Reimagining Productive Longevity

ETHOS Issue 20, Jan 2019

Singapore’s population—and by extension its workforce—is ageing. As the workforce ages, it will also shrink. A tight labour market could negatively affect investment decisions and potentially lead to slower growth.1

Moreover, ageing may also result in slower technological adoption as more age-related health complications reduce worker productivity. The rapid pace of technological progress means that many of today’s jobs may disappear even as new ones get created. As our seniors age, declining cognitive and physical ability may constrain their abilities to take on these jobs.

However, almost half of our seniors remain outside the labour force, despite being in relatively good and fair health.2 The volunteerism rate among seniors is also relatively low at 19%, compared to the national average of 35%, suggesting that there is much potential for greater engagement in productive activity.3

What can be done to enable and encourage longer productive lifespans through changes in policies, job design and work arrangements? How can the public sector take the lead to enhance productive longevity?

What is Productive Longevity?

Productivity is simply the creation of value, which can occur in paid work (as an employee or self-employed person) and also in unpaid work. Examples of unpaid work include volunteering and care-giving, which are not traditionally seen as formal productive work but do add significant value; they may also be alternatives to paid services.

Measurements for productive longevity therefore extend beyond traditional labour market indicators (such as the employment, unemployment and labour force participation rates) to the rate of volunteerism and even Health Adjusted Life Expectancy (HALE).9 Studies have found that a continued state of engagement in paid or unpaid work is good for health: it structures time, creates meaning, gives identity and slows physical and cognitive decline. In other words, health is both a precondition of productivity and also an outcome of productivity.

Research into the ageing issue in Singapore has surfaced four areas of concern:

- Most seniors desire to work longer and delay retirement but do not have the skills and knowledge to access adjacent or new productive opportunities.

- Companies are not always willing or able to employ seniors. This is due to job or workplace designs that are not age-friendly, discriminatory HR policies or the lack of flexible work arrangement provisions.

- Existing information portals and services that supported seniors in discovering new productive opportunities are often under-utilised or not known to them.

- Ageist attitudes persist in society which inhibit seniors from remaining employed or from transiting to new productive opportunities, even when they remain able and willing to work.

Health is both a pre-condition of productivity and also an outcome of productivity.

The Problem of Mismatch, Missed Matches and Mindsets

To tackle the issue of productive longevity, seniors must be able and willing to stay productive. At the same time, companies must offer productive opportunities. These challenges will require changes in the predominant social narrative today, which portrays ageing as a period of deteriorating health, increased dependency and disempowerment.

Three levels of interventions are needed:

First, we need to close the mismatch between seniors and companies. This occurs when seniors are willing and able to work but companies are not willing or able to employ them, and vice versa. We will need to address this by increasing the mastery of both seniors and companies in accessing and providing productive opportunities, respectively.

Second, we need to tackle missed matches. These occur when information asymmetry leads to missed opportunities between seniors and companies, even though there may not be a mismatch of seniors’ capabilities and business requirements. Tackling missed matches will require us to strengthen the ecosystem by tightening coordination efforts across the public, private and people sectors.

Third, we need to confront the ageist mindsets that persist in society. These are reinforced both by explicit anchors (such as the retirement age) and ambient anchors (such as the labels for senior-specific schemes). We need to create a new narrative around what it means to grow old in Singapore.

Information asymmetry leads to missed opportunities between seniors and companies, even though there may not be a mismatch of seniors’ capabilities and business requirements.

Addressing “Mismatch” by Improving Mastery

STRENGTHENING SENIORS’ PRODUCTIVE CAPACITY

Ensuring our seniors remain productive requires us to look beyond the adequacy of tangible assets (such as financial resources) to include intangible assets. There are three categories of intangible assets:

- Vitality assets, such health and well-being, enable seniors to live and work longer with a positive mindset;

- Productive assets, such as skills, expertise, professional networks, enable seniors to remain employable and access new productive opportunities;

- Transformational assets, such as resilience, adaptability, self-awareness, enable seniors to make successful transitions into new areas of opportunity and deal with changes in life or work routines.10

The relatively lower educational attainment of today’s seniors in their earlier years, coupled with the rapid pace of technological developments, means that our seniors need to acquire new productive and transformational assets. In light of this, data from the SkillsFuture credit scheme is encouraging. Of the 285,060 Singaporeans who have used their SkillsFuture credit as of December 2017, 80,604 (28%) are seniors aged 55 to 69 years old.11 This reflects an innate desire among our seniors to continuously upgrade and pick up new skills.

Ageist mindsets are reinforced both by explicit anchors (such as the retirement age) and ambient anchors (such as the labels for senior-specific schemes).

However, there are three challenges. First, there are too many courses, resulting in a “paradox of choice”, whereby the plethora of options induces more anxiety and decision-paralysis rather than empowerment. Second, courses that are work-related are typically not designed for seniors. In fact, fewer than 50% of seniors who enrolled in Workforce Singapore’s (WSG) and Employment Employability Institute’s (e2i) training courses actually completed their training.12 This may be due to the adult training approaches used: many seniors lack “learning how to learn” or meta-cognitive skills, and need a more gradual and guided process to learn effectively. Many seniors also prefer practice-based learning formats rather than formal classroom learning. Third, courses designed for seniors are typically lifestyle- or hobbies-related, without a targeted focus on work and employment.

We should develop course packages customised for different profiles of seniors. These packages should comprise cross-industry hard skills, soft skills and those relating to transformational assets. Instead of a long list of ala carte items, we should design a few set menus with a good balance of the necessary skills to be acquired, curated for different profiles. We will also need to build up expertise and help inject senior-centric pedagogy into the delivery of these courses.

Our seniors also need help to guide them through this life-stage transition. Many may require some support to get their lives in order—i.e., to better understand their employment and learning needs as well as their options, based on a review of their circumstances and aspirations.

We could institute a structured and systematic nationwide outreach programme that invites seniors turning 55 for a holistic life-stage review. This review would cover both their tangible and intangible assets. We have similar life-stage based conversations to help students prepare for the transition to working life. As our seniors’ lives become more complex, a structured life-stage review will be crucial in helping them take stock of their current assets and plan for a meaningful and productive future.

IMPROVING COMPANIES’ CARRYING CAPACITY

Many policies and schemes are already in place to encourage the employment of older workers. These include reduced CPF contribution rates for employers of employees aged 55 and above, the Special Employment Credit scheme which provides a wage offset of up to 8% of monthly wages to employers of older workers, and WorkPro schemes which provide funding to help companies implement age management practices and redesign their workplace processes.13

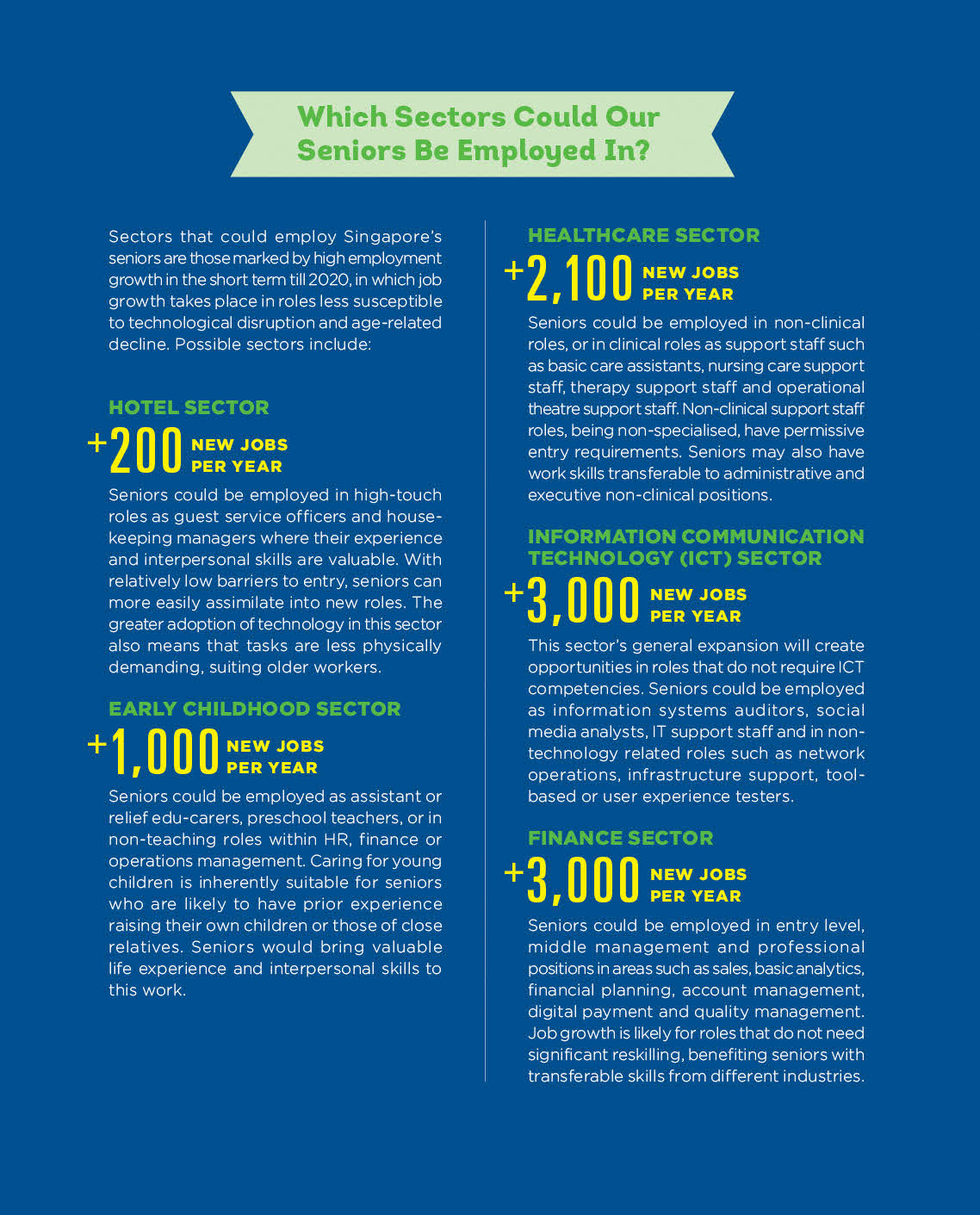

However, many employers still lack the know-how to re-design workplace practices and jobs to make them age-friendly. In addition, although ageing affects the entire workforce, interventions are best made at a sectoral level, to better address sectorspecific challenges to employing seniors. These sector- and industry-wide solutions also allow for greater impact beyond individual companies.

We can develop sector-specific plans to help companies become more age-friendly. The plans should include an assessment of the age- and tech-susceptibility of jobs, the risk of displacement, as well as transition plans for older workers in these jobs. We can consider providing a bonus Dependency Ratio Ceiling (DRC) to those companies in the identified sectors who commit to undertaking restructuring in order to be more age-friendly.14

Ensuring our seniors remain productive requires us to look beyond the adequacy of tangible assets (such as financial resources) to include intangible assets.

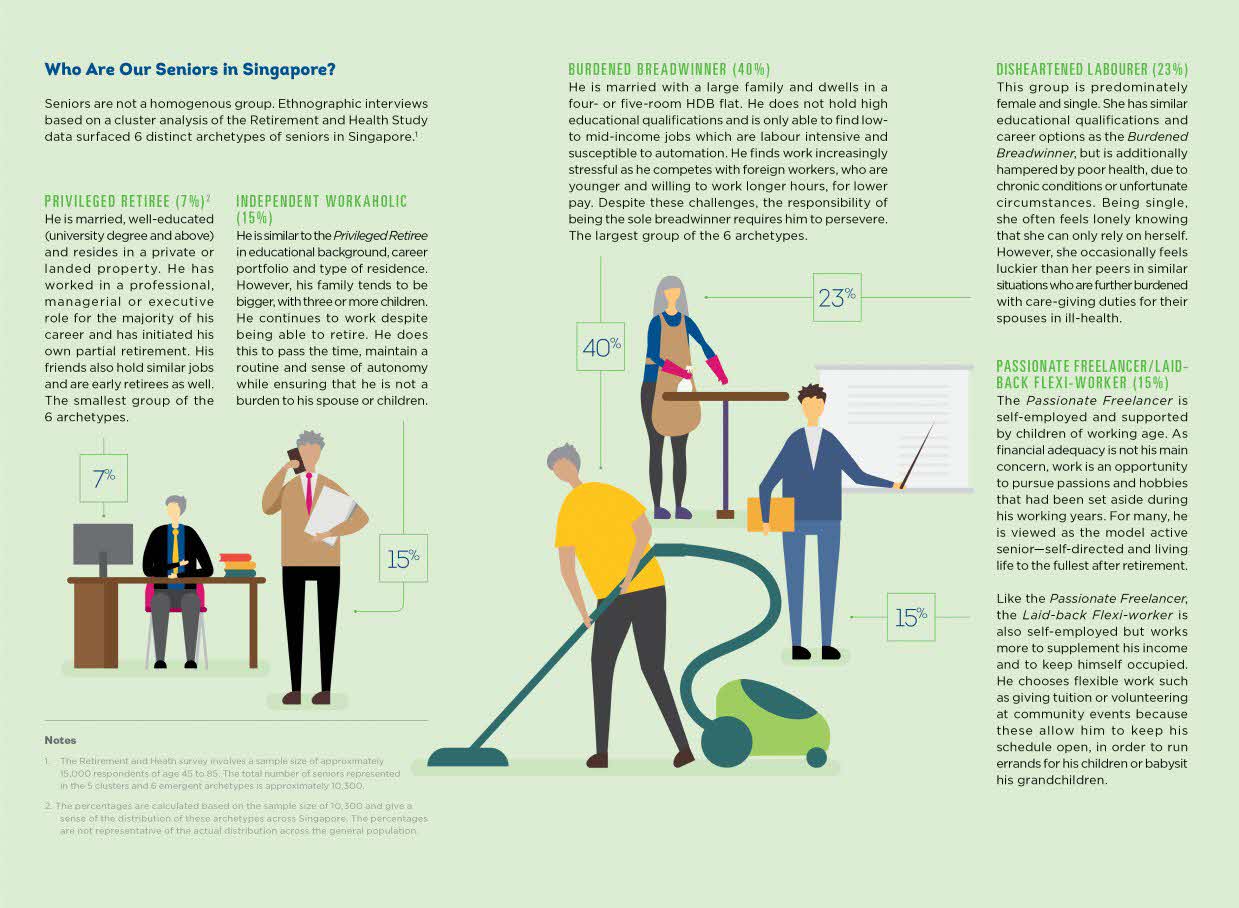

Seniors are not a homogenous group. Ethnographic interviews based on a cluster analysis of the Retirement and Health Study data surfaced 6 distinct archetypes of seniors in Singapore.

The Retirement and Health Study (RHS) is a survey on Singapore residents’ retirement and healthcare needs and how they change over time. Selected individuals are interviewed once every 2 years over a 10-year period. The RHS Board, HDB, MOF, MOH and MOM. The RHS 2014 –2017 data set involved a sample size of about 15,000 respondents of age 45 to 85. The total number of seniors represented in the 6 emergent archetypes was approximately 10,300.

The data was analysed by the data team from Pioneer Generation Office (now known as the Silver Generation Office) and the inter-agency team followed up with ethnographic interviews based on the clusters that emerged from the analysis. The 6 distinct archetypes of seniors in Singapore emerged from the data analysis and ethnographic interviews.

Many employers still lack the knowhow to re-design workplace practices and jobs to make them age-friendly.

OTHER PRODUCTIVE OPPORTUNITIES

While Singapore’s primary approach is to strengthen organisations’ capabilities to provide full or part-time employment to older workers, many seniors remain outside the workforce. Some do so because of ill health or care-giving obligations. However, there is a latent pool of seniors who can make a productive contribution if there are suitable freelancing or volunteering opportunities.

Providing a stipend or allowance to offset the cost of volunteering can potentially draw out seniors who traditionally do not consider volunteering. This could enlarge the available pool of productive labour. Some examples of companies that have tapped on this pool include:

- The Social Iron,15 a social enterprise, has managed to aggregate the supply of seniors who are adept at ironing clothes, to meet demand among busy working professionals.

- Changi Airport Group has demonstrated that providing a small stipend can catalyse seniors to take on volunteer jobs (e.g., Changi Airport Ambassadors) which involve providing a service with a personal touch.

More can be done to generate demand for products or services that tap on the skills that seniors possess. They can serve as tour guides, or front-desk concierge staff, or provide services such as car-pooling, home-based care visits, or usability testing for products and services.

We can provide more support to social enterprises seeking to aggregate demand and supply to create these opportunities. Public sector organisations should be encouraged to create volunteer opportunities by providing a stipend or allowance to offset the cost of participation. If cost-reimbursement is frowned upon for diluting the altruistic motive of volunteering, a national volunteer time bank can be considered instead, where services and skills are exchanged for time instead of money.

More can be done to generate demand for products or services that tap on the skills that seniors possess.

Dealing with “missed matches”

Missed matches between seniors and companies can and do occur, especially with poor information flow. While the current landscape of programmes and schemes to support seniors in their productivity is variegated and comprehensive, national platforms (such as Jobs Bank and Workforce Singapore) are not senior-centric, and senior-centric platforms (such as Centre for Seniors or Silver Spring) lack scale. The fragmented ecosystem poses challenges for navigation and leads to sub-optimal outcomes, with missed opportunities for cross-referral, outreach or joint delivery of services.

We can adopt a more senior-centric approach and devise a coherent strategy across agencies for both paid work and non-paid work. Workforce Singapore could be the lead agency to improve employment outcomes for seniors, working with the Council for Third Age which currently drives senior volunteerism. For a start, they could develop a common framework based on mapping out seniors’ learning, employment and volunteering needs. Common referral processes and the sharing of client data across their network of touch-points will significantly multiply reach and improve programme effectiveness.

Changing Mindsets

Mindsets play a powerful role in supporting or inhibiting productive longevity. Unfortunately, the predominant social narrative today portrays ageing as a period of decline. Media representations of seniors tend to be scarce, inaccurate or framed in disempowering stereotypes.16

One way to shift the narrative is to reshape the citizens’ choice architecture in relation to retirement, which is heavily influenced by the Retirement and Re-employment Act (RRA). The RRA protects older workers from being unfairly dismissed based on age, while balancing competing interests among government, employers and younger workers. By providing a mechanism for resetting job expectations at age 62 while placing a time-bound onus on employers to offer re-employment until age 67, the RRA framework is both worker-friendly and employerfriendly. It provides employment assurance and a socially acceptable mechanism to achieve organisational renewal outcomes.

However, misperceptions of a “retirement age” exist—many perceive it as a mandatory retirement age, instead of a minimum retirement age, and mistakenly feel obliged to retire against their wishes. Furthermore, with increased life expectancy, the raising of the retirement and re-employment age is no longer a matter of should, but of how and when.

We should flip the labels of the two age points: re-label age 62 as the re-employment age and 67 as the minimum retirement age. This better reflects the RRA’s intent and practice, i.e., for employers to offer re-employment at age 62 and to signal to workers that 67 is the current socially acceptable age to leave the workforce. We could also inject some certainty by pegging future increases for these two age-based milestones to an empirical formula based on HALE—an increasingly common practice in other countries.17 Embedding such a formula into existing tripartite consultations could help to depoliticise future age increases and sensitise the population to the necessity of further increases, with rising life expectancy.18

How can we change the narrative by changing the way we talk about ageing? Terminology is key. Even subtle changes in terms and labels used can make a big difference in the public’s mental model of ageing.

At present, the conventional mental frame of life is a three-stage life model: with life progressing in a linear and lockstep manner from education in one’s youth, to work (typically in a single career) in adulthood, and finally retirement in one’s senior years. However, longer lifespans have meant the lengthening of the “work” life-stage to achieve retirement adequacy. This not only creates a physical strain on individuals, but also on systems designed for a shorter work life-stage. Second, digital technologies and economic restructuring are rapidly rendering skills acquired in the early education life-stage obsolete. New short stages of rest and reskilling during the work life-stage are necessary.

We should articulate a new life-stage called the “Third Age” within social discourse, to give structure to the grey zone (i.e., starting from 55 years old) between one’s primary career and full retirement. Naming a life-stage gives it a coherent identity and legitimises its existence. Similar to how the codification of “adolescence” as a distinct life-stage reshaped educators’ and parents’ approach towards teenagers, codifying “Third Age” as a distinct life-stage can do the same to redefine societal norms around ageing.

The “Third Age” life-stage has two defining characteristics. First, it marks a period of intentional reskilling as Third Agers seek to reach further heights in their existing careers, or transit to new careers through actively reskilling. Second, it involves a repurposing of goals and roles as Third Agers tap on their experiences and networks to contribute to their organisations, communities or society in new ways: such as mentoring, care-giving or befriending others.

The focus will be to turn the push (“you have to work longer”) into a pull (“there’s important work you want to do”) and transform the desire to be “free from work” to one of being “free to work”. We should normalise this life stage with new rituals in society: from awarding “Third Age Fellowships” to building up a community of senior social change makers, naming the life-stage conversation as a “Third Age Conversation” and making references to seniors who embraced this transition as “Third Agers”.

The focus will be to transform the desire to be “free from work” to one of being “free to work”.

THE SINGAPORE PUBLIC SERVICE: How to Take the Lead in Enhancing Productive Longevity

As the largest employer in Singapore, the Singapore Public Service has consistently been at the forefront of national efforts to improve employability of older workers. Although the Public Service has a younger workforce than the national average, it is expected to age significantly over time. It should therefore lead the change.

MASTERY

To improve public officers’ mastery—the ability and willingness to work longer—structured transition milestone programmes can be put in place, supported by career conversations for all public officers. The milestone programmes should be designed specifically for public officers aged 50 and above with certain modules that can be customised or curated based on the participants’ profile. The career conversations can happen at age 40, 45 and 50 to give officers a longer runway to build up intangible assets. They can be administered by career counsellors instead of supervisors, to remove the perception that such conversations are linked to appraisals. Comprehensive playbooks and toolkits can be developed to support and guide public agencies in job and workplace redesign.

MATCHING

Mechanisms to facilitate appropriate transitions within and outside the Public Service should be established and enhanced. For transitions into the private sector, “transition dollars and days” can be given to officers to search for new career opportunities. This would help to legitimise job searching during work hours. Greater porosity across agencies could be encouraged via schemes to derisk potential transitions between agencies and encourage the redeployment of officers into new growth areas. Work attachment programmes could be used to facilitate such transitions within the Public Service. Under such a programme, the receiving agency could receive the services of an officer on attachment without utilising its Manpower Management Framework (MMF) headcount during the “trial period”. The Career Transition Unit in the Public Service Division would be key to driving and coordinating these policies while providing centralised support for agencies.

MINDSET

There is a need to reset public officers’ unspoken expectation of an “iron rice bowl”. With technological disruption, the new norm will involve consistent reskilling and redeployment to new roles in and outside public service agencies. This could be supported by a move towards more contract-based employment instead of employment based on the permanent establishment. To incentivise lifelong learning and skills acquisition, a skillsbased component could also be introduced into the wage structure. These shifts would support the new social contract within the Service where opportunities and resources are provided to support “lifetime employability”, instead of an expectation of “lifetime employment”.

Ageing as a Positive Force

That seniors will make up a growing proportion of our population is inevitable. Singapore is neither the first nor only country to grapple with the challenges posed by the confluence of rapid demographic, economic and technological changes. What we have is a valuable opportunity to reimagine what growing old could be like in the next decade and beyond. Ageing does not have to be associated with deteriorating health, disempowerment and dependency. Instead, we can be a society where seniors are empowered, skilled, healthy and active contributors to society. Reimagining productive longevity is a call to reaffirm that Singapore can be, and is, a home for all ages, with opportunities for all.

NOTES

- See: The WEF article (weblink), “How will an ageing population affect the economy?”, Henrique Basso, Economist, Bank of Spain, accessed October, 15, 2017, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/04/how-will-an-ageing-population-affect-the-economy/.

- Source: Labour Force Survey 2016, Ministry of Manpower, MOM.

- National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre (NVPC), “Individual Giving Survey 2016 Results”, accessed August, 12, 2017, https://www.nvpc.org.sg/resources/individual-givingsurvey-2016-findings.

- The Age Susceptibility index (ASI) was developed by Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research. It measures how likely jobholders’ abilities required by an occupation would decline during the working years. This covers both cognitive abilities (e.g., deductive reasoning, memorisation), physical abilities (e.g., explosive strength, manual dexterity), and sensory abilities (e.g., night vision, sound localisation). A total of 954 occupations in the US were ranked and scored, from 0.10 to 99.8. The higher the ASI score of occupation, the more it requires abilities that decline early. The detailed working paper can be accessed at Anek Belbase, Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, and Christopher M. Gillis, “Does Age-Related decline in ability Correspond with Retirement Age?”, working paper, September 2015, https://crr.bc.edu/working-papers/does-age-related-decline-in-ability-correspond-with-retirement-age/ and the index listing can be accessed at http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Susceptibility-Index\_April-2016.pdf.

The Technology Susceptibility index measures how likely the constituent work tasks within a particular occupation are automatable based on current technology. McKinsey Global Institute disaggregated 820 occupations in the US into 2,000 constituent activities and rated each against human performance in 18 capabilities. A tech-susceptibility score of 0.53 means that 53% of the work activities within that occupation are at risk of being replaced by automation. For details, see McKinsey Global Institute, “A Future that Works: Automation, Employment and Productivity”, January 2017. - Between 2004 and 2010, the life expectancy for men increased by 2.1 years, while their healthy years rose by 2.7 years. The change was even greater for women, whose life expectancy rose by 2 years and healthy years by 4. Singapore is ranked third worldwide in average life expectancy at 83.1 years, behind Japan (83.6 years) and Switzerland (83.4 years), but second in healthy life expectancy at 73.9 years, behind Japan (74.9 years). Sources: Ministry of Health, Department of Statistics, accessed at Salma Khalik, “’Healthy Lifespan’ Gets Longer in Singapore”, The Straits Times, December 7, 2015, accessed February 10, 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/healthy-lifespan-gets-longer-in-singapore; World Health Organisation, World Health Statistics Report 2017, accessed February, 10, 2018

- Between 2010 and 2015, seniors aged 55 and above with post-secondary qualifications increased from 17.2% to 22.3%. Source: Department of Statistics Singapore, General Household Survey 2015 (Singapore: Department of Statistics, 2016).

- Between 2010 and 2014, seniors aged 55 and above experienced the highest growth rate of CPF net balances at 90%, almost doubling from $42.1 billion to $79.9 billion. Source: CPF Trends, July 2015, p. 3.

- At 69%, the labour force participation rate for our seniors aged 55 to 64 ranks 8th amongst OECD countries and our unemployment rates rank 6th. Source: OECD Employment Statistics database, data from 1990 to 2016. Accessed January 25, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/employmentdatabase-employment.htm.

- HALE refers to the average number of years that a person can expect to live in “full health” by taking into account years lived in less than full health due to disease and/or injury.

- Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott, The 100 Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016), 71.

- Data accurate as of December 2017. Source: SkillsFuture Singapore.

- Only 676 (45.9%) of the 1,472 seniors aged 55 and above who enrolled in the WSG courses in 2016 completed their training. Source: Workforce Singapore.

- The percentage of an employee’s salary received in CPF contribution is reduced from 37% (ages 35 to 55) to 16.5% for those aged 55 to 65. Employer’s contributions fall from 17% (ages 35 to 55) to 9% (ages 55 to 65). Source: Ministry of Manpower, Committee of Supply-In-Brief, Supplementary Info & FAQs, 2018.

- DRC is a regulatory cap on the proportion of foreign workers that companies can hire. This cap varies by sector.

- See: The Social Iron (website) \[closed since May 2020\]

- United Nations Population Fund, Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge (UN: New York, 2012).

- For example: Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Slovakia.

- In the 1980s, there was no statutory minimum retirement age and the “norm” age at which workers tended to retire was 55. In 1988, the Government set a three-year timeframe to allow employers to voluntarily raise the minimum retirement age to 60 but the uptake was not high. In response, the Retirement Age Act was passed in 1993 to provide a minimum retirement age of 60. In 1999, the Retirement Age Act was amended to extend the minimum retirement age from 60 to 62. In 2012, the Retirement and Re-employment Act came into effect to enable Singaporeans to continue working up to age 65. With effect from July 2017, the re-employment age was raised to 67.