Using Data to Create Better Government

ETHOS Issue 16, Dec 2016

Technology has drastically shifted our ability to capture and analyse data. In recent decades the capability that has come to be known as big data analytics has evolved rapidly. While big data was originally viewed narrowly as a means for retailers to understand their customers better, insights drawn from collecting and analysing data can now deliver benefits across an expanding range of services. The impact of big data is being felt in corporations, governments, and even individual households. It has been applied in a wide range of activities, from remote monitoring of off-shore oil rigs to tracking health metrics using personal fitness bands.

Governments that harness this power can optimise use of resources, improve citizen and business satisfaction, and create more accurate predictions of future needs. Big data analytics could help governments develop insights from a cascade of information that may significantly improve public sector performance at all levels, from municipal to national.

COMING OF AGE

Big data is growing. The International Data Corporation estimates that the amount of data collected and stored worldwide will expand tenfold between 2013 and 2020, from 4.4 zettabytes to 44 zettabytes. (For scale, The Economist noted that 1 zettabyte is equal to 142 million years of high-definition video.) Part of this imminent data explosion will be driven by wide-scale use of connected devices, often referred to as the Internet of Things (IoT). The number of connected devices is expected to increase from 10 billion in 2013 to 50 billion by 2020.1 Many of these devices will be linked to smart-city programs, such as sensors embedded in streets and other public areas. By 2020, smart-city initiatives in Europe will generate 100 exabytes (or one tenth of a zettabyte) of data daily, four times more than the global data generated daily from all usages in 2015.2

New technology and techniques — such as the IoT, advanced machine learning, and artificial intelligence — are amplifying our ability to collect, distribute, and analyse data. At the same time, new tools, such as data visualisation applications, are making it easier for governments, businesses and others to understand and respond to the insights delivered from the analysis.

Governments are well positioned to benefit from this coming of age. In particular, they can use big data analytics to trigger improvements across three broad areas:

- Resource optimisation: Cost savings can be achieved by using data to eliminate waste and direct resources more effectively. One powerful example of this is better management of human resources. Using data analytics, one US federal agency halved its staff attrition rates and saved more than US$200 million in the first year, by eliminating retention programmes that it found had no real impact and focusing instead on more effective programmes.

- Tax collection: Governments can identify and stop revenue leaks, especially in tax collections. The Australian tax authority analysed more than one million archived tax returns from small- and mid-sized businesses and identified groups with a high risk of underreporting. Targeted reminders and notices increased reported taxable income by more than 65% within those groups.

- Forecasting and predicting: Big data analysis can help governments understand ongoing trends and predict where resources are needed. For instance, the Los Angeles police department has used a predictive analytics system to comb through data such as historic and recent criminal activity, predicting where and when specific crimes might occur and dispatching officers accordingly. One study suggests the system is twice as accurate in predicting crime as traditional methods.3

SMART WATER MANAGEMENT

The UK water distribution company Southern Water deployed smart water meters providing utilities, property managers and users with real-time data on water usage. Smart meters can reduce operating expenses, for instance, by automatically locating costly leaks and eliminating the need for manual meter readings. Smart meters were installed for 90% of the utility’s customers, contributing to a 17% drop in water use. In Southampton alone, smart meters saved an average of 5.3 million litres of water a day.

Governments already collect vast amounts of macroeconomic and individual data that can form the basis for a strong database reaching across industries and public agencies.

THE TWO SIDES OF DATA ANALYTICS AND GOVERNMENT

Governments have two complementary roles to play in using big data analytics to deliver better and more efficient public services. The first is using data to shape those services, and the second is to use the state’s authority and reach to build an integrated ecosystem of data collection and use.

Using data to inform and guide public services is perhaps the most common first step by governments. Generally, public authorities start with efforts most likely to generate early wins and demonstrate the value of such new initiatives. For example, London’s Citymapper app for mobile devices uses data such as maps, real-time congestion information, rail and bus timetables to offer optimal routes to commuters, cyclists, and pedestrians. Time saved by such apps in London is estimated to be worth about US$150 million yearly.4

These early wins can set the stage for bolder commitments and strategies. Chicago, for example, announced a Tech Plan in 2013 that aspires to use data analysis and other new technologies for improvements across all municipal departments. Among other aspects, the plan states that “data-driven decision-making is helping the city reduce costs and offer services better tailored to public need… Using data science to continually improve and streamline government processes is one way to emphasise and strengthen Chicago’s position as a leading global technology hub.”5

Beyond collecting and analysing data, governments also have the mandate and scale to shape the overall data ecosystem, creating a large and transparent repository that benefits the public and private sectors. Governments already collect vast amounts of macroeconomic and individual data that can form the basis for a strong database reaching across industries and public agencies. The growth of smart-city initiatives and programs will continue to build on this arsenal. To encourage the development of a data ecosystem with broad benefits, governments should provide standards and regulations to shape data sets that can be read and used widely.

Governments have a unique role in creating institutions and developing at scale the capabilities needed to generate useful insights from the flood of data. They can also expand the benefits of making data sets — with tight privacy safeguards — broadly available, giving the public the opportunity to create, collect, manage, and analyse data for their own purposes. For example, France and the United Kingdom have explicitly stated that data should be open by default. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that more than US$3 trillion in value can be created annually with open access to such data.

PROTECTING PRIVACY AND PERSONAL DATA

Global market surveys have shown that citizens are concerned about their privacy: many fear personal data may be compromised and misused with the advent of big data analytics. As part of the effort to shape the volume and texture of data collected, governments must credibly assure individuals and corporations that all data collected and handled will be protected vigorously and not susceptible to manipulation or unauthorised access.

Governments can build the necessary trust to promote a good data ecosystem in several important ways. First, they must develop a comprehensive legal framework to protect personal and sensitive data, including clear and effective repercussions in the event of any compromise. Estonia’s data management is exemplary in this regard. If there is private data that the state cannot legally be prevented from seeing, affected citizens can at least get a record of who viewed their data and when. They can also file an official inquiry if they find that such access is not justified.1

Second, governments should invest in data systems that prevent intrusions but allow efficient access to authorised users. Third, effective processes must be in place to assure that open data is anonymous, cannot be linked to individuals, and doesn’t contain identifying information. In particular, an intrusion in one data set should not compromise personal data in others. Finally these measures must be communicated clearly to the public to allay lingering concerns.

Notes

MORE THAN JUST DATA

Many corporations and governments struggle to implement a big data programme that can capture the full potential of these new technologies. To ease this burden, governments must craft a deliberate approach to data analytics that considers current and future needs.

Using insights gleaned from data to inform decisions and guide policy can be a radical departure for organisations that have traditionally relied on personal knowledge and, at times, instinct. However, real power will be unleashed when analytics-based approaches become deeply embedded in government culture, with data-based predictions and prescriptions shaping the government’s core strategies.

While data is obviously a key aspect of such programmes, three other factors also carry significant weight: strategy, people, and organisation. A comprehensive programme that considers all four aspects has the greatest chance of delivering the full benefits of big data analytics.

Strategy

Businesses and governments are often enticed by the allure of big data and launch initiatives without a clear strategy to guide them. Analytics for its own sake will struggle to deliver on its promise. Instead, organisations must formulate a clear strategy based on an understanding of the likely benefits, with clear and measurable targets and the support of top leadership.

A healthy start would be to focus on use cases, with individual applications designed to deliver a specific result. Choosing use cases that produce obvious benefits for citizens, from structured and clean data that is readily available and is supported by key stakeholders, can often deliver quick wins. By building a strategy around use cases, governments help assure that the benefits captured align with public policy and priorities.

In Singapore, for example, one use case has centred on better home-based monitoring of the elderly.6 One system implemented uses wireless sensors to track the activities and health of the elderly in their homes and can alert caregivers to any anomaly. The system is supported by an application that is easy to launch, features large font sizes and contrasting colours, and includes a text-to-speech function, reducing the need to type. The application is embedded in devices sold to the elderly. The system offers a safe and less expensive alternative to retirement homes and community-based care.

As part of overall strategy, governments may also have to re-examine a monolithic approach to data security. Not all data is sensitive or poses a privacy concern, and governments should consider ways to allow access to non-sensitive data to enable its use more broadly.

In one approach, the United Kingdom has classified data under three security tiers, with the lowest, most open tier containing the vast majority of the information it collects. While data in top two tiers remains subject to stringent controls and is accessible only by the government, data in the lowest tier is protected using a commercial threat model similar to that used by commercial banks.7

Using commercial solutions eliminates the need for custom security controls and systems and allows governments to consider less-expensive cloud-based solutions. This also allows agencies to adopt different solutions based on their individual needs. For example, HM Revenue & Customs agency deployed Microsoft Surface Pro and a customised set of Google Apps for its staff.

The UK approach to opening up data access extends beyond the public sector. In London, for instance, the Datastore system aggregates data sets from public and private sources and makes them available publicly.

Data

Raw, unorganised data, collected and stored almost randomly, is difficult to use effectively. Governments should build comprehensive data sets that are granular, standardised, and machine-readable, and that protect anonymity.

Analytics for its own sake will struggle to deliver on its promise. Instead, organisations must formulate a clear strategy based on an understanding of the likely benefits, with clear and measurable targets and the support of top leadership.

For example, governments should collect transaction-level data that can be used flexibly based on individual use cases, rather than rely on broad summaries of activity. In Singapore, the Land Transport Authority collects individual, anonymous data on each transaction, including the time, beginning, and end of a trip. The data collected has proven useful in helping to identify new direct transportation routes that commuters may wish to have, for example, to get to work every morning. This information has been fed into a digital mobility platform called Beeline, developed by the Government Technology Agency, which helps match commuters’ demand for new travel routes with supply by private bus operators.8

Also, governments must ensure that data is shared appropriately among public agencies, breaking silos that can hinder success. Estonia, which The Atlantic magazine has called “the world’s most tech-savvy government,”9 has established the X-Road system, a service-oriented architecture that eases communications among public and private databases. In 2013, more than 170 databases were connected to the system, with more than 2,000 services offered. More than 900 organisations used it daily.

Behind functional capabilities, governments should develop a culture that is conducive to digital innovation and which attracts the best talent.

People

Using big data analytics is a change from traditional operating practices, and civil servants at all levels must understand the benefits of the program and support it. In New Zealand,10 the government offered a digital and analytics masterclass to more than 70 senior administrators to present the fundamentals of big data analysis and other aspects of new technology, such as the agile methodology and design approaches. Similarly, San Francisco established a Data Academy programme to train city officials and workers and build capabilities.11

Behind functional capabilities, governments should develop a culture that is conducive to digital innovation and which attracts the best talent. Israel used experience from its military training programme to create a talent development kit that helped attract recruits with strong engineering and digital skills.12 The UK’s Government Digital Service, working under the motto “We are revolutionising government”, has created a decidedly non-bureaucratic work environment with distinctive locations and programming events such as “hackathons” to identify potential recruits.13

Organisation

Organisational changes will probably also be needed to create a strong data ecosystem that spans government agencies. One successful model is to establish a centre of excellence for big data analytics that works across agencies and is responsible for aggregating and bundling data and championing its use.

In 2013, New York created the Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics to drive change across city agencies.14 The six-person office collaborates with agencies to improve service delivery using data, managing the internal data sharing platform, DataBridge, and the public platform, NYC OpenData. It also implements special city data initiatives, such as disaster response and resiliency efforts, and develops capabilities among city agencies through training programmes.

SINGAPORE: A SMART NATION BUILT ON DATA

As part of its Smart Nation initiative, Singapore is building a nationwide infrastructure to enable better sensing of how the city works, and to optimise the running of smart city services. Singapore is putting in place systems to collect data, perform analytics to interpret real-time data as far as possible, and ultimately, to visualise insights to help public agencies make better planning decisions, and enhance their operations.

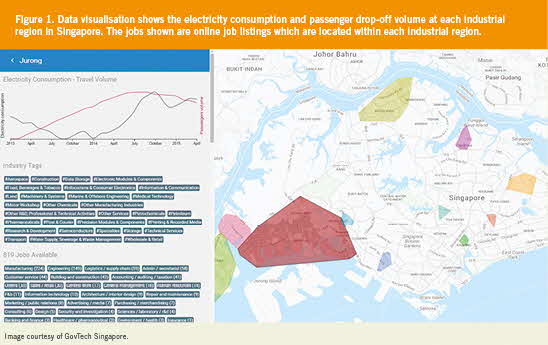

For example, the GovTech’s Data Science team, in collaboration with various government economic agencies, is working on an initiative called the Pulse of the Economy that looks at high-frequency big data, including electricity consumption, public transport, online job listings and other urban data sources, to develop new indicators for better economic and urban planning.1

Traditional economic indicators such as GDP and Employment take a longer time to gather. With Pulse of the Economy, real-time big data sources can be merged to create a richer picture of the state of the economy, offering early warning signals for intervention with more detail in terms of location and sectors. For example, the amount of electricity consumed in a particular industrial region in Singapore and the number of people alighting at bus stops in the region can provide a timely indicator of how much economic activity is happening there (see Figure 1).

As more meaningful big data sources become available, new ways of improving people’s lives will become possible. For example, we can use crowd density data to understand how people commute and access key social amenities (for example, parks, healthcare, places of worship), and thus improve the distribution and accessibility of these amenities. Similarly, better data could improve transport modelling to relieve congestion and enhance public transport options.

— GovTech Singapore

Image courtesy of GovTech Singapore.

Notes

CONCLUSION

Governments at all levels are charged with delivering the best services to their constituencies from available resources. Whether municipal, regional, or national, governments can draw significant benefits from big data analytics. Resources can be used more efficiently, citizens served more effectively, and plans developed with a more accurate vision of the future. To achieve success, governments must develop a clear strategy, understand the nature of data, ensure they have built the right capacities, and develop organisations that are fit-for-purpose within a healthy data ecosystem.

NOTES

- World Economic Forum, “Is this the future of the Internet of Things?”, http://www.weforum.org.

- Cisco Global Cloud Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2014–2019 White Paper, http://www.cisco.com.

- City A.M., “Open data: London is streets ahead when it comes to helping commuters plan their journey — but we mustn’t become complacent”.

- Source: Housing & Development Board, “My Smart HDB Home @ Yuhua”

- Source: UK Government, “Government Security Classifications, April 2014”

- https://govinsider.asia/smart-gov/exclusive-singapores-radical-new-transport-plan/

- The Atlantic, “Lessons from the World’s Most Tech-Savvy Government”.

- https://www.digital.govt.nz/.

- https://datasf.org/academy/ .

- http://www.timesofisrael.com/for-hack-contest-winners-a-ticket-into-unit-8200/.

- https://gds.blog.gov.uk/2015/10/09/how-to-be-agile-in-a-non-agile-environment/.

- Governing, “How New York City Is Mainstreaming Data-Driven Governance”.