Enabling Organisational Transformation: Possibilities and Practice

ETHOS Issue 13, May 2014

What is Transformation and What is Not?

The context within which the public sector operates has changed. Public agencies today seek the capacity to transform their organisations and navigate the dynamic environments in which they must serve. More and more of the issues they face have become trans-boundary, multidimensional, interconnected and prone to surprises. Public agencies increasingly have to juggle traditional roles as public service provider, regulator and law enforcer as well as new, relational ones as arbiter, facilitator and convener — all within the constraints of allocated budgets and manpower.

Yet organisational transformations are challenging. Research suggests that only one third of organisations that try to transform do so successfully.1 Organisational transformation is not about tweaking parts of the system. Instead, it involves a whole-system shift in the way an organisation thinks, operates and relates with others. It is not just about raising standards, working faster or tightening controls, but redefining an organisation’s desired outcomes. It requires a shift from the problem-solving mode to a focus on a vision of the desired future the organisation wants to create. The process is complex, because transformation is an emergent phenomenon, comprising many moving parts and interdependent agents, and requiring individuals to change mind-sets and behaviours.

Organisational Transformation: Different Models, Different Approaches

There are many models for understanding organisational transformation.

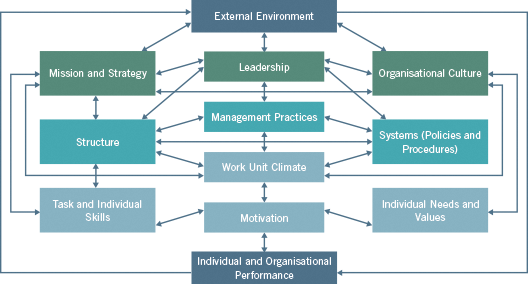

The Burke-Litwin model of organisational change and performance (Figure 1)1 suggests that an organisation’s mission and strategy, organisational culture and leadership are transformational factors that can create organisation-wide impact. The organisation’s structure, systems and management practices are regarded as transactional factors that may not impact the whole organisation when changed. Changes in transformational and transactional factors impact individuals’ values, needs, motivation, job roles, skills and therefore performance that in turn affect organisation performance.

Figure 1. Burke-Litwin model (1992). Reproduced with permission.

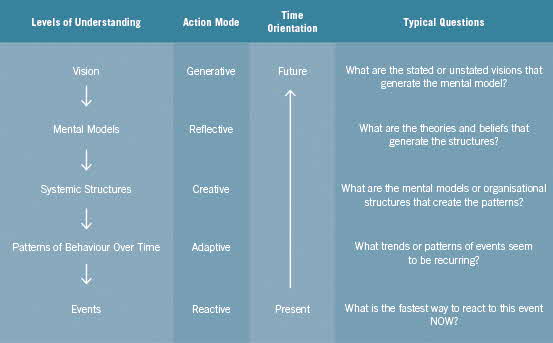

Figure 2. Daniel H. Kim’s Levels of Perspective Framework.

Reproduced with permission.

While high-leverage actions can happen at any level depending on the context, actions at the higher levels have greater impact on future outcomes. Analysing an issue from multiple levels can give us a fuller understanding of the system at work. It also prevents us from reacting with quick-fixes only at the events level.

There is also a body of work that views all transformation as linguistic. For instance, author Peter Block argues that transformation “hinges on changing the structure of how we engage each other”.3 Our conversations and the way we relate reflect our mental models that in turn determine our actions. One way to facilitate change is therefore to reframe mental models by changing the nature of conversations within an organisation. We start with a small group, which is the unit of transformation. Large-scale transformation happens when enough small groups shift in unison towards a common goal. Every gathering is an opportunity to reinforce and deepen individuals’ accountability and commitment towards the desired collective outcome.

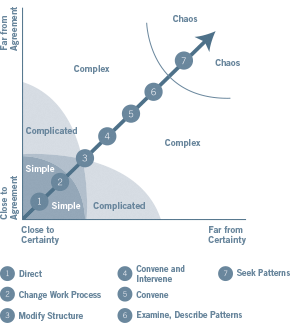

Ralph Stacey, one of the early thinkers to bridge complexity science with organisation theory, mapped organisational challenges into a continuum: simple, complicated, complex and chaos, based on their proximity from agreement and certainty. Plexus Institute, a US-based non-profit organisation that applies complexity science concepts to problems in organisations and communities, has been using Stacey’s continuum to address a range of issues in health care. It added to the model by defining change strategies for different parts of Stacey’s continuum (Figure 3). Its work suggests that, in practice, all four zones are present all the time in most change situations. For example, checklists can be useful reminders, but they are insufficient to address the complexity of challenges individuals face as new scenarios emerge.

Figure 3. Amalgamation of Ralph Stacey’s Agreement-Uncertainty Diagram and Plexus’ Change Strategies for Different parts of the continuum Diagram.4 Reproduced with permission.

- W. Warner Burke and George H. Litwin, “A Causal Model of Organisational Performance and Change,” Journal of Management 8 (1992): 523–546.

- Daniel H. Kim, Organizing for Learning: Strategies for Knowledge Creation and Enduring Change (Massachusetts: Pegasus Communications, 2001).

- Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2008): 25.

- Adapted from diagram of “Change Strategies for Different parts of the Continuum” from the Plexus Institute (http://www.plexusinstitute.org) and “Stacey’s Agreement–Uncertainty” in Brenda Zimmerman, Curt Lindberg, and Paul Plsek, Edgeware: Lessons from Complexity Science for Health Care Leaders (Irving, TX: VHA, Inc., 2008), as cited in Lisa Kimball, “A Powerful Distinction: How the Simple-Complicated-Complex Continuum Contributes to OD Practice,” OD Practitioner 45 (2013): 43–48.

Fixing the System or Creating a New One?

Organisational change begins with the organisation’s mission and vision of the future, and the nature of the change that is called for. It may be that deeper and more sustainable change comes not from trying to fix the existing system, but by creating a new one. This may call for a fundamental re-think of the organisation’s purpose and desired outcomes.

Becoming more aware of the different levels of perspective on which we operate — and the inter-relationships of change variables involved — helps us better determine the most effective levers for change. It will also be easier to connect the pieces if we perceive the bigger picture of the system. It allows organisations to attend to the immediate while working in concert, at multiple levels in multiple action modes, towards larger shared goals.

If the nature of most organisational change is complex and our goal is also to grow the capacity to anticipate and adapt to change over time, then there is merit in broadening conversations. This means widening the circle of involvement by engaging more people: across levels and roles, and even outside the organisation. It means taking time to help people see the larger scheme of things and their collective contribution, by reframing mental models, building a clearer and shared view of the future through new experiences of coming together. If transformation is emergent, then there is a need to structure processes for experimenting, learning and course-correcting — through conversations at different levels that enable all stakeholders to seek meaningful patterns and understand collectively.

Leadership sponsorship and modelling at all levels are crucial for change. Leaders are in a unique position to shape the context in which people and systems come together to achieve outcomes. They identify the issues and larger purpose, and engage people in new conversations. They build the collective capacity of groups and their whole organisation to create new realities by managing relationships across, and by empowering through, the design of organisational systems. The exercise of leadership, in providing coherence, connection and commitment to the whole, confers meaning and sustains excellence.

Organisational Transformation in Action: Two Public Agencies in Singapore

Singapore Customs (SC) and the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS), both agencies under the purview of Singapore’s Ministry of Finance, navigated significant changes in their mission, vision and organisation. They were able to do so successfully while sustaining performance and retaining committed public officers.2

To tighten border control following September 11, border enforcement roles under the former Customs & Excise Department, a government department under the Ministry of Finance, were transferred to the new Immigration & Checkpoints Authority in 2003. The remaining trade documentation and revenue enforcement roles of the Customs & Excise Department and the trade facilitation function of International Enterprise Singapore, a statutory board under the Ministry of Trade and Industry, were merged to form Singapore Customs, which would become the single agency to look after all the functions along the trade chain. In the decade that followed, SC’s role rapidly expanded and its staff strength almost doubled to take on a diversity of trade facilitation and security functions in a period of tremendous volatility in global trade.

When IRAS became a statutory board in 1992, 50% of tax returns were not assessed, employee morale was low and the attrition rate at 11% was four times the Civil Service’s average. Over two decades, IRAS went through three major transformations, shifting from a focus on tax administration efficiency to partnership with taxpayers in nation building and economic development.

What can we learn from their organisational transformation journeys? The transformations in SC and IRAS began with a fundamental rethink of their respective missions. Both transformations were emergent and spanned years. Both comprised concurrent interventions at multiple levels of perspective. They attended to immediate concerns at the event level such as streamlining operations, reducing backlogs, improving service quality and raising productivity, while simultaneously envisioning their organisations’ future, which subsequently gave shape and direction to their strategies. New mental models of their roles — as custodians of trade, and as partners of taxpayers in nation building and economic development — emerged in the process, leading to new solutions and partnerships, and generating new patterns of behaviours and capabilities.

First, SC and IRAS management used their corporate mission and vision to align systems and galvanise people. They helped their employees understand the larger purpose of their organisations, and how their individual efforts collectively contributed to the whole. They emphasised “whole-of-organisation” priorities over divisional interests, and promoted “think trade” and “think IRAS” mind-sets. To facilitate shifts in behaviours, they contextualised high-level aspirations with specific examples and achievable goals that their employees could act on. Practice was supported by process design. Both agencies:

- framed deliberations and decisions in the context of organisation-wide goals, for example, in developing corporate strategy, designing organisational structures and processes, and deliberating HR issues such as succession planning and posting.

- designed work to accentuate inter-dependence and encourage collaboration through cross-divisional project teams, interbranch enforcement exercises, interdivisional manpower sharing during tax-filing peaks, and by celebrating organisational (rather than divisional) success.

- instituted mandatory job postings to broaden and deepen employees’ understanding of organisational challenges, and to enable them to forge networks across the organisation.

- created multiple channels to share information and knowledge — across the organisation, with other public agency partners and with stakeholders, such as the trading community, tax professionals, companies and overseas counterparts — to expand staff’s perspective of their operating environment and mission.

Second, both SC and IRAS used conversation as a capacity enabler. Conversation was used to shape corporate culture. Conversations at every level, from boardrooms and town halls to team interactions, helped to surface and correct misalignments in thinking and practice, such as reframing positions from “my and my division’s interests” to “our and Singapore’s interests”. This refocused energies on the need to steward the collective enterprise, and to work as a team. Conversation was also used to strengthen the agencies’ capacity to anticipate and adapt to change — to take the pulse on the ground, connect diverse perspectives, sense-make and correct course. It also improved employees’ awareness of agency-wide challenges, primed employees for priority shifts, and promoted ownership of organisational issues. SC and IRAS institutionalised conversations as an organisational practice and both agencies:

- designed conversation into their change and work plan processes. Leaders catalysed rather than dictated change. They led conversations to give direction, model change and enlist participation. Middle management refined and translated ideas to action with their teams, and ground feedback was used to inform planning and decision-making.

- invited employees to volunteer on taskforces that worked on inputs from dialogues. Staff could influence changes that affected them, and those who volunteered were more committed to act.

- equipped their employees with necessary skills. All SC supervisors went on coaching programmes. Senior and middle management in IRAS were trained in Learning Organisation (LO) tools and concepts. These tools expanded their capacity to hold difficult conversations and be more open as a group.

- recognised that relationship and trust create safe environments for conversations. A variety of staff well-being and team-building opportunities helped officers across each organisation to bond, and reassured employees that the organisation cares for them.

Third, leaders contributed through connecting and capacity building. SC and IRAS leaders encouraged dialogue and participation, connected people to their shared purpose and to each other, and nurtured community. A positive experience of leadership engendered trust and drew followers. The following stood out in both organisations:

- Cohesiveness of the leadership team. Top leaders, who were Administrative Service officers posted from other agencies in the Public Service, introduced new perspectives and networks. They were supported by a strong core management team, most of whom rose from within the ranks, who provided stability. Regular job rotations deepened the core team’s understanding of organisational issues, broadened their social networks and helped them build shared perspectives. This enabled them to better anticipate the impact of their actions on the rest of the organisation, and to engage fruitfully with other partners and stakeholders.

- Extensive involvement of leaders in organisational life. SC and IRAS leaders invested time in engaging employees. The Director-General of SC had tea with different Customs officers at least once a week, and the IRAS Quality Service Chairman met with officers who received outstanding compliments monthly. Senior management leaders led cross-functional committees, shared at induction programmes, mentored young officers, evaluated staff suggestions and participated in employee wellbeing activities. This gave them many opportunities to gather feedback, understand the ground and influence thinking.

- Both organisations designed structures and systems to enable the practice of leadership at all levels. Frequent and open communication reduced the power–distance gap and empowered employees to act. Ground and frontline staff were entrusted with leadership roles and responsibilities. For example, non-graduate officers made presentations to senior management, led teams and oversaw operations. A checkpoints team lead shared with pride how his presentation on his job responsibilities resulted in the creation of a promotional grade for his scheme. Change agents were at work at all levels.

Transformation is About Our Choice of Future

SC and IRAS were relentless in pursuing their agency visions, but their management also invested heavily in the health of their organisations and cultivated a sense of shared identity. They addressed immediate needs, while at the same time promoting alignment of goals, and building up the capacity of their people and systems to achieve better results over time.

At their respective levels, leaders reframed organisational challenges as opportunities for growth, used conversation as a tool to influence thinking and facilitate team learning, and empowered people by anticipating needs, giving them information, roles and choices, and by investing in relationships, building trust and learning. Consequently, employees were engaged, better able to anticipate change as priorities shifted, better able to understand the context for change, and more ready to adapt as shifts emerged.

SC and IRAS demonstrate the powerful possibilities of organisational transformation over time. If our objective for public sector transformation is to build institutions that can anticipate, adapt and prosper over the years, how do the ways in which we frame transformation and design our organisations serve the future we want to create?

NOTES

- McKinsey Company, “What Successful Transformations Share: McKinsey Global Survey Results,” McKinsey Quarterly 2010.

- For more information, please see: Lena Leong, “IRAS: From Regulator to Service Provider to Partner of Taxpayers in Nation Building and Economic Development”, Civil Service College (2013), https://www.cscollege.gov.sg/knowledge/pages/iras-from-regulator-to-service-provider-to-partner-of-taxpayers-in-nation-building--economic-development.aspx, and Lena Leong, “Singapore Customs: The Journey from Good to Great”, Civil Service College (2014), https://www.cscollege.gov.sg/knowledge/pages/singapore-customs-the-journey-from-good-to-great.aspx