Lessons from New Zealand’s Better Public Services Reforms

ETHOS Issue 16, Dec 2016

INTRODUCTION

From 2011 to 2015, the New Zealand public management system underwent a significant overhaul of its legislation, policy and financial settings, incentives, decision-rights and approaches to governance. These Better Public Services reforms sought to address poor outcomes on complex cross-agency issues and to modernise service delivery in response to changing citizen expectations.1 The reforms have now shifted from a period of enabling change to ongoing implementation. The phase of enabling change offers practical lessons about what it takes to sustain significant reform.

WHY THE BETTER PUBLIC SERVICES REFORMS ARE INTERESTING

New Zealand’s last wave of radical reforms in the 1980s drew international attention for signalling a paradigm shift from the long ascendance of Public Administration to the rise of New Public Management.2 New Zealand went further and faster than other jurisdictions in instilling corporate discipline on government agencies through sharp accountability matched with strong agency autonomy to marshal and compete for the resources to deliver on their outputs.

This focus on accountability, autonomy and competition cultivated an environment in which individual agency performance was incentivised, but cross-agency cooperation was not. On complex cross-agency issues it is difficult to align and integrate finances, resources and decision-rights. The easier, more rewarded path was to go it alone on one part of the problem rather than struggle through the uncertainty and difficulty of working across agency boundaries. The Better Public Services reforms address the strengths and weaknesses of the radical shift to New Public Management, marking a further paradigm shift towards New Public Governance.3 In a complex and rapidly changing world there is a global demand for public services that are citizen-centred, flexible-at-pace and capable of networking and working with partners in the private and non-governmental sectors. New Zealand’s reforms are notable for focusing on achieving financially sustainable performance improvements through delivering complex medium- and long-term results, in a period where many jurisdictions turned to austerity as a lever of change.

Without responsiveness to political decision makers and citizens, the civil service is not serving

While not heralded with the triumphant, reformist zeal of New Public Management in 1987,4 the Better Public Services reforms represent an organic attempt to put the still developing theory of New Public Governance into action.

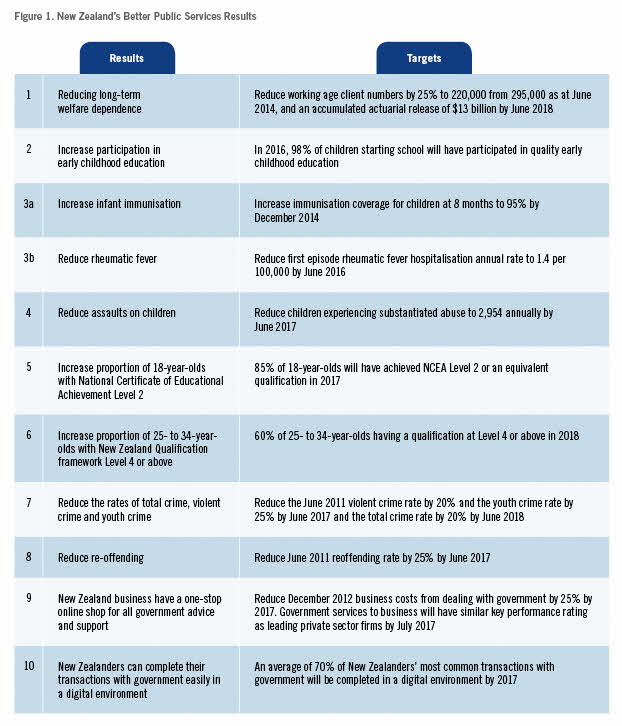

Figure 1. New Zealand's Better Public Services Results.

The Public Management Toolkit

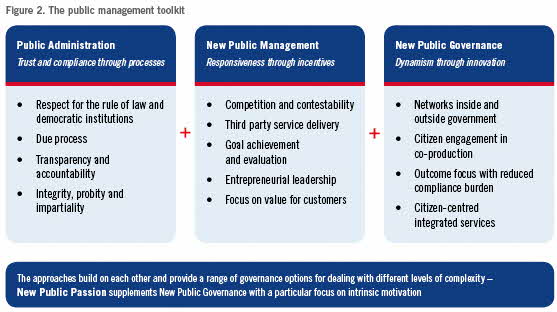

Figure 2. The public management toolkit.

Figure 2 draws on Stephen Osborne’s discussion of the three regimes to make the case that Public Administration, New Public Management and New Public Governance build on each other and provide a range of governance options for dealing with different levels of complexity.1

The values established by Public Administration remain the lifeblood of an effective civil service. Integrity, professionalism, merit-based appointment and political neutrality take different forms in different contexts, but a clear and consistent approach to these issues is foundational, and builds critical trust. However, those core values are often channelled into routine compliance activities where the enforcement of rules and the tyranny of process supersede real service to citizens. The primary motivation becomes one of compliance or, even worse, of self-preservation in the face of the forces of change. If change is accelerating and the civil service is rigid rather than adaptable, responsiveness is bound to suffer. Without responsiveness to political decision makers and citizens, the civil service is not serving.

New Public Management addresses shortcomings in responsiveness through a central focus on accountability. What gets measured, gets done — and, if accountability for delivery is clearly assigned and incentives for performance aligned, then responsiveness will follow. As a result, New Public Management tends to favour competition and clarity of focus over collaboration and joint responsibility. Sharp accountability can drive high levels of responsiveness on complicated issues, but not necessarily the stewardship and dynamism required to ensure long-term delivery on complex issues where sole accountability cannot be assigned.2

New Public Management is a powerful tool for improving performance, but struggles to provide a framework for effectively addressing rapid change in a complex interdependent environment. New Public Governance seeks to address this by harnessing networks inside and outside of government to enable dynamic responses to complex issues. It emphasises an outcome focus with a reduced compliance burden, the integration of citizen services, and citizen engagement in the coproduction of services.3 New Zealand’s Better Public Services reforms reflect the shift towards New Public Governance in the 2010s.

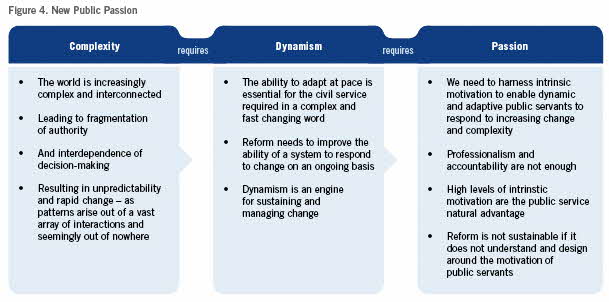

In environments where the public discourse on bureaucracy is focused on waste- and cost-cutting, however, attempts to implement New Public Governance-style reforms may still rely on extrinsic incentives, rather than intrinsic motivation, to drive change. Decades of New Public Management practices can also make it challenging for institutions and leaders to harness intrinsic motivation beyond the boundaries of an individual agency — as was the case in New Zealand. Yet successful reform depends the performance of civil servants, and sustained performance depends on their engagement and motivation. High levels of intrinsic motivation are the public service’s natural advantage, but that advantage needs to be encouraged and stewarded or it is lost. New Public Passion is an attempt to bridge the motivational gap and sustain dynamism in a complex and rapidly changing environment.

NOTES

- Stephen P. Osborne, The New Public Governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2010).

- Better Public Services Advisory Group Report (PDF,1,005KB) (New Zealand Government, November 2011).

- See note 1.

KEY FEATURES OF THE BETTER PUBLIC SERVICES REFORMS

The key features of New Zealand’s Better Public Services Reforms include:

Results

- A results-based approach: the Prime Minister’s 10 Better Public Services Results for New Zealanders is a focused selection of complex cross-agency issues given clear 5-year targets, individual and collective Ministerial and Chief Executive accountability and 6-monthly public-facing reports on progress.5

- Legislative change to the State Sector Act6, Public Finance Act7 and Crown Entities Act8 to remove perceived barriers to cross-agency work and enable flexibility.

- Strengthened cross-agency governance and funding arrangements to allow collective decision-making and action.9

- Mobilising capability and information across agency boundaries, including whole-of-government “big data” through the Integrated Data Infrastructure.10

Stewardship

- Redefining the Chief Executive’s11 legislated role to include stewardship over departmental wellbeing and the collective interests of government, with matching incentives and indicators for cross-agency performance.12

- An integrated Four Year Plan that brings together strategic, financial, human resources and ICT demands, replacing fragmented departmental plans and reports.13

- Aligning independent and public-facing reviews of agency performance with the requirements of reform.14

System leadership

- A new Cabinet-mandated Head of State Services role for the State Services Commissioner, accountable for the overall performance and stewardship of the State services and for bringing together Chief Executives to collectively advise Government on further systemic change.3

- Significant strengthening of cross-agency powers for ICT, property and procurement, improving effectiveness and efficiency in major areas of government investment with collective implications.16

KEY LESSONS FROM THE BPS REFORMS

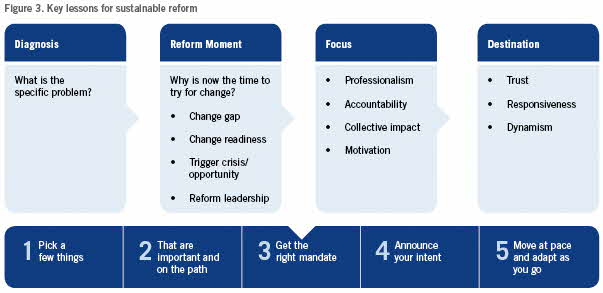

As outlined in Figure 3,17 New Zealand’s Better Services Reform experience offers three key lessons for sustaining reform: (i) the features of a ripe Reform Moment; (ii) the critical importance of selective focus in creating change momentum; and (iii) the risks of underestimating intrinsic motivation as a driver of public service, performance and change.

Figure 3. Key lessons for sustainable reforms.

The Reform Moment

The Better Public Services Reforms were not the first attempt at mitigating the shortcomings of New Public Management. The diagnosis of prioritising accountability over the ability of agencies to work together where required had long been established – from as early as the Schick Report of 1996.18 Initiatives between the late 1990s to the late 2000s had all made significant efforts to adjust this balance, with limited returns.

The relative success of the Better Public Services reform effort indicates the importance of the Reform Moment. Four features made 2010-11 particularly auspicious for reform in New Zealand:

- Change gap — The context for the New Zealand State services had clearly changed since the reform of the 1980s. ICT, globalisation and the rise of the non-governmental sector had increased complexity and the pace of change. Changing citizen expectations demanded a change in public sector service delivery.

- Change readiness — No system can successfully constantly reform. The passage of time from one period of intense reform to another is important for renewing energy and acceptance for the need to change. The two decades since the last major reforms had given sufficient time for the shock of that reform to pass, the gains to be realised and the weaknesses to be clear.

- Trigger crisis or opportunity — New Zealand was partially insulated from the effects of the 2009 Global Financial Crisis, but it still led to a shift from surplus to deficit and a need to tighten government expenditure. The move to cap agency funding baselines and staff numbers forced government to reconsider how to deliver improved citizen-centred services at reduced cost. It chose to focus on delivering savings through improved results rather than simply pursuing cost-cutting and austerity.

- Reform leadership — Bill English, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, had experienced the non-sustainable impact of severe cost-cutting as a Government Minister in the early 1990s. He was well positioned to lead change with a deep understanding of the role and value of the State services and a relentless appetite for innovation and experimentation. He secured the support of the Prime Minister and Cabinet for reform and routinely spoke to senior public servants of the importance of their roles and the clear expectation that they deliver differently.19

Reform is difficult and expensive and more often than not fails. If you do not have a Reform Moment then do not attempt reform.

The importance of focus

There will always be more that requires reform than there will be capacity for change. So you must choose your focus wisely.

Do not attempt to change everything at once. During the reform process, there were significant attempts to generate grand unifying frameworks to describe, measure and change the performance of the entire New Zealand public management system. For the reform-minded this is a tempting pursuit, but with the power of hindsight it is apparent that these efforts contained the seed of their own failure. Complex systems defy comprehensive categorisation. Instead, the reforms progressively gained momentum by shifting the focus from comprehensive restructuring to improving the rules to enable change and then focusing on specific areas for implementation.

Do not try and change the things beyond the scope of this Reform Moment. For the Better Public Services Reforms, the clearest example of this was the interface between Ministers and Chief Executives hindering effective cross-agency collaboration. Changing the role of Ministers was not up for debate; the consistent desire for Chief Executives to concentrate on it as an issue reduced — rather than increased — the potential for significant change. Instead, focusing on changing the behaviour of public servants ultimately had some impact on Ministerial arrangements and behaviours.

Be results-focused. The Better Public Services Results have worked as a reform tool because of their degree of focus:

- Pick a few things — There are only 10 Results: they are not everything important government is doing in New Zealand and they are not even necessarily the 10 most important things that government is doing.

- That are important and on the path — The Ministerial decision to not engage in a lengthy analytical and consultation process for determining the 10 Results was key to capturing the Reform Moment in early 2012

- Get the right mandate — Labelling the Results as the Prime Minister’s Results sent a clear message to Ministers and civil servants that the Results mattered and that they needed to be prioritised against other work.

- Announce your intent — The radical step of publicly declaring the Result, the target and accountable Ministers and officials before having an agreed approach was a catalyst to cross-agency engagement in a system where most incentives ran in the other direction. Six-monthly reports have been publicly released on the progress on Results including the Cabinet paper, dashboard and underlying data.20

- Move at pace and adapt as you go — There was a clear imperative for agencies to develop an approach with urgency to deliver on Ministerial expectations and meet public reporting requirements. Having a target in place provided a catalyst for action; the targets and measures in turn could be strengthened with experience.

Intrinsic motivation and dynamism

One-off change is no longer enough. A complex and rapidly changing world requires dynamism. The strong focus on enabling, rather than prescriptive legislative change, recognises this imperative. However, the policy and design work for New Zealand’s reforms sought exclusively to depend on accountabilities, incentives and performance measurement to drive change. These approaches, derived from a New Public Management mindset, led to underplaying the importance of capturing hearts and minds in implementing reform.

Dynamism requires harnessing extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Successful reform required not just New Public Management and New Public Governance but also New Public Passion.21 The ten Results successfully aligned intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, but this was more by accident than design. The Results spoke to the key drivers of why many of the people working on the Results had become public servants in the first place. The passion of the leaders and teams for improving the lives of New Zealanders was essential in sustaining their efforts to overcome resistance to working differently.22

Making New Zealanders' dealings with government easy in a digital environment

Better Public Services Result 101 seeks to enable New Zealanders to complete their transactions with government easily in a digital environment. The measure of success is the proportion of New Zealanders’ most common transactions with government that are completed in a digital environment.

A Cabinet-approved Result 10 Blueprint sets out a shared vision for digital services that are digital by design, digital by default and digital by choice. The 10 actions in the Blueprint support customers to move to digital, redesign services and increase system capability.2

The target is to improve from 29.9% of services in June 2012 to 70% of services in December 2017. The shift achieved as at March 2016 is 52.2%.3 Ten services were measured, ranging from SmartGate departures and arrivals by NZ Customs Service, to filing and paying taxes through Inland Revenue and applying for financial assistance at the Ministry of Social Development.4

Ten Services Measured

1. SmartGate departures and arrivals

2. Renew adult passport

3. Apply for visa

4. Book Department of Conservation asset

5. Pay fines on time

6. Pay for Vehicle Licence

7. Apply for an IRD Number

8. File an Individual Tax Return

9. Pay Individual Tax

10. Apply for Financial Assistance

NOTES

- The Service Innovation Working Group, comprising the Chief Executives of eight agencies supporting the Government Chief Information Officer (who is also the Chief Executive of the Department of Internal Affairs), leads the delivery of Result 10.

- https://www.dia.govt.nz/Better-Public-Services

- Allen Schick, The Spirit of Reform: Managing the New Zealand State Sector in a Time of Change (New Zealand State Services Commission, 1996), https://www.ssc.govt.nz/spirit-of-reform; https://www.dia.govt.nz/Measuring-Results-Archive#July-Sept2012.

Figure 4. New Public Passion

CONCLUSION

The Better Public Services reforms have changed the rules, incentives and decision-rights of the New Zealand public management system to enable a step-change in cross-agency cooperation on complex and pressing issues. Despite this bureaucratic success, the proof of the value of this reform will only be in how it delivers improved results for New Zealanders. The Better Public Services Results will provide a clear and publicly transparent lead indicator of whether this change is taking place, with the current ongoing commitment to reporting six-monthly progress results, and on setting more challenging targets once the original objectives are reached.23 However, for the reform to be sustained, it will have to deliver more than ten results. The ongoing rate of change demands dynamism and the New Zealand public service will have to develop a passion for adaptation to continue to deliver on New Zealanders’ needs.

NOTES

- New Zealand Government, Better Public Services Advisory Group Report (November 2011).

- Judy Whitcombe, “Contributions and Challenges of “New Public Management”: New Zealand since 1984" (PDF,268KB), Policy Quarterly 4 (September 2006).

- On New Public Governance see: Stephen P. Osborne, The New Public Governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2010) and Jocelyne Bourgon, A New Synthesis of Public Administration: Serving in the 21st Century (Canada: McGill University Press, 2011).

- The Treasury, Government Management: Brief to the Incoming Government 1987 Volume I (1987).

- https://www.ssc.govt.nz/better-public-services.

- Better Public Services Paper 6: Amendments to the State Sector Act 1988 (PDF, 185KB) [SEC (12) 26] (4 May 2012).

- Better Public Services Paper 5: Amendments to the Public Finance Act 1989 (PDF, 117KB) [SEC (12) 25] (4 May 2012).

- Better Public Services Paper 7: Amendments to the Crown Entities Act 2004 (PDF,135KB)[SEC (12) 27] (4 May 2012).

- http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/betterpublicservices/crossagencyfunding.

- https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/integrated-data-infrastructure/.

- Core public Service agencies in New Zealand are led by a Chief Executive. The Chief Executive is appointed on a fixed term contract (typically 5 years) by the State Services Commissioner.

- See endnote 6; paragraphs 54 to 74.

- http://www.ssc.govt.nz/four-year-plans.

- http://www.ssc.govt.nz/performance-improvement-framework-reviews.

- Better Public Services Paper 2: Better System Leadership (PDF,96KB) [SEC (12) 22] (4 May 2012).

- https://www.ssc.govt.nz/bps-functional-leadershiphttp://www.mbie.govt.nz/.

- Allen Schick, The Spirit of Reform: Managing the New Zealand State Sector in a Time of Change (New Zealand State Services Commission, 1996).

- For example see: Bill English, Speech to IPANZ (New Zealand Government. 21 February 2013).

- A significant part of working on the New Zealand reforms was the opportunity to review and exchange information with reform efforts in a range of other jurisdictions. My general observation from these interactions and subsequent international advisory work is that the challenges are universal while the context in which those challenges occur demands solutions that are unique.

- See end note 5.

- For examples of agencies working together to deliver change, see http://www.ssc.govt.nz/better-public-services

- See end note 5.