Horsemen and Super-Powers: Learning to Design in Government

ETHOS Issue 23, October 2021

DESIGN’S TRANSFORMATIONAL SUPER-POWER

The Singapore Public Service has had a longstanding reputation of efficiency and customer service. We have been at the forefront of e-government services, referenced heavily from private sector management frameworks and principles, and have undergone decades of process improvement methods such as Six Sigma and Kaizen.

By the time I was tasked to develop public sector innovation and service approaches in the Prime Minister’s Office in 2009, there were very little efficiency gains left to be squeezed out of the system.

We were also experiencing the tensions and limitations of frameworks and principles adopted from the private sector around customer service. The fact is that, as government, we don’t choose our customers. The act of governing is about seeking the best compromise: you cannot make everyone happy.

The ‘aha’ moment came when I visited a Ministry’s new service centre, co-designed with IDEO. While others on the same tour probably saw a very lovely space, I saw something completely different: I saw transformed civil servants.

These were former colleagues, with whom I had once written rules which were sometimes kept deliberately opaque to prevent people from ‘gaming the system’. Implementation of these rules required convoluted processes. And as ‘typical civil servants’, we had been afraid of getting ‘feedback’ from the public, because they invariably were complaints.

Except now during that particular visit, these same ex-colleagues were saying things like: “we want to be transparent about our processes”, and “we want people to feel guided in meeting their goals”, and “we need to trust our customers if we want them to trust us”, or “we need to talk to the public to understand their experience from their eyes”. I asked myself: what happened to them?

Design happened to them.

They learnt to listen to people's stories and search for meaning behind those experiences. They came to view their customers as partners in achieving the same goals, not as adversaries. Most of all, they learnt to let go of fear.

The Power of Design

The sheer breadth of what is considered design and how it affects our lives is mind-boggling—everything from how we use everyday products like a hair dryer, how we access key services like healthcare and education, how we buy things online, how spaces make us feel, and how we express ourselves through what we wear.

Design is simply everywhere.

This Ministry had used the design thinking process to conceptualise the service centre, thinking from people’s needs first and space second. They learnt to listen to people’s stories and search for meaning behind those experiences. They came to view their customers as partners in achieving the same goals, not as adversaries. Most of all, they learnt to let go of fear: the same fear I see holding back so many well-intentioned attempts at change and innovation.

Right then and there, I realised that in order to transform public sector outcomes, we needed to first transform our public officers. Design is not just about the outcomes, although they are important. Design is a mindset; a way of thinking and behaving around problems that puts people first.

I was convinced that we needed to implement design thinking in the public sector. My team and I tried many things: we commissioned a series of experiments using design thinking in four policy areas—to very limited or even no success (more on that later). We wrote a manifesto which was shared with public sector leadership about how to become a citizen-centred public sector. We visited MindLab in Denmark and NESTA in the UK. In 2011, we set up the Singapore public sector’s first in-house design lab, and hired designers into the Public Service. Back then, very few people had heard of design thinking. We had to do a lot of education and awareness-raising.

It felt fantastic, it felt revolutionary. We felt like a small ragtag group of people trying to change the world through design. But we fell short of the impact we had thought we would achieve.

Why?

LESSONS LEARNT: THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF DESIGN DEATH IN GOVERNMENT

The problem is that ‘improved user experience’, the Super-Power of design thinking, is insufficient on its own to overcome many of the wicked and complex problems that governments face.

In business, if you can improve your customers’ experience over your competitor, identify and serve previously unmet needs, or refine existing offers for new markets with new behaviours, the market will reward you. Improving user experience is a strong premise for innovation. This premise further rests on three grounds on which businesses function: one, as long as the new idea has commercial value, you go for it. Two, having proven your business case, you can assemble teams, make new hires, invest in technology and start development. Three, the moment the idea stops making money, you can discontinue it. In other words, design thinking in the private sector depends on an unambiguous goal (profit), a tabula rasa for implementation, and a clear exit strategy.

But governments deal in a very different space. After a decade of observing countless design projects in government, I have discerned a clear pattern for why design thinking does not work the same way for governments as it does for businesses. I call this the Four Horsemen of Design Death: Trade-offs, Disruption, Committees, and Grandfathering (not what you think it means).

</em><div class="break">

</em><p class="break1">

The problem is that ‘improved

user experience’, the Super-Power of design thinking,

is insufficient on its own to

overcome many of the wicked

and complex problems that

governments face.

</p>

</em></div>

First, on goals. Governments deal in the space of multiple and sometimes conflicting policy objectives. Would climate-friendly policies increase business costs and reduce competitiveness? Would stronger social safety networks reduce motivation to work? Is levelling the playing field the right approach towards improving social mobility? A business can hone in on a target market and decide whose experience they want to improve. But for governments who must rightfully serve all, whose experience do you seek to improve, especially if it might mean that one group wins and another loses? The first Horseman of Design Death is Trade-offs, the key reason why our policy experiments using design thinking did not quite pan out. After all, policy is tthe art of navigating trade-offs.

Then let’s look at implementation. Governments operate with legacy systems in policies, technology, HR, finance and procurement. A new idea, or even worse, a disruptive idea, does not carry the same connotation as in the business world. There is nothing cool about disruption in government. You are not disrupting the competition, you are only disrupting yourself, as well as the key essential services that millions of people have come to depend on. You do not want to be known as the government who said, “We are disrupting schools tomorrow!” Stability is prized above all else. Disruption is the second Horseman of Design Death.

Implementation also depends on other stakeholders willing to change how they do things. These could be other departments, other agencies, non-governmental players, or simply the public. The project team does not have direct control of the stakeholders, but can only seek to influence and persuade, usually through Committees: the third Horseman of Design Death. They suck up time and energy, are usually outside the core work of the secretariat, and sprout like mushrooms but are notoriously hard to close down, even long after their reason for being has lapsed.

Finally, let’s look at exit. Businesses can pull products, services or teams out of market. But a government can’t simply shut down an aid programme, an IT system, or an agency overnight because ‘it didn’t quite work out’. I have been involved in closing off government programmes before, and it actually takes longer than setting new ones up. Meet the final Horseman of Design Death: Grandfathering. It means to transition a set of people under old rules and processes while implementing a new system with new rules. The greatest fear of civil servants in implementing a policy change is the nightmare of managing a spaghetti tangle of rules, processes and systems for different sets of people. You’d be surprised at how many seemingly minor exceptions have to be managed through manual processes. Grandfathering means that even as a civil servant is considering a new programme, he is already thinking about how he would have to carry the can long after it fails.

Hence, the clarion call of Design, of the ‘improved user experience’, simply does not carry the same pull in government. And this is not because we don’t care about people’s experiences, but because there are other important things at stake. Valiant teams have tried design thinking but stumbled over the implementation of ideas. One of the key refrains is: “The idea is great, but we just can’t implement it”. At other times, design doesn’t even get its foot through the front door. With all the risks associated with change and unclear benefits, the desire to improve user experience just doesn’t make the priority list.

Implementation depends on other stakeholders willing to change how they do things.

DESIGN ALONE IS NOT ENOUGH

I still believe in the transformational power of design: that it can create impactful outcomes for citizens, and that it can help the Public Service become more responsive and resilient. I’ve also learnt that the Four Horsemen can be overcome—provided certain other conditions are in place.

First, there has to be a really clear, rational and justifiable case for why a government prioritises the needs or experiences of some users, especially if it involves a trade-off against another. The most compelling cases I’ve seen are those that say: improving the experience for this group now will help us hedge against some problematic but undeniable long-term trends. Demographic shifts, climate change, technology breakthroughs, and social attitudes are all examples of forces affecting the government’s operating environment, which are difficult to influence or reverse. Businesses call these market studies; in government we call it futures thinking: the research and study of long-term drivers and forces, critical uncertainties, and potential scenarios.

When I directed the Land Transport Authority’s transformation efforts, the CEO at that time explained that design was critical because Singapore was short on land and we could not continue building roads for cars. Public transport simply could not compete against the sex appeal and status of cars and hence needed to be loveable, not just cheap and accessible. In another example, the Defence Science and Technology Agency1 invested heavily in design innovation capabilities for its engineers because Singapore’s declining citizen population meant that there will be fewer national servicemen in the future, and hence any technology has to be intuitive to use. GovTech’s LifeSG was conceived to address Singapore’s declining population, aiming to support young adults’ coming of age and navigating parenthood.2 When design supports long-term thinking, it has the greatest chance of disarming the Horseman of Trade-Offs. It may even make Grandfathering bearable, and Disruption worth considering.

Second, designers in government must see their job not as designing one single beautiful solution, but a set of solutions across different parts of the system. This inevitably involves compromises to the original design ideas. While each individual solution might not be as sexy or revolutionary as desired, they may together form a coherent set of interventions to tip the system towards a new state. In other words, design thinking meets systems thinking. IDEO.org’s Theory of Change model is very relevant for this.3

A good designer in government is a systems designer. He or she must understand the critical stakeholders in the delivery system, which piece of the puzzle they each hold, their inherent motivations, and what will spur collective action. The job of designer in government is as much about the quality of conversations as the quality of solutions. The key tools of a designer here are reflecting aspirations (why is this important to the collective us?), finding common ground amid different perspectives, searching for exceptions (people who are already managing the problem in new effective ways), and helping stakeholders navigate one another. This holds true whether we are talking about balancing trade-offs or coordinating implementation across agencies.

As challenges get more complex, the alliance-building aspect of a designer will only get more important, and this is not just restricted to government. The recent Emerging Stronger Taskforce Alliances for Action are perfect examples of alliance-building conversations at industry or even cross-sectoral scale.4 The topics covered by the Alliances on the future of robotics, smart commerce, ed-tech, and sustainability (to name a few) were the perfect foil for design, and indeed designers were involved in some of the innovation sprints. However, the designer is not only designing just a solution or service to grow new markets, but also a business case that represents a new form of organising relationships or supply chains. If designers lack the systems mindset, even the most exciting commercial ideas could not be implemented in this alliance context.

</em><div class="break">

</em><p class="break1">

Designers in government must

see their job not as designing

one single beautiful solution,

but a set of solutions across

different parts of the system.

</p>

</em></div>

ADDRESSING COMPLEX CHALLENGES WITH DESIGN

There are many instances where design thinking delivers an important impact to public sector outcomes. I find that design works best when it is applied to a contained moment of interaction between the government and the public. There are many great examples in Singapore of this: the HDB Service Centre at Toa Payoh, Ministry of Manpower’s Employment Pass Service Centre, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, and even the Family Courts have all used design thinking to create a supportive environment for users. The most important outcome from design is relational; we are not just making essential services more efficient, but also providing assurance and improving trust between government and citizens along the way. This trust credit is what gives strength to our social fabric. It allows us as a nation to rally together during tough times like the COVID crisis. This alone makes design extremely important for governments.

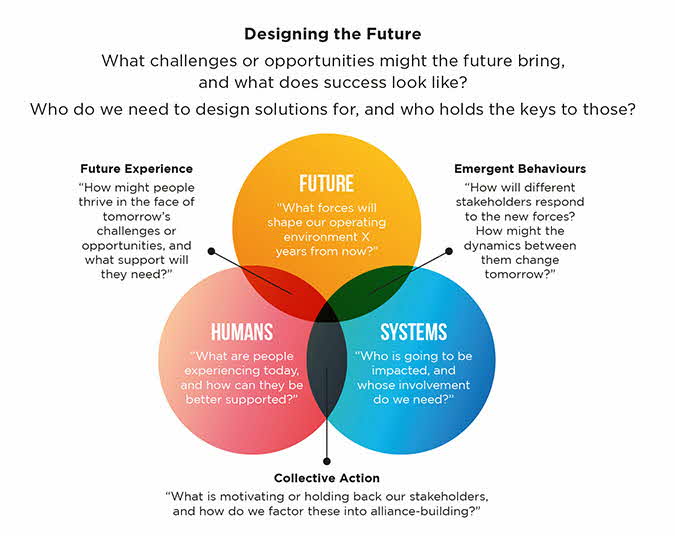

But in order for design to have a true impact on the wicked, complex problems that governments have to solve—climate change, helping small businesses stay competitive, improving social services, preserving arts and heritage, transforming industries, reinvigorating communities— design has to be used in tandem with Futures Thinking and Systems Thinking. While we can pursue each domain as a separate line of enquiry, eventually we have to bring the answers together to gain clarity about the complex problem at hand.

In addition, we should use the tools of design—deep human understanding, storytelling, ideation—to support Futures and Systems. Good conversations are the channels through which we build collective intelligence and drive collective action. This is a fundamentally different dynamic from that of Committees, which tends to be: “I want to achieve this goal so please change what you are doing.” Instead, the Design dynamic is: “What do we understand about this challenge? What are we trying to achieve together?” This is essential for managing complexity.

In short, the key to learning how to design the future involves:

(1) Knowing what questions design can and cannot answer; and

(2) Using tools of design for conversations

Figure 1. Design for Complex Challenges

Balancing Future, Systems and Humans in Tax Collection

TThe Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) is a prime example of hitting the bull’s-eye between Future, Systems and Humans. What initiated IRAS’s digital push for e-filing way back in the 1990s was actually a very central realisation of Humans—that the vast majority of people actually wanted to pay taxes and not run afoul of the tax authority. Hence, IRAS set out to make it as easy as humanly possible to pay taxes. This involved key stakeholders like employers submitting income information back-end to IRAS so that taxpayers did not have to even declare their income statements (Systems). Why? As Singapore is a small country, fiscal discipline will always be an important factor for our survival (Future).

IRAS may not have thought of what they were doing back in the 1990s as design, but it is essentially a very human-centred mindset, coupled with a clear eye on the future and a rigorous systems approach. When civil servants take on complex challenges, whether through approaches called design thinking, digital transformation, or community engagement, they must make sure they are always addressing the whys and hows of Future, Systems and Humans.

EPILOGUE: LEARNING FROM THE FRONT ROW

In my career in the Public Service, I have enjoyed a front row seat to the evolution of design thinking in the Singapore Government for over a decade. Today, I estimate that there might be thirty-plus in-house design capabilities spread across the Singapore Government.

They call themselves different names like Customer Experience or Digital Transformation, but the design thinking mindset is core to their way of working. Some have even hired professional designers. Public Service leaders are also much more exposed to and supportive of design thinking.

In speaking with many of my public sector colleagues, I know they still need support to overcome the Four Horsemen. I suspect that they are going through the same emotional journey as I went through years ago: starting of fully inspired by the power of design, and then becoming deflated bit by bit along the way when the impact did not live up to the potential. We need to help them and others overcome the learning curve of how to use design to its fullest impact in government. Frameworks and tools are just the surface. Design is not something that you do; it is the way that you think and behave.5

My aspiration is to help build design muscle memory for approaching complex problems.

The most important outcome from design is relational; we are not just making essential services more efficient, but also providing assurance and improving trust between government and citizens along the way.

NOTES

- DesignSingapore Council, “A Design Innovation Culture to Elevate Singapore’s Defence Science Game”, January 17, 2020, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.designsingapore.org/stories/a-design-innovation-culture-to-elevate-singapores-defence-science-game.html.

- CNA, “Moments of Life App Rebranded as LifeSG, Providing ‘One-Stop, Personalised Access’ to More than 40 Services”, August 19, 2020, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore.

- Design Kit, “Explore Your Theory of Change”, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.designkit.org/.

- Tham Yuen-C, “Singapore's New Collaborative Approach to Reignite Economic Growth in a Post-Covid-19 World”, The Straits Times, November 20, 2020, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/emerging-stronger-taskforce-outlines-new-collaborative-approach-to-drive-economic.

- DesignSingapore Council, “Three Tips towards Design Being”, February 25, 2019, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.designsingapore.org/stories/three-tips-towards-design-being.html.

</em>