Opinion: Mainstreaming the Praxis of Foresight: The UK Example

ETHOS Issue 07, Jan 2010

Foresight is not prediction; it is a natural human faculty used in everyday decision-making. It involves understanding how past and current events can inform decisions taken in the present, to reach desired outcomes in the future.

At the organisational level, foresight is more than simply a long-term work plan. It involves the gathering and synthesising of a variety of individual assessments to make strategic decisions that create the best possible outcomes for all stakeholders, across multiple domains and time frames.

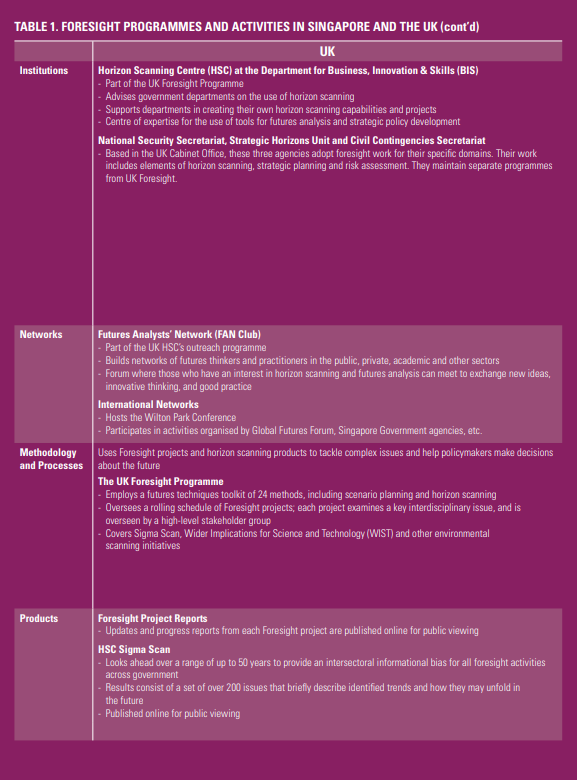

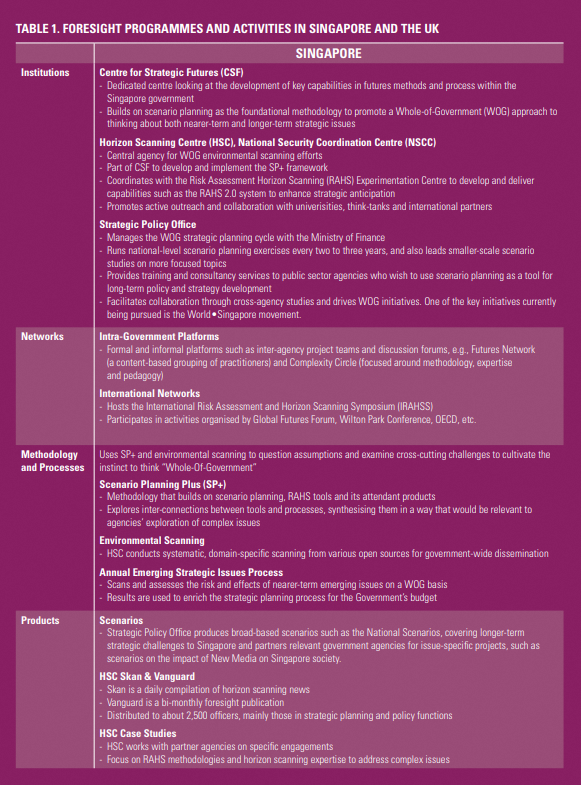

Foresight has to be practised; to this end, governments and private organisations have embarked on widespread foresight programmes and activities varying in breadth, depth and sophistication (see Table 1).

The UK Foresight Programme, with its stated role "to help government think systematically about the future", is an example of an established approach to the praxis of foresight in the public sector.1 Observation of the UK Programme reveals four useful insights:

1. BUILD A ROBUST ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

Foresight activities have to be aligned towards clear strategic anticipatory goals. This orientation can be towards downstream activities or specific to a narrow time frame—this was the case with the UK Civil Contingencies Secretariat's (CCS) risk register, which assesses the most significant emergencies the country will face over the next five years.2 The CCS uses the document as a basis for monitoring partner agencies' risk mitigation efforts, and as part of its efforts in public education and outreach.

Foresight work can also be oriented upstream towards more open-ended parameters with a longer time frame, as evinced by the UK's Sigma Scan, which collates future issues and trends for the next 20 to 80 years as identified by various horizon scanning sources.3 The UK Horizon Scanning Centre uses the material in case studies, workshops and programmes to work towards better strategic planning and policy-making.

Regardless of the strategic anticipatory orientation chosen, the methodologies employed need to be robust and credible. The UK emphasises an evidence-based approach that anchors foresight work on quality research and sources, clear and quantifiable indicators, and empirical data. The UK Government, by engaging a lead expert group for each project and allowing the public online access to their material, helps to ensure that their foresight work holds up to the analytical scrutiny of a wider community of experts and non-experts alike.

2. NETWORKS ARE IMPORTANT

The UK Government's emphasis on wider engagement stands in contrast to the common notion that foresight is best suited to mavericks and contrarians, who can spot strategic issues ahead of others. On the contrary, it is crucial for foresight work to harness inputs and opinions as broadly as possible. In this sense, picking the right mix of persons to contribute to a project is just as important as their area and level of expertise. This involves maintaining good working relationships through networks that are built laterally across agencies, and also with individuals and organisations outside of government. These networks serve as intellectual checks and balances, and allow for assumptions to be challenged and strategies to be stress-tested.

For example, each UK Foresight project leverages a variety of networks: other than its lead expert group, the project also answers to a high-level stakeholder group, and consults with think-tanks, universities and private sector stakeholders when drawing up inputs and shaping findings.

Furthermore, the UK Horizon Scanning Centre also functions as the government's hub for horizon scanning and foresight expertise, providing information and capability building services to other agencies. Besides conferences, seminars and international collaboration, the Centre also runs the Futures Analysts' Network, which is a forum for people with an interest in futures analysis, from both the public and private sectors, to exchange ideas and good practices.

3. ENSURE POLICY RELEVANCE

Robust and credible foresight work has to be relevant to policy and invested with sufficient management buy-in to ensure that findings and recommendations are given due consideration and followed through. Foresight projects in the UK are carefully chosen to address cross-departmental policy issues with action-oriented outcomes. Each project has to be supported by a lead government department and its Minister must agree to chair a high-level stakeholder group of senior decision-makers and budget-holders from relevant departments, research councils and other organisations. The government's Chief Scientific Adviser sits on each of these stakeholder groups as well.

A foresight programme should be seen as part of a larger endeavour to institutionalise and make mainstream habits of mind that challenge prevailing assumptions.

Once buy-in from higher management and stakeholders is secured, attention has to be given to communicating of foresight products in effective ways. Heavily researched analysis and complex scenarios need to be presented in a detailed yet incisive manner for decision makers to understand and subsequently take action. To this end, the UK foresight projects are crafted to be well signposted, monitored and regularly updated within the stakeholders’ communities as part of the implementation process.

4. MAKE FORESIGHT MAINSTREAM

The praxis of foresight in an organisation extends beyond the nuts and bolts of its research activities and even its integration with strategic planning processes. Instead, it should be seen as part of a larger endeavour to institutionalise and make mainstream habits of mind that challenge prevailing assumptions, recognise cognitive biases and examine issues with a wide horizontal impact across multiple domains.

The UK’s networked approach is illustrative of the principle that the responsibility for foresight should not fall solely on a dedicated group of strategic thinkers, practitioners and horizon scanners; nor should it be assumed that foresight work would gain traction without any institutional backing or centre of expertise.

Cultivating an appreciation of strategic futures methodologies in departments has built a stronger culture of foresight in the UK government. This is seen in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s (FCO) use of complexity science in their analyses, and in other agencies building their own research and horizon scanning capabilities.

As observed from the UK’s experience, the explicit goal of a foresight programme is for public of f icials to think systematically about the future. Given the need for public policymaking to become ever more adroit, adaptive and astute, such an endeavour is nothing short of a transformative process to institutionalise the praxis of foresight at all levels of government.

NOTES