Opinion: Looking for Trouble

ETHOS Issue 07, Jan 2010

INTRODUCTION

Every government has a responsibility to identify potential crises in order to avoid them or ameliorate their effects. The sooner a government can identify a problem, the easier the job of avoiding or containing it because fewer resources will be needed, and more time will be available to mobilise those resources.

Therefore, government agencies may attempt to pick up the weak signals that indicate that a crisis may be brewing. They may develop systematic methods and technologies for scanning more and more data, and for connecting the dots. They may strive for higher levels of accuracy, seeking to root out errors that might lead to mistakes of omission (failing to spot weak signals) or commission (crying wolf). A metaphor would be the use of space-based telescopes to spot asteroids that might be heading towards our planet, in the hope that with enough time we might find a way to deflect the orbit of such asteroids away from us.

While I think that all of these steps are valuable, I have some concerns with each of them. I worry that the way an agency pursues each of these steps can increase its vulnerability, if it is not careful. The steps I have described above emphasise the gathering of information over analysis. They emphasise technology and procedures over expertise. They are best suited for recurring crises, rather than a first-of-a-kind crisis.

Returning to the metaphor of a killer asteroid, the threat of asteroids is not new. It is a recurrent crisis. Our planet has been shaken by asteroids in the past. They are cited as a likely reason for the extinction of dinosaurs, and for a massive explosion in Siberia in 1908. Asteroid-hunting is a poor metaphor for the challenge of detecting first-of-a-kind crises such as the airborne suicide attacks of 9/11, Pearl Harbor, the collapse of Enron, and the current global economic meltdown. First-of-a-kind crises correspond to the black swans that Taleb has discussed.1 Thus, in hindsight, the weak signals were there in plain view for 9/11, for Pearl Harbor, for the collapse of Enron, for the US economic crisis in the fall of 2007.

Using computational models to spot weak signals is like driving a car by looking in the rearview mirror.

Most people missed the weak signals because, as Karl Weick has pointed out in his book Sensemaking in Organizations,2 we understand the significance of the weak signals only in hindsight. Weak signals do not announce themselves, particularly for first-of-a-kind crises. In hindsight, we can see the signs of the US housing bubble several years ago. We can shake our heads at the granting of home loans to people with limited resources. But there have been bubbles before this. What made this bubble so devastating was that it was associated with lax regulations, insufficient risk analyses by the Wall Street investment banks, infusion of capital from thriving Asian economies, a perversion of the loan insurance practices for mortgage-backed securities so that they accelerated risk rather than dampened it, loss of transparency for financial instruments, and so forth. Each of these signals was commented on at the time, but it was the combination of these factors that led to the crisis.

In The March of Folly, Barbara Tuchman described a number of world events that seem inevitable in hindsight, but were invisible to the decision makers at the time.3 Gathering more data would not help decision makers who cannot understand what the data mean, and computational models work best by extrapolating from previous events and historical trends. Computational models assume continuity with the past and are even less sensitive to first-of-a-kind events than people are. Using these models is like driving a car by looking in one's rear-view mirror. The sophisticated computational models used by Wall Street were no match for the realities of the fall of 2007.

Not only are weak signals hard to spot, but when keen observers do pick them up they usually have trouble convincing others to pay attention. In each of the cases I listed above—Pearl Harbor, 9/11, the economic meltdown—a few people identified the weak signals and tried to warn others. In each case, the warning was ignored. It is not just that weak signals are hard to detect and hard to understand. They are hard to communicate because they are so unusual and unlikely that they do not fit the mindset of the decision makers.

TOO MUCH INFORMATION GATHERING CAN OBSCURE ANALYSIS

Government agencies may attempt to pick up the weak signals that indicate that a crisis may be brewing, but the signals only make sense in context, in relation to the rest of the situation. Thus, each of the forces that led to the financial crisis that hit the US in the fall of 2007 were fairly visible (excepting the deceptions practised by Bear Stearns and others), but there was little government enthusiasm for reining in the low-inflation growth that seemed to be generating such prosperity, until it was too late.

Reducing mistakes is not the same thing as fostering insights.

Agencies may develop systematic methods and technologies for scanning more and more data, but a point is soon reached where more data results in more ambiguity. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was fairly obvious, in hindsight, but the plethora of signals made it easier to anticipate a Japanese attack on Russia, or a bold move to the south to ensure a supply of oil. Besides, decision makers are very good at explaining away data that they do not like. Analysts may be encouraged to "connect the dots", but the dots are only clear in hindsight; the skill of analysts is in judging what counts as a dot in the first place.4

Agencies that feel themselves to be under pressure often become risk-averse. They may adopt a zero-deficit mindset, adding all kinds of practices to increase accuracy and reduce mistakes, but reducing mistakes is not the same thing as fostering insights. If we try to reduce mistakes by having people document all of their assumptions and areas of uncertainty, we may instil a passive attitude that gets in the way of actively searching for potential crises. We see some evidence of this in the intelligence community, where new analysts are assured that if they just follow proper tradecraft (for example, document assumptions and areas of uncertainty), no one will blame them if they make a mistake. If we try to reduce mistakes by directing people to consider more hypotheses, we may interfere with their ability to use their intuitions. If we persuade people to look for historical trends, and force them to use statistics to justify their judgments, we risk missing the first-of-a-kind crises. Thus, during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, the advocates of tradecraft assured President Kennedy that the USSR would not try to put ballistic missiles in Cuba because their entire history showed an avoidance of risk. Afterwards, when it was clear that this assessment was incorrect, the explanation was that Khrushchev had acted irrationally, not that their tradecraft had failed.

HOW TO LOOK FOR TROUBLE

Therefore, in addition to the usual steps, we can take the following actions: Encourage people to look into the anomalies they notice rather than passively keeping an open mind. Maintain a variety of perspectives and backgrounds. Help people to see situations from different perspectives. Rotate in people who have fresh eyes and haven't been part of the prevailing wisdom. These suggestions are reasonably obvious, along with the advice to increase openness and adaptation.

However, organisations incur a cost when they become less predictable and run into coordination difficulties. Predictability is essential for organisational coordination. Perhaps what is needed is a split-level organisational style in which the leader is responsible for consistent performance and mature oversight, but can draw on subordinates who are speculative, reacting or even over-reacting to potential trends and threats. If the leader shows this type of variability, the organisation may suffer. Better to depend on subordinates who are free to speculate. This advice comes with a catch—subordinates who do their job of freely speculating will often be wrong, which will likely reduce their credibility. It is hard to regain credibility. Therefore, when leaders find themselves dismissing comments from the speculators, it may be time to rotate in some new warning officers.

Perhaps what is needed are leaders responsible for performance and oversight, with subordinates who are speculative.

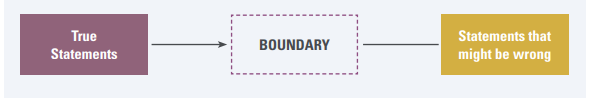

One way to see if an organisation is harvesting the worries of people trying to pick up weak signals is to look at the products they generate. Imagine a continuum from statements that are very likely to be true, to statements that might well be wrong. And imagine a boundary line, separating the region of true statements from the region of possible errors.

The harder challenge is getting higher ups in the organisation to take these early indications seriously.

In a risk-averse environment, analysts will be very reluctant to offer opinions that might be wrong. They will avoid the boundary line, moving as far to the accurate pole as possible. That is fine—except that their statements and observations will carry very little information value. More desirable is a situation where people go in the opposite direction. They migrate to the boundary line, trying to make the most extreme observations that they believe they can defend. These are the insights, the risky predictions, the disruptive opinions that can be so valuable.

There do not seem to be any special skills for spotting weak signals, other than a contrarian attitude. However, by encouraging speculation rather than conformity, curiosity rather than avoidance of mistakes, disagreement over harmony, we may be able to increase success in noticing the early indications of threats.

The harder challenge is getting higher ups in the organisation to take these early indications seriously. Efforts here will involve breaking them out of their fixations. They will have to give up their old mindsets before they can seriously entertain new ways of viewing events and threats.

NOTES

- Taleb, Nassim N., The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (USA: Random House, 2007).

- Weick, Karl E., Sensemaking in Organizations (USA: Sage Publications, Inc., 1995).

- Tuchman, Barbara W., The March of Folly (USA: Ballantine Books, 1985). 04. Klein, G., Streetlights and shadows: Searching for the keys to adaptive decision making (USA: MIT Press, 2009).