Encouraging Car Lite Travel through Gamification: The Kids Smart Travel Challenge

ETHOS Digital Issue 05, Nov 2019

Over-reliance on private car transport is one of the leading contributors to many lifestyle and environmental problems, including traffic congestion, increased greenhouse gas emissions, and reduced physical activity.

In the United Kingdom, it is estimated that 1 in 4 cars on the road during the morning peak are dropping off children at school, despite them living an average of only 2.5 km1 away. In Singapore, a commonly heard complaint is localised traffic congestion around school start and end times due to drop-offs and pick-ups by private car.

Schools have tried to manage this congestion by staggering assembly and dismissal timings. This solution merely treats the problem in a superficial way, without addressing the root cause of the issue, which is the unnecessary use of private cars.

Encouraging people to switch to car-lite modes of transport requires multi-faceted and innovative solutions. Issues to be addressed include habits and behaviours, aspirations, attitudes and the relative ease of getting from home to school through different travel modes, such as walking or public transport.

An Experiment with Gamification

In 2018, the Economics Unit of the Land Transport Authority (LTA) and the Social and Economics team of the Civil Service College embarked on a study using gamification techniques to encourage car-lite2 travel among primary school students. Inspired by the “Monkey Money” project in Davis, California,3 the first-of-its-kind pilot study in Singapore built on well-established behavioural insights, particularly people’s desire to perform well and actively contribute to team performance in social settings.

The Kids Smart Travel Challenge (KSTC) aimed to answer two questions:

a) Can gamification shift students’ choice of transport mode to school from car to car-lite in a sustained manner?

b) Can gamification change students’ and parents’ attitudes towards car-lite travel modes?

Partnering with Bukit Panjang Primary School

We looked for primary schools with a larger proportion of students living near the school premises. We made a list of schools for which local congestion was a significant problem, based on feedback received by LTA. Of the identified schools, Bukit Panjang Primary School (BPPS) agreed to participate in the KSTC pilot, which lasted from 15 January until 4 April 2018.

BPPS allowed us to trial the game with their Primary 5 (P5) and Primary 6 (P6) students, which were our preferred target age group. We assessed that their parents might be more comfortable with allowing them to take car-lite modes to school on their own, since they were relatively more mature. This would also be a good opportunity to prepare them for the transition to secondary school.

Designing the Game

The KSTC had two core design elements—extrinsic incentives and intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic incentives were to bring students on board to kick start the switch from car to car-lite modes. Intrinsic motivations were needed to sustain the behaviour by improving attitudes towards public transport and internalising the benefits of going car-lite.

Behavioural insights were used to reinforce the extrinsic and intrinsic motivations, by designing the following aspects into the game:

i. Social competition: the tendency to compete in achieving social recognition during games and competition, and the desire to contribute to team performance;

ii. Saliency: how people are more likely to respond to stimuli that are novel, simple and accessible, e.g., periodical reminders; and

iii. Commitment devices: a tendency to follow through goals once people write down their goals, which also serve as an effective reminder.

.jpg)

Playing the Game

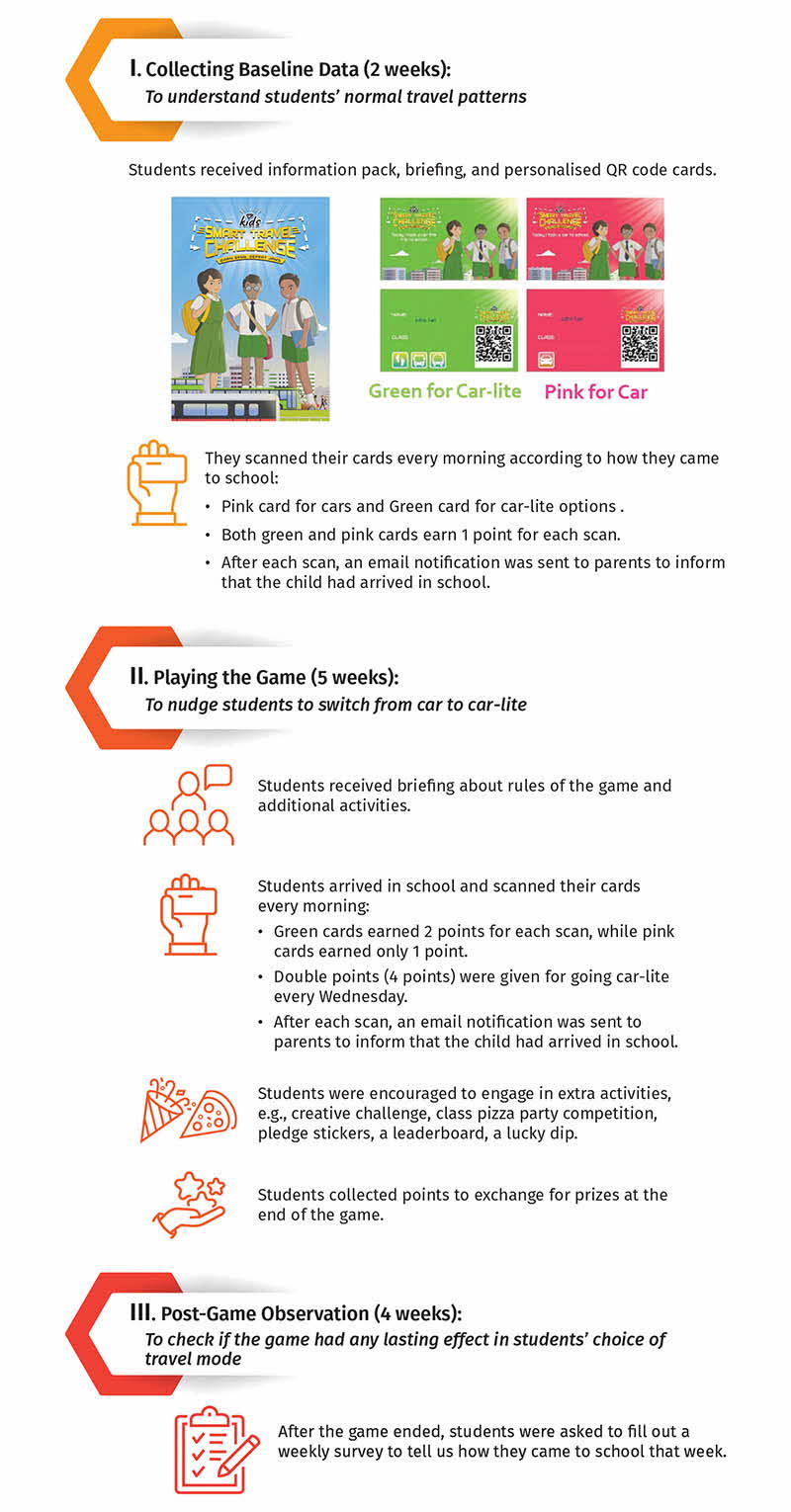

KSTC was carried out in three stages

Students get their cards scanned upon arrival in school

Students exchange their collected points for prizes

What We Found Out from the Game

1. The game was effective in shifting students towards taking more car-lite trips.

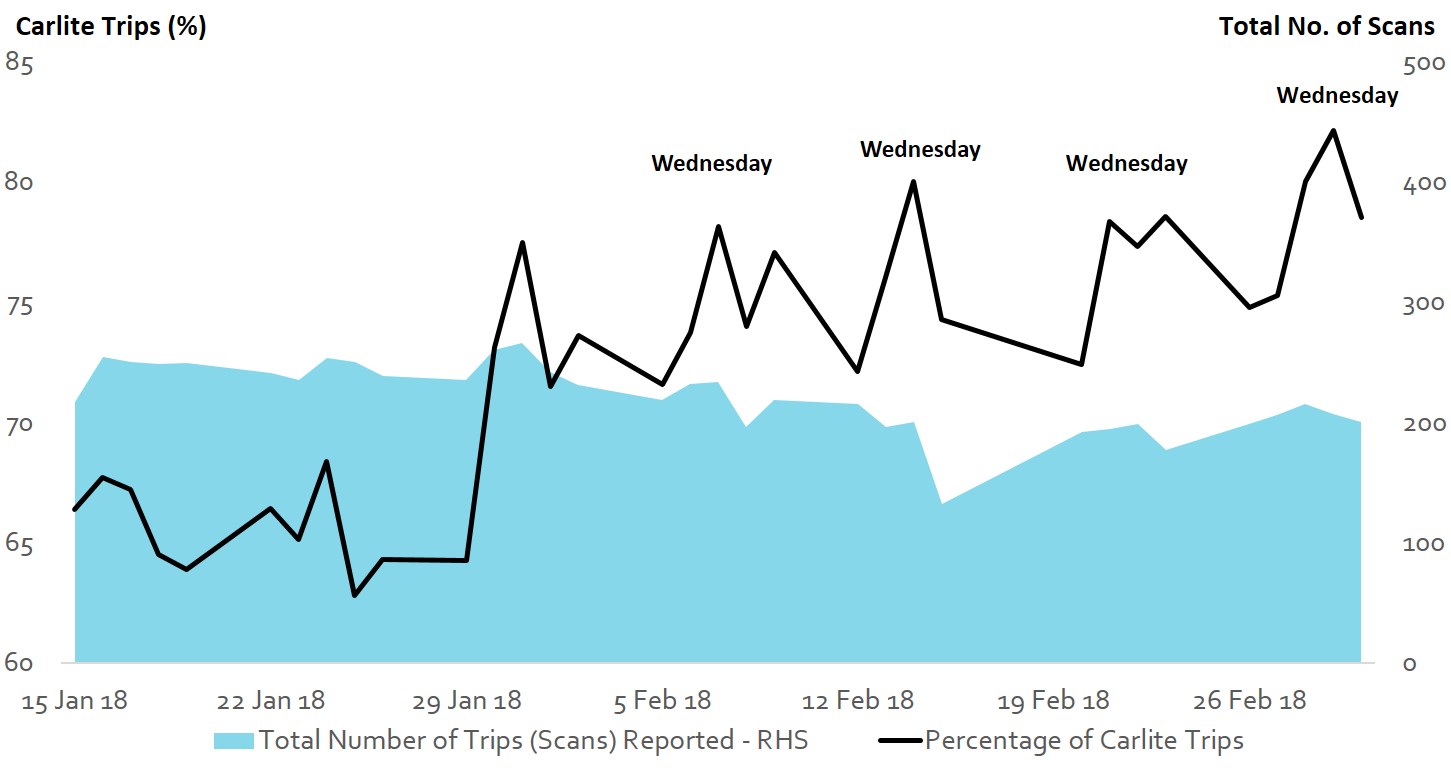

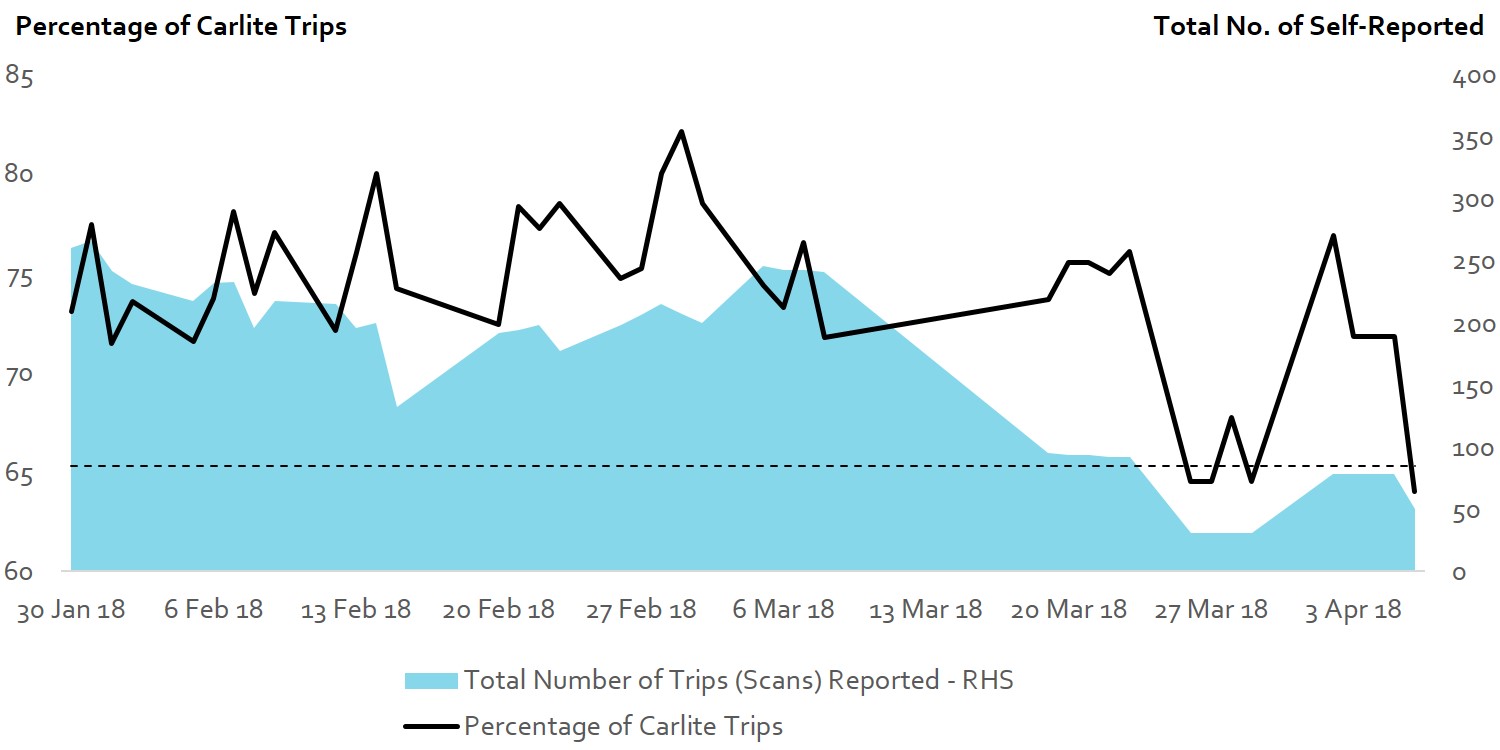

During the 5 weeks of the game phase, the proportion of car-lite trips increased from 66% to 76%, with clear peaks observed on every “double-point” Wednesday (see Figure 1). After the game ended, we observed students’ travel patterns for another 4 weeks: the proportion of car-lite trips dropped compared to the game period, but stayed higher than the baseline average of 66% (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Proportion of Car-Lite Trips Taken during Baseline (2 Weeks) and the Game (5 weeks)

Figure 2. Proportion of Car-Lite Trips Taken Post-Game (4 weeks)*

*During the week of 27 March, Primary 5 students were away on camp so the data captured during that week was inaccurate.

2. Parents’ confidence in their child’s ability to take public transport alone was a key factor in students switching from car to car-lite during the game.

We administered surveys to parents and students before and after the game. Comparing students who did not make the switch from car to car-lite to those who did during the game phase, we found that parents of the latter group had noticeably higher confidence in their children’s ability to take public transport alone. Answers for other related questions such as “child’s aspiration for car”, “child’s confidence in taking public transport alone”, and “parents’ perceived accessibility of public transport” were similar between both groups

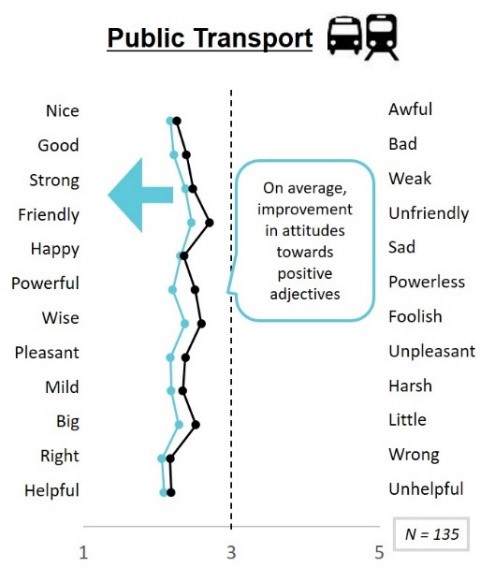

3. Attitudes of parents became more positive towards public transport after the game.

Based on semantic differentials4 in the survey administered to the parents, we also found that the game improved parents’ attitudes towards public transport (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Survey Results from Parents on Their Attitudes towards Public Transport Before (Black Line) and After (Blue Line) the Game

What We Learnt

1. Gamification can be effective in changing behaviours. But sustaining the effect over time may require repeated interventions and/or a longer intervention period. Interestingly, the KSTC’s effects went beyond the children who participated: it also positively influenced the attitudes of parents towards public transport. This points to the potential of reaching out to parents on desired social behaviours by engaging their children. However, the effect seems to diminish when the game is stopped. To maintain the effect for long-term, it would be useful to have either a longer intervention or repeated interventions and reminders from time to time to reinforce the desired behaviour.

Effects went beyond the children who participated: it also positively influenced the attitudes of parents towards public transport.

2. Careful use of extrinsic incentives was essential in bringing students on-board and sustaining their interest in the game. Studies have shown that relying too much on extrinsic incentives can crowd-out intrinsic motivations, causing behaviour to revert to former patterns after incentives are stopped. For this trial, we tried initially to keep the focus on intrinsic motivations and de-emphasise extrinsic incentives: for example, by not revealing the party prizes. We soon realised that the students were very much motivated extrinsically, especially when the behavioural change requires substantial effort. This reiterates the importance of striking a careful balance between extrinsic incentives and intrinsic motivations, and points to the need for a compelling game narrative that activates intrinsic motivations in future iterations of the game.

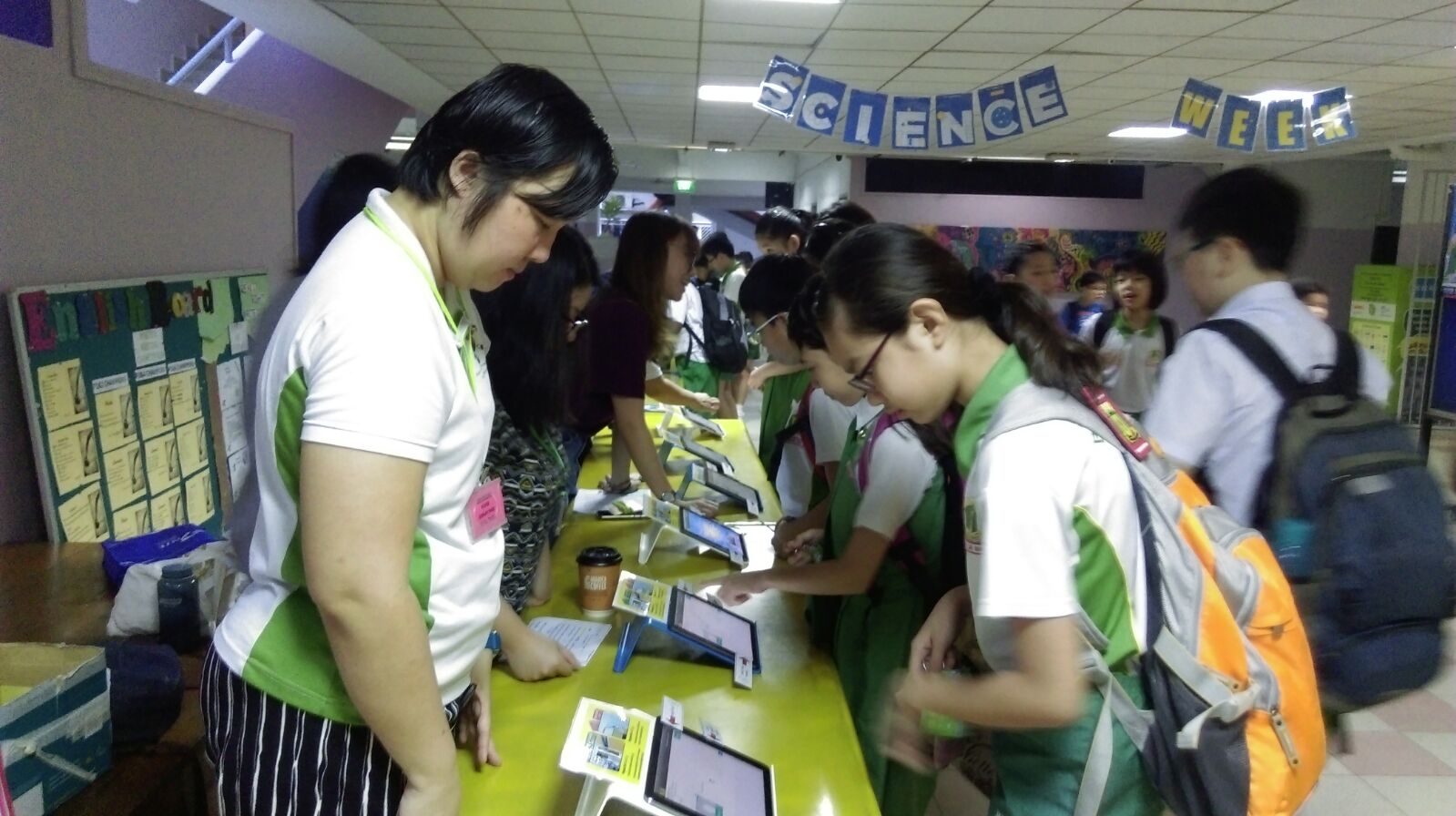

Parent volunteer manning the scanning kiosk

3. In this trial that involved primary school children, a blend of face-to-face and digital elements were important to the success of the game. Scanning and iPads made it fun, while seeing a physical scanning kiosk and familiar faces every day was crucial in building rapport with students to gain valuable feedback and to minimise cheating. This points to a potential trade-off that game designers need to consider when replacing face-to-face elements with technology for efficiency and saving on manpower.

A blend of face-to-face and digital elements were important to the success of the game.

4. Hanging out at the “scanning area” also provided students with opportunities to bond with their friends and classmates before school, including friends whom they had not met in some time. This social interaction was a positive spinoff that the team had not expected at the game’s conceptualisation stage. It demonstrated the potential of games to encourage more social interactions and mixing in an organic manner, in addition to bringing about the intended behavioural change.

Games encourage more social interactions, in addition to bringing about the intended behavioural change.

5. Multiple partners and stakeholders saw to the fruition of the pilot. Each partner and stakeholder played different roles—the school leadership’s go-ahead for the pilot opened the doors, while parents and parent volunteers were essential to the sustainability of the seven-week pilot. The parent volunteer group in particular helped extensively during the scanning period, which meant that we could minimise teachers’ involvement. The students who were playing the game gave us practical ideas and ongoing feedback on how to address the challenges we faced, most notably, how to generate excitement and sustain interest during the full duration of the game. The pizza party for instance was an idea borne out of such feedback, when we experienced declining participation rates midway through the game. They also challenged our assumptions around what would be considered “attractive prizes” to students, by suggesting alternative prizes. It is common wisdom that partners and stakeholders play an important role in the success of any pilot, but understanding how each can contribute and in what capacity, was key to the success of KSTC.

The students who were playing the game gave us practical ideas and ongoing feedback on how to address the challenges we faced.

Parent volunteers

Token of appreciation presentation to the principal of Bukit Panjang Primary School

Next Steps?

The success of the KSTC pilot has given LTA new impetus to introduce gamification concepts to more schools. Potential refinements include complementing the car-lite message with hands-on transport challenges (e.g., student-sourced barrier free walking routes), to strengthen the educational content of the game. LTA also plans to work with other government bodies, such as the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources and its agencies, to strengthen game design in appealing to a wider range of sustainable behaviours beyond car-lite travel, such as resource conservation. Concurrently, a customised app for the game is being developed to minimise the manpower required and to improve features such as the saliency of the game, i.e., by providing immediate feedback on how many points a student has earned when he/she scans in. More importantly, the KSTC pilot has revealed broader learning points on the value of gamification and what its limitations are for the benefit of future game designers in the public sector.

NOTES

- Sustrans, “Walking or Wheeling the School Run”, May 14, 2019, accessed October 15, 2019, https://www.sustrans.org.uk/our-blog/get-active/2019/everyday-walking-and-cycling/walking-or-wheeling-the-school-run/.

- Car-lite in this pilot refers to walking, biking, taking public transportation, school bus, and walking after being dropped-off at the nearest LRT/MRT stations.

- Calvin Thigpen, “Barcodes, Virtual Money, and Golden Wheels: The Influence of Davis, CA Schools’ Bicycling Encouragement Programs”, Case Studies on Transport Policy 7 (June 2019):414–422, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2019.02.005.

- Semantic differentials is a methodology where respondents are showed several pair of words that represent opposite ends of a scale. Respondents then have to check the box on the scale which best describes their feelings towards a certain topic (in this case it was public transport in Singapore). This methodology minimises framing effects, gives a more diverse perspective on attitudes by using different adjectives, and can be completed quite quickly.