Sustainability as Behavioural Change: Nudging the Good, Discouraging the Bad

ETHOS Issue 24, August 2022

Singaporeans can do more to adopt eco-friendly habits, particularly in recycling and reducing waste. Perceptions that the governments and/ or businesses have a larger role to play help explain why some individuals do not do more. In a Kantar Public study, 83% of respondents from Singapore said they would accept stricter rules and environmental regulations.1 The assumption underlying this sentiment is that people expect governments and businesses to take the lead, compared to individuals. Short of regulation and legislation, there is a limit to what governments and businesses can do to change individual behaviours.

People expect governments and businesses to take the lead, but there is a limit to what they can do to change individual behaviours.

The gap between people’s beliefs and actions, and their expectations that governments and the private sector play a bigger role, should inform our approach to tackling climate change problems. It is laudable that we have achieved the first step to changing behaviour—recognising the importance of fighting climate change. But we next need to convince individuals to adopt more demanding individual eco-friendly habits, and to find ways to make these habits easier to adopt. The end goal is to see people adopting sustainable and impactful behaviours as part of their regular lifestyle.

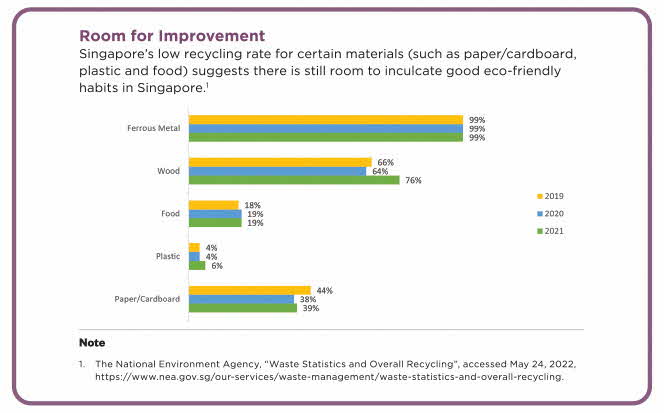

Figure 1. Recycling Rate of Selected Waste in Singapore (2021). Source: National Environment Agency

What do surveys say about Singaporeans’ green habits?

Less Talk, More Action Needed

In the National Climate Change Secretariat’s 2019 climate change public perception survey, 60.9% strongly believed that individual action makes a difference in fighting climate change.1 Yet, only 34% of respondents from Singapore rated themselves between 8 and 10 in terms of their commitment to preserving the environment and planet, according to a Kantar Public study on environment and climate change in 2021.2 An inaugural Climate Index research by Overseas-Chinese Banking Corporation Limited, in partnership with Eco-Business, also found that Singapore residents scored only 6.5 on a 10-point scale in adopting green practices.3 In addition, the same Kantar Public study showed that 40% of respondents from Singapore did not think they needed to change their habits.4

Singapore’s domestic recycling rate is at a 10-year low of 13%.5 A study conducted by the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE) in 2021 with youths in Singapore also found that while the majority of respondents were already practising certain eco-friendly behaviours like switching off electrical appliances, turning off the tap when soaping hands and using fans instead of air-conditioners, fewer than 50% of respondents took up other habits like recycling, using reusable food containers for takeaways and composting food waste.6

NOTES

- National Climate Change Secretariat, “Climate Change Public Perception Survey 2019”, December 16, 2019, accessed May 24, 2022.

- Emmanuel Rivière, “Our Planet Issue: Accelerating Behaviour Change for a Sustainable Future”, Kantar Public, accessed May 24, 2022.

- Overseas-Chinese Banking Corporation Limited, “OCBC Climate Index”, August 17, 2021, accessed May 24, 2022.

- See Note 2.

- Gena Soh, “Recycling Bins to Be Given to Each Household to Raise Domestic Recycling Rate”, The Straits Times, January 14, 2022, accessed May 24, 2022.

- A. Lee, “Findings for Study on Environmental Perceptions of Youths” (Environmental Behavioural Sciences and Economics Research Unit, Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment, 2021).

What Does It Take to Make A Bigger Impact?

Some behaviours and actions are more environmentally friendly than others because they reduce the carbon footprint to a greater degree. These impactful behaviours often demand more effort. For such behaviours to be sustained, habits need to be formed.

A defining feature of a habit is when people behave automatically without much deliberation. Psychologist Wendy Wood has found that 43% of what people do every day is repeated in the same context and people slip back into their (good and bad) habits when they are distracted and/or overwhelmed.2

According to Wood and Neal, sustaining behaviour change requires a two-pronged approach: forming good habits while simultaneously breaking existing bad habits.3

Wood and Neal also identify several elements crucial to forming lasting habits.4

- Opportunities for the repetition of the same good habit, so that the behaviour becomes automatic. E.g., interventions in school requiring students to recycle all food waste.

- Context cues such as the physical environment or times of day to prompt the first step required of the desired behaviour. E.g., setting up a recycling corner next to the waste bin at home.

- Rewards to encourage repeated positive behaviours. E.g., receiving a small monetary incentive from recycling a glass bottle.

For recycling, forming good habits alone will not be sufficient, because efforts can be marred by bad habits like incorrect recycling. According to the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE), 40% of the contents in recycling bins cannot be recycled because of contamination (e.g., plastic bags with food waste) and/or non-recyclable materials (e.g., styrofoam, tissues, reusables).5 Similarly, SembWaste has reported that approximately 60% of what they handle in their facility cannot be recycled.6

Wood and Neal recommend three strategies to help break bad habits:7

- Remove context cues that trigger bad habits by leveraging key moments in life, such as recycling interventions targeting those who have just shifted into new housing estates.

- Alter the environment by making it difficult to continue with the bad habit. E.g., requiring recyclables to be sorted by waste type before placing it in the recycling bins.

- Vigilant monitoring of behaviour, so that timely feedback can be provided to halt automatic undesired behaviours. E.g., visual cues on the covers of recycling bins to remind what can be recycled.

For habit change to happen, we need to change the context within which we make decisions and act.

Government’s Role in Supporting Habit Change in Singapore

The physical environment around us—homes, shopping malls, the workplace—influences how we behave every day. Our actions are also influenced by other contextual cues like the time of the day, what others do in the same environment, and incentives shaped by government or corporate policies. For habit change to happen, we need to change the context within which we make decisions and act.

In this regard, governments can play an important role in promoting recycling habits by shaping incentive systems through regulations and/or working with businesses to reward positive behaviours, and influencing context cues (e.g., design and location of recycling bins).

Seeking to lower contamination in recycling bins, the NUS Zero Waste Taskforce conducted a trial to test a new “Recycle Right” bin design for the recycling of bottles, cans, and notes and cardboard.

Recycle Right!

The National University of Singapore (NUS) Zero Waste Taskforce conducted a study on contamination for recycling bins between January and March 2020. They found that the proportion of non-recyclables compared to all items in plastic recycling bins (i.e., contamination rate) was at a high of about 57% for University Town (Utown) and 46% for College for Design and Engineering.1

Seeking to lower contamination in recycling bins, the Taskforce conducted a trial to test a new “Recycle Right” bin design for the recycling of bottles, cans, and notes and cardboard.

The “Recycle Right” bins were designed with a number of features to help break incorrect recycling habits and encourage new habits:2

- A display showcase was installed at the top of each recycling bin, showing actual non-recyclable items from each bin.

- A lid was installed for each recycling bin as a timely prompt to disrupt automatic incorrect recycling habits.

- Bins were made transparent to reinforce positive behaviour; it showed people whether their actions were aligned with others who recycled right.

At the end of the trial, they found that the new Recycle Right bins was effective in reducing the contamination rate of plastic bottle recycling bins from about 60% to 27% in UTown.3

Following these promising results, the Taskforce collaborated with the National Environment Agency to trial the bins at two shopping malls. Results showed that the bins were effective in lowering the contamination rate of plastic bottle recycling bins in these malls from 79% to 29%.4

Prototype of the Recycling Right Bins. Source: National University of Singapore

Close-up of Display Showcase. Source: National University of Singapore

NOTES

- Deliang Loo and Harry Lim, “Nudging Proper Recycling: An In-Depth Waste Analysis”, Zero Waste NUS, accessed May 17, 2022.

- Sumita Thiagarajan, “NUS Student, 26, Hopes to Improve S’poreans’ Recycling Habits with New Bin Design”, Mothership, September 2, 2020, accessed May 17, 2022.

- Deliang Loo and Harry Lim, “Recycling Right Through Better Design”, Zero Waste NUS, accessed May 17, 2022.

- Zhangxin Zheng, “New Recycling Bins Piloted at JEM, IMM & Westgate Get Less Contaminants”, Mothership, May 2, 2022, accessed May 18, 2022.

What are the insights from the “Food Waste? Don’t Waste!” pilot programme?

Making It Easy to Recycle Food Waste!

In 2018, the Environmental Behavioural Sciences and Economics Research Unit (EBERU) of MSE, together with NEA, the People’s Association and Tampines Town Council, launched a Food Waste? Don’t Waste! pilot programme at the Tampines GreenLace HDB estate to gather insights on households’ food waste disposal behaviours and inculcate a habit of segregating food waste from general waste. Food waste was transported to Our Tampines Hub for recycling into fertiliser, liquid nutrient, and non-potable water.

The programme incorporated several behavioural science principles:

Make It Easy

|

All Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) access-controlled bins were coloured bright red and clearly labelled as "Food Waste Recycling Bin". These bins were placed near the ground floor lift lobby to maximise their visibility, convenience, and accessibility for both residents and waste collectors. Directional signs were placed at eye-level on every wall surface, to be visible to residents the moment they exited the lifts. A simple step-by-step bin operation guide was attached to each bin to ensure ease of use. |

Food Waste Recycling Bin Source: MSE |

Make It Timely

Each household was given a starter kit to guide them in starting on food waste segregation at home and disrupt existing food waste disposal behaviours.

Food Waste Segregation Starter Kit given to households. Source: Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

- An infographic on the types of acceptable and unacceptable food waste was placed on the food waste kitchen caddy as a timely visual reminder for residents to ‘recycle right’ at the point of food waste segregation.

- Residents were given an information kit, which included a handbook and a fridge magnet, highlighting the purpose and impact of food waste segregation and recycling.

- Residents received customised monthly updates on the amount of food waste they recycled, through card letters and their estate’s Facebook group. Drawing attention to their contributions, these messages reinforced the saliency of their efforts, and affirmed their identity as food waste recyclers.

- Fertiliser recycled from the food waste was distributed back to Tampines GreenLace residents. This was a tangible incentive to further encourage residents to participate in food waste segregation.

Example of monthly feedback card on residents' participation. Source: Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

Fertiliser recycled from food waste in Our Tampines Hub. Source: Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

The pilot programme was successful in encouraging at least two-thirds of households who never recycled food waste before to do so at least once. It was also effective in encouraging a third of households to recycle food waste at least once a week.

Contributed by Alice Lee, Environmental Behavioural Sciences and Economics Research Unit, Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

Empowering Individuals to Nudge Themselves and Others

While governments and businesses can shape the external environment and context cues to encourage good habits and sustain behavioural change, they have more limited influence on habit formation in individual homes. Empowering individuals with the ability to nudge themselves as well as others seeks to resolve this.

Self-nudging is an approach that helps people change their behaviour by getting individuals to design their own environments.8 The appeal of self-nudging lies in customising interventions based on individual contexts, which could bring about better results and afford individuals greater autonomy. A 2018 qualitative study by Tormaet al. on driving sustainable consumption behaviour found that self-nudging was effective in helping consumers better align their actions with their intentions to be environmentally friendly.9 When consumers changed from purchasing at supermarkets to preorder organic grocery delivery services, most believed that they made less impulsive decisions due to the lack of context cues in the supermarkets.

One challenge of self-nudging is that it assumes individuals are effective choice architects, meaning that they can (i) assess their behaviours to identify behavioural barriers and enablers; (ii) understand their environment and context; and (ii) design effective nudges. While this seems to imply that only trained behavioural scientists are qualified to self-nudge, it does suggest that individuals need help in designing effective self-nudges. The public sector can play a role in this effort (see box story on How Self-Nudges Can Encourage More Recycling).

Inspiration for such interventions can be taken from how smartphone applications are often designed to help people with their personal habits such as exercising, healthy eating, and taking care of mental wellbeing. Many habit-forming apps make use of behavioural change techniques such as reminders, goal setting, progress tracking, peer support and incentives. However, Stawarz et al. pointed out that many of these apps primarily focus on tracking behaviours, which is not enough to support habit formation.10 Instead, apps could be designed to help users to select trigger events and set reminders to reinforce intentions.11 For instance, users could choose to sort their recyclables (intention) after dinner (trigger event) and choose to receive a daily notification on the application before the trigger event.

The benefit of empowering individuals need not stop at changing one’s own behaviour. A greater impact could be achieved by involving citizens to play an active role in influencing others to adopt green habits. Through this approach, citizens will see themselves as agents of change. There will also be more problem-solvers in society and they might have a better understanding of the behavioural barriers to adopting eco-friendly behaviours. Like self-nudging, the role of the government here is to equip individuals with the necessary know-how to encourage others around them to adopt green habits.

How Self-Nudges Can Encourage More Recycling

While officers from MSE might be expected to be among the savviest about recycling, many of them still express uncertainty on how to recycle right.

To address this, behavioural researchers from the Ministry started a recycling campaign for the Ministry family (MSE, NEA, Singapore’s National Water Agency, PUB, and Singapore Food Agency) called “Sustainability Starts with Me” in 2021. It aimed to empower every officer to be an ambassador for recycling.

“Sustainability Starts with Me” Campaign Logo

The campaign incorporated behavioural elements like simple self-nudges to help officers form common recycling habits such as bagging recyclables to avoid contamination, rinsing drink bottles and cans, and starting a recycling corner.

Participants of the campaign adopted a self-nudge by starting a recycling corner in their homes. The recycling corner was a constant prompt for officers to separate recyclables from non-recyclables. It also made it easier to consolidate their recyclables over time before taking them to the recycling bins.

Example of a Recycling Corner. Source: Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

Another self-nudge that officers adopted was to create a reminder on what can be recycled. Using information from the campaign, these reminders were customised based on what they aimed to recycle, which not only reinforced their recycling knowledge but also enabled the interventions to be targeted to address behaviours specific to their lifestyles.

Example of a Recycling Reminder. Source: Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

These self-nudges helped many officers to recycle more, and to have greater confidence in sharing about recycling with their family and friends.

Contributed by Chng Yee Siang, Environmental Behavioural Sciences and Economics Research Unit, Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

In 2022, behavioural researchers from MSE and NEA will pilot “Eco Avengers UNITE!” with selected primary schools: a programme to nurture students to become effective eco-ambassadors.

Nurturing Young Eco-Ambassadors to Help Others Adopt More Sustainable Behaviours (Eco Avengers Unite!)

In 2022, behavioural researchers from MSE and NEA will pilot “Eco Avengers UNITE!” with selected primary schools: a programme to nurture students to become effective eco-ambassadors. It will equip students to identify sustainability issues in their environment and to create solutions that encourage eco-friendly behaviours in those around them. Students will be taught behavioural insights and design thinking to identify behavioural barriers, and then to design and test interventions to nudge the behaviours of their target audience. As young “Eco Avengers”, students will learn to:

Diagram of the UNITE framework. Source: Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

- Investigate and solve environment challenges using the UNITE (Understand, Ideate, Test, Exhibit) framework tailored to primary school students;

- Identify behavioural motivations and barriers and design targeted interventions using the EAST (Easy, Attractive, Social, Timely) framework developed by the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team (BIT);1 and

- Employ simple data collection methods and controlled trials to understand the problem and test interventions.

In becoming Eco Avengers, students learn to take the initiative to address sustainability issues, without waiting for others to do so.

Contributed by Vivian Lai, Environmental Behavioural Sciences and Economics Research Unit, Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment

NOTE

- Behavioural Insights Team, “EAST: Four Simple Ways to Apply Behavioural Insights”, April 11, 2014, accessed May 19, 2022.

CONCLUSION

Sustaining eco-friendly behaviours is not merely about raising awareness about climate and environmental issues and increasing the adoption of easy habits. But awareness and acceptance do mean that half the battle is won.

Nevertheless, the gap between what we intend to do and how we act must be closed. This will depend on us forming appropriate habits to sustain a change in our day-to-day behaviours. In particular, the challenge is encouraging people to form good but difficult habits (e.g., cutting down on unnecessary car trips, walking or taking public transportation, recycling), and to reduce eco-unfriendly behaviours (e.g., incorrectly identifying materials for recycling).

A greater impact could be achieved by involving citizens in influencing others to adopt green habits.

Because the environment and context affect whether a good habit is formed and/or bad habit is disrupted, the responsibility of habit formation should not fall squarely on individuals. The public and private sectors have roles to play in making it easier for people to adopt eco-friendly habits and to see the value in doing so. Governments could also explore empowering individuals to design their own nudges to form green habits and influence others around them. If implemented properly, these have the potential to achieve more than first intended: individuals can apply the same knowledge to other eco-friendly habits with minimal assistance from governments and businesses.

While these approaches may not be straightforward to implement, they can help ingrain important eco-friendly behaviours for the long term, as part of how we address issues of climate action and environmental sustainability as a society.

NOTES

- Emmanuel Rivière, “Our Planet Issues: Accelerating Behaviour Change for a Sustainable Future”, Kantar Public, accessed May 24, 2022.

- Michaela Barnett, “Good Habits, Bad Habits: A Conversation with Wendy Wood”, October 14, 2019, Behavioral Scientist, accessed May 24, 2022.

- W. Wood, and D. T. Neal, “Healthy through Habit: Interventions for Initiating and Maintaining Health Behaviour Change”, Behavioral Science & Policy 2, no. 1 (2016): 71-83.

- Ibid.

- “How to Recycle."

- Audrey Tan and Mark Cheong, “Recycle-Me-Not: What Happens When the Wrong Things Get Recycled”, The Straits Times, April 18, 2022, accessed May 24, 2022.

- See Note 3.

- S. Reijula, and R. Hertwig, “Self-Nudging and the Citizen Choice Architect”, Behavioural Public Policy 6, no. 1 (2020): 119-149.

- G. Torma, J. Aschemann-Witzel, and J. Thøgersen, “I Nudge Myself: Exploring ‘Self-Nudging’ Strategies to Drive Sustainable Consumption Behaviour”, International Journal of Consumer Studies 42, no. 1 (2018): 141–154.

- Stawarz, Katarzyna, Anna L. Cox, and Ann Blandford, "Beyond Self-Tracking and Reminders: Designing Smartphone Apps that Support Habit Formation", in Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2015), 2653–2662.

- Ibid.