Varieties of Engagement in Government Citizen Interactions

ETHOS Issue 28, Apr 2025

Introduction: Engagement as a Growing Phenomenon

Theorists and practitioners of citizen engagement—used interchangeably here with related concepts such as deliberative democracy and participatory policymaking—often refer to the Athenian Oath:

“We will never bring disgrace on this our City by an act of dishonesty or cowardice. We will fight for the ideals and Sacred Things of the City both alone and with many. We will revere and obey the City's laws, and will do our best to incite a like reverence and respect in those above us who are prone to annul them or set them at naught. We will strive unceasingly to quicken the public's sense of civic duty. Thus, in all these ways, we will transmit this City not only, not less, but greater and more beautiful than it was transmitted to us.”

This oath was often recited by the citizens of Athens, Greece, more than 2,000 years ago. It is frequently cited as a timeless embodiment of civic responsibility and active participation by everyday citizens in the larger social, political and economic life around them.

Several ongoing projects (see box story below) that embody this same spirit of empowerment and agency by citizens, community groups, businesses and other stakeholders—in a climate where governments face declining trust in their ability to deliver services and reliably meet stakeholder needs.

Recent Examples of the Growing Global Trend in Citizen Participation

- The New Citizen Project led by Jon Alexander in the UK, which aims for individuals to once again see themselves as "citizens", rather than "subjects" of top-down authority or "consumers" of products and market forces1

- Involve, a UK charity focused on fostering public participation in policymaking2

- Taiwan's G0v (gov-zero) project, a decentralised civic tech community with information transparency, open results and open cooperation as its core values3

- Participatory budgeting projects in Brazil, which began in the city of Porto Alegre, one of the most populated cities in South Brazil—where budget allocations for public welfare works have been made only after the recommendations of public delegates and approval by the city council4—and have since been applied in Europe, China and elsewhere.

- Deliberative polling projects spearheaded by Stanford academic James Fishkin and his Deliberative Democracy Lab5

- Citizen Assemblies in Ireland that have discussed gender equality, biodiversity loss and the state of the Irish constitution6

- The city of Hamburg's Urban Data Challenge, which made available exclusive public mobility data as part of a competition of ideas where citizens, universities, businesses and other organisations could suggest innovative concepts and proposals for micro-mobility flows in the city7

- Citizen conventions in France which have discussed a range of issues, including climate, end of life, and how to respond to the Yellow Vest (gilets jaunes) grassroots movement, which was initially motivated by rising crude oil and fuel prices, a high cost of living, and economic inequality8

More and more organisations are also initiating or intensifying ground-up participatory approaches:

- Democracy Next9 led by Claudia Chwalisz, which has worked across Europe and OECD countries

- The Kettering Foundation,10 Centre for New Democratic Processes11 and National Coalition for Deliberation and Dialogue12 in the USA

- DemocracyCo13 (which also features in this issue) and the New Democracy Foundation,14 in Adelaide and Melbourne, Australia, respectively

Singapore is no stranger to such developments, with examples including:

- The foundations of a citizen Feedback Unit (subsequently renamed REACH)

- The Our Singapore Conversation (OSC) process in 2012

- The Singapore Together movement and Alliances for Action which emphasised partnerships between the government and other stakeholders in business and the community

- The Emerging Stronger Together project during the COVID-19 pandemic

- The recent Forward SG effort spearheaded by Prime Minister Lawrence Wong

The establishment of the Singapore Partnerships Office (SGPO) in the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY) has consolidated these efforts to ensure a structured, coordinated approach to citizen engagement and building partnerships between government agencies and other stakeholders.

Unified Movement or Varied Phenomena?

It is tempting to see the developments as part of a broad-based, consistent, possibly even global trend—leading ineluctably to more and deeper engagement between citizens, other stakeholders and public agencies.

But the reality is much more murky, with a wide range of outcomes and configurations of how governments and citizens interact. Not all governments, and not all communities, businesses and other stakeholders, participate evenly in deliberative efforts.

Why not?

Many political scientists might address this by looking at how such engagements are structured, organised and institutionally supported. But what if these deliberations do not even happen in the first place, because they did not get approved to proceed, or were aborted at a nascent stage?

I suggest a different explanation for why such projects happen or not, and then whether they succeed, based on what some economists call 'micro foundations' or 'micro motivations': Are the individual human beings involved willing players, or are they more reluctant participants in deliberative activities?

For instance, the staff of a government agency could be willing players and advocates for participatory processes. They could be entrepreneurial, believing in the richness and value of deliberative activity, recognising that governments can have biases and other limitations, and not possess a monopoly on good ideas. Such agency officials may have undertaken successful participatory projects before, and built mutual trust with relevant stakeholders—making them more willing to take on the risks of experimenting with such consultative and co-creative approaches.

Conversely, a government's staff might be unwilling players: risk averse about the potential resource costs and other downsides of deliberative projects, including whether such efforts might generate expectations among citizens that all their recommendations would be taken on board, or that all decisions would henceforth be made in a participatory manner.

In some instances, government officials might have tried but been disillusioned by previous attempts at deliberation. A politician I interviewed remarked that he was "once bitten, twice shy" about engagement processes, and was reluctant to undertake new efforts "because I was so badly burned before" when expectations from an engagement process spiralled out of control and led to ever increasing demands from participants. Even more fundamentally, government officials might simply believe that they should be what New America Foundation CEO Anne Marie Slaughter has described as a "control tower",15 clearly calling the shots in most interactions because they can access superior information.

Similarly, stakeholders in a project—whether citizen, community groups, businesses or some combination of them—could occupy a spectrum of willingness. They could be naturally and instinctively engaged in civic participation, believe in the ethos of the Athenian oath and see their role as active contributors to democratic life, as well as active students of democracy who learn from the mutual interactions of a deliberative process. Or they could be unwilling—apathetic and disengaged on issues—or disillusioned with previous deliberative efforts that they might have attended and found to be superficial or merely rubber-stamping predetermined decisions.

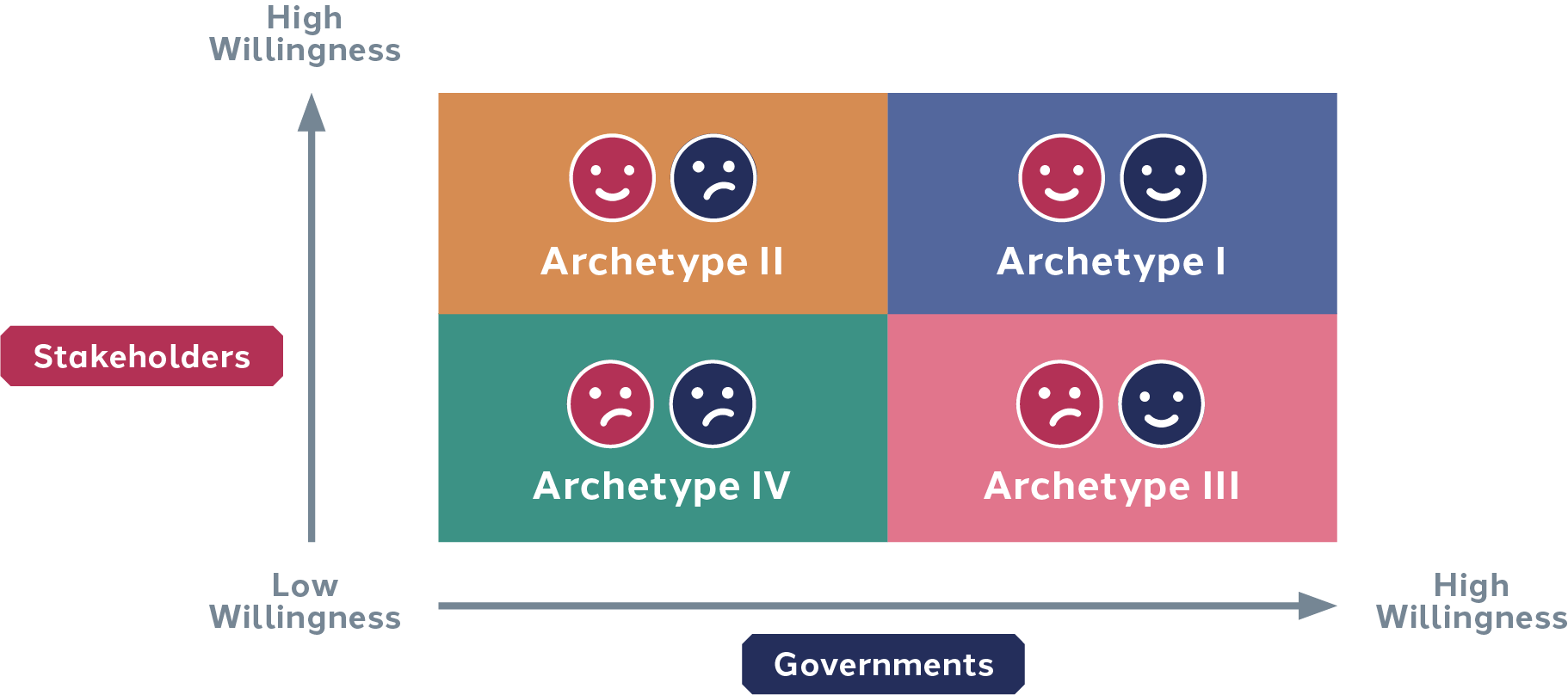

In any case, participant motivations need not be either binarily willing or unwilling but could instead occur along a continuum of willingness and unwillingness. Individual projects could be situated anywhere in the 2x2 space outlined in Figure 1, but for ease of analysis, I discuss four broad archetypes.

Archetype I involves both willing government and willing stakeholders—leading to rich outcomes from mutual deliberation and engagement. There can be collectively useful outcomes, at the system-level, and mutual learning between both parties.

Archetype IV is the direct opposite, with unwilling parties on both sides. This leads to participatory processes that are either short-lived or do not even take place, getting cut off at the early stages of approval or recruitment of participants.

Archetype II, with more willing stakeholders and less willing governments, may often end up being marketed as "bottom up" or "grassroots" movements. Such projects lack the formal imprimatur of involvement by, or at least support from, government agencies.

Archetype III, with more willing government agents but less willing stakeholders, can often be stylised and ritualised deliberative processes, where discussions are somewhat staged, with pre-set questions and avoidance of more spontaneous discussions. They may take the form of formal town hall discussions, with government officials sharing pre-prepared material and engaging in cursory Question & Answer sessions. Citizens and other stakeholders may cynically regard these as political theatre meant to endorse predetermined government decisions rather than platforms for genuine conversation and debate.

Nash Equilibria and Other Nuances

Several points about the four archetypes are worth noting.

First, from a game theory perspective, the payoffs to each set of actors (i.e. governments and other stakeholders) may be such that, under conditions of uncertainty about each other's motivations, it is always 'rational'—more convenient, more efficient in the short-term, and more logical according to strict cost-benefit analysis—to assume that the 'other side' is unwilling. If this is the case, then the Nash Equilibrium will tend towards the sub-optimal Archetype IV. This is unless there are other factors demonstrating the willingness of each side to initiate and (crucially) sustain an engagement effort. Perhaps successful examples of citizen participation are in fact an exceptional minority among countries globally, rather than a growing trend.

Second, the boundaries of the 2x2 matrix could well be porous. Within a given polity, different deliberative projects could occur in different quadrants, depending on the government agencies and stakeholders involved. A single deliberative process could also end up inhabiting different quadrants at different times, as circumstances evolve (and the protagonists involved change, for instance).

Third, a system as a whole can be more resistant and unwilling, even if individual citizens or small groups of officials are keen. Such personalities, sometimes described as policy or civic innovators/entrepreneurs, could well be an active minority that ends up sidelined by more sceptical and unwilling counterparts.

Managing these dynamics is key to maximising the opportunities and minimising the challenges of each archetype—as well as avoiding the trap of the sub-optimal Nash Equilibrium.

Implications for Participatory Practice

Game theorists often point out that sub-optimal Nash Equilibria are best avoided when players understand that they are in a repeated game, not just a single scenario where win-loss outcomes are once-off and immutable. They also emphasise the role of commitment mechanisms, whereby each actor can make clear and irrevocable commitments to strategies that, if chosen by both, will lead to better collective outcomes.

Relational approaches could prove beneficial, if they allow public agency staff and stakeholders to get to know one another better and give one another the benefit of the doubt when dealing with uncertain outcomes.

Common to both these approaches is the importance of relationships—where each player sees the other not as just a strategic adversary, but someone with whom mutual interests and trust can be cultivated. Such relational approaches could prove beneficial for deliberative outcomes, if they allow public agency staff and stakeholders to get to know one another better and give one another the benefit of the doubt when dealing with uncertain outcomes. It is also important for each group to check their biases and suspicions about the other. If such interactions happen with sufficient regularity and substance—e.g. through regular meetings where information about priorities, plans and programmes are exchanged—they could provide a critical bedrock for deep and substantive deliberative programmes in the medium-term.

Government officials can contribute to realising Archetype I by making clear their intent and the unique selling points of the whole deliberative process, so that participants are aware of what they volunteer for. Governments should appreciate that even with the best of intentions, they wield significant power and are engaged in a highly asymmetric relationship with citizens. Moving towards Archetype I will involve significant sharing of information, particularly on the policy intent of proposed changes or ideas under discussion. Citizens, on their part, can consider where they might exercise autonomy and agency and contribute actively to processes where outcomes are not determined by government agencies alone.

As with many interactive engagement efforts, facilitators play a key role. They should be sensitive to power dynamics between stakeholders and agencies that commission such efforts, even going to the extent of calling out potential power differentials when recruiting participants, and actual power gaps during a process. If necessary, time should be set aside to discuss and unpack issues of willingness—especially if there is an underbelly of reluctance on the part of either the commissioning agency of a project or its stakeholders.

Making Technology Work for Participation

Savvy officials and civic stakeholders can ensure technological tools are deployed and managed for the most positive results possible.

|

|---|

| For Archetype I projects (willing government and willing stakeholders), new information-sharing tools can build up public understanding of an issue even before deliberation occurs: such as through shared files or secure discussion platforms. Online communications tools like Zoom can facilitate relationship-building among citizens, and between citizens and government, including outside deliberative sessions—allowing future champions and enthusiasts of deliberation to be nurtured. Such online tools were used extensively during Singapore's Alliance for Action initiative on tackling online harms, especially against women and girls, in an effort named "Project Sunlight". Technology (and Artificial Intelligence in particular) could also improve the quality of the deliberation itself: through support features like real-time language translation, synthesising expert input and points of consensus in otherwise intractably large volumes, use of AI mediators when participants have conflicting views, and enabling deliberations at scale through digital facilitators who might, for instance, pose some pertinent starting questions on an issue. |

|

|---|

| For Archetype II projects (willing stakeholders, unwilling governments), technology can be used to research and highlight successful international examples, and to enable simulations and role play to provide immersive personal experiences and overcome initial scepticism. Allowing potentially unwilling officials to experience a deliberative process first-hand, and/or to learn from others' successes, could tip the balance in favour of giving a project a chance to prove itself. An experiment in Southern Chile used role-playing to evaluate how residents affected by high concentrations of fine particulate matter perceive the problem and debate possible solutions. Digital technology allowed participants across six mid-sized cities to assume the role of advisors, as part of which they had to prioritise between a series of mitigation measures and reach a consensus with other advisors.16 |

|

|---|

| Archetype III projects (willing governments but unwilling stakeholders) could gain from technology-enabled low-cost ways to engage lightly at first, e.g. through prototypes and beta versions, as well as simulations that can be cost-effectively repeated. These could help prove to citizens that the engagement projects are worth participating in, and could support participant selection for eventual, full-blown deliberative processes. A field experiment in Germany showed how technology can enhance a process termed "democratic persuasion".17 During the COVID-19 pandemic, citizens were invited via Facebook to participate in one of sixteen Zoom town halls, to engage in discussions on pandemic politics with members of German state and federal parliaments. Each representative hosted two town hall meetings, with random assignment to a condition of 'democratic persuasion' in one of the two town hall meetings.18 |

|

|---|

| Type IV projects, where both sides are unwilling, will probably be the toughest nuts to crack. Mutual scepticism may make them difficult to begin in the first place. Here, the connective potential of digital technology may help: pockets of enthusiasts can use the social web and other networking tools to locate one another, exchange ideas and best practices, and convene online discussions. While these do not completely replace deeper, in-person interactions, they can be a useful start, especially if such interactions lay the foundations for deeper inter-personal engagement subsequently. Over time, such efforts can hopefully catalyse a move away from Archetype IV to Archetype I, since the boundaries across the archetypes are porous and unhealthy equilibria need not be the permanent state. While this may not be easy or quick to realise, the possibility of a shift is real. There are nascent but promising examples of these, including in conflict-riven societies like Colombia. The Territorial Dialogue Initiative19 uses a stakeholder dialogue methodology to generate spaces for collaborative co-creation and technology-enabled advocacy in response to local challenges. The Civic Laboratories project creates spaces, including some online, for participatory budgeting, with up to 50% of the budget in Bogotá's 20-constituent municipality Mayor's offices being dedicated to citizen-led projects. |

Digital Technology as Participatory Enabler

Digital technology has been much vaunted as a potentially transformative force in politics and governance, including in the space of engagement, deliberation and participation by non-government stakeholders. But technology watchers also know that its effects are seldom homogeneous across sectors and issues.

Conway's Law, a theory of Information Technology created by computer scientist and programmer Melvin Conway in the 1970s, asserts that "Organisations, who design systems, are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organisations."20 This implies that, far from being inevitably transformative, technology can sometimes be adopted in ways that reinforce or even entrench the prevailing culture, history and approaches in an organisation.

Technology makes hierarchical and bureaucratic organisations more hierarchical and bureaucratic, while it is adopted by more democratic, distributed and decentralised systems in ways that intensify those qualities.

For deliberative projects, a key question is what technology does not change. This could include the different underlying logics and motivations for groups in each quadrant of Figure 1—digitalisation may well make unwilling groups more unwilling to deliberate (e.g. due to fears of information being used in ways that erode government security or personal privacy), or make willing groups even more willing (e.g. because of the scope for richer information flows and cross-pollinated ideas).Technology will also do little to change any asymmetries in power dynamics when different groups interact (e.g. protocol-consciousness when politicians participate in engagement events can play out equally in a Zoom meeting and in person), while there will be a continued need for facilitators to design the experience of a deliberative process even on a digital platform.

Scholars and practitioners alike point to the potential of participatory processes to enrich both political and civic life. In many of the examples cited at the start of this article, deliberative platforms have led to better ideas for societies and cities as a whole, while also proving edifying and educational for individual participants. However, these conclusions are far from necessary or foregone, since they depend critically on the micro-level motivations of the individuals involved, both within and outside governments. Addressing these motivations directly, through both analogue and technologically-enabled means, could take deliberative projects to new levels of achievement, and be critical enablers to realising the vision of the Athenian Oath in ways that are fit for our times.

NOTES

- https://www.newcitizenproject.com/

- https://involve.org.uk/

- https://g0v.tw/intl/en

- https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/600841468017069677/participatory-budgeting-in-brazil

- https://deliberation.stanford.edu/what-deliberative-pollingr

- https://citizensassembly.ie/

- https://thenewhanse.eu/en

- https://isps.yale.edu/news/blog/2024/04/governing-citizens%E2%80%99-assemblies-lessons-from-france-and-beyond

- https://www.demnext.org/es

- https://kettering.org/

- https://www.cndp.us/

- https://www.ncdd.org/

- https://www.democracyco.com.au/

- https://www.newdemocracy.com.au/

- Slaughter, Anne-Marie. "America's Edge: Power in the Networked Century." Foreign Affairs 88, no. 1 (2009): 94–113. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20699436.

- À. Boso, J. Garrido, L. K. Sánchez-Galvis, et al. "Exploring role-playing as a tool for involving citizens in air pollution mitigation urban policies," Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 447 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02686-2.

- The process involved actively making the case for democracy and discussing democracy's inherent trade-offs while engaging existing doubts and misperceptions among citizens.

- A. Wuttke and F. Foos, "Making the case for democracy: A field-experiment on democratic persuasion," European Journal of Political Research (2024), https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12705

- https://oecd-opsi.org/innovations/territorial-dialogue-initiative-idt-yumbo/

- Conway's Law gained popularity after being cited in the iconic book The Mythical Man-Month. See Brooks, Frederick P., Jr., 1931-2022. The Mythical Man-Month : Essays on Software Engineering. Reading, Mass. :Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., 1982.