvenation

World Cities Summit Issue, June 2008

Soon after Singapore attained self-government in 1959, one of its key challenges was to ease a severe housing shortage. The Housing and Development Board (HDB), which was set up a year later to handle this task, opted to provide small and utilitarian flats, which it was able to build quickly and at low cost to house a fast-growing population. Once the housing shortage eased, the Board's challenge was to keep up with the changing needs and aspirations of the people, who were beginning to seek bigger and better flats, and more comprehensive facilities. This is a critical challenge since living in HDB flats is a way of life for most Singaporeans. Today, some 900,000 HDB flats across the island house 8 out of every 10 Singaporeans, where 95% of all HDB dwellers own the flats they live in (see box story on The Home Ownership Programme).

For many Singaporeans, the HDB flat is the single biggest asset they own. Hence, HDB has to continuously rejuvenate and renew its public housing estates to ensure that they remain vibrant and meet the changing lifestyles and growing affluence of Singaporeans. Where functionality was the focus in the building of housing estates in the early days, design and quality have become equally important considerations in HDB’s planning efforts today.

THE HOME OWNERSHIP PROGRAMME

The Home Ownership Programme is the cornerstone of Singapore's public housing. Started in 1964, the programme aims to give Singaporeans a stake in the country and its future, and promotes rootedness and a sense of belonging among Singaporeans, which contributes to the overall economic, social and political stability of the country. It also provides Singaporeans with an asset and a store of value that can be monetised in times of need.

Today, a framework of housing and mortgage subsidies and the availability of Central Provident Fund (CPF)1 savings to aid housing payments, make HDB flats affordable for Singaporean families. Together with comprehensive land use planning, cost-effective design and construction, and responsive public housing policies, HDB has achieved near full home ownership for Singaporeans. This common experience of HDB living thus bonds Singaporeans of different ethnic and socio-economic groups, fostering community cohesion.

For its achievement in the development and administration of the Home Ownership Programme that has benefited Singaporeans and improved their quality of living, HDB received the 2008 United Nations Public Service Award. This Award is given to public institutions for their creative achievements and contributions that lead to a more effective and responsive public administration in countries worldwide.

KEEPING UP WITH AFFLUENT CITIZENS AND CHANGING LIFESTYLES

Public housing in Singapore has been well managed and maintained. Daily cleaning and conservancy works carried out by local town councils, together with regular maintenance and repairs to the buildings, have ensured good standards of upkeep. Nonetheless, more had to be done for the older public housing estates built between the 1960s and the early 1980s. In terms of design, fittings and facilities, they were lagging behind the newer estates. For example, residents living in residential blocks built before the 1990s did not enjoy the convenience of having lifts serving every floor, while residents living in flats completed during the peak construction years from 1981 to 1986 faced maintenance issues such as spalling concrete and water seepage.

Apart from the physical ageing of the flats, there was also the greying of the population in these older estates. As younger residents formed their own nuclear families and moved out, attracted to the latest designs and modern facilities of newer towns, they left behind not only their older folks but also a vacuum in the social and economic life of the estates. Without the economic pull and dynamism of a younger population, the vibrancy and sustainability of older towns were affected. It became urgent to improve the living environment and inject new life, as well as to find a suitable mechanism to effect the needed changes.

CHOOSING AN OPTIMAL SOLUTION

An optimal solution is one that is able to meet and balance key needs. There are two practical options for rejuvenating older estates. The first is upgrading. Upgrading involves improving the physical conditions of the precinct, the building blocks and the interior of the flats to a standard comparable to those found in newer estates. It enhances the living environment for HDB residents and helps to sustain the value of their flats, without uprooting them from their familiar environment and community.

Upgrading has inherent advantages as the affected residents are not required to move out and it is less disruptive to the social and economic life of the community. The relatively minimal displacement involved makes upgrading a less costly and more affordable measure. The results of upgrading are also more immediate and highly visible, which significantly improves the quality of life and well-being of the residents.

Without the economic pull and dynamism of a younger population, the vibrancy and sustainability of older towns were affected.

However, upgrading cannot fully address the needs of some older public housing estates. For example, due to their inherent design, some old housing blocks cannot be retrofitted with lifts which stop on every floor. Residents, including the elderly and the handicapped, would still need to climb some flights of stairs to reach their flats. Upgrading also does not help to improve the population make-up in the estate.

The second option is redevelopment. This involves redeveloping an existing housing precinct by relocating its residents and demolishing the existing flats. Some of the older precincts were built in the earlier years at lower density. Preserving them in their existing layout would perpetuate the sub-optimal use of land. Redevelopment allows the use of land to be intensified—a clear strategic benefit, given Singapore’s land scarcity. Moreover, the land freed up through the clearance of aged blocks enables more flats to be built so that the existing residents can upgrade to new and better homes, and younger families and more activities can be brought in to revitalise the estate.

However, redevelopment may not be financially viable for all old housing precincts. In some cases, there are no suitable replacement sites nearby to resettle affected residents. Redevelopment is also an exercise requiring sensitive handling as it involves major displacement and uprooting. Care has to be taken in planning and implementation to ensure that residents are properly re-housed and existing community ties are not severed along with the demolition of the flats.

Both upgrading and redevelopment have their benefits and shortcomings. Depending on the circumstances, one could yield greater benefits to the city-state and the community than the other. HDB has therefore relied on both approaches to regenerate its older public housing estates.

MAIN UPGRADING PROGRAMME

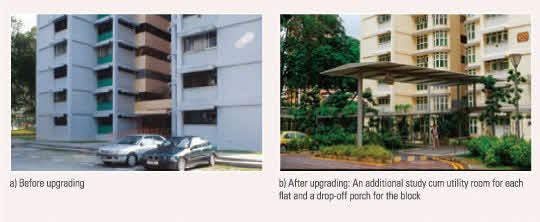

The most comprehensive form of upgrading implemented by HDB is the Main Upgrading Programme (MUP). Launched in 1989, the MUP is targeted at blocks more than 20 years old and aims to improve the interior and exterior of the flats to standards comparable to those in newer estates. Under the MUP, the improvement items comprise a Standard Package of basic works that help to lengthen the lifespan of the flat, such as upgrading toilets/bathrooms, repairing spalling concrete, and improvements to the blocks and precinct, such as lift upgrading and the provision of linkways and drop-off porches. For certain blocks, residents can also opt for additional space or room of about 6 square metres, to be attached to each flat (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. EXAMPLE OF THE MAIN UPGRADING PROGRAMME

As of March this year, 137 precincts involving 946 blocks and a total of about 136,800 flats have been announced for MUP. The acceptance rate of the programme has been high. Of the 137 precincts, 129 have already conducted polling exercises, where 127 precincts or 98.4% have opted for the upgrading programme.

Whether a precinct is upgraded is a collective decision made by the residents. At least 75% of flat owners in a precinct must agree to the programme before upgrading can proceed. This high support threshold is necessary as the MUP requires significant financial commitment from residents and may take up to 21/2 years to complete, during which residents will have to bear with noise, dust and other forms of inconvenience.

To ensure affordability, a large share of the cost of upgrading is borne by the Government. Flat owners are asked to bear a small portion, ranging from 10% to 25% of the total cost, depending on flat type. The cost-sharing policy helps to moderate the demand for improvement works and ensures that only essential works are undertaken. To ensure that even those with limited financial means can afford upgrading, flat owners are allowed to make use of their CPF savings to pay for their share of the cost of upgrading and to stretch their payments over a 10-year period.

As upgrading is done with residents continuing to live in their flats, ensuring their comfort and convenience is an important factor in the implementation stage. The latest construction technologies are employed to reduce the negative impact of upgrading works. Pre-cast or dry construction techniques are used wherever possible to hasten construction works and keep noise and dust levels within tolerable ranges. Additional measures are taken to provide alternatives for residents when the upgrading works are done within their flats; for example, temporary air-conditioned study rooms and rest areas, toilets and washing facilities are provided on site for their use.

The Main Upgrading Programme is an investment in housing infrastructure that enhances the environment and provides a better quality of life for residents.

At the point of inception, the Government noted that the programme would substantially increase its expenditure on public housing over the next 20 years. Nevertheless, it supported the programme, viewing its share of the upgrading cost as a transfer of its budget surplus to the flat owners. It also recognised that the upgrading programme would enhance the market value of the flats—the single biggest asset for most citizens. The programme is also an investment in housing infrastructure that enhances the environment and provides a better quality of life for residents.

The most important element for the success of the upgrading programme is the commitment by both the Government and residents. Firstly, the Government must be prepared to provide the necessary funding support for the programme to be carried out. Although the pace of MUP is dependent on the economic performance of the country and the availability of budget surpluses to fund the programme, the Government ensured that the programme did not grind to a halt when the country was facing an economic slowdown. When the economy improved, it stepped up the programme to enable more residents to benefit from upgrading. Up until 2007, it has spent about S$2.7 billion on MUP.

Secondly, residents must get a real sense that upgrading is meeting their needs. Feedback on their needs and preferences is imperative so that the programme can be tailored accordingly. A working committee for each MUP precinct oversees the project to ensure that the upgrading package is aligned with residents’ expectations before taking it to the poll. HDB also carries out regular surveys of completed MUP precincts to gauge residents’ satisfaction and identify improvement areas. The feedback is used to further fine-tune the programme in subsequent reviews to ensure continued support for the programme.

Finally, for the programme to be sustainable over the long term, consideration has to be given to the costs involved. The costs must be affordable to both the residents and the Government. Over the years, HDB constantly reviews the MUP budget and scope of works to ensure that only essential items that meet the needs of the residents are included. Non-essential items are omitted. The tight control over the improvement items under MUP not only meets the Government’s goal of fiscal prudence but also benefits the residents who co-pay the upgrading costs. It also stretches every dollar of the upgrading budget, so that as many residents as possible can benefit from the programme.

SELECTIVE EN BLOC REDEVELOPMENT SCHEME

The Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS) was introduced in 1995, as part of the Government’s plan to rejuvenate and intensify development in older estates. Precincts selected for SERS are those where there are clear economic benefits to the city-state. This is assessed by considering the redevelopment potential of the site, taking into account the cost of acquisition and reconstruction, as well as other related costs. Up until March this year, 71 precincts involving some 32,700 sold flats in various old estates have been announced for SERS.

As SERS serves the national strategic objective while optimising land use, the flats identified for redevelopment under SERS are compulsorily acquired under the Land Acquisition Act. The older flats are demolished to make way for new developments after residents from these older flats are resettled into replacement flats (Figure 2). The implementation of SERS is handled with sensitivity because of the resettlement of residents. It has been found that this sensitivity during implementation helped to achieve positive ground support for the programme. HDB surveys showed that most of the affected residents appreciated the programme. Support for SERS increased further after residents moved into their new flats. A majority reported being highly satisfied with their new homes and surroundings.

FIGURE 2. EXAMPLE OF THE SELECTIVE EN BLOC REDEVELOPMENT SCHEME

Since residents are uprooted under SERS, care is taken to minimise the inconvenience caused and also to share with them the benefits of SERS. A generous benefits package for affected flat owners helps secure better buy-in. Owners are offered compensation for their existing flats based on the full market value of their flats and an assured replacement flat at affordable prices. They only need to move out of their existing flats after the construction of replacement flats has been completed. By trading their old flats with shorter leases for new ones with fresh 99-year leases, SERS residents get to enjoy new flats with the latest designs and amenities and at enhanced market values.

Understanding residents’ needs and convincing them of the benefi ts of the redevelopment scheme are key to gaining their commitment and confi dence.

In many countries, relocation is often met with apprehension and resistance from affected residents because of the uprooting and break-up of existing community ties. Cognisant of such fears, HDB has taken due measures in the planning for SERS to ensure that residents can continue living in familiar neighbourhoods with minimal disruptions to their daily routines. HDB builds a wide range of new replacement flats at nearby sites to re-house the affected residents. Through joint selection exercises, neighbours get to choose flats where they can continue to live close to one another in the new precincts. The assured allocation of new replacement flats within close proximity of their existing flats and neighbours preserves the existing community ties.

HDB also builds more new flats than required for the re-housing of SERS flat owners in replacement precincts. The surplus new flats are then sold to other applicants, with priority given to young married couples. This helps to bring in younger residents to improve the demographic and socio-economic profile of the residents in the new precincts. To encourage married children to take care of their aged parents, applicants from outside SERS precincts who apply to stay with or near their parents in replacement precincts are offered additional priority in the allocation of flats under a “Married Child Priority Scheme”. This further helps to attract young married couples to move back to the old estates to live near their parents, helping to strengthen family ties. Hence, besides the quantifiable gains from intensified redevelopment of the cleared sites, SERS helps to enhance both the physical and social fabric of older estates.

At the launch of SERS, the affected residents are consulted on the types of flats they want, the precinct name and the location and type of common facilities they wish to have at their replacement precincts. Feedback from SERS residents shows that they found the consultation exercises to be useful and effective in promoting community bonding and instilling a greater sense of ownership of the new precinct.

Overall, SERS presents a win-win solution for all the parties involved. For the city-state, SERS enables valuable land in prime areas to be redeveloped for optimal land use. For the community at large, older estates are given new leases of life through the modernisation of the physical environment and the injection of younger residents. As for the affected residents, they get to move into brand new flats with fresh 99-year leases and in better living environments without having to move away from their familiar surroundings and neighbours.

The main challenge in implementing SERS lies in gaining residents’ acceptance and support. Understanding their needs and convincing them of the benefits of the scheme are key to gaining their commitment and confidence. Hence, before any SERS project is announced, HDB carries out detailed studies of the residents’ profile, and structures the benefits packages and replacement housing to best meet their needs. Besides generous benefits packages, a comprehensive communications plan is critical in rallying residents to accept SERS. At the launch of every SERS, an exhibition is held to explain to residents what the scheme entails. HDB officers also conduct house-to-house visits to explain and provide financial counselling on the various re-housing options, and to address other concerns. Some residents, especially the elderly and less literate, will need more “hand-holding” during the implementation phase. Such personal interactions allow residents to give feedback on their individual concerns and ensure that residents are able to fully understand the basics of SERS.

A BLUEPRINT FOR RENEWAL AND REMAKING

Going forward, while upgrading and redevelopment will continue to be a part of HDB’s estate renewal strategy, they will take on different emphases. For example, lift upgrading will be accelerated to prepare for a rapidly ageing population. The MUP will be replaced by a new programme called Home Improvement Programme (HIP). Unlike the MUP which offers only the Standard Package and space-adding options, the HIP is more affordable and flexible as it allows residents of flats that have not undergone MUP to choose the improvement works they want in their flats and co-pay only for those items. Residents will also be called upon to decide on the type of facilities to be provided in their precinct through a Neighbourhood Renewal Programme (NRP). With emphasis on resident engagement, NRP’s consultative approach will help create a stronger sense of community ownership over the precinct and facilities. Similar to MUP, the HIP and NRP will be collectively decided by the residents and will proceed only if at least 75% of the flat owners in the block and neighbourhood respectively vote for the programme.

Beyond the upgrading/redevelopment of individual housing precincts, HDB has also drawn up a blueprint to renew and remake the HDB heartland. Under the blueprint, Singapore’s public housing estates will be totally transformed over the next 20 to 30 years. Different development strategies will be adopted for each category of estates. New estates like Punggol2 will have more attractive housing forms such as waterfront housing, and the full slate of commercial and recreational facilities, to realise the vision of “A Waterfront Town of the 21st Century”. For middle-aged estates like Yishun,3 where redevelopment potential is relatively lower as they were built at higher densities than the older towns, the key thrust is rejuvenation through the enhancement of facilities, the environment and flats. Hence, more recreational facilities will be added, and the housing precincts will be rejuvenated under the new HIP/NRP.

For old estates like Dawson4 where large tracts of vacant land are now available through earlier clearance programmes, a new generation of public housing with exciting design concepts like “Housing in a Park” (Figure 3) and Sky Gardens5 will be introduced. Singaporeans can therefore look forward to living in even more vibrant and sustainable communities in the coming years.

FIGURE 3. NEW GENERATION PUBLIC HOUSING IN DAWSON ESTATE: HOUSING IN A PARK

NOTES

- The Central Provident Fund is Singapore’s social security savings plan for working Singaporeans.

- Punggol town, where development started in 1998, is one of the youngest HDB towns. Located in the northeastern region of Singapore, it is bounded by water bodies on three fronts—the north, west and east.

- Yishun falls under the category of middle-aged towns that were largely developed in the 1980s.

- Dawson estate is located in the central region and where development started as early as the 1950s.

- The concept of “Housing in a Park” sets public housing within a scenic park-like environment, where residents can enjoy lush greenery close to home. It complements Singapore’s vision of “City in a Garden”. The provision of Sky Gardens enables residents to enjoy greenery at mid-level of residential blocks, and helps to soften the urban built environment.