Liveable Density: A Conversation with Heng Chye Kiang

ETHOS Issue 24, August 2022

Why does density matter in urban development and how does it relate to sustainability and liveability?

There are a few different measures of urban density. These include persons per hectare—the number of persons living in one place—and the number of units per hectare, say of dwellings. Other measures include the average plot ratio and site coverage. Now, density of persons per hectare does not tell us what kind of urban form it is. Likewise, dwellings per hectare could refer to very small units: so Hong Kong dwellings may take up very little area, as these are much smaller than housing in Singapore. Plot ratios can give us a rough sense of how much a site is built up, how many storeys there are, but it doesn’t indicate how many people live there: so a 5-room flat could have fewer occupants than a 4-room flat. Therefore, all these different measures are necessary to give a fuller sense of the different aspects of urban density: the urban form, the number of units, and the number of people living on a site and the open space available.

The same density can result in very different kinds of cityscape and urban form. London and Paris are in fact rather dense—equivalent to Singapore’s Orchard Road—but they are very different kinds of cityscape. To an extent, these are the result of different cultural choices, leading to a significant difference in terms of the experience of place. Paris and London are very built-up, with high site coverage of about 70%. There’s little greenery, and any courtyards they have are small. Whereas in Singapore’s HDB, we have lower site coverage, about 40% or less, and there is a lot of greenery, with the positive values associated with this, including heat mitigation, visual relief, psychological wellbeing, and so on.

Different cities have different environmental needs, and this has implications for energy use, such as for heating. So in Singapore’s equatorial climate, we want buildings to have cross-ventilation. In Europe, we hear about heatwaves of merely 32°C causing distress, such as to seniors there. That’s because many of their buildings are not designed to be cross-ventilated, but to retain heat in a cold climate. So when there’s a heatwave, the indoor temperatures keep going up. And in a pandemic, this lack of ventilation in a high-density setting makes things worse. So even with the same density, the way we design at the smaller scale, such as buildings, makes a lot of difference.

Good design makes a given density more liveable than a not-so-good design.

Urban density is related both directly and indirectly to sustainability and liveability. For instance, you need a certain level of density in order for certain kinds of more efficient forms of infrastructure to make sense, such as the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT). But even in terms of basic infrastructure, such as plumbing, low-rise, low density areas differ from high-rise, high density sites.

Of course, we do want more space, and more privacy for ourselves, but it is not necessarily the case that lower density settings offer a better quality of life. Most indices of liveability include components such as safety and security, as well as access to amenities, be it shops, schools, cultural centres or social facilities. You need a certain density to have enough of a catchment area. It’s not even always about economic viability, or infrastructural investment. It is very difficult to have social groups in an area of very low density: it’s harder to form a badminton club or line dancing group with only five families per hectare. You need density for a lot of things to be possible.

What is the right balance to strike, between achieving a practical, sustainable, efficient urban density, and providing a liveable urban environment?

My team carried out a research project to look into this question: what is the threshold of density that we can sustain and afford, while providing a decent quality of life? We looked at about a hundred different typologies across the world, from European-styled courtyard residences to high-rise apartment blocks and their equivalent around the world, and found that the answer to this question is not so straightforward.

One aspect of this has to do with environmental performance parameters. For instance, how much of the sky can you see? If you’re walking in Singapore, you don’t have to lift your head very much to see the sky. If you’re walking in Hong Kong, you’ve got to raise your head more to see the sky, because the buildings are actually taller. In our study, we looked at sky exposure and sky view, and also ventilation and daylight exposure.

Some of these parameters are proxies for energy consumption. For example, the more solar radiation you get, the hotter your interior spaces will be, and therefore the more you need to cool down your building. But then again, the more daylight you have, the less you need to light up the space. You can have buildings, or rather typologies of the same density, in this case plot ratio, performing vastly differently because of the way they are designed.

For instance, the European courtyard typology can have quite poor performance beyond a certain plot ratio, in terms of ventilation, daylight, sky view and so on: all you see is your courtyard or the street in front of your apartment. With the same density, you get much better performance with your HDB tower blocks. So design does matter: at the same plot ratio, good design makes a given density more liveable than a not-so-good design.

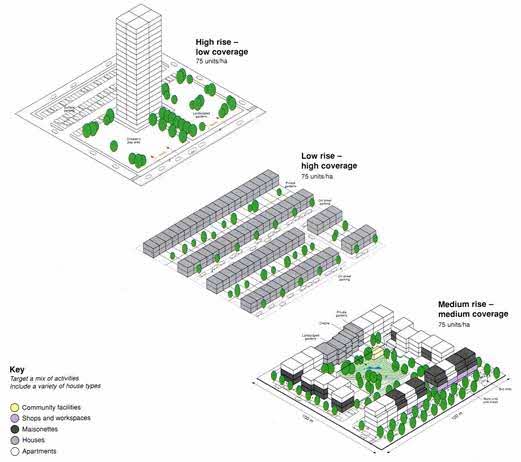

Same Density, Different Urban Form. Source: Andrew Wright Associates1

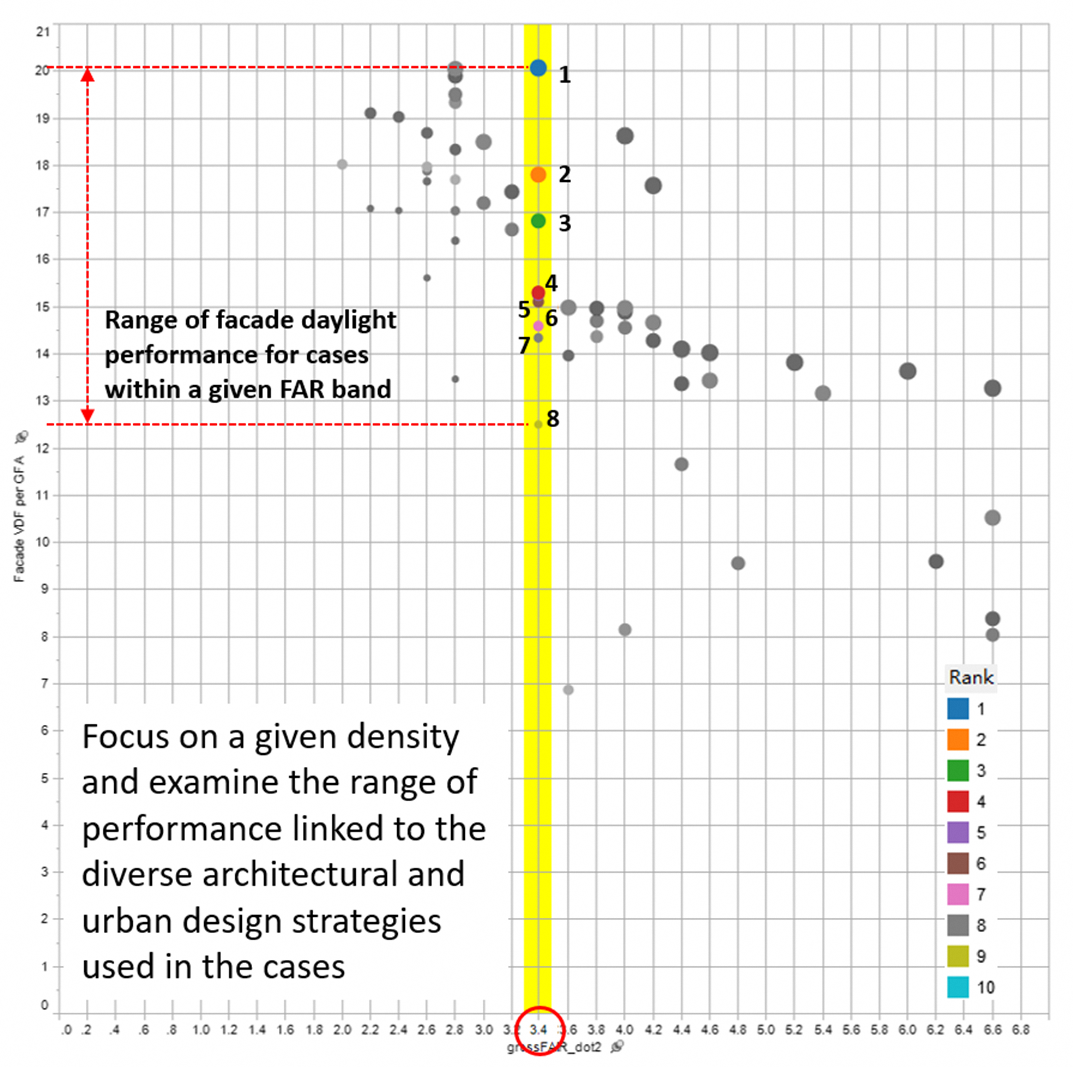

Pareto Ranking for Multidimensional Optimisation. Source: Heng C. K.

To be fair, we have not looked at many examples beyond a certain plot ratio of say 5 and above. In Singapore, a notable example is the Pinnacle@Duxton, which is at a very high plot ratio of 9 or so. But because of its location in Chinatown, surrounded by conserved low-rise properties, Pinnacle@Duxton is still very liveable, because it isn’t obstructed. Density is very contextual. So in our research, we took the Pinnacle and simulated putting it in the middle of a field, as well as in the middle of other similar developments, and the results were very different. The Pinnacle works very well in its current context, but if it is surrounded by eight other Pinnacles, it will work less well.

So there is no one-size-fits-all formula: it is context and an interplay of factors that make a certain density efficient and liveable, or less so?

Density is about the entire environment, and it is not only about a single function. You can see how the different HDB new towns work differently, even though the basic idea of town centres, neighbourhoods and precinct centres, with amenities within walking distance, is quite effective. Based on our research, the residents of these new towns behave quite differently.

In Sengkang, for instance, a resident might shop during the weekends because the nearest shopping centre with broader offerings is a distance away. Whereas people in Clementi shop locally a lot more. Doctors in these mature estates, based at the ground floor of HDB blocks, report that they have more walk-in patients and charge lower fees than the same doctors in clinics located in malls, where the rents are usually higher. So the typologies and distribution of amenities make a difference in resident behaviour.

Planners may also want to bear in mind that particular amenities and spaces may serve very different needs throughout the day. A coffeeshop in a neighbourhood or precinct centre, for instance, may serve residents and nearby workers in the daytime. In the evenings you may get families coming down for dinner. And then later at night, it suddenly becomes a place where mainly older men gather to drink beer and socialise, while the women might be at home watching TV dramas. In the case of 6@Holland, there is even an open space with a tree nearby where some of them might go to smoke from time to time. One French professor I took to see it described it as being like a village square together with a row of first-storey shops. So the coffee shop becomes like a beer garden, a safe place for social gatherings, for a group of people who might otherwise be restless and lacking interaction. Without places like these, mental wellbeing and life satisfaction would go down.

"Village Square" near 6@Holland. Source: Heng C. K.

It is important for us to continue to provide for places like that. For this to happen, a certain density needs to be in place. When we talk about density, we must not forget that it is not just a numbers game. It’s not just about how many people live in a space. It is about how we can make the space into a community, so that people would want to live there, even when they are 70 or 80 years old—not because they have no choice, but because they enjoy living there.

There will be contrarian views: for instance, arguing that people don’t want to live above a coffee shop because there’s noise and smell. But you can design these out. If you anticipate these problems from the start, from the beginning, you can make designs that filter the noise out; you can use technology to help resolve these problems too.

Climate also eventually affects the way we should design: for instance, in Singapore’s climate, it is easy for us to design for outdoor, al fresco dining, even if it takes over some public space.

Bishan Park gets it right, in my view, because they have turned what used to be a mono-functional canal into an asset that not only has infrastructural uses, but also greenery, increased biodiversity, commercial amenities, recreational uses, and so on. It is a solution that addresses multiple objectives and needs at the same time. For us who are planners, we always try to make one plus one more than two.

So the public sector should think across boundaries to consider how to achieve these synergies in planning and multiply their benefits. What should planners bear in mind when doing so?

It is important that whatever amenities we provide should not only be accessible physically, but also accessible economically. For instance, in some of the newer towns, amenities are mostly restricted to shopping malls, where the real estate economics are very different. This changes the balance of what is available to residents and at what prices. From a sustainability point of view, shopping malls are all air-conditioned, compared to say a coffeeshop which is naturally ventilated.

In an estate like Clementi, for instance, there is a mix of uses—the MRT is connected with a smaller mall, with HDB flats above it and the coffeeshops and hawker centres still intact alongside restaurants and cafes. So there are options, other than one big mall that dominates the estate. This mix is also what makes Tanjong Pagar interesting, with its shophouses and HDB flats alongside commercial skyscrapers and some of the most expensive properties in town, as well as an open public space, a park where people can mingle.

Amenities we provide should not only be accessible physically, but also accessible economically.

Culture is always part of the mix, as well as residents’ choices: some people will only have coffee at Starbucks, and others at a coffeeshop, not just because of the cost, but because they prefer it. It is in providing these combinations of possibilities that we get liveability and sustainability within urban density.

NOTE

- Andrew Wright Associates, cited in Urban Task Force, Towards an Urban Renaissance (2002), 35.