Achieving Sustainable Urban Development

World Cities Summit Issue, June 2008

The issue of sustainable development has taken centrestage in recent years. Government agencies, non-governmental organisations and private companies alike are busy drawing up plans and promises for greater sustainability. In 2004, the Mayor of London announced "The London Plan", which sets out a framework of policies to accommodate London's growth in a sustainable way.1 In 2007, it was New York City's turn to unveil its comprehensive plan, "PlaNYC", which pledged to remake New York into a more sustainable metropolis.2 In particular, the potential impact of global warming has captured the world's attention.

Today, much of the public debate on sustainability centres on reducing carbon emissions and mitigating the effects of climate change. There is much emphasis on using green technology to help reduce energy usage and keep our air and water clean.

Indeed, technology is important and will continue to be a key enabler to solve many of the technical challenges associated with sustainable development. However, what may be less visible and less appreciated is the fact that sustainability can be attained only when we take a holistic and comprehensive approach. This starts with making strategic planning choices that cascades to the formulation of innovative policies, and subsequently implementing technologies to tackle urban and environmental problems. At the top end of the continuum, sustainable development involves generating economic growth and societal well-being without exhausting our limited natural resources. Keeping every tree and shrub in Singapore untouched does not constitute sustainable planning. Neither does building as many petro-chemical plants as we can qualify as sustainable, even if this creates jobs and income for our people. Sustainable development requires a careful balancing of different demands and differing priorities. Within this broad planning framework, we develop good policies and tap on technology to find the best ways to deal with issues on protecting the environment, climate change, clean energy use, and effective waste and water management.

Singapore has recognised the need for such a comprehensive approach. Since our Independence,3 we have taken on the challenges of providing for a nation in a city-state environment with virtually no natural resources. Today, ensuring sustainable development in Singapore has taken on greater impetus with the formation of an Inter- Ministerial Committee on Sustainable Development (IMCSD), chaired by Ministers of both the Ministry of National Development (MND) and the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR). The IMCSD looks at sustainability from both a national development and an environmental perspective. An Inter-Ministerial Committee on Climate Change will also study what Singapore can do to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change.

THE TRADE-OFFS

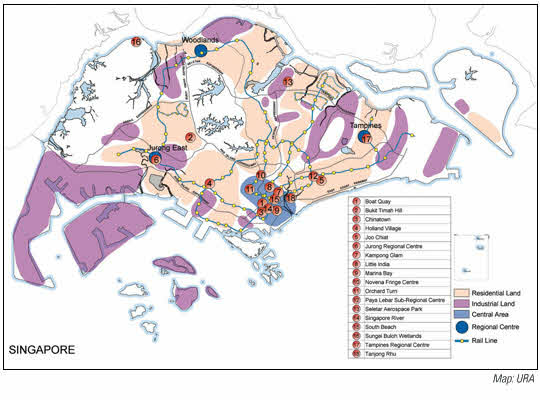

Planning for sustainable urban growth within Singapore's borders is the priority of the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). In fact, it is crucial for the country's survival. A city-state without hinterland, we face the challenge of ensuring we have sufficient land for housing, recreation and business. At the same time, we have to set aside land for defence, power generation, waste disposal and water catchment-all within 700 square kilometres of land. With one of the largest container ports in the world, our sea-space is limited by our international boundaries. As a regional air hub and with five airports and airbases, building skywards is also constrained. Deciding on one land use over a myriad of other possibilities inevitably involves making trade-offs. For example, having more parks and open spaces means that more of us will live in high-rise housing. Allocating more land for industries could mean loss of waterfront and heritage areas. Having more roads and a smoother drive to work may result in smoggier air and more noise pollution.

As URA's decisions affect many people, we cannot afford to go it alone. We have to make these evaluations and trade-offs together with our partner agencies like the Land Transport Authority, the National Parks Board, the Housing and Development Board, the Public Utilities Board (PUB), the National Environment Agency, economic agencies as well as various other stakeholders. The result of many hours of discussions and consultations are consolidated into our long- and medium-term land use plans. One product of many such debates and decisions is the Master Plan 2008 which was unveiled to the public in May 2008. This Plan guides Singapore's development over the next 10 to 15 years in a sustainable manner.

These land use plans cater to multiple needs. For example, they try to facilitate economic growth by providing more industrial land for petro-chemical and aeronautical industries, hotel and tourism projects, as well as an expanding financial sector. These are then balanced with social considerations for achieving a high quality living environment to meet rising aspirations. We will provide more variety of good quality housing, more greenery and more leisure choices.

The challenge is to fit it all in. Planners overcome our land constraints by developing innovative solutions. We work towards ensuring that business activities use land optimally. For example, factories built with ramps allow trucks to access every floor, hence they function effectively as flatted factories. Where possible, facilities such as polyclinics, libraries and community centres are co-located to maximise land space. Additional structural loading is also provided over Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) stations and underground roads so that we can build above them. To create a greater sense of space, our major parks and coasts are linked up using park connectors.4 Cycling and jogging routes will increase more than four-fold from 100 to 400 kilometres eventually. We also provide incentives for developers to develop more vertical greenery like skyrise gardens5 to mitigate the dense built-up space. In addition, we work closely with PUB to utilise canals and inland reservoirs to create beautifully landscaped "lakes and streams" that integrate with developments. As a result, more leisure space is created, built-up areas are "softened", and we have been able to increase real estate values.

Various agencies also work together to harness new technologies to optimise the use of land. For example, the development of the Deep Tunnel Sewerage System by PUB replaces the existing six water reclamation plants and about 130 pumping stations. This frees up approximately 1,000 hectares of land occupied by the existing facilities and buffer zones around the plants. Incinerating and recycling our wastes reduce the need for waste disposal sites. The JTC Corporation6 is piloting a project to use subterranean rock caverns for storage. All these initiatives work towards making the most of what we have.

CENTRAL PLANNING OR ORGANIC GROWTH?

A common question is "Should the Government leave things more organic and unplanned, or should it play an active role in shaping the urban landscape?"

Supporters of a more market-led approach often argue that top-down, government-led planning is overly rigid; centralised planning cannot create places with sufficient character, identity and vibrancy. They see unplanned growth and a more laissez-faire approach to urban planning as the preferred alternative.

On the other hand, unplanned growth, especially in fast growing and densely populated Asian cities, can lead to disastrous consequences. Market fluctuations can be very rapid, and private sector short-term responses may have very long-term repercussions. Once an office tower or factory is built, it is difficult, if not impossible, to "undo" the development. We cannot just walk away from mistakes made in our existing city and plan a new city. There is simply no room to do so. Furthermore, the market cannot ensure that infrastructure keeps pace with development. We have to make sure that our city works. It must accommodate a high population density while minimising the usual urban problems.

A responsible government that is far-sighted must have the ability and capacity to make decisions that may not necessarily pay off in the short term but will reap benefit in the longer term. For example, setting up MRT transport networks require high upfront costs that the private sector often shies away from. Sustainable development ultimately means keeping an eye on our future.

As a planning agency, URA makes strategic decisions with years ahead in mind. The Concept Plan is a strategic, long-term land use and transportation plan to guide Singapore's development for 40 to 50 years. In the 1991 Concept Plan review, it became clear that we would face the potential problem of massive traffic congestion in and around the Central Business District (CBD) during peak hours. To tackle this problem before it came to a head, a long-term strategy to decentralise commercial activities to commercial centres outside the central area was adopted.

By distributing commercial activities throughout the island and bringing jobs closer to homes, travel into the central area would be reduced, and so would both peak-hour congestion as well as vehicular emissions. Decentralisation would also offer businesses alternative and more affordable office locations. This decision could only come about through top-down planning (see box story on "Why Jurong?"). Conversely, left on its own, the market would likely continue to develop and expand the CBD-an unsustainable plan for the long term.

Another key consideration in our planning is to provide crucial facilities and amenities that will improve the quality of living, but which through normal market forces, would not be provided by the private sector. Would the private sector build parks, park connectors and community facilities instead of alternative, higher value uses? Similarly, who will ensure that there will be a buffer shielding our homes from industrial developments, or sheltered walkways and universally accessible public facilities? The role of URA as a central agency ensures that the liveability of Singapore will not be left to chance. Through comprehensive planning, residents can still trek through the Sungei Buloh Wetlands or climb Bukit Timah Hill to enjoy the sunset.

Planning also creates business opportunities and protects real estate values. Through the planners’ vision, new opportunities are created for the private sector to invest and to creatively transform dilapidated areas or virgin land into highly valuable assets. The Government supports the private sector with timely land release and infrastructure. Today, the Singapore River, Tanjong Rhu and Marina Bay (Figure 1) areas are examples of this successful public-private sector collaboration. Transparent plans and orderly development also give certainty and protect the value of homes and business investments.

FIGURE 1. AN IMPRESSION OF THE MARINA BAY WATERFRONT

WHY JURONG?

FIGURE 2. AN IMPRESSION OF JURONG LAKE DISTRICT IN THE FUTURE

To mitigate congestion within the city area and to bring jobs closer to homes, URA proposed a strategy to develop more commercial centres outside of the central area. We had identified several locations that were strategically well-spread throughout the island and well-served by MRT stations. Of these locations, the Tampines Regional Centre in the eastern part of the island and the Novena Fringe Centre nearer the city have already been developed into successful office clusters supported by retail, food and beverage (F&B), and entertainment amenities. As part of the next phase of this development strategy, plans are being rolled out for Paya Lebar sub-regional centre (located between Tampines and the city centre) and the Jurong Regional Centre (a commercial hub around the Jurong East MRT station on the western part of the island).

Some may ask: Why Jurong? To many people, the Jurong of today is a sub-urban residential area located far away from the city centre. It is also perceived as an industrial area.

Most businesses would likely prefer to continue to expand within the established office hubs in Tampines and Novena as they are better established and more familiar with these areas. However, the planners took a longer term view, that there is a need to establish a large commercial centre to serve the western region. They recognised that Jurong had a huge untapped potential.

Jurong is located within the heart of a population of 1 million residents. It has ready access to a large talent and labour pool. It is central to an established cluster of multinational and global businesses, ranging from the high-technology sector around the International Business Park to biotechnology, pharmaceutical and chemical industries in Jurong and Tuas. Hence, there are vast opportunities for business and commercial services to serve these companies. Jurong is also a major transportation hub. It is well-connected to the city and the rest of Singapore by rail and expressways.

Creating a major commercial centre would also help create extra buzz in the western part of Singapore. Jurong will be transformed into a vibrant hub with an eclectic mix of office, retail, residential, hotel, entertainment, F&B and other complementary uses. However, Jurong will not be a duplicate of Tampines Regional Centre or Novena. Its proximity to the beautiful Jurong Lake presents a huge opportunity to transform Jurong into a unique lakeside destination for both business and recreation. Lakeside, which is located near to Jurong, is envisaged to be a key leisure destination for families and visitors, with exciting attractions as well as a mix of complementary retail, F&B, hotel and other lifestyle developments. This will make the Jurong area appealing, attractive and exciting for residents, workers and visitors.

REDEVELOPMENT OR CONSERVATION?

Another dilemma in planning is deciding between developing or retaining buildings and areas. Safeguarding our built and natural heritage is undeniably important. Physical reminders of our past help tie our people to the country and, at the same time, create a varied and appealing urban landscape. Similarly, protecting areas rich in flora and fauna is critical to ecologically sustainable growth. Today, we have a well-established programme to conserve Singapore’s historically and architecturally significant buildings, as well as legislation and programmes to protect our nature areas from commercial development.

However, conservation of our built heritage and nature areas comes at a price—the opportunity cost being the higher value alternative use that such land can be put to. A careful balance has to be struck.

The conservation of buildings found in the historical districts of Chinatown, Kampong Glam, Little India and Boat Quay are good case studies. These districts are all located within the Central Area, and occupy prime land that can potentially be redeveloped into Grade A offices or hotels. As our economy expands, so does the demand for prime land. Nevertheless, a deliberate decision was made to safeguard these areas because of their tremendous architectural, historical and social significance. At the same time, we took the pragmatic decision to allow conserved buildings to be adapted for modern-day and higher value uses such as offices, shops and hotels, whilst retaining the spirit of the building’s original design. Such an approach helps to ensure that old buildings do not become just hollow historical relics, but remain economically viable and relevant. Another way in which we safeguard the twin objectives of heritage and value preservation is to allow for “old and new” development combinations in selected areas. Where appropriate, we have kept parts of the old buildings fronting the street, thus preserving the streetscape and sense of scale, but allow new and higher buildings at the rear.

There are times when halting development of an area is not feasible even though there is pressure to do so. When it was announced that there were plans to redevelop Seletar and its surroundings, residents and members of the public who enjoyed the lush greenery and old colonial architecture of the area were unhappy. However, developing the area into an aerospace hub would enable Singapore to capitalise on the strong growth in the global aerospace industry and create an estimated 10,000 jobs.

In order to best balance both concerns, inputs from the different stakeholders were sought and their considerations incorporated into the plans. The new Seletar Aerospace Park will now conserve a cluster of colonial bungalows, which could be used as training facilities or to provide amenities, as well as retain areas of greenery and significant biodiversity. This way, the development would cater for economic growth while retaining Seletar’s distinctive charm.

Therefore, when it comes down to deciding whether a building should be conserved or an area safeguarded from development, we try to ensure a balanced evaluation of the social, environmental and economic factors. We are glad that our efforts have been recognised. The Urban Land Institute conferred its Global Award for Excellence on URA’s Conservation Programme in 2006. This reaffirms Singapore’s conservation approach which “… has achieved a balance between free-market economics and cultural conservation”.7

MAKING CHOICES TOGETHER

While there are merits to a more centralised approach to planning, we certainly recognise that planners do not have all the answers. We need to tap on the private sector for its market knowledge and enterprise, and there must be provision for the natural evolution of places and buildings. Have we struck the right balance between planning and organic development? Some critics think not, lamenting that Singapore has become a too-clean, too-efficient urban entity that lacks the pizzazz to make it a truly great city. At the same time, others have lauded Singapore’s transformation into one of the world’s most liveable cities precisely because we offer an irresistible combination of orderliness and fun.8

To strike the right balance, we need to engage the public in our planning. When citizens are given a chance to voice their needs and concerns, the likelihood that these needs are appropriately addressed increases. Having a say in planning also creates a greater sense of ownership and responsibility within the community. Businesses are in the best position to give feedback on market needs and changing trends. The collective experiences will yield important insights that might elude a policymaker without similar intimate knowledge

of the ground. During consultation, it is natural that interest groups lobby for their specific interests. These interest groups could range from nature and conservation champions, business groups, to real estate developers and architects, as well as residents. The challenge is to weigh these comments and ideas before incorporating them into our land use plans.

The Master Plan 2008 is one example of such a consultation. Part of the Master Plan process involved the formulation of a new Leisure Plan. To develop the Leisure Plan, focus group discussions were held with leisure business providers, group representing the interests of the aged, handicapped, nature-lovers, sports enthusiasts, as well as local stakeholders. An interesting outcome of putting everyone together was that the different interest groups had a chance to hear occasional opposing viewpoints from one another. URA then incorporated the focus groups’ inputs into the Leisure Plan, balancing the needs of the various stakeholders.

We listen to both accolades and criticisms, and continue to tweak the equation by offering the market more flexibility where possible. For example, URA has introduced more flexible “white” zoning, which allows all uses except pollutive ones. Developers can decide on different combinations of residential, commercial or recreational uses based on their own market outlook (see box story on “Working with the Private Sector”). We have also taken a more “hands-off” approach for selected areas of Singapore like Holland Village and Joo Chiat. These are neighbourhoods that have grown organically with interesting clusters of eateries and shops which Singaporeans and visitors love. We should allow these areas to continue to develop their own identity. At the same time, we will plan for the necessary infrastructure, such as car parks and utilities, to support these areas.

Regulation is practised with a “light touch”, with risk management considerations built in. This can be seen in the relaxation of rules on home offices which has enabled small businesses and consultancies to be set up within the home, resulting in reduced business costs. We have put in place mechanisms which allow the private sector to challenge existing guidelines and to put up new ideas, with their views heard by panels comprising private sector representatives. We hold regular dialogues with various stakeholders and interest groups, and remain open to new ideas and suggestions.

WORKING WITH THE PRIVATE SECTOR

South Beach and Orchard Turn are two government land sales sites that will feature prominently in Singapore’s urban landscape. The South Beach project which is located along Beach Road, a highly strategic nodal location between Marina Centre and the Civic District, will offer a mix of prime office space, luxury hotels, retail and residences. Orchard Turn, located on bustling Orchard Road, will be a luxury retail and residential development right in the heart of our prime shopping area. Given their strategic locations, it was critical to incorporate urban design guidelines into the tender conditions of these sites to ensure that the resulting developments would be attractive, and would incorporate features that meet the public’s needs.

The tender conditions for Orchard Turn require the successful company to upgrade the underground link between Orchard MRT and Wisma Atria, a private mall, to create a better pedestrian experience. In addition, the development has to include a public plaza space at the popular Orchard Road/Scotts Road junction and an art exhibition space to allow for the showcase of artworks and sculptures.

For South Beach, a “two-envelope system” was adopted to evaluate the tenders for the site. The “two-envelope system” is an approach within the tender process where price bids and concept proposals are submitted under separate envelopes and evaluated separately. The concept proposals are first evaluated, and only tenders that meet the concept criteria will be considered for award. This approach ensures that only the better designs and concepts are shortlisted, before the land is awarded based on the highest bid. Interested developers of the Beach Road site had to submit a design that provided for good pedestrian connectivity and public spaces. They also had to ensure that conservation buildings within the site would be sensitively adapted for new uses of office space, luxury hotels, retail and residences. A high bid tender submission in this instance would not have been sufficient.

In both developments, the URA’s role and objective are to engage the private sector towards achieving a high quality urban environment.

FIGURE 3. AN IMPRESSION OF ORCHARD TURN |

FIGURE 4. AN IMPRESSION OF SOUTH BEACH |

LOOKING AHEAD

Singapore’s brand of sustainable development is unique. We have already established a good foundation by institutionalising a planning process that takes a long-term view. Our comprehensive and integrated urban planning framework ensures that all development needs are considered, and the necessary trade-offs are debated and decided upon. A pragmatic approach is taken—one which recognises the need to generate economic growth yet, at the same time, safeguards social and environmental considerations in a balanced way. Planning is not done in isolation but through a consultative process with a Whole-of-Government approach and in collaboration with the private sector. We value public-private sector partnerships in developing our city. Collectively, the Government has started to pursue innovative and state-of-the-art green technologies to deal with issues of environmental protection, energy usage and urban management. All these initiatives will stand us in good stead by giving us more room to manoeuvre within our tight land constraints. We are optimistic that this comprehensive approach can work towards achieving a sustainable Singapore where we can have both economic growth and a high quality environment for all who live here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cheong Koon Hean is Chief Executive Officer of the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). She is also concurrently the Deputy Secretary (Special Duties) in the Ministry of National Development, as well as a board member of the JTC Corporation and the National Heritage Board. Mrs Cheong has held several portfolios in the URA and has extensive experience in both strategic and local planning as well as in urban design and conservation. As Chief Executive Officer of the URA, her role is to plan and facilitate the physical development of Singapore.

NOTES

- The London Plan: Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London (Consolidated with Alterations since 2004) (London, UK: Greater London Authority, 2008). https://www.london.gov.uk/

- PLANYC: A Greener, Greater New York (New York, USA: City of New York, 2007). http://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc2030/html/home/home.shtml

- Singapore became an independent nation on 9 August 1965.

- The Park Connector Network is an island-wide network of linear open spaces that link up major parks, nature sites and housing estates in Singapore. They are usually found alongside the many rivers and canals that flow through the island and are often used as convenient shortcuts to housing estates, MRT stations and schools.

- Skyrise gardens refer to gardens on rooftops and sides of high-rise buildings. Skyrise gardens help to optimise land use while improving the environment for quality living.

- JTC Corporation is one of Singapore's leading provider and developer of industrial space.

- Urban Land Institute Global Awards for Excellence: Singapore Conservation Programme. http://www.uli.org/AM/ Template.cfm?Section=Global_Awards_for_Excellence &Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=71891

- In 2008, Singapore was listed by the Hub Culture Zeitgeist Cities Ranking as one of the top 20 global vibrant cities and was also voted as the best city to live in for Asian expatriates 10 years running according human resources consultancy ECA International.