Opinion: The Future of Futures

ETHOS Issue 07, Jan 2010

FUTURES TODAY

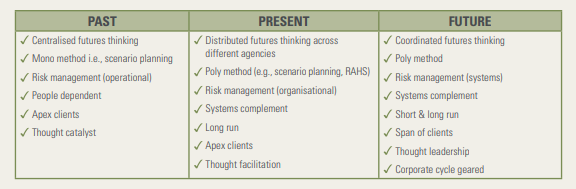

Futures thinking is not new to the Singapore Government. Scenario planning was first introduced in the 1990s. Since then, the discipline and practice of futures thinking has become more sophisticated and populated. A much wider range of futures methodologies have been considered and applied. The public sector's understanding of the challenges and complexities of futures analysis has grown with experience; so have the resources committed to futures thinking.

Two decades ago, futures thinking in the Public Service was the function of one central unit employing primarily one methodology—scenario planning. Futures thinking at that time was talent-centred: a group of officers were systematically trained and grouped together in the Scenario Planning Office to carry out scenario planning from a national perspective. The clients of futures thinking were the top was to help catalyse the framing of new perspectives.

Today, there are several futures units within government. Each focuses on its own band of issues and serves the strategic needs of its respective organisational management.

Our repertoire of futures thinking tools has also grown. In the recent past, we can be said to have moved from risk management at the single-issue level to organisational level considerations. The framing of risk takes in a wide band of associated issues and policies of concern to the client agency. We have also complemented the traditional talent-centred model with systems such as risk assessment and horizon scanning (RAHS). More is expected of futures units today. They are expected to also be thought facilitators. They deploy their skills and systems to help management think through issues thrown up by futures thinking in some detail and with texture and nuance.

What the Delphi Oracle can Tell Us about Futures

The desire to know the future has been a preoccupation of humankind since time immemorial, along with its attendant culture and processes. Those who sought the wisdom of the Greek oracle at Delphi, for instance, had to deliberate carefully on what to ask and how to phrase the question they would pose to the sacred oracle.1 Such queries had to be accompanied by substantial payment and any pronouncements were regarded as divine, so this was a serious business. The "clients" who sought wisdom at Delphi were trying to manage the uncertainty which they felt hazarded their futures. Their consultations were made with a view to action.

The most famous example of a Delphic consultation was that which led to the Battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. The Athenians were fearful of invasion by the Persians and they consulted at Delphi. The three-part forecast they received was hardly comforting. First, they were told there would be a "wooden wall" which would remain unconquered. Second, the Athenians were told to flee their city. Third, it was pronounced that many young men would die near the island of Salamis.

The Athenian leaders were dejected with this prophecy, which seemed to conclusively portend their defeat. However, rather than despair, they engaged in debate on what to make of this news. Finally, one of their statesmen, Themistocles, made the case that the "wooden wall" referred not to the city walls but to the massed wooden ships of the Athenian navy. He pointed out that the prophecy of "many young men will die" did not necessarily mean many Greek men. He took the view that in the face of a larger opposing army, it was only sensible for the people to flee the city: the Athenians would fight the Persians at sea in the narrow straits off the Salamis and cut their lines of communication. This is what they proceeded to do and the Persians were defeated in the ensuing sea battle.

This legendary episode suggests that futures thinking is never a single event but a process, and one which involves a serious commitment from the seekers of foresight in reviewing their strategic priorities even before embarking on such an attempt. Furthermore, the burden is on the "client", in this case the Athenians, to do most of the work and not on the "consultant" futurist (the oracle of Delphi). Three stages which define the futures process can be identified.

Stage 1: Strategic Inquiry

An organisation that intends to employ futures thinking should be clear about its strategic priorities and concerns. The Athenians had to consider the threat to them, their own strengths and weaknesses and their objectives. This calculation allowed them to arrive at a decision to temporarily sacrifice their city for the greater strategic result of decisively defeating the Persians. Management must have some normative sense of direction for the organisation. Through a process of strategic inquiry, an organisation's futures team should be given clear questions to consider. Muddy or ambiguous scoping will almost certainly lead to vague or irrelevant futures products.

Stage 2: Strategic Debate

Organisations sometimes expect their futures teams to deliver "turnkey" solutions or recommendations. This is tantamount to futurists telling management what to do, which is not their appropriate role. Their processes can lead to rethinking, strategic reframing or fresh insights, but not prescriptions for action. Instead, the task of interpreting and analysing futures products is the job of management. The Athenians struggled to interpret Delphi's pronouncements, but ultimately, it was by reframing their analysis through debate and lateral thinking that they arrived at a more promising strategic perspective than the bleak outlook they had originally confronted.

Stage 3: Strategic Decision

By combining the Delphic pronouncement and Themistocles' strategic thinking, the Athenians reframed their perspective from one of despair to one of initiative. But the Athenians also followed through this strategic process with decisive action. Decision encompasses action, but management needs to also take responsibility for the consequences of their actions. The longevity of the Delphi oracle was not because her prophecies always led to positive results, but because her clients accepted that they were owners of the eventual outcomes.

∼ Devadas Krishnadas

Notes

- The modern parallel might be the use of a focal question to scope scenario thinking.

THE FUTURE OF FUTURES

There are several ways in which futures thinking in government might usefully evolve from this point forward.

First, we should complete the move toward risk management at the systems level. This approach will permit us to accept tradeoffs in higher risk in order to take advantage of greater opportunities. Systems level risk management makes us aware of complexities and brings to light hidden dimensions left undiscovered by lower levels of analysis. A systems level risk management model operates best at the Whole-of-Government (WOG) level.

Second, we should recognise the importance of communicating the rationale for direction in strategy to an increasingly well-educated and informed executive layer in our organisations. Consequently, we should reframe our consideration of who the clients of futures products are— and consider including a wider span of management levels. The increasing pace of world events and technological change legitimises lowering the range limit on what constitutes relevant futures thinking.

Third, futures units should be prepared to consider shorter term outlooks of perhaps three to five years when the degree of uncertainty warrants it, where once their domain was more naturally geared towards the 30- to 50-year range.

Finally, there are benefits in coordinating the activity of futures units that have proliferated across different segments of government. Futures units in the public sector today differ widely in terms of their competency, capability and capacity, as well as in their degree of organisational maturity. While the different units started out from different policy mandates, there is growing recognition that every major issue has dimensions which interface with others. For instance, social issues should take into consideration economics and industrial organisational futures, as these will have impact on wages and composition of the labour force which, in turn, will potentially modify assumptions about the distribution of income and shape of the social needs picture. This can allow for a customised packaging of skills, methods and systems to deal with specific questions or problems, as well as reap inter-agency or WOG synergies.

THE POWER OF MULTIPLE FUTURES

Coordinating and optimising futures thinking resources across the different futures units in the public sector have several implications.

3C Mapping

A mapping of the distribution of the carrying competencies, capabilities and capacities of futures units within government might be needed. Competency refers to skill sets, capability to systems and capacity to size and budgets. This will permit an informed approach to coordinating collaboration in order to reach scale for complex futures challenges. A working principle should be adopted, which requires futures units to be mutually supportive. Such an arrangement would also obviate the need for each unit to acquire similar systems or grow capacity to ensure a wide range of in-house capabilities.

Public Sector Futurists

Over the past decade, new futures units have been set up and legacy ones modified. Futures units in the Singapore Public Service now straddle a wide range of policy domains:

- The Strategic Policy Office (formerly the Scenario Planning Office) develops strategic planning and policy capabilities at the national level and across the whole of government.

- The Risk Assessment and Horizon Scanning (RAHS) programme within the National Security Coordination

- The Ministry of Trade and Industry Futures Group monitors the economic, trade and industrial landscape.

- A Futures Group within the Future Systems Directorate in the Ministry of Defence studies the future operating environment of the armed forces, and identifies defence-related challenges, opportunities and threats.

- A Futures Team at the Ministry of Community, Youth and Sports studies the application of futures thinking to the social policy domain on a project basis.

Notes

- The modern parallel might be the use of a focal question to scope scenario thinking.

The establishment of the Centre for Strategic Futures is a step in this direction and further consolidates the whole-of-government spirit necessary to tackle complex futures.

Tractability

Futures units should offer thought leadership by proactively and independently providing new ideas and perspectives to senior management. Futures products should also ideally be delivered within the context of corporate strategy and budget cycles. This is to ensure that they are channelled to the attention of senior management at key decision-making junctions, when major commitments are about to be made.

Discrete Channels

Not all forms of futures thinking are the same. We have matured from a single methodology to multiple methodologies, yet this could lead to a misplaced assumption that the various futures thinking processes and products are interchangeable. A distinction should be made as to which processes and systems, and which combinations thereof, are best suited for particular tasks.

A distinction should also be made of the varying purposes of futures thinking. There may be three discrete strategic purposes:

Normative Strategies

Futures thinking attempts that posit long-range possible futures, or visioning, may be best suited to generating normative strategies. Such strategies are intended to realise desirable futures or avoid undesirable ones. They tend to be complex and slow-moving in execution, but have long-lasting effects and involve sticky, usually major, commitments, such as structural changes to the education system or economy.

Opportunistic Strategies

Strategies which can be rapidly executed and can involve reversible commitments may benefit most from horizon scanning— shorter range focused studies that throw up new variables and new relationships between known variables. An example could be a revision in investment strategies for sovereign wealth funds to take advantage of growth sectors, new resource discoveries or changing consumer patterns.

Contingency Strategies

Efforts to detect Black Swans and Wild Cards1 can usefully lead to the generation of contingency strategies. These are deferred or conditional strategies aimed at coping with Black Swans or Wild Cards by negating or moderating the causal factors of Black Swans and by creating strategic buffers to absorb the shock of Wild Cards.

CHOICES

Singapore has a maturing community of futures thinkers in government and considerable experience with the processes of futures thinking. We also continue to push forward with experimentation and new learning. A relatively early investment in futures thinking capability means the Singapore Public Service now has the luxury of refining its choices as to how to organise, process, and use futures thinking. It is up to us to make these decisions thoughtfully, even if only the future will tell if we have made them wisely.

NOTES

- Based on ideas popularised by Nassim Taleb, Black Swans can be defined as high impact but low probability events that are very difficult to detect in advance because of preconceptions. Wild Cards are potential events which may be tangential to strategic priorities but whose occurrence would have disruptive consequences, such as pandemics and game-changing technological breakthroughs.