How To Be Innovative

ETHOS Digital Issue 13, Oct 2025

Innovation Is Hard

Everybody wants to be more innovative, but it is rare to see someone actually succeed. Despite talk about moving to the cloud, the rise of AI, or whatever digital transformation is, most organisations are still stuck with legacy systems and manual processes. Some try to tackle the problem culturally, telling people to be more agile, bold, and creative. But this rarely achieves much more than everyone getting new t-shirts. It’s not that technology and culture are not important. They are. It is that the root causes for these problems run much deeper. To solve them we first have to understand why innovation, especially in the public sector, is in fact really hard.

First you have to work with people who do not want anything. When we started building FormSG, we talked to dozens of agencies, ministries, and stat boards. Most of them said the same thing: “Who are you?”; “Why are you here?”; “Please go away!”. The only person who wanted help was someone at the National Environment Agency, whose job it was to collect pigeon complaints. Singapore has a lot of pigeons and Singaporeans like to complain. So of course there was a form for people to complain about pigeons. When he heard we could help automate his job, he was very happy.

Then you have to work with people who want too many things. When Parking.sg was getting close to launch, the three partner agencies (HDB, LTA, URA) all suddenly had long lists of features they needed from the app. They wanted it to manage season parking, pay fines, support family sharing, and a hundred other ideas. At that point we couldn’t even do refunds yet. We only managed to launch the app because I persuaded them to let us do our alpha testing first, and we would then try to add those features later. Thankfully once it was clear people liked the app, they realized the extra features were not important.

Perhaps the worst problem is that when you actually do launch something, many people get very upset. Our team helped with the new ActiveSG app last year. The old system was expensive, unmaintainable, and there were challenges working with the vendor. We knew it had to be replaced. We worked very hard over three months to hit the handover date. It was not perfect but we had a solid system. But say you are a parent wrangling three kids to swim class, only to suddenly be told when you show up that you have to use a new app: no matter how good it is, you are going to be annoyed.

So innovation is hard. Oddly enough, it is rarely the technology that is difficult. And it is not enough to tell people to try harder. You have to understand the underlying systems that allow some teams to be innovative—while others can only talk about it. While there is a lot to unpack, for me it comes down to three things: outcomes, structure, and iteration.

Innovation Needs Clear Outcomes

A common problem in innovation programs is that we do not know what we are innovating for. Are we trying to reduce costs? Improve usability? Save time? Or are we just trying to do something “new”? Without a clear goal your only reference point is what you are already doing. Then your only source of feedback is whether anyone is unhappy about change: and someone always is. So you get stuck, wanting to innovate but not able to move.

Conversely, when you have a clear goal you can be very flexible about how to get there. In the private sector, it might be profit. In F1, it is lap time. In AI, it is quality benchmark scores. Once you know what you are trying to achieve, you can stop obsessing over how you achieve it. Good metrics tell you what to care about, but also what not to care about.

Practically, even when a public sector team manages to overcome the bureaucracy, technical challenges, and operations to build something really good and present it to leadership, it often gets shot down with a simple “That’s not how we do things”. This is not really anyone’s fault. It is hard to make something new happen when your job is to make sure nothing bad ever happens.

Good metrics tell you what to care about, but also what not to care about.

As an example, AskGov is our Q&A system for the government. Originally, when we did product reviews we would spend a lot of time diving into bug fixes, new buttons, and various design details. While these are all good details for the team to care about, it was not productive for them to walk me through every detail. All this changed when we aligned on just two metrics I would care about: Reducing call volume and increasing citizen satisfaction. If calls went down while satisfaction went up, then I did not need to care exactly how the team went about it. On the other hand, if call volume stayed the same and citizens were not happier, then I also did not care what the team had built. Clear outcomes gave the team more freedom to innovate because it gave me a better way to know if it was working.

This also means that you need to match your performance management to your desired results. Innovation awards and recognition are great, but the moment reviews come around and people see they are still being judged on something else, all that motivation disappears. This is especially important because, by default, performance ratings are based on your manager’s impression of you. If you do not deliberately tie performance to outcomes, then you will get a lot of innovation theatre: Projects that get attention and hype, but ultimately do not deliver anything. Outcomes are only real when anchored in accountability.

Innovation Needs Structural Space

Traditional organisations are based on a military structure: top down, central decision making, optimised for command and control. They are designed for a small group of people to make decisions, and for everyone else to align quickly and consistently. This is great when you already know what to do and just need to execute. It is not so great if you need to figure out what needs to be done.

Just telling people to innovate does not work. You need to build structures that give them the space to do it. Innovation, almost by definition, requires creativity and autonomy. This is the opposite of command and control and so you need to design the organisation in the opposite direction.

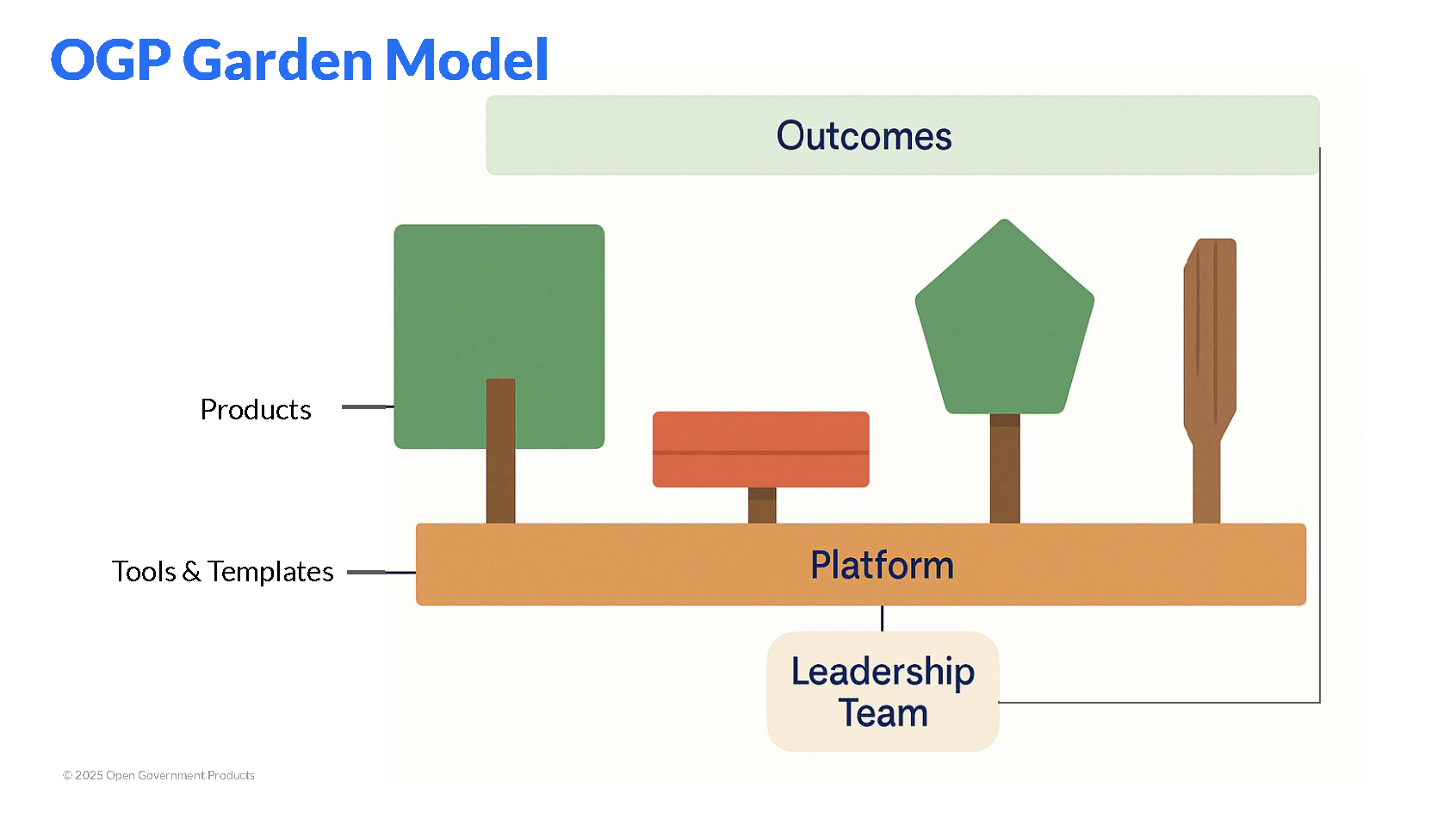

At OGP, we designed the team to be a support structure rather than a command structure. The job of management is to provide the space, resources, and tools for the teams to work as effectively as possible, while still holding the team accountable for their outcomes. The team decides what to build, how to build it, and how to prioritise. That is where innovation happens.

In a Rube Goldberg machine, a marble might knock over some dominoes, which flips a switch, which pushes a broom and so on, eventually turning a light on. If you removed even a single domino, the whole thing would stop working. With traditional structures, we tend to form human Rube Goldberg machines. The CEO tells the director, who tells the team lead, who tells the procurement manager, who tells the vendor, who tells the project manager, who tells the developer. If any part of that chain changes, the whole company might stall. It is no surprise then when nobody innovates.

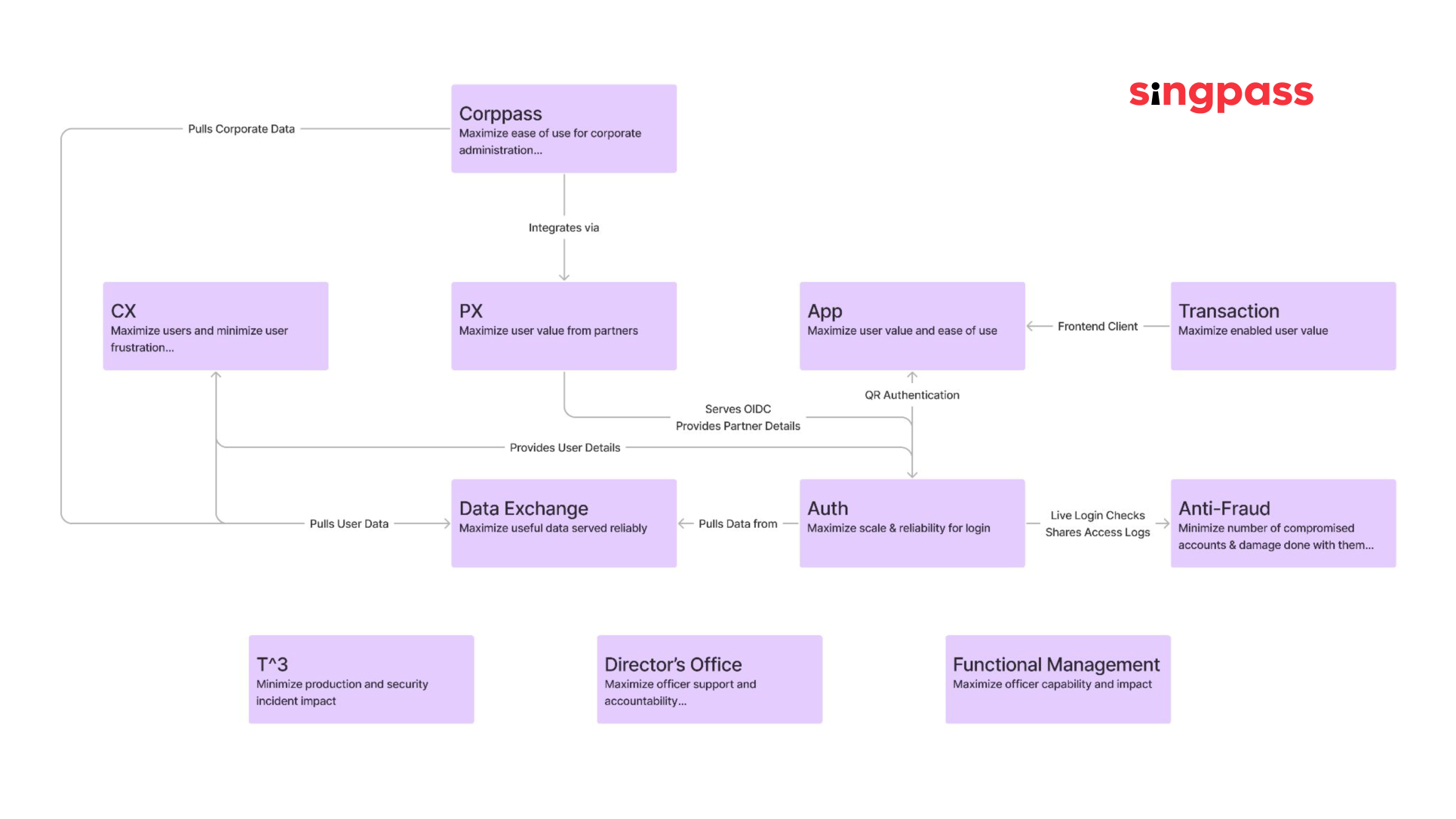

In developing Singpass, we previously had a lot of Rube Goldberg problems. Even minor launches required coordination from at least six different groups and dozens of people. To address this, we restructured to group people around each product with a clear goal and explicitly mapped out the main ways the different teams depended on each other. For example, the authentication team had the goal ‘Maximise scale and reliability of logins’, while the customer experience team’s goal was to ‘Minimise user frustration’. Each new team was cross-functional (design, frontend, backend, operations). This meant that most of the work could happen within each team, only occasionally requiring cross team collaboration.

To be clear, every organisation structure makes some things easy and other things hard. The key is to make the most common and important things easy and accept that rare and less important things will be hard. So, if you want to be innovative, you need to structure for it deliberately. This means providing support, reducing dependencies, and creating space for creativity and autonomy.

Innovation Needs Iteration

Even with clear goals and a good structure, innovation fails most of the time. At OGP, we run a month long hackathon at the start of each year. The team explores different ideas, builds quick prototypes, and takes the best ones to launch. We start with around 100 ideas. About 25 make it to prototypes. Fewer than five of these become full products. It is not that the other ideas are bad. There are just a lot of reasons they may not work. Maybe the operations were too complex. Maybe the integrations were not ready. Maybe the users did not think there was a problem in the first place.

This means that even if a very smart leader has an idea, the likelihood that it fails is 95%. Even if a committee thoroughly gathers requirements and debates scope for months, only 1 in 20 will succeed. It is not that they did their job poorly. These are just probabilities you have to work with.

To get good ideas, you have to start with a lot of ideas, then experiment to find out what can actually work. What makes an idea valuable is not the idea itself, but whether it has been refined through iteration.

One example is Armory, an app we built for SCDF to help firemen track their equipment. After a year of development and iteration we got something really good rolled out to all the fire stations. Moving off paper made equipment checks easier, tracked necessary maintenance, and improved operational readiness. Since the firemen loved it, we thought the paramedics could use it too.

“Pressing the YES/NO button 461 times. Stop asking redundant questions." — Paramedic

They hated it. Ambulances carry hundreds of small items and medications. Armory forced them to check every item, every shift, even ones they had not used. This added up to over 400 different checks every day. It was slow, frustrating, and not worth it. It is surprisingly hard to anticipate why an idea might not work. Even good ideas can fail when subtle differences between seemingly similar users turn out to matter more than expected.

So we kept iterating. We cut unnecessary checks. We added item groups, so teams could clear items in bulk. We introduced scheduling, so some items only needed to be checked weekly or monthly. This cut the number of daily checks from over 400 to less than 70. It took lots of feedback and testing, but eventually it became something paramedics actually wanted to use. With so many ways for ideas to fail, iteration is the only way to successfully innovate.

Why We Need To Be Innovative

Beyond thinking about how we can innovate, we need to also ask why we should. After all, the Singapore system is pretty good. Why bother with innovation instead of just focusing on keeping things running instead?

For me it is because, while we are doing relatively well, there are still a lot of people who need help. People who just live with medical problems because getting treatment means taking too much time off work. People who get scammed out of their life savings because it was too hard to protect yourself online. People who could have avoided life changing issues if they only got the right support at the right time just a little bit earlier. If we say “This is good enough” what we are saying to these people is “This is what you have to live with”.

Innovation is about being honest that we still have real problems to solve and hard work to do in solving it.

Innovation is not about being cool, or getting attention, or building excitement. It is about being honest that we still have real problems to solve and hard work to do in solving it. We are not here to admire how well the system works for most people. We are here to make sure it works for everyone.