Lifelong Learning & Ageing: Evidence from Singapore

ETHOS Issue 20, Jan 2019

Lifelong Learning and Ageing: Why It Matters

Advancements in technologies and global developments have already mandated a relentless change in the way we live, work, and learn. This means that throughout the course of our lives—even after our initial formal education, throughout our tenure in the workforce, and as we age into our silver years—we have to be prepared to constantly learn and relearn. Learning will no longer be limited to specific life periods and age groups.1

Singapore’s learning imperative, as demonstrated by the SkillsFuture movement, is more than just workforce development: it is also about the attainment of skills mastery, personal development and social integration. As learning becomes lifelong, the participation of our seniors cannot and should not be ignored.

A first attempt to collect data on lifelong learning among adults in Singapore, to assess the current state and future progress of lifelong learning was carried out as part of a 2017 Skills and Learning Study (SLS) by the Institute for Adult Learning (IAL). In this article, we present findings relating to seniors in Singapore aged 50 to 70, indicating their participation, motivation and perceptions of learning.

SLS Findings

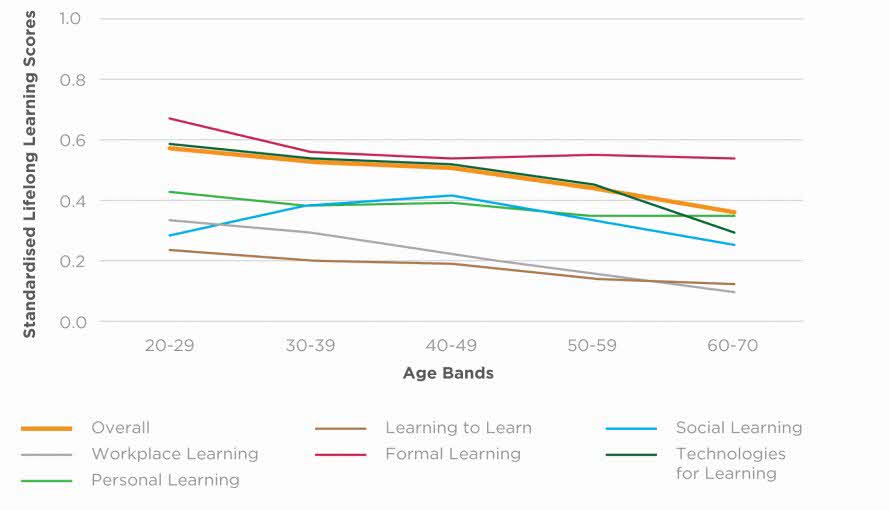

The SLS data suggests that age and education attainment are the two main factors explaining scores across all six pillars of lifelong learning.

LEARNING IS NEGATIVELY ASSOCIATED WITH AGE

Learning is negatively associated with age, even after we take education attainment, employment status, and parents’ education into consideration (see Figure 1). However, within the general decline with age, there are some interesting observations:

- The “social learning” scores peak at the ages of 40 to 49 years old, and the scores for seniors are not that different from 20- to 29-year-olds.

- The “personal learning” scores for seniors are not that different from those of other age groups.

- There is a relatively sharp decline in the “technologies for learning” scores, especially between the ages of 40 to 70 years.

Figure 1. Lifelong Learning Scores, by Age Bands3

While the general decline in learning with age is not unique to Singapore,4 it suggests a potential obstacle in our pursuit of lifelong learning. As we age, our physiological and cognitive functions deteriorate, making it difficult to learn something new.5 This may impede our willingness and ability to participate in learning. Nonetheless, as we confront increased longevity, we have to be more proactive about investing (tangibly or otherwise) in learning during our later years.

We have to be prepared to constantly learn and relearn; learning will no longer be limited to specific life periods and age groups.

In a seminal framework on lifelong learning proposed by Jacques Delors during his tenure as the Head of UNESCO Education Commission between 1993 and 1996, there are four learning pillars: “to know”, “to do”, “to be” and “to live together”. These reflect the modes of learning in relation to formal education, vocational training, personal development, and social cohesion respectively.

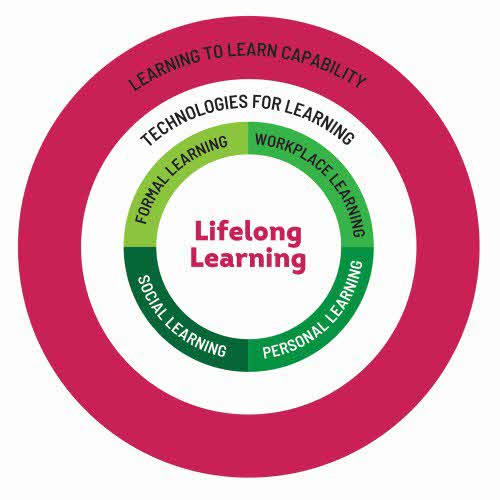

FRAMING OUR RESEARCH: THE SIX PILLARS OF LIFELONG LEARNING

In a seminal framework on lifelonglearning proposed by Jacques Delors1 during his tenure as the Head of UNESCO Education Commission between 1993 and 1996, there are four learning pillars: “to know”, “to do”, “to be” and “to live together”. These reflect the modes of learning in relation to formal education, vocational training, personal development, and social cohesion respectively.2

The Skills and Learning Study retained the original four pillars (renamed “formal learning”, “workplace learning”, “personal learning”, and “social learning”).

Two new enabling pillars were added—“technologies for learning” and “learning to learn”—reflecting important elements that enable the pursuit of learning. The pillar “technologies for learning” relates to the use of the internet and other ICT tools for communication and productivity purposes, to access information, and to carry out learning activities. “Learning to learn” relates to learning strategies and capabilities for self-directed learning.

The Six Pillars of Lifelong Learning

Source: Authors

Table 1. Example of Indicators for the Six Pillars

Each pillar was measured by a basket of indicators relating to learning participation, motivation and perceptions, which were combined to form a pillar learning score.

Notes

- Jacques Delors et al., Learning: The Treasure Within. Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century (Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1996).

- As an “experiment” prior to the Skills and Learning Study (SLS) 2017, we used this framework and data from the PIAAC study to create an international lifelong learning comparison. See: J. Sung and S. Freebody, “Lifelong Learning in Singapore: Where are We?”, Asia Pacific Journal of Education 37, no. 4 (2017): 615–628.

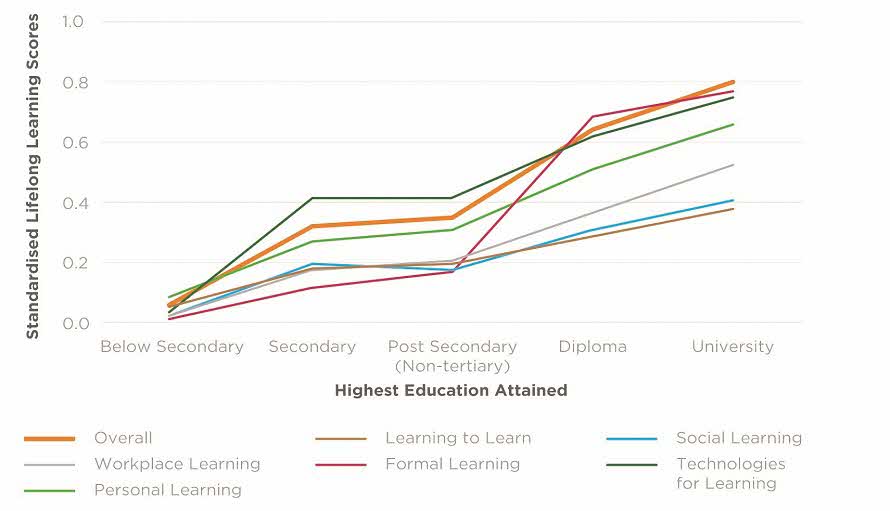

LEARNING IS POSITIVELY ASSOCIATED WITH EDUCATION ATTAINMENT

Learning is positively associated with education attainment, even after we take age, employment status, and parents’ education into consideration (see Figure 2).

- The education effect is most evident in the “technologies for learning” score. In particular, the difference in scores between the group with “below secondary” education and the group in the next category is rather large.

- The incline in scores for “social learning” and “learning to learn” is relatively less steep.

This suggests that participation in lifelong learning is significantly influenced by previous education and learning experiences.7 However, lifelong learning is important to consider in relation to social inclusion and cohesiveness. We therefore have to be more conscientious about reaching out to seniors from all walks of life, so that everyone can benefit from lifelong learning regardless of their backgrounds.

We have to be more proactive about investing in learning— tangibly or otherwise—during our later years.

Figure 2. Lifelong Learning Scores, by Highest Education Attained6

“NO TIME” TO LEARN?

Although learning is crucial to ageing successfully and actively, learning participation among seniors is low compared to other age groups. Among seniors who indicated in our study that they had not participated in any education or training in the preceding 12 months, slightly more than 1 in 2 (52.2%) picked “lack of time” as the most important reason for their lack of participation. This seems to contradict conventional wisdom that older folks have more time, especially those who have retired.

CONFIDENCE IN OWN ABILITIES MATTERS

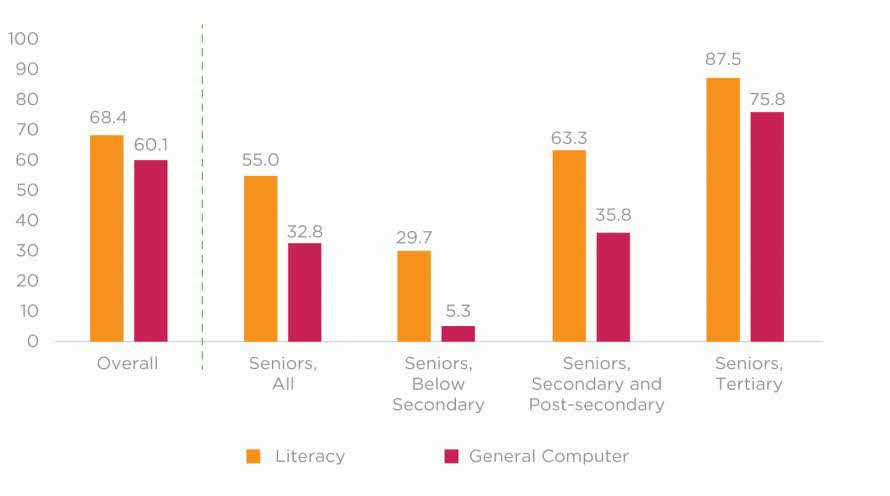

Our data shows that learning is positively associated with a person’s confidence in his or her own abilities, even after we control for the effects of age and education attainment. As seniors learn and adapt to technological advancements and global developments, confidence in their own literacy and computer skills are important prerequisites that support further learning efforts.

However, we found very low levels of skills confidence among seniors with less than secondary education. Among this group of respondents, only 3 in 10 were confident in their literacy skills, and just 1 in 20 were confident in their computer skills. This was in sharp contrast with respondents in other age groups and education levels (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Seniors’ Self-assessed Confidence in Their Own Literacy and Computer Skills

Participation in lifelong learning is significantly influenced by previous education and learning experiences.

ENABLING LIFELONG LEARNING

We took “technologies for learning” and “learning to learn” to be enablers in pursuing learning. Using our data, we tested the correlation between these two enabling pillars, and the other learning pillars, and found a modest to strong positive correlation, especially among seniors. Among non-seniors, the same relationship also occurred, although it was relatively weaker.

This suggests that to help our seniors with lifelong learning, we could look into harnessing technologies for learning and enhancing their ability in learning to learn, as these will help strengthen their overall capability to learn other skills.

A Learning Society for All Ages

When we talk about successful and active ageing, we want our seniors to be empowered individuals, knowledgeable and contributors at work, and to be valued members in their community. This goal does not come without its own set of challenges and many are inter-related. It is crucial that we acquire a good sense of how seniors can learn, and support them in developing passion and confidence to seize any new learning opportunities they are given.

With the push to encourage lifelong learning through various initiatives of the SkillsFuture movement, we would expect to see changes in the patterns for lifelong learning over time. Therefore, it will be of our interest to track these changes in the next iteration of the Skills and Learning Study.

NOTES

- Jacques Delors et al., Learning: The Treasure Within. Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century (Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1996).

- Our data on lifelong learning was collected as part of the Skills and Learning Study (SLS) 2017 conducted by IAL. The SLS 2017 is the second iteration of a skills study covering a range of skills topics including skills utilisation, job quality, qualification and skills mismatch, and the gig economy. This latest iteration has also been expanded to include the lifelong learning component. The study is constructed as a national random sample survey, covering a representative sample of Singapore residents of age 20 to 70 years old. Data collection for this iteration of the survey took place from July 2017 to March 2018.

- The learning scores presented in Figures 1 and 2 are based on the standardised regression coefficient. Rather than the value of the score, we wish to draw attention to the size of the differences in age bands (or education levels) between the six pillars.

- For example, similar trends were observed in the UK. See: Foresight, Future of Skills and Lifelong Learning (London, UK: Foresight, Government Office for Science, 2017).

- E. Stine-Morrow and J. Parisi, “The Adult Development of Cognition and Learning”, in Adult Learning and Education, K. Rubenson (Academic Press, 2011), 41–46.

- We should make a note that the sharp increase in scores in “formal learning” between the group with post-secondary (non-tertiary) education and that with diploma education is likely due to how we have constructed our pillar. One of the indicators that we have included in the “formal learning” pillar is the attainment of tertiary education.

- S. Gorard, “The Potential Lifelong Impact of Schooling”, in The Routledge International Handbook of Lifelong Learning, ed. P. Jarvis (London: Routledge, 2009), 91–101.