Sampan Singapore: New Lines, Nets and Capabilities in the COVID Storm

Digital Special Edition (March 2021 Update)

Singapore has often been referred to by its leaders as a “sampan” (a traditional small fishing boat), easily tossed about by the waves of global competition.1, 2 The implication is that the country is vulnerable to external shocks, and therefore needs to pull together and adapt quickly to the changing environment.

After decades of development and growing affluence, some have sought to reframe Singapore in more optimistic terms. One such view describes Singapore a “well-oiled cruise ship”3 prompting PM Lee Hsien Loong to caution that “once you think you are in a cruise ship and you are on a holiday and everything must go swimmingly well and will be attended to for you, I think you are in trouble."4

This COVID-19 storm has put paid to the notion that Singapore can afford to ignore its inherent vulnerabilities. It has highlighted the realities faced by Singapore as a small island nation: that we are scarce on resources and dependent on the rest of the world for essential goods. As a small state, Singapore continues to rely heavily on imports, which have been badly disrupted by the pandemic. To weather the COVID-19 storm, the Singapore sampan has had to tap on both old and new “fishing lines” (bilateral relations) and “fishing nets” (multilateral relations) to mitigate these effects and ensure our very survival.

Singapore has been referred to as a “sampan”, vulnerable to external shocks, which therefore needs to pull together and adapt quickly to the changing environment.

The Storm

After news of the outbreak took hold in January 2020, and widespread travel lockdowns were announced, Singapore (like many other countries) saw incidents of panic buying of food and toilet paper.5 This worsened when Malaysia—a major source of our vegetable, chicken, egg imports, and the main manufacturer for many of the essential goods used in Singapore—implemented a Movement Control Order on 18 March 2020.

Although both the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) and political leaders assured the public that Singapore was not short on essential food or household items, some Singaporeans still feared that the Malaysian lockdown would cut off Singapore’s main “fishing line”: our bilateral trade link with Malaysia.

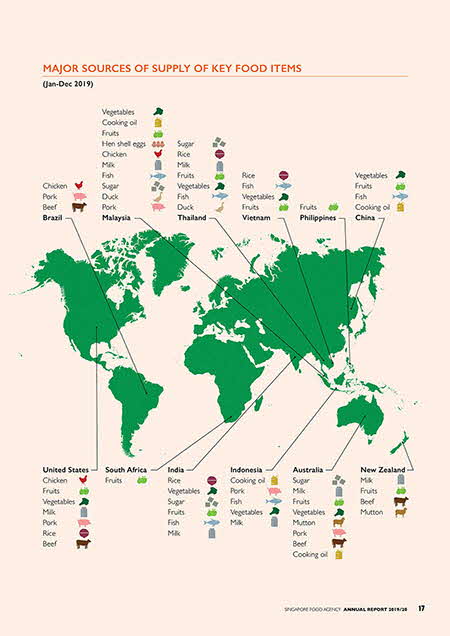

Figure 1. Singapore’s Major Sources of Supply of Key Food Items

Source: Singapore Food Agency 6

Figure 2. Empty shelves at Fairprice outlet at White Sands in Pasir Ris, 7 February 2020.

Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited.

Permission required for reproduction. 7

Figure 3. A queue forms outside FairPrice Finest at Clementi Mall, 10 April 2020.

Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited.

Permission required for reproduction. 8

In fact, Singaporean planners have long been mindful of our exposure to supply shocks. As a nation, we have taken measures to secure and tap on a variety of “fishing lines” and “fishing nets” in order to minimise trade disruptions and keep our sampan afloat even in a time of crisis.

COVID-19 has highlighted the realities faced by Singapore: that we are scarce on resources and dependent on the rest of the world for essential goods.

Fishing Lines

When Malaysia announced its decision to lock down and bar travel, Singapore’s immediate response was to work out an arrangement to have continued movement of cargo between both countries. With Malaysia supplying 37% of chicken and 15% of fish consumed in Singapore, as well as a large proportion of eggs, vegetables and milk, such arrangements were critical to assuage concerns that Singapore’s food supply would not be disrupted despite the lockdown. Other essential products such as pharmaceuticals and infant diapers were also allowed through the checkpoints.9

Figure 4. Immigration and Checkpoints Authority officers inspecting items carried by a delivery truck from Malaysia, Singapore Cargo Clearance Centre at Woodlands Checkpoint, 18 March 2020.

Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited.

Permission required for reproduction. 10

Apart from securing our trade lines with Malaysia, Singapore also made effort to find other supply lines. For example, on 1 May, Singapore and Japan issued a joint statement to deepen bilateral cooperation to secure supply chains for essential goods, including agricultural food products and medical supplies.11

On 5 May, it was reported that China had contributed 500,000 surgical masks and 100,000 KN95 masks to Singapore’s national stockpile.12 Despite Beijing’s sharp criticism of countries (such as Singapore) that had placed travel restrictions on Chinese travellers,13 Singaporean authorities in fact continued to work with China away from the spotlight to stem the spread of the virus, cooperating in health, economic and other sectors. The donation of masks was a testament to the ongoing cooperation and strong bilateral relations built up between both countries over time.14

Fishing Nets

Good bilateral relations are one means by which Singapore has ensured sufficiently open borders for continued trade of essential goods during the pandemic. Singapore has also cast a wider net to secure trade and supply links with many other like-minded countries.

On 25 March 2020, shortly after Malaysia’s lockdown, Singapore, Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Myanmar and New Zealand made a joint commitment to ensure trade lines remain open in order to facilitate the flow of goods and other essential supplies.15 Later, countries such as Lao PDR, Nauru, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay and China also came on board this Joint Ministerial Statement to ensure the continuity and interconnectivity of supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following this joint statement, on 15 April 2020, Singapore and New Zealand launched a Declaration on Trade in Essential Goods for Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic, facilitating the movement of over 120 different essential goods.16 The first shipment of essential items arrived in Singapore a week later on 22 April, containing more than 20 tonnes of meat, including beef and lamb.17

Figure 5. The first shipment of essential supplies being unloaded from an Air New Zealand plane at Changi Airport.

Source: Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore 18

The ability to cast these “fishing lines” and “fishing nets” are the result of Singapore’s past efforts in maintaining warm and longstanding bilateral and multilateral relations. These efforts have been critical in helping a small sampan like Singapore weather the worst of storms. However, is the sampan too dependent on these lines and nets? What will happen if it encounters a far greater crisis?

Singapore as Sampan 2.0

Beyond the Sampan

As early as 2018, Minister for Trade and Industry Chan Chun Sing has argued that in order to grow Singapore’s economy in the face of shifting global production and supply chains, Singapore would need to “move from getting others to trade with us, to trade through us, to also include for others to trade on our Singapore platforms”.19

Minister Chan cited the example of Port Authority of Singapore (PSA), which participates in a network of ports across the world, stretching from the Americas to Asia, from Europe to the Middle East, making it a global port and supply chain operator that competes at the supply and system network level rather than the port level. Today, PSA is moving beyond even this, by attracting partners to use the PSA platform, regardless of where the trade flows are—akin to having its own “Intel chip” on the operating system of global trade flows.

The argument being made is that it is not enough to have fishing lines and fishing nets in our sampan. Instead, Singapore must transcend the physical constraints of our sampan circumstances by developing and exporting home-grown pioneering technology and know-how to other countries, so we stay relevant and connected even during supply chain shifts.

Singapore must transcend the physical constraints of our circumstances by developing and exporting home-grown pioneering technology and know-how to other countries.

Inside the Sampan

Singapore also needs to innovate and use technology to push frontiers in the manufacture of essential goods and local food production. For example, Singapore decided to ramp up local production of surgical masks once the coronavirus hit China as we anticipated that various countries would start to impose export controls on masks.20

Local food production is also necessary to ensure food security in Singapore in the event of disruption of trade links. Singapore has set the goal for home-grown produce to meet 30% of Singapore’s nutritional needs by 2030, also known as the “30 by 30” goal.21

Figure 6.Then-MEWR announced its goal for home-grown produce to meet 30% of Singapore’s nutritional needs by 2030.

Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited.

Permission required for reproduction. 22

In other words, keeping sampan Singapore afloat calls for more than just good fishing lines and fishing nets. A whole-of-nation effort is needed to grow local production, support local produce and innovate to be ready for any future storms that come our way. All in the sampan must row in unison.23

Reiterating the point that Singapore is still a “sampan” and not a “cruise ship”, PM Lee has characterised Singapore as an upgraded “Sampan 2.0”. In PM’s telling, Singapore had become a stronger and more prosperous nation over time. However, it remained vulnerable to external forces and had to keep striving to do better.24

A whole-of-nation effort is needed to grow local production, support local produce and innovate to be ready for future storms.

To me, an improved sampan 2.0 is one with an array of fishing lines, fishing nets, and which is powered by locally-developed, in-demand global technology that improves our connectivity with the world. It should be steered by wise captains, supported by a strong and resilient rowing crew, as it ventures into uncharted waters or weathers stormy seas.

Sampan 2.0 may even look to be a speedboat one day. But it can never be complacent, and must always be on the move. As Aristotle Onassis, a Greek shipping magnate, once said “We must free ourselves from the hope that the sea will ever rest. We must learn to sail in high winds.”

NOTES

- Sumiko Tan, “Singapore Remains a Sampan, but an Upgraded 2.0 Version: PM Lee”, The Straits Times, October 30, 2013, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/world/singapore-remains-a-sampan-but-an-upgraded-20-version-pm-lee.

- Joyce Lim, “Singapore GE2020: Don’t Rock the ‘Singapore Sampan’, ESM Goh cautions”, The Straits Times, July 8, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/dont-rock-the-singapore-sampan-esm-goh-cautions.

- Koh Buck Song, “Sink the Old Sampan, S’pore Now a Cruise Ship”, October 30, 2013, The Straits Times, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/sink-the-old-sampan-spore-now-a-cruise-ship.

- See Note 1.

- Audrey Tan, “Coronavirus: Politicians, Supermarkets Urge Calm amid Panic-Buying of Groceries”, The Straits Times, February 7, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/coronavirus-fairprice-chief-urges-calm-amid-panic-buying-of-groceries-singapores.

- Singapore Food Agency, Annual Report 2019/2020, p. 17, https://www.sfa.gov.sg/

- See Note 5.

- Clement Yong, “Coronavirus: Most Try To Toe the Line, but Crowds Still Seen at Supermarkets, at Parks and Beaches in Singapore”, The Straits Times, April 10, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/coronavirus-most-try-to-toe-the-line-but-crowds-still-seen-in-supermarkets-at-parks-and.

- Clement Yong, “Most Supplies from Malaysia Delivered As Usual: Chan Chun Sing”, The Straits Times, March 19, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/most-supplies-from-malaysia-delivered-as-usual-chan.

- Ibid.

- Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore, “Singapore and Japan Agree to Deepen Bilateral Cooperation to Combat Covid-19”, 1 May, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/Newsroom/Press-Releases/2020/05/Press-Release---Singapore-and-Japan-Agree-to-Deepen-Bilateral-Cooperation-to-Combat-COVID-19.pdf.

- “China Donates More than 500,000 Face Masks to Singapore’s National Stockpile”, CNA, May 5, 2020, , accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore.

- Kayla Wong, “China Slams Countries that Ban Chinese Travellers, Says Travel Restrictions an ‘Overreaction’”, Mothership, February 2, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://mothership.sg/2020/02/china-travel-restrictions-overreaction/.

- See Note 12.

- “Singapore, 6 Other Countries Committed to Maintaining Open Supply Chains: Joint Statement”, CNA, March 25, 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/.

- Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore, “Singapore Concludes Negotiations with New Zealand for Declaration on Trade in Essential Goods for Combating the Covid-19 Pandemic”, April 15, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/Newsroom/Press-Releases/2020/04/Press-Release--SingaporeNew-Zealand-Declaration-on-Trade-in--Essential-Goods-FINALv2.pdf.

- Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore, “Singapore Receives Essential Supplies from New Zealand”, April 22, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/Newsroom/Press-Releases/2020/04/Photo-release-of-first-shipment-of-essential-supplies-from-New-Zealand-to-Singapore.pdf.

- Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore, “Singapore Receives Essential Supplies from New Zealand”, April 22, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/Newsroom/Press-Releases/2020/04/Photo-release-of-first-shipment-of-essential-supplies-from-New-Zealand-to-Singapore.pdf.

- Chan Chun Sing, “Speech by Minister for Trade and Industry Chan Chun Sing in Parliament at the Debate on President’s Address”, May 14, 2018, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/Newsroom/Speeches/2018/05/Speech-By-Minister-For-Trade-And-Industry-Chan-Chun-Sing-In-Parliament-at-the-Debate-On-Presidents-A/speech-by-minister-for-trade-and-industry-chan-chun-sing-debate-on-presidents-address--checked-again.PDF.

- Calvin Yang, “Coronavirus: Singapore Boosting Production of Masks since February”, The Straits Times, May 7, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-boosting-production-of-masks-since-feb.

- Cara Wong, “Demand for Local Produce Must Complement Supply in Local Food Production: Amy Khor”, The Straits Times, July 18, 2020, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/demand-for-local-produce-must-complement-supply-in-local-food-production-amy

- Ibid.

- See Note 2.

- See Note 1.