Finding Common Ground for Partnership

ETHOS Issue 28, Apr 2025

What is the Common Ground project and what does it aim to achieve?

I had been a cultural change strategist for some two decades, working with people and organisations in different contexts. MCCY approached my outfit at the time, The Thought Collective, to consider taking over a vacated state-owned community building that was not being fully utilised, to run as a kind of experimental civic centre. We agreed, because this felt aligned with our own interest in exploring how to shift aspects of Singapore culture that perhaps needed a relook.

The idea was to set up a civic centre to support the community's ability to explore social concerns. The project scope involved bringing in resident partners to co-locate in the building. We were looking for organisations based in Singapore, non-profit or otherwise, to take up at least a three-year stint. They had to be concerned about something in society, and also have a professional skillset to contribute.

One of the narratives I try to counter through this project is the notion that a social concern must involve organisations or figures associated explicitly with social content or causes. This is because there are other significant aspects that could have an impact on social issues.

For example, a resident partner who came on board early on is Studio Dojo, a transdisciplinary consultancy team that does not fit the typical profile of an outfit in a civic centre. They see many organisations trying to solve problems from the mindset of a single discipline, which then runs into problems along the way. Instead, they apply a range of skillsets to issues: from design thinking to leadership development and futures thinking. To me, this is also a way to address social concerns.

Another of our resident partners, Daughters of Tomorrow, is a non-profit organisation that facilitates livelihood opportunities for underprivileged women, and supports them in building financially independent and resilient families. They complement the work of training and workforce-related agencies. By collaborating with key partners and employers, they influence organisations to consider workplace schemes that make regular employment more possible for the less privileged.

A more recent partner, Kontinentalist, does data storytelling. Their social concern is to help people be more data-literate, and more skilled at interpreting data. They publish data-oriented stories and conduct public education on how to use data. They are also Asia-centric, to counter a prevailing dearth of data from and about Asia, and are also strongly socially focused, believing that data should be more inclusive.

Common Ground is built on partnerships. How do you engage with the government, partners and other stakeholders?

Our partnership with MCCY began with a mutually agreed set of tentative key performance indicators (KPIs), but none of us quite knew what the project or its outcomes would look like in detail: in my experience, this is quite unique. We started with a sincere willingness on both sides of the table to give it a go, and a lot of mutual trust. The Government has given us a lot of leeway for us to explore possibilities. While we still need to be self-sustaining, the state has provided a generous amount of funding to cover the rental of the property and some expenses.

Partnerships are like a marriage: things look rosy at the start, until you get into the weeds. After that, all you have is your trust in each other, and how you talk to one another to work things out. For instance, the project kicked off in 2019 when the COVID-19 pandemic was taking place. Our government partners were understanding and did not insist that we keep to our agreed-upon initial KPIs regardless of the crisis. Had they done so, it would have compromised our mutual trust. Instead, we found a way forward together.

A similar climate of trust and flexibility extends to our relationship with our resident partners. This is not a master tenant and subtenant relationship: the concept we settled on is a membership. Via a membership fee, our resident partners have access to affordable spaces for their daily operations as well as to gather people and build networks. They also receive developmental hours that can be used for skills development or to get support from our consultancy team—for instance, they could use this time to have me facilitate a conversation with their board of directors.

We are learning to do better over the years, based on how our members use our resources. When we started, our proposition to members was more unstructured. From observation, we found that such an approach is not always effective, depending on the profile of our resident partners. Going forward, we are planning to offer a more structured approach, with interventions based on the key issues we have observed recurring across our resident members' work.

Partnerships are like a marriage: things look rosy at the start, until you get into the weeds. After that, all you have is your trust in each other.

From your experience, what are some challenges faced by organisations seeking to contribute to social concerns?

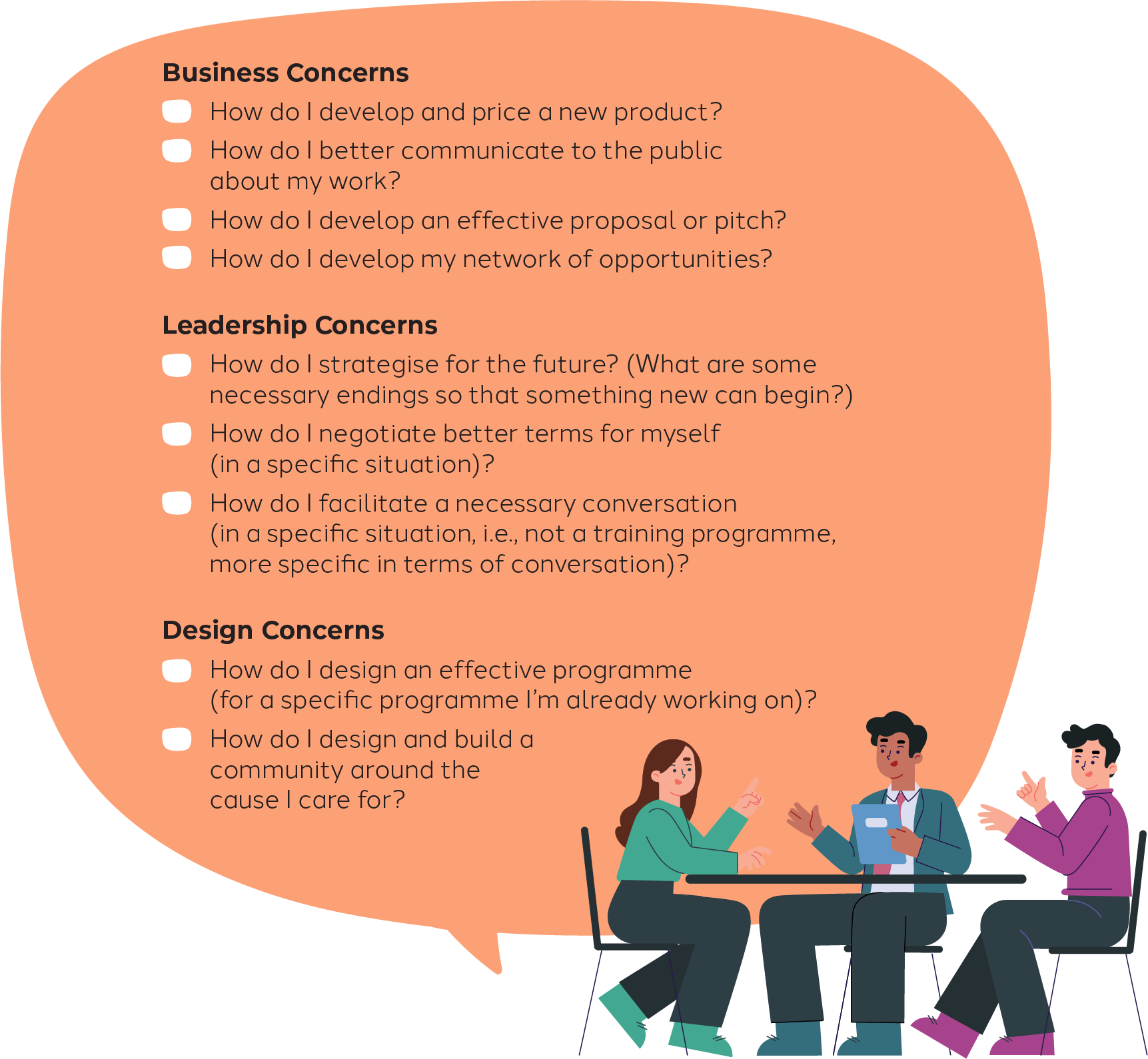

This work has given me a lot of empathy for the variety of organisations trying to do something meaningful. One insight is that some do certain parts of the work better than others. But we have noticed that no one can be very effective if they cannot resolve nine key questions (see figure below). Such questions include practical ones, such as how to price your product or service, or what sort of entity they should be.

One of these difficult questions is that of when to end. This is important to consider at the beginning. For instance, when we conceived this project with MCCY, the idea was that it would be time-bound—limited to ten years—and not go on forever. But this is a crucial question to also ask in the middle: when an organisation reflects on the way in which it has addressed an issue and whether it is indeed the best way to proceed.

Many incubator-like spaces are all about the beginning and middle of things. Nobody wants to talk about the end. But sometimes, an ending is necessary so that something better can happen. It could be the end of a certain approach to doing things, or a business partnership, or recognising that one is not the best person to be playing a particular role. All this involves a grieving process, which takes time and trust.

Nobody wants to talk about the end. But sometimes, an ending is necessary so that something better can happen.

In a sense, this civic centre began at peak loss, having started during the pandemic when many purpose-driven organisations had to face quite abrupt ends because they could no longer sustain their activities. We recognised that in many ways, we and some of our resident partners were sheltered by our situation, with projects that were not dependent on gatherings, for instance. But others had to make hard decisions during these tough times. One partner jointly decided as a team to stop and go out to try and earn a living before circling back to their work later.

How should we be thinking about designing KPIs for work with social value?

The social sector is impactful but can sometimes struggle to explain exactly how and to what degree it makes its impact. In a sense, this is one of the aims of this civic centre project: to discover what works and what does not, and to iterate as we go.

We are starting to converge on what are some of the broad buckets of KPIs that matter. The first has to do with awareness. The second is around skills-building. Then there is a set that is needed most, but is also most complex, which is about how to measure social value.

One article1 has argued that it is more meaningful and practical to track inputs and activities that support collaborative learning and adaptation, since we may not truly know how things turn out until later. Tracking input means paying attention to the quality of thinking and design that goes into an initiative and trusting that good input has a higher likelihood of resulting in good outcomes down the road.

One grievance many practitioners share is that they feel they are doing a lot of good work, so why must they be tracked at all rather than being trusted to carry on with it? Once they accept that some indicators are necessary for good governance, their next concern is whether the instruments used to do this tracking are too blunt—for example, only tracking the attendance of people who showed up at their event. But we do need to ask: If we want good work to scale, what does that look like? Do we mean big numbers of people reached? If not, are there other ways in which we can articulate quality and progress in a way that meets the needs of funders, practitioners and the community?

Coming up with good KPIs is a difficult thing to do and involves tough, complex questions. Such questions must be considered in a relationship where all parties trust that everyone has a genuine stake in wanting to figure out how best to make it work. It can feel oppressive, unfair, or unhelpful when the people on the ground are left out of this conversation.

Good KPIs cannot be developed by people who are not doing the work. They can only come out if you are both doing the work and observing the work, which is the position I find myself in. A traditional consultant stands at a safe distance from the world and, from that zoomed-out vantage point, observes and judges it. You need someone to perform that role, but you also need the perspectives of those who are actually labouring in the trenches and suffering the actual conditions that arise from the goals they have committed themselves to.

Realistically, you do need to invest a significant amount of time to examine and review KPIs as you go along, to ensure that they continue to meaningfully track how well you are actually doing in the areas you care about. It is also one thing to come up with KPIs, and quite another to design them so that people are willing to put up with them.

The gold standard would be if stakeholders look at the KPIs and all agree that these make sense and so they do not mind tracking the data, because it is intuitively in alignment with their goals, not excessively onerous to collect, and affirms the work that has been done.

To design good KPIs that are also practitioner-centric, you need three capacities in balance. You must be able to do the work and understand the nuances of doing it—so you know what is worth tracking. You need a good emotional feel for what the impact of the tracking is: not just on the practitioner, but also the people being tracked. And you need the cognitive ability to articulate what all this means. This is a big ask for people who are just interested in doing the work itself, but it is necessary.

It is one thing to come up with KPIs, and quite another to design them so that people are willing to put up with them.

How can we continue to grow and nurture an active citizenry?

I tend to take the view that citizens are already active in something—just not necessarily the things the state wants them to be active in. So, we need to be curious about what they have been active in: we may be pleasantly surprised to find that it is in alignment with what we need.

We need to first recognise the ways in which those outside the usual circle of social causes and non-profit organisations, including the person on the street, are already being active. For example, some young people may be actively trying to stop a friend from self-harm, but they may not be signing up for official activities. There could be millions of different people and activities out there not captured by the data as being 'active'.

The question is: how can we get an entire people to be vested in the good of everyone? To do this, we need to look beyond our usual scope and come together, the public and the government, to look at what is working well and what is not, which will be different in many areas. We should not begin with an assumption that we already know best what the issues are, or how best to address them.

The key is whether we can have relationships with enough trust that we can be honest about our experiences, frustrations and concerns. Otherwise, people may hold back and simply voice grievances or discuss only parts of their experience that they think officials want to hear.

What we have done at Common Ground will have been worthwhile if we manage to give our partners and stakeholders a taste of what it is like to operate in a climate of mutual support and trust. A tremendous amount of trust has been extended to us in this project and in turn, I feel more trust in government for being prepared to make such an initiative work. We have experienced genuine care and sincerity thus far—not just for us as human beings, but also towards the work and the process.

My hope for civic engagement in Singapore is that we learn to trust not just in particular individuals, but in the social sector as a whole: that it consists of people who sincerely care about issues and are striving to address them, on both sides of the table. If we can reach a point where all parties feel this way—where we trust that everyone involved in a civic initiative cares about the quality of the work and the integrity of relationship, and can call one another to account—we will be doing well.

NOTE

- https://toby-89881.medium.com/explode-on-impact-cba283b908cb