Singapore’s Whole-of-Government Approach in Crisis Management

ETHOS Issue 16, Dec 2016

A STRUCTURE FOR INTER-AGENCY CRISIS MANAGEMENT

Literature on whole-of-government (WOG) issues rarely dwells on crisis management. Most scholarly work on WOG concentrates on improving public service delivery and addressing “wicked problems”,1 which is understandable given the extent and significance of these areas. Yet the coordination of multiple government agencies to deal with catastrophic events is critical: the lives and well-being of people in situations from large-scale disasters to terrorist attacks depend on it.

For independent Singapore, the genesis of crisis management can be traced to the Laju incident in 1974. The Laju was a ferry hijacked by four foreign terrorists in a bid to escape after setting off bombs at the Shell oil refinery.2 The terrorists’ grievances were not directed at Singapore but against the Netherlands — Shell being a Dutch company — for supporting Israel in the Middle Eastern conflict. Police prevented the terrorists from escaping but they took the Laju’s crewmen hostage. After eight days of standoff, the hijackers agreed to release the hostages in exchange for safe passage out of Singapore.

While the Laju hijack thus ended without bloodshed, the authorities at the time clearly lacked the proper capabilities to deal with the situation. An official book on the Singapore Police Force (SPF) acknowledged: “The Laju incident exposed the weakness of not having a sufficient reserve of trained officers who could be relied on to supplement regular officers during a security crisis”.3 Anti-hijacking forces and dedicated negotiators were not available as options to manage the crisis. Questions also arose over whether the director of internal security from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) or the director of intelligence from the Ministry of Defence (MINDEF) should lead the crisis management.4 The political leadership placed MINDEF’s director of intelligence in charge and the hijack was eventually resolved. But the incident highlighted the need for coordination among different agencies during such crises.

The Executive Group (EG) was subsequently set up “to handle hijacking and hostage taking”.5 The structure identified the leadership for handling such situations, appointing the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs as Chairman of the EG. Comprising senior officers from the security forces and various ministries (including communications and diplomatic agencies), the EG was the first inter-agency coordination platform across the Singapore Public Service.6

SINGAPORE’S CRISIS MANAGEMENT IN ACTION

1986: Hotel New World Collapse

When the Hotel New World collapsed in 1986 trapping survivors in the rubble, the Executive Group (EG) was fortuitously in the midst of a routine meeting and was able to coordinate the multi-agency rescue efforts immediately. The Singapore Police Force, Singapore Fire Service and the recently-created Singapore Civil Defence Force responded immediately. The Singapore Armed Forces, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Community Development, Public Works Department and other agencies were also mobilised to provide additional manpower, medical support, counselling for families of victims and engineering support. It was effectively a WOG operation. In all, 33 died but 17 lives were saved. The disaster vindicated earlier decisions to develop crisis response capabilities, as well as the effectiveness of the EG in coordinating inter-agency responses.1

1991: SQ117 Hijack

In 1991, four Pakistanis hijacked Singapore Airlines Flight SQ117 en route to Singapore. They held 114 passengers and 11 crew members hostage, in order to pressure the government of Pakistan to release some prisoners. The EG’s frequently-drilled plans went into action.2 A Negotiation Team comprising specially-trained police officers and psychologists established contact with the hijackers. When there was no breakthrough from the overnight talks, as the foreign authorities rejected the hijackers’ demands, the increasingly agitated hijackers threatened to kill the hostages at daybreak. EG ordered a storming of the plane. In less than 30 seconds, commandos killed all four terrorists, freeing all hostages. The successful resolution of the hijack vindicated earlier investments in specialised capabilities. It also demonstrated the value of regular cross-agency peacetime exercises in preparation for a crisis: they helped to blur boundary lines among agencies, forging various state capabilities into a single focused instrument for crisis resolution.

2003: SARS

When the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) virus reached Singapore in early 2003, the EG was activated to coordinate a government-wide response. The entire Public Service and citizen-volunteers were mobilised to conduct contact tracing and monitoring for 2,500 wholesale centre workers and 55,000 food centre workers across the country. This helped prevent the epidemic from spreading further through the vegetable supply chain. Although four Singaporeans succumbed to the virus, these coordinated efforts were effective in containing SARS: on 30 May, with no new cases recorded for 20 days, the World Health Organisation took Singapore off its “SARS list”, praising Singapore’s handling of the crisis as “exemplary”.3 The incident highlighted the need for the EG to be prepared for crises other than security threats: it soon set up cross-agency functional groups to cover areas such as transport, border control, education and housing.4

2013: Transboundary haze

In 2013, trans-boundary haze caused by slash-and-burn plantation farming in neighbouring Indonesia reached hazardous levels in Singapore. The health of the population, especially those with respiratory conditions, the elderly and young, was at risk, as well as low-income and vulnerable households less able to afford protective masks. The Homefront Crisis Executive Group activated its Crisis Management Group (Haze), which mobilised thousands of public officers from 23 different sectoral agencies along with citizen-volunteers. Together, they provided a comprehensive response to mitigate the socio-economic repercussions and to seek diplomatic solutions to the crisis. Well-rehearsed processes, strong executive capacity, the urgency of the situation and a collective sense of the national good meant that public officers looked beyond agency interests to tackle the haze. Eventually, a shift in wind direction at about the same time helped dissipate the haze and improved the situation.

NOTES

- James Low, “Overcoming Crises, Building Resilience,” in Heart of Public Service: Our Institutions (Singapore: Public Service Division, 2015): 132–45.

- Jagjit Singh, interview with author, March 19, 2015.

- Stephen Lambert, “Singapore: Waves of Transmission,” in SARS: How a Global Epidemic Was Stopped (Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2006): 101–08.

- Chua Mui Hoong, A Defining Moment: How Singapore Beat SARS (Singapore: Ministry of Information and the Arts, 2004).

WHOLE-OF-GOVERNMENT: ALIGNING MINDSET TO STRUCTURE

Ideas such as whole-of-government began appearing in the discourse of the Singapore Public Service around 2004. By then, “joined-up government” and “networked government” had been gaining traction in countries like Britain and New Zealand. There, the impetus arose from the fragmentation of public services stemming from large-scale new public management reforms. Singapore, having also corporatised some government functions to enhance efficiency, had encountered similar issues. How to apply WOG approaches to prepare for and deal with complex dilemmas, including crises, has since become a recurring theme in addresses by government leaders to public officers.

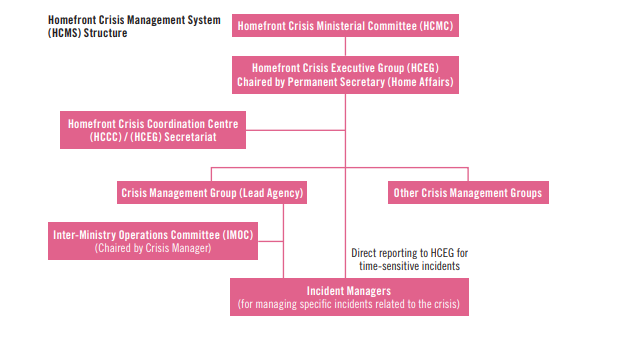

Crises are not restricted to security concerns, and could be highly complex, with wide-ranging implications on society and the economy. To render Singapore’s crisis management capabilities more comprehensive, the EG was reorganised in 2004 into the Homefront Crisis Executive Group (HCEG) (see Figure 1). HCEG comprised senior representatives from all ministries, reporting ultimately to the elected leadership for political direction. Under the HCEG’s oversight were taskforce-like Crisis Management Groups which could muster different clusters of relevant agencies to deal with different types of incidents.

Figure 1. Structure of the Homefront Crisis Management System.7

Source: National Security Coordination Secretariat, 1826 days: A diary of resolve: Securing Singapore since 9/11 (Singapore: National Security Coordination Secretariat, 2016).

While the HCEG may harness the whole Public Service to respond comprehensively to complex contingencies, the number of personnel to be mobilised now ranges in the thousands. At the same time, the continual drive to inculcate a whole-of-government mindset across the entire public service has helped to orient large numbers of public sector personal — both towards improved public services, but also towards concerted action in the event that a government-wide response is needed, including during times of crisis.

CULTIVATING WHOLE-OF-GOVERNMENT COORDINATION

Commit time, resources and practice to make it work

Organisational structures by themselves have nominal authority over agencies. It is the commitment of key leaders, as expressed in the adequate investment of time and resources, including frequent drills to anchor capabilities, that cements the credibility and effectiveness of the coordinating structure. Constant exercises smooth out the interface between agencies and personnel, allowing any unforeseen frictions or hindrances to be identified and rectified. Drills may pull agencies and officers away from routine work, and managers may cite important duties as justification to skip them, but the commitment and discipline to regular exercises is the “software” that allows the “hardware” of structural arrangements to be effective in inter-agency coordination.

Strong leadership with a shared ethos is a must

High-performing leadership across the bureaucracy allows the application of the best and most suitable minds towards managing crises when they arise. The high level of executive capacity aggregated in the EG and later the HCEG has certainly been instrumental in resolving Singapore’s various crises. Equally significant is the “shared language and culture” cultivated among the small cadre of public sector elite.1 The ethos among Administrative Officers in leadership positions up and down the hierarchy and across the Public Service helped ease communication and coordination among agencies during crisis management.

Whole-of-government culture needs to permeate the whole of government

A WOG-mindset among public officers at all levels is the software that lubricates the machinery of inter-agency crisis management, particularly when the numbers mobilised scales into the thousands for complex scenarios. In the Singapore Public Service, the constant reiteration of WOG thinking — along with communications about the larger national purpose they are serving — helps motivate officers to persist in the face of adversity, and to exercise initiative when needed at the working level.

NOTES

- Ow Foong Pheng, “View from the Centre: Working as One Government,” Ethos 9(2003): 15–17.

ADAPTABILITY OF LESSONS, WHAT’S NEXT FOR WOG?

Replicability and adaptability of lessons

Singapore is fortunate: its geography is relatively sheltered from natural disasters. The small jurisdiction and unitary system of government, unencumbered by multiple layers of bureaucracy seen elsewhere, aid governance. Furthermore, the country encountered crises that increased in intensity incrementally, allowing the state to scale up capabilities gradually to match. Singapore’s capacity to deal with crises has stemmed from deliberate, purposeful and comprehensive development, supported by an extended period of political continuity and economic growth.

Nevertheless, some of Singapore’s challenges are not dissimilar to those faced in other jurisdictions. Government agencies and civil servants around the world tend to be domain-specialised and instinctively turf-minded. Inter-agency collaboration can seem counter-intuitive to those in public sector in Singapore as elsewhere. In that regard, some of Singapore’s experiences in WOG could offer material for reflection.

From WOG to Whole-of-Society, Whole-of-Nation

The role the community could play in complex crises is becoming increasingly relevant. In Singapore, the public has shown itself ready to step forward in times of crisis. This was evident as early as the Hotel New World disaster, when citizen-volunteers with prior training joined regular personnel in the rescue efforts. Such civic-mindedness resurfaced during the 2003 SARS outbreak, and at the height of the 2013 haze episode, when individuals — without any prompting from the government — spontaneously stepped forward to help the needy people among the community.

The community could come to play yet more instrumental roles. After the September 11 attacks on the United States, local radicals calling themselves the Jemaah Islamiyah plotted terrorist attacks on targets in Singapore. Amidst risks of possible tension tearing at the fabric of the multi-ethnic society, leaders of different religious and ethnic communities rallied to denounce the hijacking of religion for terrorism and rallied together for ethnic harmony. Well respected Islamic teachers stepped forward to counsel and rehabilitate the detained radicals. These are roles the government cannot undertake with outcomes as effective as those played by the community.

National problems will become ever more complex: in some cases, the role government can play may be limited or constrained. While the government in Singapore has been effective in aligning the whole bureaucracy to function in whole-of-government fashion thus far, how can it seek to align the whole of society in the same way? If the Public Service is to help orient the whole of society, perhaps working as conveners, coordinators and interlocutors between government and the community in times of crisis, how can they be best prepared for this role? Some early work has started to consider these questions8 but more and deeper research on these issues should be carried out towards developing and strengthening whole-of-nation approaches to problem-solving and crisis management.

NOTES

- See: Tom Christensen and Per Laegreid, “Post-NPM reforms: whole-of-government approaches as a new trend,” in Research in Public Policy Analysis and Management, Volume 21: New steering concepts in public administration, eds. Sandra Groeneveld and Steven van de Walle (UK: Emerald, 2011): 11–24; John Wanna and Janine O’Flynn, Collaborative Governance: A New Era of Public Policy in Australia (Canberra: ANU E Press, 2008); John Halligan, “Public Management and Departments: Contemporary Themes – Future Agendas,” Australian Journal of Public Administration 64 (2005): 25–34; Tom Ling, “Delivering Joined-Up Government in the UK: Dimensions, Issues and Problems,” Public Administration 80 (2002): 615–42.

- See: S. R. Nathan, An Unexpected Journey: Path to the Presidency (Singapore: Editions Didler Millet, 2011); National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Centre, Interview with Tee Tua Ba, 2001, Accession No. 2323.

- Singapore Police Force, Policing Singapore in the 19th and 20th centuries (Singapore: Singapore Police Force, 2002).

- See: S. R. Nathan, An Unexpected Journey: Path to the Presidency (Singapore: Editions Didler Millet, 2011); Yoong Siew Wah, “A MediaCorp Caricature Presentation of the Laju Saga,” 28 April 2014, accessed 25 January 2016.

- National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Centre, Interview with Cheong Quee Wah, 1995, Accession No. 1611.

- Adapted from Oral History Interview with Cheong (see note 5) and National Security Coordination Centre, The Fight Against Terror: Singapore’s National Security Strategy (Singapore: National Security Coordination Centre, 2004).

- See: National Security Coordination Centre, The Fight Against Terror: Singapore’s National Security Strategy (Singapore: National Security Coordination Centre, 2004); National Security Coordination Secretariat, 1826 days: A diary of resolve: Securing Singapore since 9/11 (Singapore: National Security Coordination Secretariat, 2006).

- Charles Ng, “National Resilience: Developing a Whole-of-Society Response,” Ethos 10 (2011): 21–29.