AI in Government: Trust Before Transformation

ETHOS Digital Issue 13, Oct 2025

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping our world at a pace and scale never-before-seen in human history. What was previously computationally impossible or expensive can become reality in mere seconds on personal devices. AI has the potential to empower millions, unlocking humanity's capacity to think, act, and dream in unprecedented ways.

Yet trust is required for this potential to materialise for government – trust that is elusive. A 2023 KPMG study found that three out of five (61%) people are wary about trusting AI systems and three quarters (73%) are concerned about its potential risks. Unfortunately, they also have the least confidence in the government's capacity to develop, utilise, and govern AI in the public's best interest, in comparison to other entities such as universities.

So how should government leaders engender trusted AI, and trust in AI?

The Ethical AI-Powered Government

AI-Empowered Service Delivery: User-Centred Control Of Data

In the realm of service delivery, governments worldwide are transitioning from a multichannel model, characterised by fragmented databases and service touchpoints, to an integrated, omnichannel approach. In this new model, information flows seamlessly between databases, eliminating the need for users to repeat themselves. Instead of completing forms, users can engage with a chatbot, which can extract relevant information through voice chats, images, and document scans, and channel the data to the appropriate agencies directly. Aggregated data on users’ preferences and profile will enable AI to proactively recommend government services tailored to users' needs before they even initiate a request.

However, there are inherent concerns with creating these integrated, recommendation-based systems. One such concern is user control i.e., whether users will have the autonomy to manage how their information is shared.

A positive case of AI deployment in this area is Finland’s AuroraAI, a recommendation-based system that suggests public and private services to citizens based on their significant life events. In developing the platform, the Finnish government prioritised participatory ethical design and established an Ethics Board to conduct a 360-risk evaluation. The board raised transparency and control as primary concerns. To address these, the team integrated AuroraAI with Finnish citizens' digital identity (DigiMe), granting users full oversight of their own database and complete autonomy over when, how, and with whom their data is shared. Finland's solution demonstrates how users’ autonomy can be honoured in the pursuit of more intelligent systems—an approach aligned to the high standards of data governance observed by healthcare systems. 1

AI-Simulated Policy and Decision-Making: Trust but Verify

In the domain of policymaking, AI and digital twin technologies are enabling governments to better anticipate the impacts of their policies. A popular approach is through AI-powered agent-based modelling (ABM). ABM originally involves programming autonomous agents with simple 'rules' in a virtual environment to observe their behaviours and interactions with other agents and the environment. These simple rule-based agents can now be replaced by complex AI agents that closely emulate human behaviours, resulting in more accurate predictions.

However, the danger of these simulations is their ability to project a veneer of objectivity and precision—when they are in fact simulacra of reality and not reality itself.

In 2020, Salesforce developed an ABM – dubbed the 'AI Economist'— to identify a tax policy that optimises the equality-productivity trade-off. Using worker and policymaker AI agents—each with pre-determined goals and varying skill levels that can learn, strategise, and co-adapt flexibly in the virtual environment—they discovered a tax scheme that reduced the trade-off between equality and productivity by 16%, surpassing existing known standards. Impressively, the tax scheme also demonstrated resilience against tax gaming and evasion strategies.

Nonetheless, recognising the potential risks of such simulations, Salesforce commissioned an ethical and human rights impact assessment2 and took concrete steps to ensure the risks were mitigated. For example, they validated the tax model through 125 in-person games with 100+ US-based participants (and found that the outcomes were aligned to what the simulations had produced). To prevent users misusing the software, they only shared the simulation code with selected users who identified themselves, and clearly detailed the intended purpose, variables, assumptions, use cases and limitations of the model in a simulation card. Salesforce's cautious approach towards the deployment of their model underscores the importance of rigorous validation, transparency, and human oversight in dealing with AI-generated responses.

AI-Generated Datasets for Training and Analysis: Protecting Privacy

Generative AI can help sidestep sensitive data breaches by mass-producing synthetic datasets—such as medical or financial data—for training and analysis. Such datasets contain new data points that mirror the statistical relationships found in the original data but will have no associations to real entities. Therefore, it can be safely used for a variety of purposes without compromising privacy.

By leveraging synthetic data, organisations can mitigate the risks associated with handling sensitive information while still being able to derive valuable insights.

AI-generated synthetic data is already being deployed in a wide range of sectors, including healthcare and finance. For example, a health insurance company, Anthem, is currently working with Google Cloud to create a synthetic data platform that will generate approximately 1.5 to 2 petabytes of synthetic data on patients’ medical histories and healthcare claims. This synthetic data will be used to improve the training of other AI algorithms to better spot fraudulent claims and abnormalities in health records—all while keeping patients’ personal information private.

Nevertheless, care is still needed to ensure that synthetic data does not inadvertently reveal private data and that extreme outliers are not identifiable. By leveraging synthetic data, organisations can mitigate the risks associated with handling sensitive information while still being able to derive valuable insights and make informed decisions.

Lessons from a Cautionary Case

Responsible AI practices that build trust among stakeholders can help organisations to reap the benefits of AI. In contrast, failure to deploy algorithms responsibly may create harm, halt adoption, or even topple a government.

In 2021, then-Netherlands Prime Minister Mark Rutte and his entire cabinet resigned following the fallout from a flawed self-learning algorithm designed to identify childcare benefits fraud.

When implemented by the Tax and Customs Administration of the Netherlands, the algorithm led to tens of thousands of innocent families being accused of fraud. The accusations disproportionately targeted ethnic minorities and families with dual nationality. Families were also tagged for minor oversights such as missing signatures. Those flagged had their benefits suspended and were often forced to repay thousands of euros, plunging many into hardship and distress. The fraud investigations also had knock-on effects on their ability to access other services.

Aside from the reputational devastation to the government, the flawed algorithm also shook the public’s trust in the use of AI in government. Headlines like “This Algorithm Could Ruin Your Life” and “Dutch Scandal Serves as a Warning for Europe over Risks of Using Algorithms” emerged. This scandal is often used in warnings about ‘algocracy’— rule by algorithms.

The Netherlands’ experience highlights key questions that government leaders should ask teams in charge of AI projects:

- What steps have you taken to ensure the quality of your data, and is your dataset sufficiently representative?

In the Dutch case, officials trained the algorithm on 30,000 applications with inaccurate labelling. The files tagged as 'correct' mainly consisted of outdated applications, while the files tagged as 'incorrect' were sourced from a Tax Authority blacklist of 270,000 individuals who were categorised as potential fraudsters without evidence. The individuals on the blacklist were unaware they were on it and had no means to contest their inclusion. This flawed data labelling compromised the algorithm's integrity, resulting in inaccurate predictions.

- What features are unacceptable, and how are you auditing the AI model to ensure continued fidelity?

A feature may be prohibited because it is a socially unacceptable or even illegal consideration for a decision. In the case of the Dutch tax authority, one legally? prohibited feature was ethnicity. As AIs are very good at reconstructing features that we may forbid it to use, more frequent and careful audits could have caught the inappropriate use of discriminatory inputs.3

- What trade-off is the algorithm making, and are we comfortable with it?

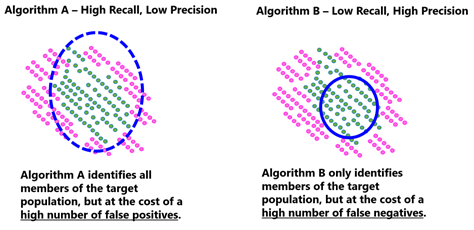

Algorithms generally have to trade-off between recall (the ability of the algorithm to identify all relevant cases) and precision (the percentage of all identified cases that are correct).

The acceptable balance between recall and precision depends on policy context. High recall (and poor precision) may be acceptable if the consequences of a false positive are not severe. For instance, an algorithm predicting potential exposure to a disease might mistakenly label someone as high risk, but the consequence might only involve taking a test to confirm or rule out infection. However, in the Dutch case, an algorithm that prioritises high recall may correctly identify all fraudulent tax cases, but also include many innocent people, with severe and politically unpalatable consequences.

- Who is responsible and accountable for the algorithm’s decision-making?

In the Dutch case, officers treated the algorithm’s predictions as verdicts rather than recommendations. There was no subsequent assessment by human tax officials. The decision-making responsibility was devolved to AI, but not the ultimate accountability, as the Rutte government learned the hard way. Leaders would do well to clearly designate and communicate the responsibility and accountability for AI output and its subsequent use.

- What ethical principles should apply here, and are we deploying such an ethical AI system?

For an enforcement model meant to detect fraud, the principle of human autonomy may not be as relevant as for service delivery with personal data. However, there are other ethical principles to consider. For instance, IMDA’s Model AI Governance Framework4 states that AI solutions should be explainable,5 transparent,6 and fair.7

In this case, the Dutch tax authority did not explain to citizens why they had been targeted for fraud investigations. Additionally, its system was opaque: people did not know that they had been subject to an algorithmic decision and found it difficult to challenge the decision. The system’s flaws emerged only because of investigative reporting and parliamentary inquiries. Finally, the system was deeply unfair since it unjustifiably discriminated against certain segments of the population.

Safety First, to Go Faster and Further

History shows us that safety features promote technology adoption. Modern cars come fully enclosed in steel with seat belts, automatic lights, and emergency braking. Additional regulations concerning speed limits and licensing further enhance driver and passenger safety. Higher risk technologies even include eject or abort features.

In the same vein, AI’s potential to transform government can only occur if it is adopted responsibly. Doing so will ensure the well-being of citizens, uphold ethical standards, and build trust in the beneficial capabilities of AI-driven governance.

NOTES

- The World Health Organisation put forward key principles in 2021 for the governance of healthcare data systems. They include autonomy – humans, not machines, should make final decisions; safety – AI tools should be continuously monitored to ensure that they are not causing harm; and equity – AI should not be biased against certain groups of people. Governance becomes critical to ensure the success of AI adoption without potential harm.

- The assessment was independently conducted by Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), a global non-profit organization. BSR uncovered some potential risks in the deployment of the model, including users over-relying on the outcomes produced, or misusing it for purposes other than what it was intended to do.

- At the same time, because AIs can reconstruct inappropriate inputs, agencies should still collect relevant data in order to check that their AI systems have not unintentionally factored in forbidden inputs in their predictions. That is, we won’t be able to tell if an AI is discriminating against racial minorities, unless we are able to check that they are not doing so.

- In addition to IMDA’s Model AI Governance Framework, leaders looking to implement AI solutions in the public sector can refer to GovTech’s Public Sector AI Playbook, which offers an overview of AI technology; a description of common applications; and guidance on using central AI products, developing internal capabilities, or procuring solutions.

- While AI is often likened to a "black box", explainability pertains to our capacity to offer rationale for specific outcomes, rather than to detail the inner workings of AI's decision-making processes. In the same vein, when we are asked to explain our decisions, we provide justifications for our choices, not a description of how our synapses interact with neurotransmitters. For more on the legal and technical dimensions of explanation, see Finale Doshi-Velez, Mason Kortz, et al., “Accountability of AI Under the Law: The Role of Explanation”, https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.01134.

- According to the OECD, transparency in AI involves, first, “disclosing when AI is being used”, and second, “enabling people to understand how an AI system is developed, trained, operates, and deployed in the relevant application domain”. Transparency heightens the chance that errors and misuse will be spotted. See OECD.AI Policy Observatory, “Transparency and explainability”, https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/ai-principles/P7.

- Fairness in AI is “the absence of prejudice or preference for an individual or group based on their characteristics”. Bias can emerge from different sources. For example, historical bias can be found in data that reflects existing societal disadvantages, representation bias stems from underrepresentation of small groups in data samples, and measurement bias occurs when an input into an algorithm does not accurately reflect the real world. See Mary Reagan, “Understanding Bias and Fairness in AI Systems”, 25 March 2021, https://towardsdatascience.com/understanding-bias-and-fairness-in-ai-systems-6f7fbfe267f3.