Cities, Culture and Happiness

World Cities Summit Issue, June 2008

CITIES AND CULTURE

Cultural activities have always been closely related to urban living. While some manifestations of culture, such as churches or palaces, can be found in rural areas in abundance, most cultural activities have been undertaken in cities, often in the largest cities of the times. They are seen as loci of cultural diversity and inter-culturality, and therefore of cultural creativity. The concentration of culture in urban areas applies to culture understood in a broad and also in a more narrow sense. This concentration has been supported by the great increase in megacities (defined as those with a population of more than 10 million people), of which there were only two (London and New York) in 1950, while in 1994 there were already 22 such cities (of which 16 were in less developed regions). In 1950, about 30% of the world population lived in urban areas; this share is expected to rise to 60% in 2025.1

Culture in the broad sense can be defined in many different ways. It may, for example, be understood to mean an “expansion of human capabilities and choice” as defined in the UNESCO World Culture Report,2 or as a “common value system, viewpoints, conventions, rules, ways of life and practices of a certain group of people…”.3 Cities provide an intensive communication network for the meeting of minds; enable easy access to new technologies and the news media; and support creativity by facilitating the interaction of people with different cultural backgrounds and ethnicities.

Culture can also be understood in a narrower sense, namely as cultural industries comprising entertainment, the media, radio, TV, printing and publishing, design and advertising. This essay focuses on an even narrower, but generally used, definition of culture as art comprising the performing arts (theatre, opera, ballet) and the visual arts (painting, sculpture, music and the like).4-15 It seems that the relationship between cities and the arts has been somewhat neglected in scholarly research.16

A striking economic aspect of the performing arts is the economies of scale in production and consumption. In order for a ballet or opera house to be profitable, they require large audiences that are found in large cities. The larger the audience, the lower the total average costs per visitor. In other art forms such as painting or design, the economies of agglomeration consist more in the economies of scope which large cities make possible. The cross-fertilisation of ideas and the creativity produced find its most fertile ground in large numbers of people with different views, interests and backgrounds.

In view of these considerations, it is not surprising that the most important opera houses are found in major cities, often the capital city or the largest city in a country, such as in Paris (Opéra de la Bastille), Vienna (Staatsoper), London (Covent Garden), Milan (La Scala), New York (Metropolitan Opera) or Chicago (The Lyric). The same can be observed for the theatre and ballet.

Painters, sculptors and writers can work in isolated rural areas. Think of Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Glenn Gould, John Hughes, Thomas Pynchon or J. D. Salinger. However, it should be noted that they often decide to do that only later in life, after having found their individual style, and after having established themselves in the art community which is based in cities. Important art movements such as impressionism and expressionism have evolved in Paris, and more recent ones emerged in New York.

Museums and art galleries are certainly possible in rural areas but the advantages of agglomeration are nevertheless strong as the most important museums are located in major cities, for example, the Prado in Madrid, the Louvre in Paris, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the National Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum in New York or the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Cities provide an intensive communication network for the meeting of minds; enable easy access to new technologies and the news media; and support creativity by facilitating the interaction of people with different cultural backgrounds and ethnicities.

For similar reasons, the traditional and the modern media as adduced above also tend to be concentrated in large cities. A study by Stefan Krätke on “Global Media Cities in a Worldwide Urban Network”3 analyses the distribution of 33 global media firms with 2,766 enterprise units. The most important media cities in the world turn out to be New York, London, Paris, Los Angeles, Munich, Berlin and Amsterdam; each of these cities is host to between 64 and 185 enterprise units and between 18 and 29 global firms. This set of major “Global Media Cities” is similar to the major cities with respect to the performing arts and museums.

This close connection between cities and culture, the arts more narrowly, has also been made evident by an initiative in the European Union to name each year a “European City of Culture” which, interestingly enough, since 1999 has been renamed “European Capital of Culture”. This was initiated in 1985 and has since received huge prominence. The first cities to carry the title were Athens (1985), Florence (1986), Amsterdam (1987), West Berlin (1988) and Paris (1989). In the year 2000, no less than nine cities were named “European Capitals of Culture”—Reykjavik, Bergen, Helsinki, Brussels, Prague, Krakow, Santiago de Compostela, Avignon and Bologna. This same idea has been taken up in other continents. There are now programmes naming “American Capitals of Culture” as well as “Arab Cultural Capitals”. Obviously, the choices made in Europe and elsewhere have only partially been based on artistic merit; of great importance is a politically “fair” distribution over space and countries. What matters in our context is that this programme identifies cities and capitals, with culture as a fundamental consideration.

HAPPINESS AND CULTURE

For many people, consuming art obviously provides a highly satisfactory experience. This opinion is supported by the enormous number of people who visit museums and, above all, special exhibitions, and attend the thousands of festivals that are held all over the world. It has to be remembered that nobody is “forced” to visit such a cultural site (except perhaps school children). Rather, people do it willingly and expect to receive some pleasure from such an activity.

Individuals, who consider themselves happy, laugh more, have fewer problems and absences from their workplace, are more sociable and more optimistic.

Modern social science can help us to shed light on the relationship between happiness and the arts due to advances in survey research and statistical estimation techniques. In particular, it is possible to answer the question to what extent people derive satisfaction from artistic activities. Over the last few years, it has become possible to capture the subjective well-being of persons in a satisfactory way.17-20 One of the ways is through large scale surveys. In the following, the German Socio-Economic Panel, generally considered to be the best data source in the world, was used. It is based on surveying 22,000 comparable persons for their entire lives yielding 125,000 observations. These proceedings allowed changes in life circumstances and preferences of particular persons to be captured over time. To answer the question if and to what extent “art makes people happy”, two survey responses must be combined. It must measure how happy people consider themselves while establishing, at the same time, how often they attend cultural activities.

The survey question with respect to happiness is: “Overall, are you satisfied with the life you lead?” The answer to this question captures a long-term and deep-seated evaluation of one’s well-being, which in scientific terminology is called “subjective, self-reported life satisfaction”.21 It thus differs from a short-term affect. Those indicating “0” on the scale ranging from 0 to 10 consider themselves “deeply unhappy”, while those indicating “10” are “extremely happy”. Most persons are quite satisfied with the life they lead; the average person chooses values between 6 and 8. The subjective life satisfaction indicated by the respondents corresponds well to objective observations. Individuals, who consider themselves happy, laugh more, have fewer problems and absences from their workplace, are more sociable and more optimistic, and are less prone to attempt suicide.

The next question captures attendance at cultural activities: “How often do you attend cultural activities such as concerts or theatre performances during your leisure time?” It was found that almost half the respondents (45%) “never” attended any cultural activity. Thus, the consumption of culture thus does not seem to be very popular in Germany, a country proud to be considered a “nation of culture”. This impression is strengthened when taking into account that 44% of the respondents stated that they attend a cultural event “less than once a month”. Hence, almost 9 out of 10 Germans have little, if any, active contact with cultural activities. 15% of respondents stated that they visit a cultural occasion “once a month” and a minute 1% stated that they do so “weekly”. These figures may well be an over-estimation, as at least some of the respondents tend to state that they attend more cultural events than they actually do so as not to look “uncultured”. These figures indicate that “culture” in the sense of attending artistic activities takes place in an isolated sphere away from the interests of the large majority of the population. Great efforts are needed to change this picture.

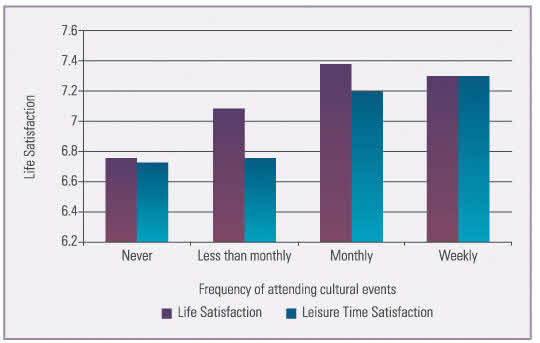

Figure 1 shows the results of the surveys on life satisfaction and cultural attendance. Persons who attend cultural events often are more satisfied with the life they lead than those who consume art rarely or never. The positive correlation between happiness and cultural consumption is marked. Those who “never” attended any artistic manifestation have a self-reported life satisfaction of 6.7 (on a scale from 0 to 10). In contrast, those who had attended a cultural event “weekly” reveal a happiness level of 7.3, and therefore indicated that they are much more satisfied with the life they lead.

FIGURE 1. ATTENDANCE FREQUENCY OF CULTURAL EVENTS AND LIFE SATISFACTION, GERMANY 1985–1999 (SOURCE: COMPILED FROM RESEARCH FINDINGS OF THE GERMAN SOCIAL ECONOMIC PANEL)

Figure 1 also shows the relationship between artistic consumption and satisfaction with leisure (instead of, as before, with life as a whole). There is again a marked positive correlation between the two. Those who are culturally active consumers are also those more satisfied with how they spend their leisure time.

DOES CULTURE MAKE PEOPLE HAPPY OR DO HAPPY PERSONS ATTEND MORE CULTURAL EVENTS?

It might be argued that the positive relationship revealed in Figure 1 is due to quite different factors. It could, for instance, be claimed that persons with higher income are happier and attend more cultural activities because they can more easily afford to do so. Both statements are indeed in line with the results of scientific research. Persons with higher income more often report that they are happy than those with lower income. At the same time, it is well-known that mostly persons with above average income visit artistic events. The argument raised must therefore be taken seriously.

A more thorough analysis considers the relationship between artistic consumption and happiness using advanced statistical (or econometric) methods, in particular multiple, simultaneous regression estimates. The empirical results confirm that art is mostly consumed by persons with above average incomes. Even with this fact taken into account, the relationship graphically shown in Figure 1 is supported: the more artistic events people attend, the more satisfied they are with their lives.

This positive relationship between happiness and culture is good news for the cultural sector and the cultural industries. However, the causal direction remains open. Does attending more cultural events raise life satisfaction, or is the opposite true, namely, are happy people more likely to attend cultural events? So far, scientific research has not been able to answer this question decisively, mostly because the data available are of insufficient quality. Nevertheless, various aspects strongly suggest both causal directions being relevant. Happier persons are cognitively more open, more inquisitive and socially more active, resulting in more visits to cultural venues catering to these preferences. At the same time, it is obvious that art can contribute to an individual’s well-being. However, the effect does not necessarily apply to the same extent to all types of art. An individual who attends a deeply pessimistic theatrical play, or visits a museum that shows depressing or even distressing paintings is unlikely to become happier. On the other hand, a beautiful play or an attractive show of paintings is likely to raise people’s well-being.

POLICY CONCLUSIONS

The empirical results have been produced with the help of data from Germany. The situation may be different in other countries. This is certainly true and must be left to future research. On the basis of what is known today, it may, nevertheless, be proposed carefully that similar relationships pertain to different countries and regions of the world: persons with higher income exert a higher demand for culture than do people with low income and, at the same time, people consuming culture tend to be more satisfied with the life they lead.

Countries experiencing successful economic development should take into account that their population will exert an increasing demand for cultural activities in the future. The decisive question is in what way culture should be encouraged by policy.

These insights are of immediate relevance for policy. Countries experiencing successful economic development should take into account that their population will exert an increasing demand for cultural activities in the future. The decisive question is in what way culture should be encouraged by policy. As has been discussed extensively in the Economics of Art, there are many different ways for the government to support the arts. If the state supports the arts through direct subsidies, it makes a decision at the same time about what kind of art is supported. This would, for example, be the case if the government subsidises or fully finances the establishment of an opera house. In such a case, only this particular form of art benefits. Art can also be supported by granting tax reductions to patrons of the arts. In that case, the preferences of the individual supporter, rather than those of the government, are decisive. For example, a wealthy person donates $10 million to establish a museum for impressionist art. Assuming a marginal tax rate of 60%, the donation would cost 40% or $4 million, but the donor can nevertheless impose his/her preferences on the museum and benefit from the social recognition that comes with having a museum named after oneself. While the loss of tax income to the state of $6 million must be borne by the population as a whole (since the money cannot be used for other purposes), it has no say with regard to the funds that are going to the museum. Strict regulations concerning tax deductibility can change this outcome, but has the disadvantage of an unfortunate bureaucratic interference.

A visionary alternative to direct subsidies or tax reductions would be the establishment of a system of culture vouchers. The recipients of these vouchers could be anyone, for example, every resident of a country or all taxpayers; the total value of these vouchers could be freely determined. The recipients could use the voucher as if it were cash to pay for access to art institutions the government deems worthy and puts on a corresponding list. The venues can then cash the vouchers they received at the treasury. As a consequence, the suppliers of cultural services would have a strong interest to offer art experiences the population appreciates; in addition, they would be induced to advertise their services in an attractive way. In contrast to what many people believe, culture vouchers do not necessarily induce suppliers of art to cater to the masses, that is, to produce “popular” art, only. They can also offer art forms appreciated by only a minority that is prepared to spend a large part of their vouchers on these products. One of the strong points of a voucher system is that the recipients of vouchers have a strong incentive to use the vouchers and to attend cultural events rather than to let them go to waste. They serve as a welcome means to bring the substantial share of people who admit to “never” or “rarely” attending cultural events to start engaging in it. Even if culture vouchers are passed on, culture is associated with value. This establishes a beneficial link between the “culture-absent” part of the population and the arts.

The various ways of supporting the arts differ with respect to how they take into account the increasing demand for artistic events. Culture vouchers reflect most strongly the preferences of the population, while tax reductions do this for a particular group of people, in general high-income recipients who, due to their higher marginal tax rates, profit the most. Direct subsidies shift the decision about what form of art is to be supported to politicians and public officials. The various forms of public support can well be combined, especially for art forms requiring high set-up costs—for instance, opera houses or museums; a part of the total subsidies can be given ex ante by a direct subsidy to mitigate the initial financing problems and to provide more planning security for the administrators of the cultural venues.

The finding that the consumption of art raises happiness also has policy implications. It adds a novel answer to the question of why government should support culture. Up to now, the literature on the Economics of Art argued that the existence of positive externalities, in the form of education, existence, option and bequeath values,8 legitimises government intervention. Happiness research points to an additional reason, namely, that attending cultural events increases people’s life satisfaction. The consumption of culture is, to a considerable degree, an experienced good, i.e., many persons appreciate the good only after they have consumed it. People are insufficiently aware, and perhaps some not at all, that culture is a source of happiness.22 This fact legitimises the support of the arts for a restricted period of time, until those induced to visit cultural events have become fully aware of the positive effect on their subjective well-being.

This essay demonstrates that cities, culture and happiness are closely intertwined. It also suggests direct consequences worth considering as an important element of a visionary public policy.

NOTES

- Jelin, Elizabeth, “Cities, Culture and Globalization,” in World Culture Report. Culture, Creativity and Markets (Paris: UNESCO, 1998), pp105-24.

- McKinley, Terry, “Measuring the Contribution of Culture to Human Well-Being: Indicators of Development”, in World Culture Report. Culture, Creativity and Markets (Paris: UNESCO, 1998), pp322-32.

- Krätke, Stefan, “Global Media Cities in a Worldwide Urban Network”, European Planning Studies 11 (2003): 605-28.

- This has been the object of the interdisciplinary field of the “Economics of Art” which by now is well established. See monographs in Notes 5 to 10, and the collections of articles in Notes 11 to 15.

- Baumol, William J. and William G. Bowen, Performing Arts—The Economic Dilemma (Cambridge, MA: Twentieth Century Fund, 1966).

- Peacock, Alan T., Paying the Piper. Culture, Music and Money (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993).

- Benhamou, Françoise, L’économie de la culture (Paris: La Découverte, 2000).

- Throsby, David, Economics and Culture (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- Frey, Bruno S. and Werner W. Pommerehne, Muses and Markets: Explorations in the Economics of the Arts (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989).

- Frey, Bruno S., Arts & Economics. Analysis & Cultural Policy, 2nd ed (Berlin, Heidelberg; New York: Springer, 2004).

- Peacock, Alan T. ed., Does the Past have a Future?: The Political Economy of Heritage (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1998).

- Rizzo, Ilde and Ruth Towse, The Political Economy of the Heritage: a Case Study of Sicily (Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2002).

- Ginsburgh, Victor A. and David Throsby, eds., Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 2006).

- Towse, Ruth, ed., A Handbook of Cultural Economics (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003).

- Hutter, Michael and David Throsby, eds., Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics and the Arts (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- See example in Krätke (Note 3, p 605): “What has mostly been overlooked (in the literature on cities and culture, BSF), however, is the fact that cities are also places where goods and services are produced for a local and supra-regional cultural market”.

- Frey, Bruno S. and Alois Stutzer, Happiness and Economics: How the economy and institutions affect human well-being (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

- Layard, Richard, Happiness: Lessons from a New Science (New York: Penguin, 2005).

- Bruni, Luigino and Pier Luigi Porta, eds., Economics & Happiness. Framing the analysis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Frey, Bruno S., Happiness: A Revolution in Economics (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2008).

- For simplicity, and in line with the literature, the terms “happiness” and “life satisfaction” are used interchangeably in this paper. However, the reference always corresponds to the longer term and deeper feeling of subjective well-being rather than a short-term affect.

- Stutzer, Alois and Bruno S. Frey, “What Happiness Research Can Tell Us about Self-Control and Utility Misprediction”, in Frey, Bruno S. and Alois Stutzer, eds., Economics and Psychology (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2007): pp169-95.