From Scarcity to Generativity: New Approaches for Governing Resources

ETHOS Issue 16, Dec 2016

"… last year’s words belong to last year’s language And next year’s words await another voice."

—T. S. Eliot, “Little Gidding” in Four Quartets

One of my most abiding memories of studying Economics is how the first chapters of nearly all our textbooks were titled Scarcity: The Central Problem of Economics (or something similar). This made sense, since so much of the discipline is concerned with reconciling unlimited wants with limited resources, often through optimisation processes that “maximise” some variable (utility, profits, wages, lifetime income et al) within certain constraints and parameters. Such maximising approaches have extended to public policy, where efficient resource utilisation is often cited as a key priority of governments.

BEYOND SCARCITY

The fundamental assumption of scarcity works well for physical (and therefore finite) resources like oil or land, or even non-physical but nonetheless finite resources such as time. But it is less clear if scarcity characterises what we might call the “new resources” increasingly important in modern economies — data, knowledge, and connections underpinned by relationships — which can grow rather than deplete from being used, particularly given the rise of analytic capabilities and Internet-enabled network effects.

Consider some simple examples. Data begets more data once it has been interpreted and analysed: raw data on road usage, for instance, can generate new insights leading to new studies and models, perhaps even the collection of new data. One person’s knowledge — say, in a book or article like this one — can catalyse new ideas, interpretations and innovation. All successful thinkers and scholars stand on the shoulders of their predecessors and antecedents; even the most ground-breaking work draws on prior research. What Robert Putnam called the “social capital” underpinning relationships benefits from being tended, so that trust, reciprocity and predictability are created and nurtured, much like gardens generate new life from regular maintenance. Of course, data and knowledge need physical storage (although technological advancements challenge these limits) and relationships take attention and time to maintain and sustain. But one could call these limitations second-order scarcities: in and of themselves, the resources involved have no physical form, and no physical quantities to be “depleted” from use, so they are not “consumed” in the literal sense.

THE PARADIGM SO FAR

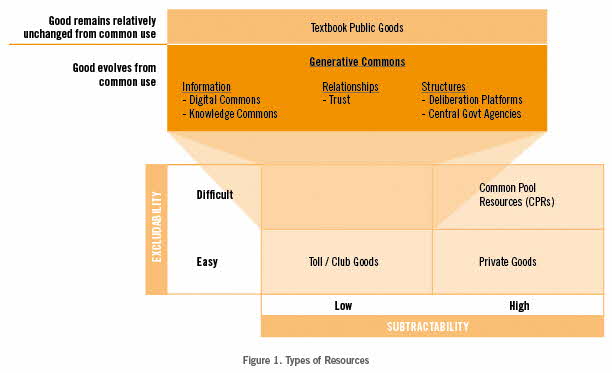

Traditional economics is only partially helpful in understanding the nature of such resources. Drawing on Elinor Ostrom’s Nobel Prize-winning studies of how common-pool resources are governed,1 and the prior work of Paul Samuelson,2 resources like data, knowledge and relationships would be seen as

- Non-rivalrous or non-subtractable: Person A’s consumption of data and knowledge, or experience of a relationship, does not prevent the simultaneous consumption/experience by Person B;

- Non-excludable: Person A could not stop Person B from consuming data or knowledge, or from being in a particular relationship.

The new resources increasingly important in modern economies — data, knowledge, and connections underpinned by relationships — can grow rather than deplete from being used.

Where the concepts of rivalry, subtractability and excludability falter is their assumption that goods do not change in the process of being utilised or experienced. Public goods, like street-lighting, lighthouses and defence, which Samuelson cites, or the rivers, fisheries and forests that formed Ostrom’s key case studies, all stay relatively unchanged because of consumption, even if they can transform due to external or systemic factors. In contrast, data, knowledge and relationships are fundamentally altered when they are utilised, because this very utilisation results in more of each resource being created. This unique category of resources is reflected in Figure 1.

GENERATIVE RESOURCES

As outlined in Figure 1, I describe such resources as “generative”. Given the inadequacy of existing descriptions, we need what T. S. Eliot might have called a fundamentally different language for, and way of thinking about, what generative resources are and how they work. Some useful ideas come from French sociologist Marcel Mauss’ work on what he terms a “gift economy”, where things have intangible value even if their tangible worth is unclear, and are exchanged reciprocally rather than as instrumental, capitalist commodities.3 However, while Mauss’ process of exchanging gifts is indeed generative, he does not account for the generativity of the gifts themselves (the additional usage created for each resource).

On this latter issue, the conceptual heavy-lifting is only just beginning. For now, five themes seem to be particularly critical in defining this new vocabulary:

- Generative resources are not static but constantly evolving. This might seem obvious, until we remember that for the better part of history, our notion of resources has focused on substances like wood, iron and oil, which stayed by and large the same during a productive process. Physical states sometimes changed, but at its core, each resource was relatively immutable. In contrast, generative resources are dynamic and iterative: data feeds on itself, networks generate cycles that can be virtuous or vicious, and social capital can undergo both quantitative and qualitative transformations as a result of relationship-building within a community.

- Generative resources exhibit “input-output polymorphism”. It is difficult to tell whether things like data, knowledge and social capital constitute input into, or output from, productive processes. I suspect that the input-output dichotomy, while useful for a world where goods and services were produced in linear, discrete processes, is much less relevant when resources and raw “materials” are less tangible. There are inevitable feedback loops between input and output, each feeding into and fed by the other. Old lines between production and consumption, or producers and consumers, will grow less salient over time. We will all increasingly become “prosumers” in our interactions with generative resources.

- Generative resources suffer, not from overuse (which prompted Garrett Hardin to coin the famous term “tragedy of the commons”4), but underuse. Websites bereft of traffic; physical and online networks atrophying under the weight of sluggish usage; prediction algorithms with insufficient training data; neglected communities on the sidelines of cities — the lost potential and capacity in each of these are certainly tragic. But the tragedy lies in insufficient rather than excessive exploitation — sometimes by choice, in the case of relationships, and sometimes because we lack the computational and/or cognitive power to analyse new data or knowledge. Again, underuse is related to second-order scarcities: time, attention and capacity are limited, even if the resources on which they act are generative. In fact, on the issue of knowledge, Ostrom and her collaborators5 distinguish between ideas themselves (which display generativity), and the artifacts and facilities that contain them (which are subject to second-order scarcities). We could apply similar reasoning to relationships, differentiating between the generative social capital of the relationship itself, and the scarce repositories or structures within they play out. The sobering reality is that such second-order scarcities will not disappear easily, although they can be mitigated with technological improvement and innovation.

- As a result of their evolving nature, generative resources do not have clear boundaries, but fuzzy and dynamic edges. We usually rely on well-defined boundaries when governing a resource: knowing the boundaries of oil deposits, for instance, is key in deciding the validity of ownership claims. But where do things like data, networks and relationships start or end? If clear boundaries allow for clear principles of governance, then fuzzy and dynamic boundaries may also require governance by fuzzy and adaptive logic — broad norms underpinning the use of a resource, rather than mere physical concepts like quantity. Ostrom’s work on fisheries and forests offers clues on what such norms might look like — fishermen collectively choose to adhere to norms of throwing young fish (below a certain length) back into the water, while trees with trunks below a certain diameter are deliberately left untouched by loggers. These norms can only be imperfectly enforced — hence their fuzziness — and may need to evolve with time. But Ostrom suggests that self-organising, self-monitoring communities can actually achieve reasonably high rates of adherence within these conditions — in some cases, better than outcomes achieved by either top-down state interventions or market-based solutions. This could apply equally to data and knowledge (collective norms in universities on plagiarism, for instance) or norms governing the behaviour of communities, both on- and offline.

- The intangible and evolving nature of such resources mean that there are few clear “equilibrium” points in the way they can be used or managed. Much as equilibria help to simplify analysis in what economists call “comparative statics”, the real world does not usually exhibit stable or immutable equilibria. Instead, the ways in which data, knowledge and relationships are used, as well as sustained, are likely to be much more emergent and unpredictable ex ante. The optimisation approaches so ubiquitous in much of Economics may need to start giving way to design-based, behavioural approaches that emphasise iterative and experimental learning by discovery.

The existence of data, knowledge and relationships does not signify that we are somehow moving into a world of utopian abundance. There will still be more wants than can be met with current productive capacity.

WHAT'S NEXT — POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The existence of data, knowledge and relationships does not signify that we are somehow moving into a world of utopian abundance. Many important resources will continue to be scarce — oil, minerals, water, time. There will still be more wants than can be met with current productive capacity. Wants that are satisfied will still be subject to inequity of outcomes and/or poor distribution systems. Generative resources may not be exhaustible in the orthodox economic sense, but they can still be degraded (e.g. falsified data or relationships that corrode without trust): the property of generativity just means that the mechanics of their generation and exhaustion are different from those of more classical resources.

But Singapore and the world can certainly afford to move away from a pure scarcity mindset — particularly since the digital economy has significantly accelerated the trend of generativity. The claims of commentators like Jeremy Rifkin, heralding the rise of “The Zero Marginal Cost Society”,6are probably overstated — second-order scarcities may continue to mean that not all that is “free” is also usable, and new problems may arise from data overload and informational or relational promiscuity. But opportunities are undeniably created when digitalisation reduces the cost of duplication or replication of data, knowledge and connections until it reaches close to zero.

To help us harness these opportunities, the new language of generativity will have to lead to new thinking, particularly in how we make and implement policy. For instance:

- The evolving nature of generative resources, as well as their input-output polymorphism, will require changes in how we measure economic value — not just through static traditional measures like GDP, but through new measures that capture the catalytic effects caused by resource use. Such new measures are very much works-in-progress, but it is telling that new and more variegated indicators of human welfare, like the Legatum Institute’s Prosperity Index, include a sub-index on generative resources like Social Capital.

- Tragedies of the generative commons, arising from under- rather than over-use, will need new and creative approaches to tax and regulatory policy, in which some forms of exploitation should be encouraged rather than limited. The numerous examples of such existing constraints — big companies protecting the data they gather, relationships being confined to narrow networks (e.g. traditional old boys’ clubs), or knowledge restricted behind paywalls — might actually be described as a third order of scarcity: a “generated scarcity” that is contrived in order to maintain particular individual or organisational interests. The great sociologist of science, Robert Merton,7 refers to the Gospel of Matthew (25:29) when he describes such generated scarcities as examples of the ‘Matthew Effect’, where “… whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them”.

- Greater public participation in public policy — more deliberation by citizens on the decisions that affect their lives, and more policy that is truly “of, by and for” the people — is one key way to guard against the risk of underuse. In many ways, generative resources are like muscles, and public participation is a good way to ensure their constant use, stretching and suppleness. Indeed, such engagement can itself be generative, leading to the creation of new knowledge and learning, civic awareness and social capital among mutually engaged citizens.

- Fuzzy and dynamic edges will have important ramifications for how we define intellectual property, which will need to be seen as much more dynamic and kaleidoscopic. Assigning precise ownership over extended periods will grow increasingly complicated — and will need to be calibrated in order to avoid third-order scarcity induced by the Matthew Effect, and to maintain the generativity of resources.

- Lack of clear equilibrium points calls for a more systems-oriented approach that considers not just individual agents and nodes, but their interactions within larger ecologies. This means analysing the interactions among pieces of knowledge, exploring the creative potential of networks, and tapping into the collaborative capacity in generative relationships. Some of this has already been proposed by scholars of complexity science and complex adaptive systems, who explore how non-linear, interdependent systems require fundamentally different approaches from the stable, predictable systems popularised by the European Enlightenment. But the links can be deepened and broadened through further research.

NEW DIRECTIONS

It is probably too soon to predict what the first chapters of Economics textbooks will look like in a few years, but hopefully the new language of generativity begins to creep into them, to supplement (even if it does not entirely supplant) the deep assumption of scarcity. This new language may not lead to new answers immediately, but will still be useful if it raises new questions that eventually mark out paths towards new words and new voices.

NOTES

- Elinor Ostrom, Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems (The Nobel Foundation, 2009).

- Paul A. Samuelson, “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 36(1954): 387–89.

- Marcel Mauss, The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies (London: Cohen and West, 1966). Translation by I. Cunnison.

- Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162(1968): 1243–8.

- Charlotte Hess and Elinor Ostrom, eds., Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011).

- Jeremy Rifkin, The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism (Palgrave MacMillan, 2014).

- R. Merton, “The Matthew Effect in Science,” Science 159(1968): 56–63.