The Role of Public Communications and Engagement in a Pandemic

ETHOS Issue 22, June 2021

“Our COVID-19 response also depended critically on Singaporeans working together and giving the government their trust and support. They understood the need for tough and painful measures, and complied with them. Many Singaporeans’ lives have been severely affected, but they have borne the difficulties calmly and stoically. They had confidence that the government would see them through the crisis and beyond.”

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong 1

Public Trust Matters to Public Policy

Around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has tested the ability of public institutions to respond effectively in a crisis and to keep citizens safe. In a pandemic, how quickly public institutions develop and implement their strategies to contain and isolate the virus has implications on public health.

However, citizen support is just as important in ensuring that public measures work as intended. For instance, for safe distancing measures to be effective, citizens need to be aware of guidelines, accept that they are for their own and others’ protection, and adhere to them even if they are inconvenient. When there is trust in institutions, citizens comply more readily with regulations and there is less need for enforcement.

Ultimately, trust in public institutions has an impact on the efficacy of policies. As senior advisor to the Centre for Strategic Futures and former Head of Civil Service Peter Ho notes: “Particularly in times of crisis… public trust empowers the government to act decisively. Bitter medicine is more easily swallowed when there is public trust.”2

Public trust is dynamic. It is influenced by citizens’ expectations and their perceptions of how the government is doing—both of which can shift over time.3 In an age where people are often bombarded with information from multiple sources, public institutions have to compete for citizens’ mindshare. In volatile, uncertain circumstances, citizens must be able to rely on clear and timely information from trusted sources. Misinformation, or a lack of information, can foster confusion, diminish confidence in public institutions, and discourage desired behaviours.4

Public Communications amid a Crisis

In Singapore, public communications and citizen engagement have been pivotal in engendering public trust amid the pandemic. Through a multi-pronged approach,5 the Government has ensured that citizens are kept abreast of latest developments in COVID-19 cases, and the various safe management practices and measures adopted to limit the spread of COVID-19. Beyond the public communications drive, the Government has also worked hand in hand with citizens to identify and address pressing public needs in the pandemic.

Singapore’s approach is consistent with the World Health Organization's Strategic Communications Framework, which outlines key principles to building public trust in the context of health issues: accessibility, credibility and timeliness.6

Key Principle 1: Information must be accessible

Everyone in society must be able to easily access important health-related information, through traditional media and social media, in ways that they can understand and relate to.

For the COVID-19 pandemic, Singapore’s Ministry of Communications and Information (MCI) has adopted a multi-platform, multi-language and multi-format approach to ensure that vital information reaches different segments of society.7

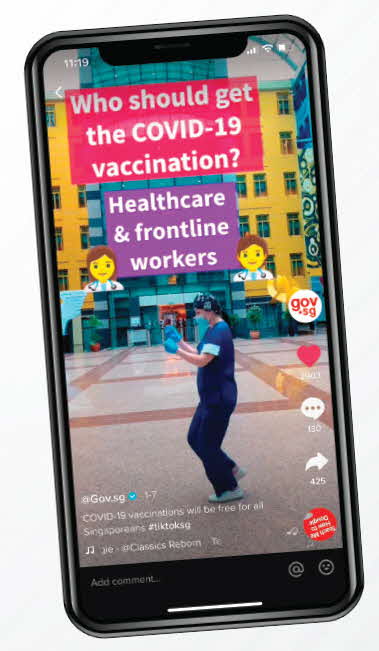

In the digital sphere, updates are pushed out across the official Gov.sg website, as well as official social media and messaging accounts on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp and Telegram, providing the public with accurate, bite-sized updates on the go. Complementing digital platforms are traditional channels such as print media, radio and free-to-air (FTA) TV,8 and physical posters and digital display panels in HDB estates.

Image credit: Gov.sg

|

MCI has also customised communications to engage different audience segments about COVID-19 developments. Messages encouraging good hygiene practices and socially responsible behaviour were aired in English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil. MCI commissioned vernacular programmes, broadcast across FTA TV and radio channels, featuring home-based activities and exercise segments to encourage seniors to keep active and healthy.9 MCI also engaged local content creators and artistes to create short-form content in different languages, combining important health messages with humour. The “Comedians Get Serious” video series featured four well- known local comedians encouraging the public to practice good personal hygiene in a light-hearted and entertaining way.10 A RySense study found 70% of Singaporeans polled agreed that employing humour in public campaigns was good “as these helped keep spirits up during a pandemic”.11 |

Image credit: Gov.sg |

Key Principle 2: Information must be credible

Good public communications are credible and transparent. This means that any information presented must be clear, accurate and backed up by data or science. The messenger is as important as the message. How, when and what information is presented also affects audience perceptions—whether the information is trustworthy and worth complying with.

Misinformation had been a growing concern even before the pandemic struck. However, COVID-19 has underscored how dangerous misinformation can be if left unchecked. According to a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, at least 800 people may have died globally, and over 5,800 people hospitalised, as a result of misinformation that consuming concentrated methanol would cure COVID-19.12 This “infodemic”—the spread of COVID-19-specific misinformation—has become a common challenge around the world, undermining public trust and government efforts to curb the spread of the pandemic.13

One way to tackle this infodemic is to establish the credibility of information sources. Singapore’s Multi-Ministry Taskforce (MTF), set up to manage the pandemic, has worked closely with the Ministry of Health (MOH) and medical experts so that decision- making is informed by the best available medical data.14 The Director of Medical Services at MOH, Associate Professor Kenneth Mak, has been a regular figure at the MTF virtual press conferences, providing inputs and clarifications on health advisories and COVID-19 developments. The MTF has also aligned and updated their advisories based on guidelines from international institutions such as the World Health Organization.15 Communications based on technical expertise lends credibility to the information provided.

Public trust, communications and engagement operate in a virtuous cycle, where one feeds into and builds upon the other.

Establishing credibility is challenging in a “post-truth” world. For public institutions, the pervasiveness of social media and online messaging platforms can be both a boon and bane. While they can be used to push out information quickly to a wide audience domestically and globally, these same channels allow for misinformation to propagate just as rapidly.

To combat this, the Government has tapped on social media and popular messaging platforms such as Telegram and WhatsApp to dispel false claims. Citizens can access verified information on their preferred communication channels, which can help counter the false information they might receive there.16 But this approach is predicated on the underlying trust citizens have in public institutions. Public trust, communications and engagement operate in a virtuous cycle, where one feeds into and builds upon the other.

With countries now rolling out vaccination programmes, misinformation and scepticism over the effects and efficacy of the new COVID-19 vaccines have also been on the rise. According to survey findings in late-2020 by the Nanyang Technological University, close to 25% of individuals polled in Singapore believed that COVID-19 vaccines altered DNA, which is untrue.17

Misinformation could lead to greater vaccine hesitation. If governments do not understand ground concerns and do not swiftly educate the public on the true mechanisms, benefits and risks of the new vaccines, public trust could wane and affect vaccine take- up. Extra efforts may have to be taken to address these misconceptions. In Singapore, volunteers from the People’s Association and Silver Generation Ambassadors are conducting house visits to specifically address the concerns of seniors, who may be more vulnerable to misinformation.18

Governments may also take legislative action against misinformation, as part of a broader spectrum of responses. The Singapore Government has used the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) to correct falsehoods circulated during the pandemic. The challenge for governments is to strike a balance between deterring misinformation and not being perceived as unduly harsh.

However, vaccine hesitation is a complex issue, for which misinformation is only one factor. The decision to take up the vaccine can be influenced by other considerations, such as individual experiences and personal risk assessments. Singapore’s ability to contain COVID-19 has ironically led some to wait to take up the vaccine, because of the perceived low risk of community exposure and low fatality rate in the city-state.19 Public communication and education efforts must take into account such nuances when considering how to foster public trust in vaccines and other health measures.

Consistency can be a challenge, especially in a pandemic when the situation is constantly evolving. Changes have to be communicated clearly, in a manner that builds trust.

To Mask or not to Mask?

Early in the pandemic, when there was no official evidence that wearing masks could prevent the spread of COVID-19, the Singapore Government stipulated that masks were to be worn only when ill. In early April 2020, alongside the implementation of a nation-wide Circuit Breaker, the Government updated its advisory on mask-wearing. People were no longer discouraged from wearing masks even if they were well.1 There was some public backlash as the Government was perceived to be inconsistent.

The Multi-Ministry Taskforce stepped in to explain the rationale for updating the mask-wearing advisory through a virtual press conference.2 It explained that the decision was guided by new scientific evidence that asymptomatic patients could transmit COVID-19, and concerns about undetected community cases at the time.3 By mid-April 2020, the Government made it mandatory to wear masks in public spaces.4

The incident illustrated the importance of credible information, clear explanation of changes, and updated messaging in fostering public trust.

NOTES

- Gov.sg, “PM Lee: The COVID-19 Situation in Singapore (3 Apr)”, April 3, 2020, accessed February 5, 2021.

- “Why Has Singapore Changed Its Advice on Wearing Masks amid the COVID-19 Outbreak?” CAN, April 3, 2020, accessed February 5, 2021.

- “COVID-19: Why Singapore Changed Its Guidance on Masks and Made It Mandatory”, CNA, April 14, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWxfZjH2kf8&ab_channel=CNA.

- Ang Hwee Min and Rachel Phua, “COVID-19: Compulsory to Wear Mask when Leaving the House, says Lawrence Wong”, CAN, April 14, 2020, accessed February 5, 2021.

Key Principle 3: Information must be timely and relevant

Critical information should be disseminated in a timely a n d relevant way. If information is delayed and citizens are made aware of developments through other sources, authorities may be seen to be withholding information.20 The absence of updated news could also lead to speculation and unnecessary fear. Messages should also be framed in a way that is relevant to the target audience. This means governments should have an ear to the ground in framing messages that elicit the desired actions.

In a time of great uncertainty, routine updates and timely information can give reassurance to the public. Since the outbreak of the pandemic in Singapore, daily case updates and press conferences held by the MTF have become the “new norm” for information on COVID-19. Information from these daily updates are swiftly disseminated through multiple channels. Since citizens may face a deluge of information about the pandemic, updates pushed out through social media and messaging platforms are kept short and easily understood. The daily case updates follow a familiar template and timing. Summarised safe management “Dos and Don’ts” provide bite-sized, actionable items that the audience can follow up on.

The importance of transparent and relevant information was underlined by the controversy surrounding Singapore’s TraceTogether (TT) programme,21 which facilitates the speedy contact tracing deemed vital to managing the pandemic’s spread. While the public was originally told that TT data would only be used for contact tracing purposes,22 it was subsequently revealed in Parliament that the police could access TT data for criminal investigations under the Criminal Procedure Code.

This belated announcement resurfaced concerns over data privacy and public trust, with real consequences: some 350 users opted to have their TT data deleted in January 2021.23,24

Effective communications must strike the right balance in tone, both in terms of its content as well as how it is conveyed.

Striking the Right Tone

In Singapore, the Virus Vanguard webcomic campaign, launched on Gov.sg in mid-April, was intended to be a light-hearted way to spread awareness of safe management measures. But netizens took issue with the comic’s characters and their backstories, and cited similarities to characters by other artists. The comic was also considered ill-timed as daily case numbers were high at the time of the launch. Although well-intentioned, the poor reception highlighted how public communications need to be particularly sensitive, especially in fraught times.

Beyond Information to Inspiration

In a crisis, public communications must go beyond conveying information. On the right occasion, they can also offer encouragement, lift the national spirit and inspire hope.

In 2020, MCI launched a series of initiatives via broadcast media and multiple online platforms to achieve this. For example, two media campaigns were timed specifically for the unprecedented Circuit Breaker, which kept many at home, to encourage and unite people despite their physical separation.

A national singalong event was also held at 7:55 p.m. on 25 April 2020,25 a few days after the extension of the Circuit Breaker was announced. At the same moment island-wide, Singaporeans across the nation sang the popular national song “Home” from their windows and balconies, waving lights as a show of solidarity and support for frontline and migrant workers. A compilation video, taken from over 5,000 video submissions, was broadcast later that same evening.

A 15-minute segment, paying tribute to frontline workers and featuring individuals impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, was also launched on national TV on 1 June 2020, when the Circuit Breaker ended. These campaigns helped boost morale amid a trying period of the crisis.

Galvanising the Public to Tackle the Pandemic

Effective public communications are only one aspect of cultivating public trust. The burden of tackling the pandemic is not limited to governments or healthcare workers and requires broader community involvement.26

Indeed, the outpouring of help in Singapore since the outbreak shows that the public is willing and able to support those adversely impacted by the pandemic. For example, several community initiatives were kickstarted to translate medical information for healthcare and migrant workers so they could communicate better with each other.27

Many of the pressing challenges of dealing with COVID-19 have also been addressed by engaging citizens in co- creating and co-delivering solutions. This approach allows a government to tap on the collective wisdom and insight of different groups to deliver help where it is most needed.28 In the process, a government and its public build up mutual trust by cooperating on initiatives for the common good.

Citizen engagement offers a platform and voice to citizens to contribute to public decision-making and implementation. Depending on the mode of engagement, the level of citizen participation may differ, with co-delivery and co-creation entailing deeper engagement and involvement by citizens.

A government and its public build up mutual trust by cooperating on initiatives for the common good.

During a pandemic, how governments engage citizens may take a different form, but the underlying principles remain unchanged. Expectations should be articulated clearly and early to avoid misconceptions. Engagement that is perceived to be merely a “paper exercise” risks undermining public trust and confidence. This is especially salient in an environment where access to information is vast and easy, citizens are more discerning, and expectations of the government are high.29 Good citizen engagement is intentional, people-centric, collaborative, transparent and inclusive.30

This is similar to what some Public Health researchers from the Dialogue, Evidence, Participation and Translation for Health (DEPTH) research group at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine have outlined in their four steps31 for developing effective citizen participation in response to COVID-19:

1. Invest in co-production

The DEPTH research group recommends that governments dedicate specific space, resources and manpower to coordinate community participation.32 Providing space (whether virtual or physical) and information on relevant networks, agencies and available funding sends the signal that governments are willing to support ground-up initiatives in a concrete way.

For example, SGUnited, a Singapore Together initiative, is a rallying movement for Singaporeans to work together to combat the challenges of the pandemic. The SGUnited banner has brought together community initiatives supporting frontline workers, as well as vulnerable groups affected by COVID-19.

In response to community support and interest in volunteering, the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth and the National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre created the SGUnited Portal.33 This one-stop site connects interested volunteers with charities that need vital manpower and offers people the autonomy to kickstart initiatives that address important issues in the community.

One such initiative is Welcome In My Backyard, a campaign led by a group of volunteers seeking to encourage Singaporeans to be more accepting of migrant workers, after it was announced that healthy workers would be relocated to housing estates to stave off the spread of COVID-19. Comprising local ambassadors who live in estates that would house the workers, the volunteers seek to debunk stereotypes of the workers.34

2. Work with community groups

Community groups can play a pivotal role in citizen engagement. Their on-the-ground expertise and networks provide insight into the immediate needs and challenges of those affected by the pandemic. They are well-placed to raise awareness and mobilise the community in ways governments may not be able to do as quickly in a pandemic.

The SGUnited Buka Puasa initiative is a multi-partner collaboration between the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS), local mosques, the Rahmatan Lil Alamin Foundation, the People’s Association, Roses of Peace and the Singapore Malay Chamber of Commerce and Industry.35 The project aimed to deliver 20,000 meals a day during Ramadan to frontline healthcare workers and their families, zakat beneficiaries of MUIS, and other families who needed the meals. By early May 2020, the project had managed to raise close to S$2.6 million in funds, including through community donations.36 These joint collaborations not only bolster public trust, but also strengthen mutual trust within the community.

3. Commit to diversity

Citizen engagement can be an important channel for different experiences to be shared with policymakers and to co-create solutions, provided engagement modes are accessible to and intentionally inclusive of different segments of society.37 The effects of the pandemic are not felt equally across different segments of society. Low-income individuals are disproportionately affected by the economic downturn. People with disabilities may face difficulties with certain safe management measures that others may not.

Public trust may be affected when policies or issues have disparate effects for different people. First, groups who find it difficult to access such engagement channels may feel excluded and ignored, and cynicism over citizen engagement efforts could grow. Second, if those consulted or engaged are largely homogenous groups, there is a risk of missing unintended consequences. This could affect the perceived ability of governments to deliver effectively—which is a function of public trust.

In Singapore, the Emerging Stronger Conversations (ESC), initiated in June 2020, has brought together citizens in virtual Zoom sessions to reflect on the impact of the pandemic, raise issues and propose ideas. The Government has committed to developing partnerships through the Singapore Together Alliances for Action to tackle prominent themes raised, translating the conversations into concrete actions.38 To ensure greater accessibility, ESC sessions have been held in Mandarin, Malay and Tamil, in addition to English.39 As part of the ESC, some 120 members in the disability community also gathered to share with political office holders their experience during COVID-19.40

4. Be responsive and transparent

Being responsive and transparent is not only important during citizen engagement, but after as well. Leaving citizens high and dry after engagement activities are over can be detrimental to public trust: engagement can seem merely transactional or superficial.

Policymakers involved in citizen engagement highlight the importance of “closing the loop”: one way this can be done is to summarise the insights gleaned and explain the next steps that will be taken.41 In the case of the ESC, sessions were summarised into an ongoing series of infographics, highlighting the key themes and talking points raised.42 Subsequently, a report was published online, on a website which also provides multiple opportunities for further participation and action by citizens.

There is often a time lag between engagement and the tangible implementation of solutions. In the interim, it is important to keep the process open and transparent, ensuring that citizen participants are made aware that their contributions have been heard; they may also want to know how their feedback may feed into a specific policy. As not all ideas may be incorporated, governments should manage expectations by explaining the rationale behind their decisions. Doing so provides assurance to citizens that their participation is valued and valuable.

Building Trust in Government after the Pandemic

Trust and engagement enjoy an interdependent relationship.43 Citizen engagement is a useful means to understanding the needs of citizens and fostering confidence in government. Conversely, the success of citizen engagement in a crisis also relies on existing public trust built in quieter times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of cultivating relationships and growing community capacity during peacetime. The groundswell of community action was possible due to the strong partnerships and mutual trust between community partners and the public sector, which had been built over a long period of time.

Ensuring that communications and engagement are inclusive, accessible and meaningful goes a long way in maintaining public trust.

Singapore has continued to see high levels of trust in government, evidenced by the findings in the recent Edelman Trust Barometer 2020 report.44 However, it is important that trust-building continues.

Public trust is sensitive to public perceptions and expectations. It hinges on the government’s ability to keep a finger on the pulse of citizen concerns and preferences.

Keeping open and transparent communications is vital. Transparency and trust go hand-in-hand.45 Providing timely, clear and transparent information provides certainty at a time when uncertainty and ambiguity is high. Critically, it also provides assurance and allows for more effective recovery without being sidetracked by wild speculation or misinformation.

Ensuring that communications and engagement are inclusive, accessible and meaningful goes a long way in maintaining public trust. Offering Singaporeans opportunities to contribute, help one another and share personal stories can help our people to feel more rooted and nurture greater national solidarity. Ensuring citizens feel heard and have a sense of ownership in shaping the future can strengthen the government-citizen and citizen-citizen relationships for the long term. Such relationships, founded on hard-earned trust, will be vital as we navigate the uncertainties of the future.

NOTES

- Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, “PM Lee Hsien Loong at the Debate on the Motion of Thanks to the President”, September 2, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Peter Ho, “When Public Trust Is No Longer Centred on the Government”, Today, February 8, 2018, accessed October 19, 2020.

- OECD, Government at a Glance 2013 (OECD, 2013), accessed November 23, 2020.

- Nomi Claire Lazar, “Social Trust in Times of Crisis”, The Straits Times, April 3, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Ministry of Communications and Information, “Gov.sg Launches New Channels to Keep the Public Informed about COVID-19”, press release, April 2, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- World Health Organization, WHO Strategic Communications Framework for Effective Communications (World Health Organization, 2017), accessed October 19, 2020.

- See Note 5.

- Ibid.

- Ministry of Communications and Information, “Annex A: Details on MCIs Programming Efforts COVID19”, press release, April 2, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Ibid.

- RySense, “Impact of COVID-19 (Part 2): Perceptions of Digital Campaigns on COVID-19”, 2020.

- Md Saiful Islam et al., “COVID-19–Related Infodemic and Its Impact on Public Health: A Global Social Media Analysis”, The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103, no. 4 (October 2020): 1621–1629.

- OECD, “Transparency, Communication and Trust: The Role of Public Communication in Responding to the Wave of Disinformation about the New Coronavirus”, July 3, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Karamjit Kaur, “Coronavirus: MOH Works Closely with Medical Professionals to Guide Task Force”, The Straits Times, July 6, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Lester Wong, “Legal Cut-off Age for Kids in Singapore to Wear Masks to Be Raised to 6 and Above”, The Straits Times, September 23, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Dymples Leong, “‘Infodemic’: More than a Public Health Crisis”, RSIS Commentary, no. 123 (June 2020): 4.

- Ang Qing, “Around 1 in 4 Singapore residents surveyed believe false claim that COVID-19 vaccine alters DNA”, The Straits Times, December 24, 2020, accessed February 5, 2021.

- Ministry of Communications and Information, “MCI’s Response to PQ on POFMA Office’s Actions in Regard to Misinformation about COVID-19 and COVID-19 Vaccination”, Parliament QAs, February 2, 2021, accessed February 5, 2021.

- Chen Lin and Aradhana Aravindan, “COVID-19 Vaccine Stirs Rare Hesitation in Nearly Virus-Free Singapore”, Reuters, December 23, 2020, accessed February 5, 2021.

- Gareth Tan, “TraceTogether Presents Chance for Singapore to Restore Track Record on Data Privacy and Security”, Today, May 22, 2020, accessed February 5, 2021.

- Smart Nation and Digital Government Office, “Parliamentary Sitting on 5 June 2020”, June 5, 2020, accessed February 5, 2021.

- Kenny Chee, “Bill Limiting Police Use of TraceTogether Data to Serious Crimes Passed”, The Straits Times, February 2, 2021, accessed February 5, 2021.

- “350 People Asked for Removal of their TraceTogether Data in Past Month, while 390,000 Came Onboard: Balakrishnan”, Today, February 3, 2021, accessed February 5, 2021.

- Jean Lau, “Sing Along to Home on Saturday to Thank Front-Line, Migrant Workers”, The Straits Times, April 28, 2020, accessed April 20, 2021.

- Lim Min Zhang, “World News Day: COVID-19 Pandemic Underscores Need for Good Public Communication and Credible Media, Says Panel”, The Straits Times, September 28, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Yong Jun Yuan, “Heroes Unmasked: Translation Initiatives Pop Up to Bridge Communication Gap for Migrant Workers during COVID-19”, Today, May 15, 2020, accessed April 22, 2021.

- Cicely Marston, Alicia Renedo, and Sam Miles, “Community Participation Is Crucial in a Pandemic”, Lancet 395, no. 10238 (2020): 1676–1678.

- Paul C. Light, “The Nature of Public Trust in Government: Interview with Paul C. Light”, Ethos, June 14, 2016, accessed November 20, 2020.

- The SG Together Pullout Guide to Citizen Engagement articulates five core principles for effective citizen engagement: Be Intentional, Be People-Centric, Be Collaborative, Be Transparent, Be Inclusive. See Challenge, “The SG Together Pullout Guide to Citizen Engagement”, January 23, 2020.

- See Note 28.

- Ibid.

- Matthew Loh, “Want to Help with the COVID-19 Response? Portal Launched for S’poreans Keen to Donate, Volunteer”, Today, February 20, 2020, accessed November 20, 2020.

- Yuen Sin, “Campaign to Make Workers Feel Welcome in Housing Estates”, The Straits Times, April 20, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- Linette Lai, “15,000 Meals To Be Delivered Daily to Healthcare Workers and Needy Families during Ramadan”, The Straits Times, April 18, 2020, accessed November 20, 2020.

- Shivraj Rajendran, “Mosques Here Raise $600,000 to Provide Meals to the Community during Ramadan”, The Straits Times, May 8, 2020, accessed November 20, 2020.

- See Note 28.

- Gov.sg, “DPM Heng Swee Keat: Emerging Stronger Together”, June 20, 2020, accessed November 20, 2020. The name was subsequently changed from Singapore Together Action Networks to Alliances for Action.

- Fabian Koh, “Emerging Stronger Conversations: First Mandarin Session Held; Tamil, Malay Ones Will Follow”, The Straits Times, October 24, 2020, accessed November 20, 2020.

- Goh Yan Han, “120 from Disability Community Discuss Future beyond COVID-19”, The Straits Times, November 12, 2020, accessed November 20, 2020.

- “The SG Together Pullout Guide To Citizen Engagement”, Challenge, January 23, 2020, accessed November 20, 2020, https://www.psd.gov.sg/challenge/ideas/deep-dive/singapore-together-pullout-guide-to-citizen-engagement.

- Saki Kumagai and Federica Iorio, Building Trust in Government through Citizen Engagement (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020), accessed November 20, 2020.

- Shefali Rekhi, “Trust in Singapore Government up: Edelman Poll”, The Straits Times, June 22, 2020, accessed October 19, 2020.

- See Note 43.