Incentivising New Partnerships for Social Impact

Digital Special Edition (March 2021 Update)

New Normal, New Needs

What do Deliveroo, Food Panda, and Grab, have in common?

With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Singaporeans have relied on these companies to mobilise tens of thousands of drivers to deliver food.1 Yet ten years ago, not one of these companies existed. Such companies have scaled exponentially from fledging start-ups to effective platforms in a short time, thanks to the injection of funding and expertise from venture capital.

Might the experience of growing these companies offer lessons for how we can build social impact organisations to better address the next generation of social issues?

The COVID-induced new normal has accentuated core public needs. There is the need to do more with less, given that available financial, human and other resources must be devoted to tackling the pandemic and supporting a shocked economy. There is also the need for social innovation, since COVID has disrupted many conventional services and will have lasting economic and social consequences in the longer term. In this challenging environment, Singapore will need to mobilise the full potential of every sector in solving complex social issues.

The pandemic has shown that Singaporeans can take collective action for the public good.2 But harnessing the full potential of each sector in a systematic and constructive way will require the use of more sophisticated partnership tools that are able to align the incentives of the private sector and build the capabilities of the social sector. One tool that we can adapt to accomplish this is Pay For Success—a tool that helps to incentivise the equivalent of venture capital for social impact.

Hidden Potential Exists To Address New Needs

To see why this tool might make sense, let us turn briefly to Singapore’s experience encouraging innovation in the private sector.

In the for-profit sector, start-up innovation is enabled by an ecosystem that provides the right type of funding and capability building at every stage. Initially, start-ups are backed by individual angel investors, who offer early funding and mentorship to entrepreneurs to establish an initial proof-of-concept. Next, they are backed by professional venture capitalists, who provide systematic support to build up the organisation, create the right business model and optimise the product so that there is a proof-of-value to the market.

Finally, successful innovations are eventually acquired by the big companies or the public markets, in order to get to the scale they need to mature.

Figure 1. Private Sector Stages of Innovation.

Source: Tri-Sector, 2019 3

Like countries such as Israel,4 Singapore has sought to nurture its own venture capital ecosystem in order to accelerate the growth of start-ups.5 For Singapore, the challenge has been the risk-reward ratio for venture capital—so the government has offered matching funds and preferential investment terms as incentives.6

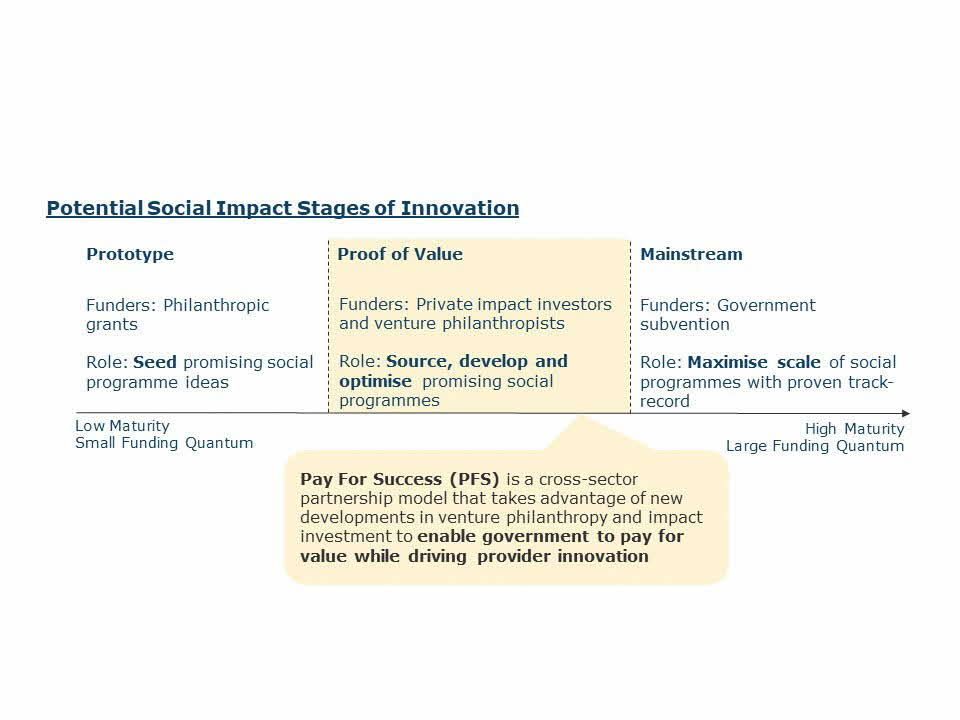

In the social impact world, the opportunities and challenges are different.

Traditionally, the social sector has had significant funding, but that funding has been at both ends of the innovation spectrum. On the one hand, philanthropy and individual givers have provided relatively small start-up grants. On the other hand, the government has scaled up mature solutions, hence fulfilling a role analogous to that played by Initial Public Offerings (IPO) in the private sector. There are few, if any, organisations that specialise in helping to build and optimise promising social impact solutions so that they can cross the chasm between initial idea and “IPO-readiness”.

Figure 2. Potential Social Impact Stages of Investment.

Source: Tri-Sector, 2019 7

The opportunity for change lies in the assets and capabilities of wealth management. Across the world, a new generation of wealth owners are asking their wealth managers to apply their assets towards more social causes, in what is known as “impact investing”.8

Across the world, a new generation of wealth owners are asking their wealth managers to apply their assets towards more social causes, in what is known as “impact investing”.

Singapore is a wealth management hub. There were S$3.4 trillion in assets under management in Singapore in 20189—this is more than 1,000 times the S$2.7 billion of tax-deductible philanthropy given in FY 2017.10 If we were to encourage even 0.1% of these wealth assets to be deployed for our social causes, it would be tantamount to doubling the amount of philanthropic giving.

The same holds true from a capability perspective. While we have focused significant attention on bringing in the skills of the technology industry to bear on social issues, the ICT industry in reality contributed only 4.3% of Singapore’s GDP last year. By comparison, the financial services industry employed more than triple that, or 13.9% of the economy.11

Would it be possible to draw in these tremendous assets and capabilities, to do for the social impact world what venture capitalists have successfully done for the commercial world?

Such an approach would call for a shift in what we think of as contribution. n the private sector, venture capital does not provide free money, but it does play a critical role in the start-up world. Similarly, Singapore’s untapped assets and capabilities may not come in the form of donations or volunteers, as is the case today, but can still be of significant value in the new normal on several fronts:

1. Risk-Taking Appetite. As taxpayer dollars become scarcer, it will become harder to take risks with them. Impact investors can complement the public sector in taking on new risks. Just as venture capital funders are willing to take bold bets in search of financial return, impact investors make bold investments in search of impact “return”. This focus on impact rather than financial return allows these impact investors to take bets on solutions that are too early-stage for taxpayer funds to support, or would otherwise be unattractive to the market. By letting the private sector continue to push boundaries with upstream preventative solutions and more radical ideas, government could focus its precious dollars on core services or more proven solutions, only paying for what is proven to work.12

2. Innovation Bandwidth. As problems become more complex, innovation will require more attention—which may become increasingly stretched. Impact investors can complement the government in bandwidth: by helping to scout out new solutions from different sectors and around the world, doing the legwork to translate these into implementable ideas on the ground, and optimising existing solutions (such as through digitalisation) so they can be cost-effective and scalable.

3. Capability Building Skills. As we ask for more partnership and initiative from the people sector, they will need to develop new capabilities. While large charities can perhaps draw on their own boards and reserves for such capability building, this is more challenging for smaller charities seeking to innovate. From the government perspective, it may also be difficult to build bottom-up organisations from a top-down vantage point. Impact investors can help to nurture a new generation of social impact organisations by contributing their networks and expertise, just as venture capitalists do for start-ups. They can professionally and systematically help charities build high-calibre boards, improve management, introduce best practices, drive technology adoption, call in specialist consulting, broker new partnerships, and so on.

While these value-adding contributions may be less familiar in the social impact world, they are in fact the building blocks of the financial service industry in which Singapore has developed such deep expertise. After all, the premise behind such financial services is that “money is not just money”, and that significant value can be added in how that money is deployed, managed, and applied.

Impact investors can help to nurture a new generation of social impact organisations by contributing their networks and expertise, just as venture capitalists do for start-ups.

Policy Action Is Required To Draw on This Potential

The challenge to drawing in these impact investors is different from the venture capital case.

Impact investors are willing to take a far lower rate of return than mainstream venture capitalists are. Many simply hope to preserve their original funds so as to redeploy these funds to future programmes over time. The problem is that the incentive system surrounding social impact organisations does not reward innovation. If we want to mobilise these private resources for our social ends, then we will need a different kind of partnership tool that better aligns incentives.

In traditional start-ups, customers pay for services out of their pockets, based on the value they derive from the services provided. Such payments eventually allow the venture capitalists who helped to build the start-ups to replenish their capital and invest in more start-ups in future. In addition, if customers do not find the services provided valuable, they switch. This means that start-ups and their backers have an incentive to invest in creating better services that customers will pay for.

However, in the social impact world, beneficiaries usually do not pay for the services themselves. Instead, someone else buys these services on their behalf: usually a philanthropic institution or the government, or—in the case of a social enterprise—a market consumer. In each case, what is paid is not usually based on the value of the social outcomes generated. A non-profit that prevents recidivism (such as a drug rehabilitation centre), is usually paid on a cost-reimbursement basis for the number of people served, rather than based on the social value of relapses avoided. A social enterprise’s restaurant customer may pay a premium for their meal, but it is rarely commensurate with the positive social benefits enjoyed by its beneficiaries.

As a result of this mismatch between social value and funding, there is a market failure—society fails to invest enough to produce the valuable social good. In addition, the “customers” of the social impact world such as government and philanthropy find it hard to switch their buying behaviour on the basis of value, because it has been traditionally difficult to measure the value of often intangible social benefits. This further disincentivises investment towards creating more effective solutions.

The policy solution is similar to what has already been done for carbon: correct the market failure by internalising the externality—making intangible benefits or costs more explicit to the market.13 In the case of carbon, a tax is imposed to better reflect its true environmental cost and discourage production. Here, like a “reverse carbon tax”, we need to price in the value of positive social benefits and provide an “impact bonus” for social outcomes.

It turns out that a model called Pay For Success (PFS), sometimes known as a Social Impact Bond, has already been used to do just that. There is potential to adapt this tool for Singapore’s needs in several tangible areas.

Like a “reverse carbon tax”, we need to price in the value of positive social benefits and provide an “impact bonus” for social outcomes.

There Are Already Several Tangible Areas of Opportunity

The PFS tool was first pioneered in 2010 in the UK. It has since spread to 32 countries around the world in 190 projects worth over US$400 million, including in Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong.14 In each context, the tool has been adapted to different issue areas and optimised for different policy objectives. Singapore’s unique context, in which government has had a strong role in solving social issues, calls for similar adaptation and creative application.

Broadly, a PFS project has three steps. First, the government decides to create a partnership for a particular area of policy concern, for which it will internalise social externalities by committing to pay an “impact bonus” for desired social outcomes. Next, impact investors work with innovative service providers to build and test new solutions. Finally, a rigorous evaluation is conducted, and government repays the coalition based on the social value of the successful social outcomes achieved.

While in the West cost-savings has been strongest objective, in developed Asia, the tool has been adapted to also emphasise innovation and partnerships. In Japan, for example, the Cabinet Office has established a Pay For Success Promotion Office under its broader mandate to encourage Public Private Partnership.15 In Hong Kong, it is championed by the Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Fund, which is meant to spur cross-sectoral collaboration for social innovation.

In Singapore, PFS projects could be a useful way to address the needs of the new normal. In our context, it is not just about expanding the pool of funders, but also about jumpstarting innovation, building capabilities, and deepening the involvement of society in solving new social problems. For instance, projects currently under development include:16

• High Skilled PWD Employment. Given the current economic climate, it is hard to encourage employers to hire inclusively. However, there is a skills crunch in certain high-skilled jobs, further exacerbated by global movement controls. Would it be possible to create more options for tertiary-educated Persons with Disability to fill these high skilled jobs, and generate more economic value in the process?

• Youth Mental Health. The WHO estimates that 75% of mental illnesses develop by the age of 25. The circumstances of the pandemic have exacerbated this risk. While much has been done for the general population, would it be possible to build a convenient and effective system to prevent youth at high risk of developing mental illnesses from doing so, and hence reducing downstream medical and social costs?

• Youth and SME Skilling. Many SMEs today will need to retool and rehire for new economic realities. But most will not have the funds or risk appetite to make such investments at this time. Would it be possible to provide the right capital, risk sharing, and tailored training so that SMEs can get the skills they need—and perhaps even hire more today?

Apart from these areas, PFS has been used in projects overseas for issues of persistent concern in Singapore, such as: reducing drug offender recidivism, preventing diabetes and managing chronic kidney disease, and helping with active ageing so as to reduce the burden of care. In each of these areas, the PFS model can add value, if it is suitably adapted for Singapore’s unique system.

Not a Swiss Army Knife but a Scalpel

We should be clear that tools like PFS are not a swiss army knife for every problem, but a scalpel. There are risks in application that need to be mitigated, and they should also be judiciously applied to the right types of problems.

The first risk is that there may be objections to government paying to incentivise societal participation, capability building, and risk-sharing. The second risk concerns cannibalisation: that we may turn existing donors who would otherwise have been willing to give for free into investors who ask for their money back. The third risk concerns transaction costs: it takes time and money to try a new process, convene stakeholders, negotiate terms and conduct evaluations.

Counterintuitive as it may seem for government to incentivise civic participation, the reality is that we are already doing so today. Singapore encourages donations by providing a 250% tax deduction for each dollar donated.17 The government is already paying to build capabilities in the people sector, most recently via the S$350 million Community Capability Trust.18 Finally, we are already incurring hidden costs in the form of government staff time required to develop and manage solutions, and the cost of failures when pilot trials do not work out as planned.

Counterintuitive as it may seem for government to incentivise civic participation, the reality is that we are already doing so today.

The question should therefore not be whether to pay, but whether the value-add is worth the cost. To mitigate the risk of unfair outcomes and to ensure that the government is in fact stretching its dollar, there needs to be open discussions between the sectors involved, objective cost-benefit analyses, and rigorous evaluations. Fundamentally, given the impact-focused mandates of this new class of investors, most only seek to capture a fraction of the total social benefits generated, so there is usually room for government to get a “good deal” once all risks and benefits are accounted for. For example, Bridges Outcomes Partnerships in the UK has invested in £32 million of PFS projects, which have in turn generated an estimated £84 million of value for the government.19

To mitigate the risk of unfair outcomes and to ensure that the government is in fact stretching its dollar, there needs to be open discussions between the sectors involved, objective cost-benefit analyses, and rigorous evaluations.

To mitigate the risk of cannibalisation, the government could target more hands-on impact investors rather than traditional donors; it could also ask existing donors to give to PFS projects above and beyond their traditional allocations. The question to then ask is: what is the net effect, even if cannibalisation were to happen? As an analogy, skills-based volunteering has not led to the decline of traditional volunteering—instead, it has helped to draw in new types of volunteers, get more out of existing ones, and raise the profile of volunteering as a whole. Similarly, even if some donors were to switch to impact investing, so long as there is a net gain in benefit, it should be encouraged.20

As for transaction costs, some governments abroad have made the PFS process more efficient and cost-effective, such as by setting up standardised Outcomes Funds that allow for social externalities to be internalised on multiple projects. The UK government has set up six such funds at present of between £15 million to £60 million each in diverse issue areas.21 These Outcomes Funds specify a list of social outcomes and the government’s willingness to pay for those outcomes, thereby stimulating social investment to achieve these outcomes.

Above all, it is key to match the right tool to the job. We are fortunate in Singapore to have an array of effective policy instruments, allowing us to use tools such as PFS as they are intended: as a complement to a solid core of services, targeted at areas where complex problems need to be solved, in which cross-sector collaboration adds value. In the post-COVID new normal, there will be more and more of such areas to tackle. We will need every tool at our disposal.

PFS should be used as a complement to a solid core of services, targeted at areas where complex problems need to be solved, in which cross-sector collaboration adds value.

NOTES

- Joyce Lim, “Coronavirus: New Players Ride the Food Delivery Wave, Bringing More but Also Patchy Service”, The Straits Times, June 7, 2020, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/manpower/new-players-ride-the-food-delivery-wave.

- For example, the Majurity Trust, a ground-up philanthropic organisation, supported 150 citizen-led initiatives via its SG Strong Fund alone.

- Tri-Sector Internal Analysis, 2019.

- The Israeli program was called Yozma, where the government set up a US$100 million fund in 1992, US$80 million of which went to seeding foreign venture capitalists. See Gil Avnimelech, “VC Policy: Yozma Program 15-Years Perspective”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.academia.edu/24003922/VC_Policy_Yozma_Program_15_Years_perspective.

- HexGN, “The Top Ten Startup Cities to Watch Our in 2020”, February 6, 2020, accessed February 1, 2021, https://hexgn.com/hexgn-city-ranking-the-top-ten-startup-cities-to-watch-out-in-2020/.

- Schemes included Early Stage Venture Fund: S$140 million to match private VC funds on 1:1 basis, SPRING Seeds Capital: S$75 million to co-invest with private VC, Technology Incubation Scheme: investing 85% of capital in a start-up when private investors put in 15%, with an option to buy over government’s stake in the start-up within three years, and Temasek: providing S$100 million to subsidiary Vertex Venture Holdings as well as S$90 million to four local VCs.

- Tri-Sector Internal Analysis, 2019.

- Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/83814145-2166-3ef3-9bdb-3d4f6fa8c987.

- Monetary Authority of Singapore, “2018 Singapore Asset Management Survey”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.mas.gov.sg/-/media/MAS/News-and-Publications/Surveys/Asset-Management/Singapore-Asset-Management-Survey2018.pdf.

- Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth, “Commissioner of Charities Annual Report for the Year Ended 31 December 2018”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.charities.gov.sg/Publications/Documents/Commissioner%20of%20Charities%20Annual%20Report%202018.pdf.

- Department of Statistics Singapore, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.singstat.gov.sg/modules/infographics/economy.

- For example, the Hong Kong government had a budget surplus, but wanted to incentivise upstream innovation to tackle the problem of underachievement and lack of social integration of migrant schoolchildren. Tri-Sector worked with the Hong Kong Council of Social Services and Oxfam to scale up a pilot project using a new cost-efficient delivery model with the goal of closing the language achievement gap of migrant schoolchildren in the early childhood system. Private sector funders are providing the capital and capability building upfront, and if the program in fact closes the achievement gap, the government will repay the private funders based on the estimated value of the resulting social benefits and avoided downstream costs. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- VNational Climate Change Secretariat, “Carbon Tax”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.nccs.gov.sg/singapores-climate-action/carbon-tax/.

- Brookings Institution Global Impact Bond Database, April 1, 2020, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Global-Impact-Bonds-Snapshot-April-2020.pdf.

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, “PFS: Pay for Success”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www8.cao.go.jp/pfs/index.html.

- Tri-Sector Internal Analysis, 2020.

- Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore, “Donations and Tax Deductions”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.iras.gov.sg/irashome/Other-Taxes/Charities/Donations-and-Tax-Deductions/.

- Goh Yan Han, “Singapore Budget 2020: $350m To Support Social Service Agencies and Build Giving Culture; Wage Offsets for Hiring Those with Disabilities", The Straits Times, February 18, 2020, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-budget-2020-350-million-to-support-social-service-agencies-and-build-giving.

- Bridges Outcomes Partnerships (website), accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.bridgesoutcomespartnerships.org/.

- Bridges Fund Management, “Bridges Closes Second Social Outcomes Fund at Extended Hard Cap of £35m”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.bridgesfundmanagement.com/bridges-closes-second-social-outcomes-fund-at-extended-hard-cap-of-35m/.

- Government Outcomes Lab, “UK Government Outcomes Funds for Impact Bonds”, accessed February 1, 2021, https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/the-basics/outcomesfunds/outcomes-funds/.