Empowering Communities Through Co Vision, Co Action and Co Learning

ETHOS Issue 28, Apr 2025

In Singapore, the social sector (also referred to here as the people or non-profit sector) is experiencing a number of significant trends. These include resource considerations such as greater scarcity, overserved and underserved populations, resource matching issues, as well as a growing number of multifaceted and multidisciplinary challenges, from a rapidly ageing society to digital transformation and more. At the same time, the citizenry has become more able and willing to be more involved in public issues, shifting the emphasis on government directed interventions to more ground-up community engagement and participation.

Traditional community engagement strategies, which are more top-down directed, must evolve to contend with these new priorities and pressures. In doing so, the sector benefits from looking outside itself to take in new ideas. In this light, modes of co-creation and co-delivery have emerged as opportunities for Singaporeans to be more actively involved in planning and delivering the services they receive. Co-creation is about planning together with citizens and co-delivery is about doing and learning together with citizens. Such approaches are aligned with the aspirations presented in the Forward Singapore report released last year,1 highlighting the importance of working with the general public to keep the Singapore dream alive and well.

HOW TO CO-CREATE AND CO-DELIVER WELL

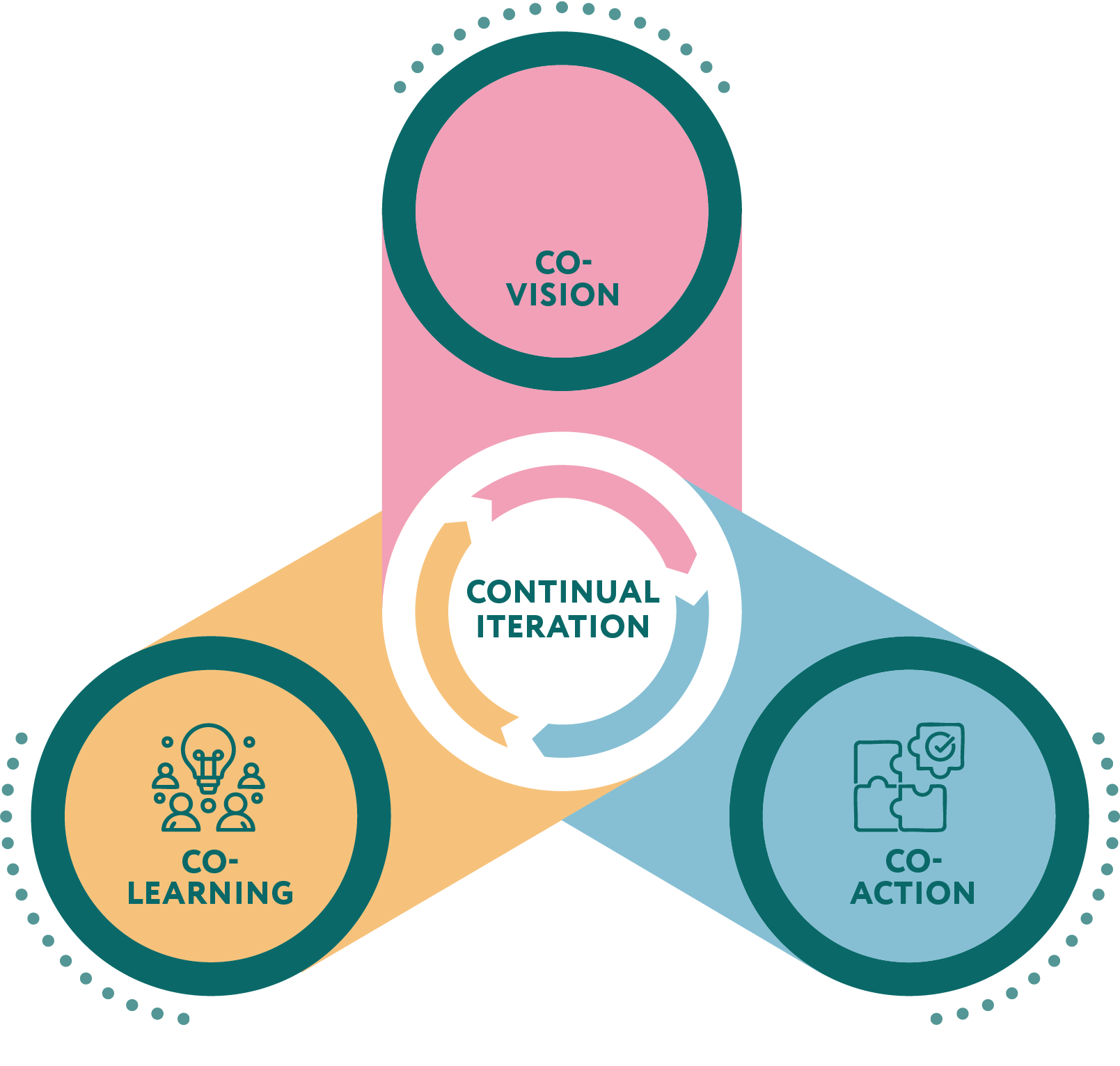

How can stakeholders in the social sector make the most of co-creation and co-delivery as modes of engagement? To realise these strategies well in practice, my research into Singapore's social sector suggests that an iterative, three-pronged framework that involves co-vision, co-action and co-learning (Figure 1) is effective.

CO-VISION

To co-vision is to create a common purpose. Traditionally, organisational leaders decide the vision in a top-down manner, which other stakeholders (such as the rest of their organisation) are then meant to adopt. However, while this approach may appear quicker to implement, it does not engender a sense of ownership, as the majority of stakeholders have not participated in creating the vision.

At the other end of the spectrum, a 'bottom-up' approach to co-visioning can foster a strong sense of shared ownership for the vision—but can take much longer to align the many different perspectives among community stakeholders.

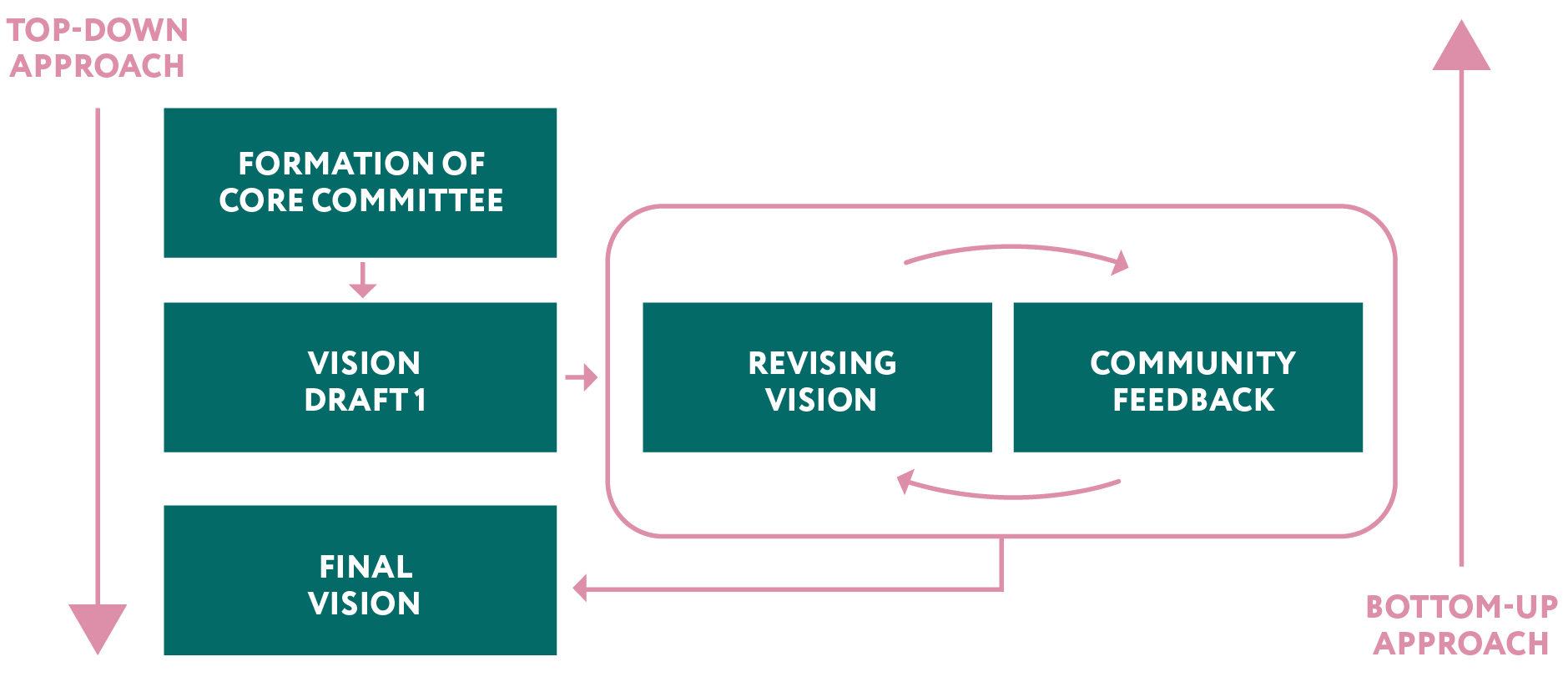

A pragmatic approach draws on the benefits of both top-down and bottom-up approaches (Figure 2):

- A small but diverse core committee of people, comprising representatives of all stakeholders, is formed to draft the vision for the programme. Care is taken to ensure that the committee members are truly representative of the respective stakeholder views, and to ensure that the committee is as diverse as possible.

- Design thinking methodologies might be used to expedite the initial visioning process. Once the first draft of the vision is produced with input from all committee members, it is offered to the broader community for their input.

- During the community feedback sessions, participants are encouraged to diverge in thinking before converging to the best few ideas. It is important in the convergence process to emphasise aligning concepts and ideas rather than to fixating on the exact words used. These collective thinking sessions should be conducted to ensure that as many possible ideas can be generated, allowing for the best version of the draft vision to emerge.

- After the feedback session, the vision and the community's inputs are given back to the committee for further deliberation. This iterative process is repeated until at least 30% of the community is satisfied with the vision. My research on organisational transformation in the sector suggests that this is the critical threshold beyond which the vision gains enough momentum to spread throughout the target population.

CO-ACTION

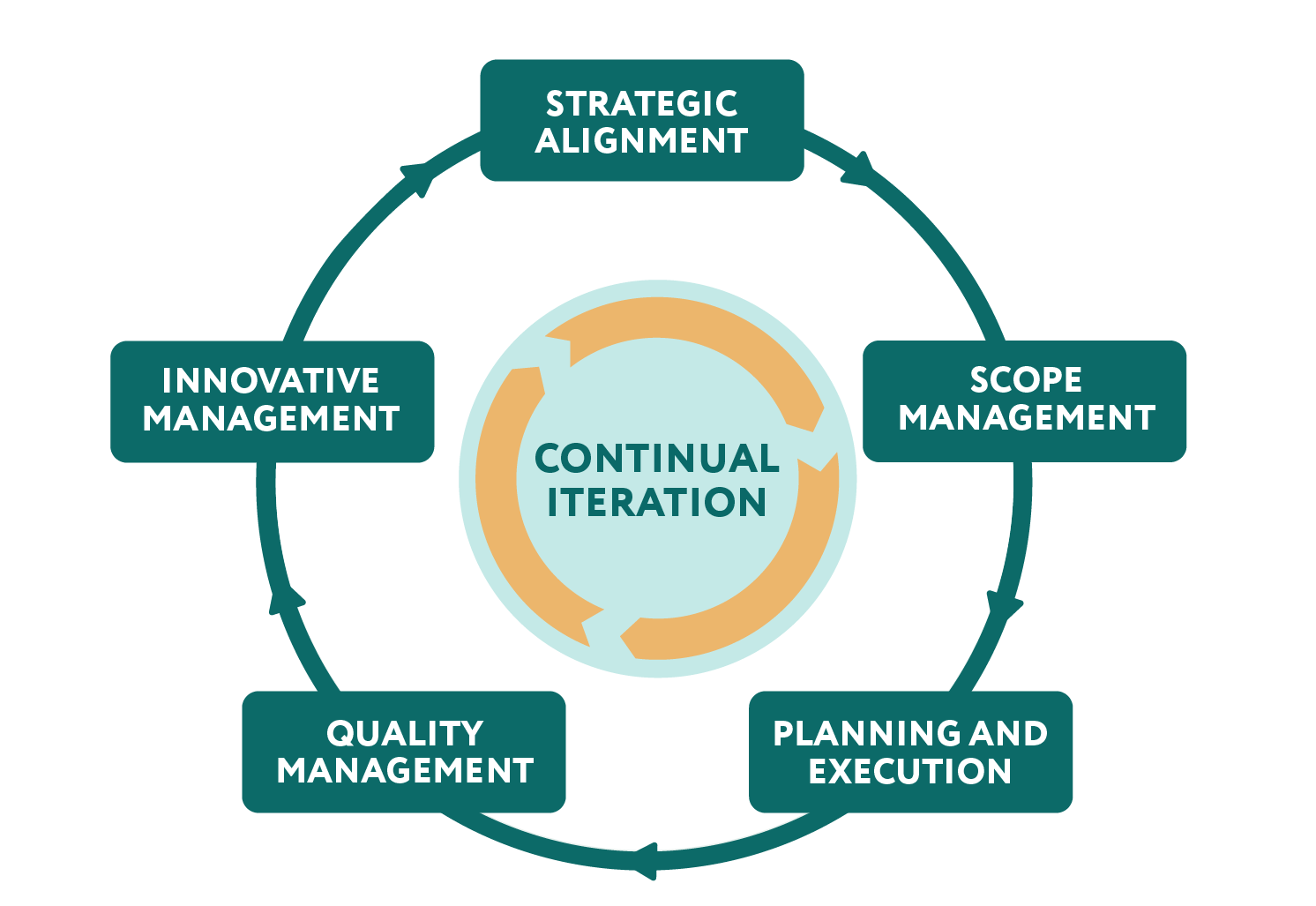

Co-action is about doing things together in a concerted effort to achieve shared goals. This can be achieved using an integrated programme management framework.

Such a framework enables the stakeholders co-participating in a project to work in unison, much like a successful football team would:

- For a football team to be successful, its players must operate with a clear common objective in mind: to score goals on the opponent's side. Similarly, strategic alignment enables the working group to have clarity on their mission and the purpose of the project, ensuring that the project serves the community's vision and objectives.

- A football team consists of various roles, but most players are able to switch roles easily as they understand one another's function on the team. Likewise, scope management allows the working team to understand both their own responsibilities as well as those of their fellow team members by defining objectives and deliverables for the project. This builds agility into the team, allowing members with the right skills to cover for each other's roles when required.

- While players seem to be moving in random patterns in a football game, their movements are in fact guided by an overarching game plan. Good planning and execution enable this adaptability and flexibility to take place in co-creation and co-delivery programmes, by providing an overarching strategy that guides the team's work, enabling them to work independently from each other while still being able to stay on track.

- Before each football game, a team discusses their plans for the game ahead, including how many goals they aim to score. Similarly, quality management allows for project teams in the social sector to operate in a similar way, by establishing and monitoring KPIs to ensure that actual deliverables meet requirements established earlier in the project.

- Football teams conduct practice games with opponents to hone skills and develop new strategies for upcoming competitions, enabling teams to respond more quickly to their opponents during actual matches. In a similar manner, innovation management allows social sector project teams to quickly respond to new opportunities. This includes a risk management approach to determine ahead of time what kinds of risks the project is able and willing to take.

CO-LEARNING

Co-learning is about building a system of continual improvement by closing the learning loop within a co-creation and co-delivery partnership of stakeholders. This ensures that lessons from the project are ingrained in the system, helping future iterations of the project do better. A learning loop framework can help boost confidence because partners and stakeholders have a foundation to work from, rather than feeling like programmes have to begin from scratch with every iteration.

Co-learning allows co-creation and co-delivery teams to leverage what has worked in the past, while also trying out new ways of doing things. Learning feedback loops help the team identify when project results deviate from desired outcomes, and then to take appropriate correction action. This enables new solutions to be quickly rolled out and reviewed to improve the next iteration: allowing for greater project agility and rapid prototyping in an increasingly volatile and fast-changing environment.

Collaborative learning with stakeholders across the different sectors in society, both for strategic and operational, ground-level issues, will become increasingly relevant. As public issues become more multifaceted and complex, they will require not just whole-of-government coordination but also whole-of-society understanding, innovation and action.

Co-learning with stakeholders across and outside the public sector can not only surface fresh perspectives and ideas, but also engender greater trust in government, foster greater understanding and ownership of complex issues, as well as acceptance of trade-offs and different possible outcomes. The paradigm shifts from a know-all government with the sole responsibility to resolve all problems, to one where all of society are learning together to grapple with the challenges we must face together.

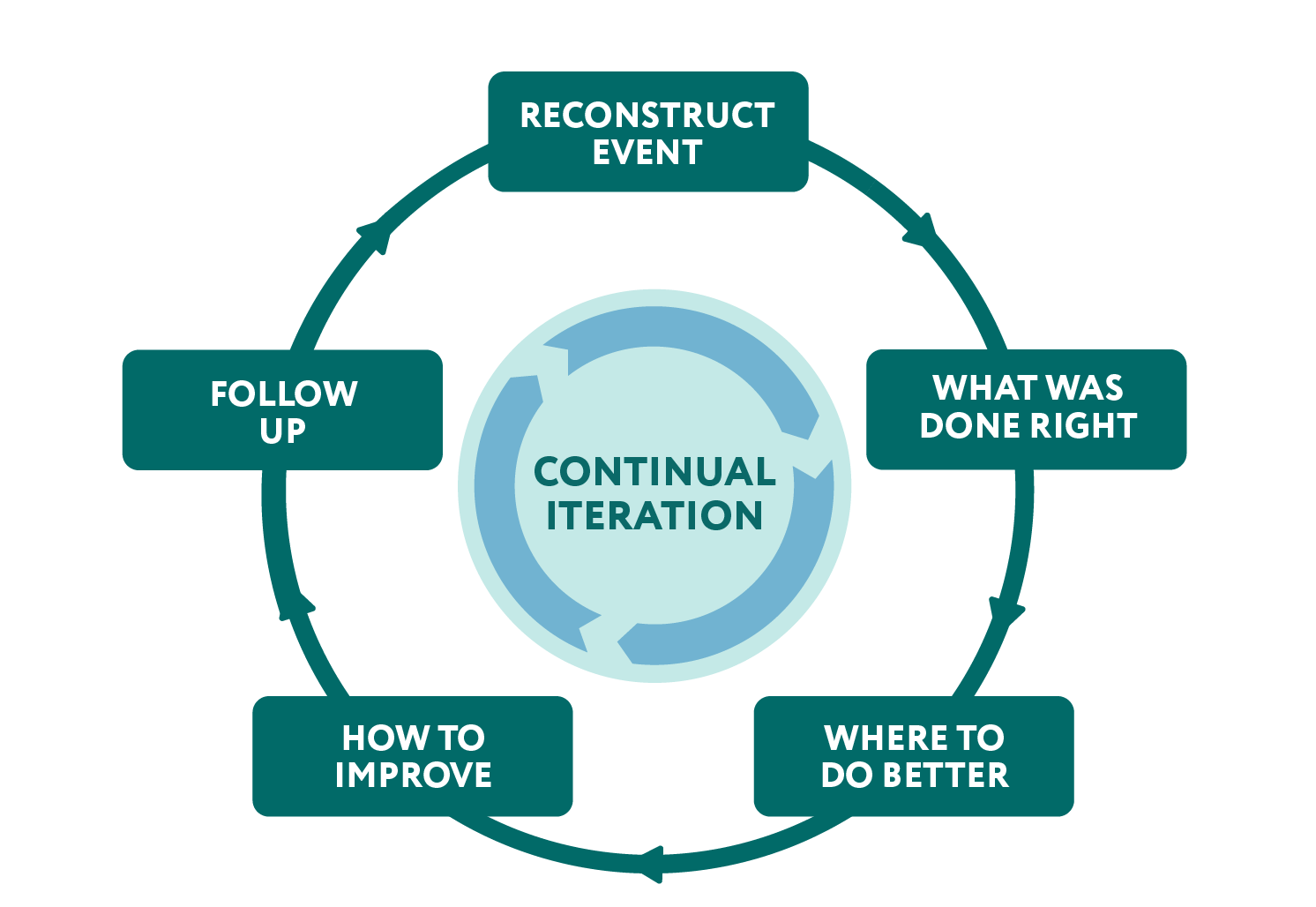

One way to create a co-learning feedback loop is to conduct co-learning debriefings (Figure 4).

For the co-learning debriefing session to be productive:

- The right processes need to be put in place, such as feedback channels for participants to provide their suggestions.

- Participants of the debriefing session should have the right attitude: one of learning and not of placing blame on others.

- The debriefing process should result in actionable and tangible improvements for performance tracking.

During debriefing sessions, there are three types of questions to surface:

- What was done right—participants think about the positives and acknowledge efforts put in by themselves and others towards the intended goals. This is an important step as debriefing sessions could otherwise easily descend into blame-games and derail morale.

- Areas for improvement—participants analyse past activities or events to determine the root causes of any issues presented.

- How to improve—participants brainstorm and develop solutions together and ensure that the lessons learnt will contribute towards subsequent iterations of the programme.

ROLES IN CO-CREATION AND CO-DELIVERY

For co-creation and co-delivery to be possible, the people, public and private sectors cannot work in silos. But what are their most appropriate respective roles? While different projects will have different parameters and arrangements, I suggest that these key roles may be usefully distinguished thus: the people sector serves as the executor, the public sector as the enabler, and the private sector as the sponsor.

| PEOPLE SECTOR AS EXECUTOR |

|---|

| People sector organisations, such as social service agencies (SSAs) and charities, enhance social good through their initiatives and programmes. These activities generate social impact, improving quality of life for the community. Co-creation and co-delivery enable the people sector to produce better initiatives with greater relevance and reach, with greater social impact for the community. Working with the private and public sectors greatly enhances the resources and scale available for their work. Engaging with the beneficiaries they serve help people sector organisations more fully understand actual needs, wants, and concerns, particular for the crucial last mile of services, and to better appreciate and address the root causes of problems. |

| PUBLIC SECTOR AS ENABLER |

|---|

| Public sector organisations, such as government agencies and statutory boards, are no longer the primary executors of social services. Instead, they serve as catalysts, helping to facilitate the development of new social initiatives by providing knowledge, infrastructure development, grants, training, and policies to guide and support people sector organisations in implementing social interventions. For instance, if a youth-focused SSA wants to venture into eldercare due to rising demands from their beneficiaries, government agencies can support this by educating the SSA on the current eldercare landscape, key government policies on active ageing, and potential partnerships to expedite development. |

| PRIVATE SECTOR AS SPONSOR |

|---|

| Private sector organisations, from large corporations to small and medium-sized enterprises, often undertake initiatives that contribute to enhancing social good, as part of their corporate social responsibility agenda. Businesses may engage in philanthropic projects that help fund non-profits, or they may lend effort and expertise through corporate volunteers with skills in areas like project management or IT. The private sector may also be able to offer or share corporate resources such as computer systems or physical office space with non-profit organisations lacking access to these resources. |

MOVING FORWARD WITH CO-CREATION AND CO-DELIVERY

In pursuing co-creation or co-delivery, we need to be mindful that different individuals among the many stakeholders in the community will have different levels of commitment. Not everyone wishes to be fully involved in a project. Many are satisfied with being kept informed about new developments—but this does not mean they are indifferent to project outcomes. We should incorporate ways to keep this silent majority updated on the status of initiatives intended to meet their needs.

In the long term, we must also be sure to take measure of the actual social impact of co-creation and co-delivery projects.2 This might include evaluations of whether community empowerment has improved: through surveys or other studies of whether members of the community feel more agency and self-efficacy. Such measures help demonstrate the effectiveness of co-creation and co-delivery to all stakeholders—generating a virtuous cycle of engagement and success—and foster accountability and transparency.

As our world continues to become more volatile, uncertain and complex, collaborative approaches to addressing societal issues will become ever more necessary. More work still needs to be done to develop a more nuanced and effective co-creation and co-delivery methodology for Singapore's context: particularly ways to enhance co-visioning, co-action, and co-learning. I invite all interested parties to collaborate with us in this endeavour!

NOTES

- L. Wong, C. S. Chan, G. Fu, et al., and the Forward Singapore Workgroup, Building Our Shared Future (Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth, 2023), https://www.forwardsingapore.gov.sg/-/media/forwardsg/pagecontent/fsg-reports/full-reports/mci-fsg-final-report_fa_rgb_web_20-oct-2023.pdf.

- For more information about implementing social impact measurements, see: H. S. Ang, Restructuring Charities (Part 2): Toolkits and Best Practices (Institute of Singapore Chartered Accountants, 2023), https://ca-lab.isca.org.sg/insights/restructuring-charities-part-2/.