Strengthening Mental Wellbeing in a Pandemic

ETHOS Issue 22, June 2021

A Pandemic of Stressors

Clinical criteria such as suicide rates, depression and anxiety diagnoses, and institutionalisation rates are commonly used to evaluate mental health. But this is only one aspect of mental wellbeing, which relates to a person’s overall ability to positively experience life, effectively manage life’s challenges, realise their potential and make a meaningful contribution within their community.1

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to many shocks that have distressed Singaporeans’ mental wellbeing. These range from anxiety over the highly transmittable and potentially deadly virus itself to the prospect of economic decline and unemployment, a potential shortage of essential goods, and restrictions on movement and social contact both within and across national borders. In Singapore, such stressors have led to behaviours such as panic buying at supermarkets, a rise in calls to suicide prevention and crisis hotlines, and domestic abuse cases.

Existing inequalities can compound declining levels of wellbeing.

The 24/7 National Care Hotline, set up shortly after Singapore went into its Circuit Breaker lockdown in April 2020, received close to 28,000 calls within five months of its establishment. The Samaritans of Singapore similarly noted a 30% increase in calls to its suicide prevention hotline during the Circuit Breaker.2 April 2020, specifically, saw a 42% increase in helpline calls, with callers sharing concerns around financial hardship, stress around the home environment, and anxiety from being separated from loved ones.

Globally, the pandemic has seen an increase in violence against women, with a rise in complaints of violence or calls to report domestic abuse. Singapore saw a 33% increase in such reports, according to an AWARE Women’s Helpline report.3 According to the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF), the number of enquiries for its adult and child protection services was up by 14% in the first two weeks of the Circuit Breaker period.4

Existing inequalities can compound declining levels of wellbeing. For example, during the Circuit Breaker, when periods of working or schooling from home were enforced, those from low-income households were less likely to have access to the equipment, workspace or privacy needed to carry these tasks out effectively.5 The Ministry of Education did provide laptops to support students from low-income households in home-based learning. However, finding a conducive environment for learning remained a challenge, with some resorting to working in the common corridor or stairwell of their housing estates. Such issues can affect individual wellbeing or even cause friction among family members and neighbours.

While prolonged national lockdowns and social separation measures reduce the risk of viral transmission, they can also lead to increased anxiety, depression, and stress.6, 7 In April 2021, a Straits Times survey, conducted one year after the Circuit Breaker, found that people are socialising less, their social circles have shrunk and their overall mental wellbeing has taken a hit.8

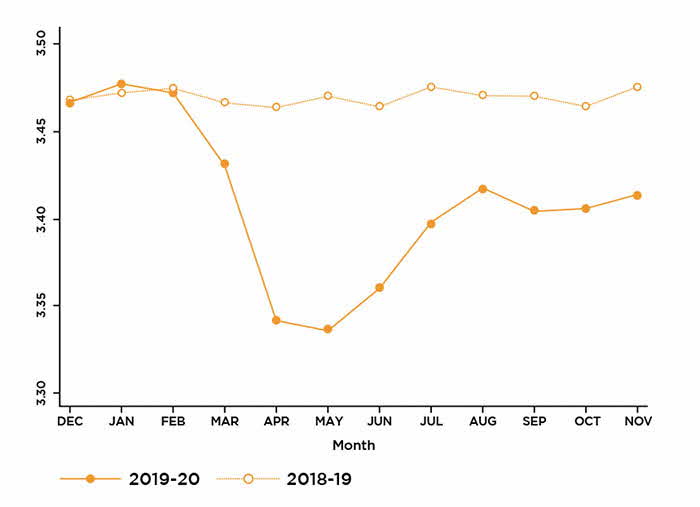

Figure 1. Elder Singaporeans' Life Satisfaction over Time

Source: T. Cheng, S. Kim, and K. Koh

Furthermore, a study by Cheng, Kim and Koh noted a significant drop in life satisfaction during the lockdown period among older Singaporeans (see Figure 1).9 Cheng, Kim and Koh also found that individuals who reported a drop in household income experienced a decline in overall life satisfaction, almost twice as large as those who did not report any such loss. This suggests that the economic impact of the pandemic is a key contributor to the decline in self-reported wellbeing of middle-aged and older Singaporeans. However, others who did not experience an income loss also reported lower life satisfaction. This suggests that anxiety and stress associated with a curtailment of movement and the disruption to daily activities have also played a role. While the findings from this study may not be completely generalisable, they offer a timely and important evaluation of older Singaporeans’ wellbeing during the pandemic.

While prolonged national lockdowns and social separation measures reduce the risk of viral transmission, they can also lead to increased anxiety, depression, and stress.

Framing Mental Wellbeing: Five Priorities

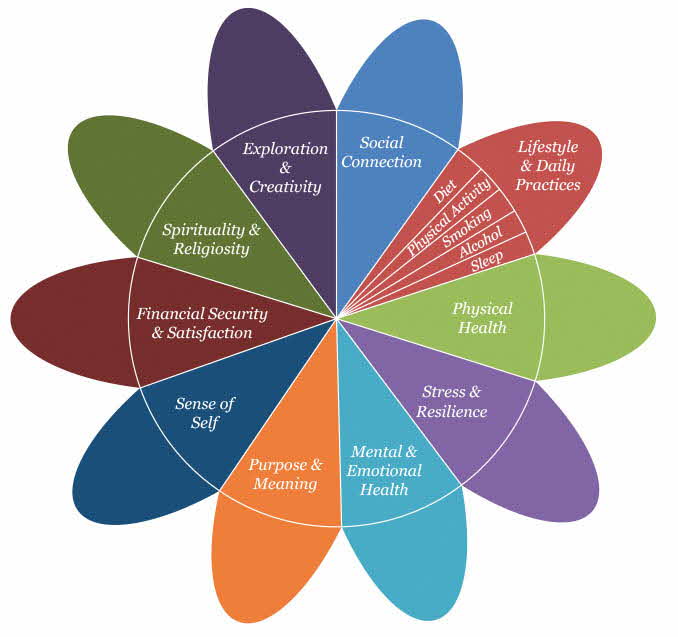

The Stanford WELL for Life Study (WELL) is an international longitudinal study which defines and assesses multiple dimensions of wellbeing beyond medical and healthcare fields, including financial, spiritual, emotional and social connectedness, among others. 10

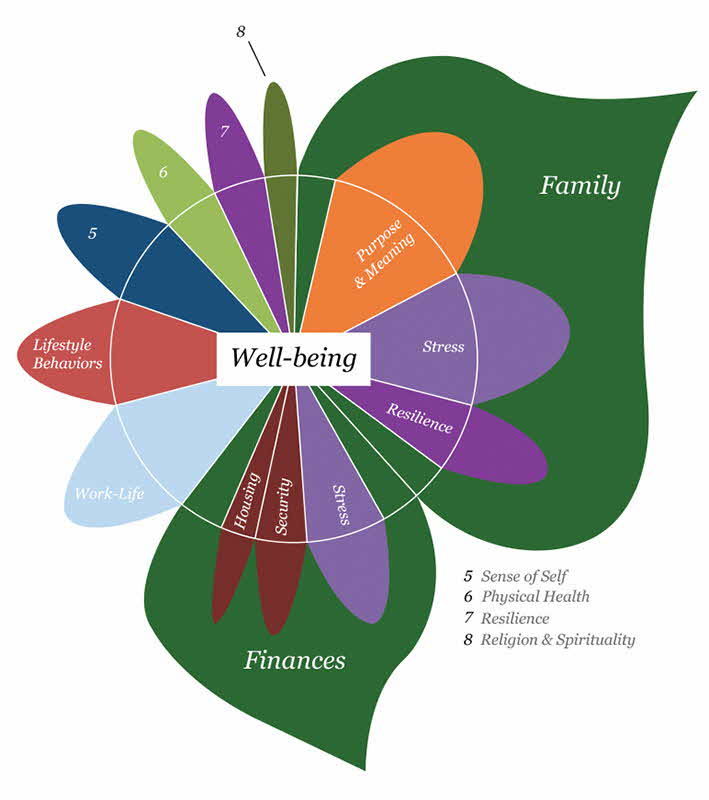

As part of the study, WELL researchers have developed a tool to frame and quantify mental wellbeing. For the 10 dimensions in the WELL Flower (see Figure 2), various study sites have also identified the “weight” of the flower petals based on their contribution to wellbeing as determined by study participants. In the US study site, social connectedness emerged as the most weighted domain of wellbeing, followed by lifestyle behaviours and physical health. The WELL study in Taiwan, a society that mirrors Singapore more closely, found family, finances, sense of self, lifestyle behaviours and work-life to be the top five priorities for improving mental wellbeing (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Stanford WELL Flower, dimensions unweighted11

Source: Stanford WELL for Life

Figure 3. Stanford WELL Flower Taiwan, dimensions weighted12

Source: Stanford WELL for Life

These five priorities offer a useful frame with which to examine the challenges of maintaining mental wellbeing in Singapore during the COVID-19 outbreak, and to consider how the pandemic response measures have made a difference.

Mental Wellbeing: Interventions that Helped

Supporting Families

The family is the first line of support for most Singaporeans. As such, many assistance measures in Singapore are designed around families: in supporting families, individuals too are uplifted. Conversely, if households become less able to care for their members (because of financial or other resource constraints), individuals suffer. This is especially the case for those in vulnerable groups, such as lower-income residents, the elderly, or those living alone.

Recognising that the pandemic would tax Singaporean households, the MSF decided in April 2020 that social service offices (SSOs), senior care centres, residential and home-based care services, and community mental health services would continue to support their clients throughout the Circuit Breaker period, while introducing strict safety measures.13 Those under Stay-Home Notice (SHN) or quarantine were provided for in terms of food and financial assistance. The Silver Generation Office also reached out to vulnerable seniors residing alone or in frail condition, while its ambassadors made the rounds to visit seniors to inform them of good hygiene practices and ensure their needs were met.

When working and schooling from home were enforced during the Circuit Breaker period, 14, 15 almost all Singaporeans experienced a strain on their shared home spaces. A government advisory highlighted the anxieties felt by employees who were asked to work from home for the foreseeable future.16 The advisory asked employers to offer flexible work arrangements, to allow families to make alternative daily care arrangements for younger or older dependents, and balance sharing workspaces and devices among family members.

During the outbreak, businesses did step up to support family wellbeing.17 Firms such as OCBC Bank implemented PSLE leave for parents, while businesses like M. Tech loaned out devices to parents with children who lacked devices to undertake home-based learning. For struggling families, CapitaLand, under its philanthropic arm the CapitaLand Hope Foundation, launched a #MealOnMe initiative in partnership with the Food Bank.18 Great Eastern promoted and matched donations towards students and their families who had suffered income losses due to COVID-19. It also helped provide meals and access to medication for children and seniors, and accommodation and essential assistance for homeless and displaced individuals and their families.

When working and schooling from home were enforced during the Circuit Breaker period, almost all Singaporeans experienced a strain on their shared home spaces.

Community groups, such as Community Development Councils and Self-Help Groups, also extended support to individuals and families during the pandemic.19 Grants were set up to scale up local assistance schemes to vulnerable households.20 Community organisations joined to launch an online platform facilitating donations in support of their client groups. For instance, the Mind the Gap campaign had a goal of $50,000 to fund the work of groups such as Daughters of Tomorrow, Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) and ReadAble, to name a few. This community support allowed immediate, direct intervention to needy families; this helped to reduce the stress on familial relations and stave off financial despair.

Community support allowed immediate, direct intervention to needy families; this helped to reduce the stress on familial relations and stave off financial despair.

Easing Finances

Although it started as a healthcare crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic very quickly became a job and livelihood crisis. Across households, real and median incomes declined in the first year of the pandemic.21 These losses would have been greater had the Government not provided transfers and pandemic-support, particularly for smaller households.

To ease financial stress, the Government announced four budgets incorporating a mixture of subsidies, deferment of payments, cash payouts, and special COVID-19 funding for those affected with job- and revenue-loss. Government measures such as the Temporary Relief Fund and the COVID-19 Support Grant (and more recently the COVID-19 Recovery Grant) were designed to benefit different segments of society, including the employed, the unemployed, the vulnerable and low-income, as well as small businesses and digitally-tardy businesses.22, 23 Other initiatives that eased financial strain included the deferment of insurance premiums,24 as well as a new Courage Fund to provide one-time payments to those stricken with COVID-19, whether in or outside the line of duty.

By offering material support in a variety of ways, such measures helped relieve the psychological distress of those whose economic situation had been adversely impacted by the pandemic. They also offered important reassurance that Singaporeans were not being left to fend for themselves in a crisis.

Although it started as a healthcare crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic very quickly became a job and livelihood crisis.

Secure Sense of Self

An individual’s sense of self is how they regard their own nature, ability and worth: it involves their self-confidence and self-satisfaction. Supporting sense of self generally involves building individual capability and resilience.

Recognising that individuals may struggle with low self-esteem or self-satisfaction during the pandemic, a number of helplines were set up to provide support.25 A COVID-19 Mental Wellness Taskforce was also set up to look into the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the population.26 Taking stock of mental health and wellbeing initiatives introduced across ministries and agencies, the taskforce focused on three key areas: first, developing a national mental health and wellbeing strategy to align and guide the work of public agencies; second, setting up a national mental health resources webpage to improve access to relevant information; and third, establishing a national mental health competence training framework to align and standardise training curricula on mental health in the community.27

Attention has also been given to groups that might have been particularly vulnerable to a diminished sense of self. A Youth Mental Wellbeing Network, supported by a number of ministries in partnership with the National Youth Council, was set up specifically to address the needs of Singaporean youth. This initiative considered the findings of the 2016 Singapore Mental Health Survey,28 which identified youth as being susceptible to major depressive disorders, generalised anxiety disorder and other mental wellbeing issues that could be triggered by environmental events—such as the pandemic. In November 2020, another task force, named Project Dawn, provided early detection and appropriate care to at-risk migrant workers—a group that had been significantly impacted by the crisis in a number of ways.29

Supporting Positive Lifestyle Behaviours

According to the WELL study, lifestyle behaviours such as diet, sleep, physical activity and consumption of alcohol and tobacco can all have an impact on a person’s wellbeing. Despite the safe management measures necessitated by the pandemic, there have been some concessions to help residents maintain healthy lifestyle habits. For instance, individuals have been permitted to exercise outdoors throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, and to remove their mask when engaged in vigorous exercise.

Food is an important aspect of the Singaporean way of life, and dining together is a significant social bonding activity. A good meal with friends and loved ones is a morale booster. However, with COVID-19, gatherings for meals have had to be restricted in size; many restaurants and food hawkers have been heavily affected by reduced footfall, with many customers working from home. Nevertheless, there have been efforts to continue to keep Singapore’s beloved food culture going despite the pandemic. One such initiative is the Hawkers United Facebook group,30 which has provided a means for hawkers (even those less digitally savvy) to connect with customers using digital platforms. Such initiatives also help strengthen civic ties and camaraderie—imperative to building up a resilient public health stance in times of crisis.31

As the pandemic progressed, Singapore’s migrant worker dormitories faced extensive quarantine and isolation measures for extended periods.

Taking Care of Migrant Workers' Mental Wellbeing

As the pandemic progressed, Singapore’s migrant worker dormitories faced extensive quarantine and isolation measures for extended periods. Over time, this affected some workers’ mental wellbeing. During the Circuit Breaker period in particular, the COVID-19-hit dormitories saw a spate of suicide attempts.

Working with the Ministry of Manpower and private stakeholders, the inter-agency taskforce sought ways to support foreign workers’ welfare and mental wellbeing. They took the effort to celebrate migrant workers’ holidays, encouraged workers to seek help when needed, and provided help hotlines.1 Non-governmental organisations also offered vital services such as welfare, health care, and crisis management, liaising between employers and financing agents, and advocating for migrant workers’ needs.

Mental healthcare for migrant workers is complicated by linguistic and cultural barriers, along with high levels of stigma in migrant workers’ home countries.2 To offer a listening ear to them, social service organisations Healthserve and Samaritans of Singapore partnered to launch a helpline available in English, Tamil, Chinese and Bengali.3

Note

- P. T. Wong, “Managing Migrant Workers’ Mental Health a ‘Work in Progress’, says MOH Officials after Self-harm Incidents”, Today, August 6, 2020, accessed May 12, 2021,

https://wwww.todayonline.com/singapore/managing-migrant-workers-mental-health-dormitories-work-progress-says-moh-officials-after. - G. W. Lai and B. Kuan, “Mental Health and Holistic Care of Migrant Workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 Pandemic”, J Glob Health 10, no. 2 (December 2020), accessed May 12, 2021, doi:10.7189/jogh.10.020332.

- N. Awang, “Round-the-clock Crisis Hotline for Migrant Workers to Be Set Up by SOS, Healthserve”, Today, March 19, 2020, accessed May 12, 2021,

https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/crisis-hotline-migrant-workers-be-set-sos-healthserve.

Protect Work-Life Balance

Having staff work from home instead of in the office has become an accepted way to reduce contact exposure between co-workers and hence curb the spread of COVID-19. To promote flexible working arrangements during the Circuit Breaker period, the Government provided an enhanced Work-Life Grant to qualifying companies,32 with more than $180 million given to 8,000 companies from April to August 2020, covering almost 90,000 employees.

However, for many Singaporeans, being obliged to work from home has meant a blurring of lines between their professional and private spaces, with some bosses expecting subordinates to be available to work at hours outside usual working hours.33 Singaporeans have also expressed worry about job loss, admitting to working long hours from home to avoid retrenchment or redundancy—raising further concerns for their mental health and wellbeing.

Nevertheless, having had a taste of flexi-work arrangements since the pandemic, many Singaporeans now want better work-life balance in future, with a preference for work-from-home as the norm. 34, 35 For these Singaporeans, flexi-work arrangements offer a chance to meet both their work and personal demands on their own terms and in their own space,36 while affording more time with their families and other pursuits—all of which have benefits for mental wellbeing.

Having had a taste of flexi-work arrangements since the pandemic, many Singaporeans now want better work-life balance in future, with a preference for work-from-home as the norm.

Restoring and Strengthening Mental Wellbeing

The pandemic and the measures taken to contain it have wrought significant changes to the Singaporean way of life, and taken a toll on mental wellbeing and life satisfaction.

The Government’s many measures in response to the pandemic, supported by initiatives from the private and people sectors, have primarily been aimed at keeping the public safe, while supporting Singaporeans and cushioning the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, particularly on the economic front. Nevertheless, these efforts may contribute to ameliorating the stressors that COVID-19 has thrown up—although it is not possible to completely assuage every anxiety or concern.

Providing support in areas that matter to individuals, with effective policies and actions paired with consistency and accuracy in messaging, is more likely to produce improved wellbeing. In this regard, Singapore’s relative effectiveness—in containing the outbreak, in providing relief to vulnerable groups, and in ensuring that essential supplies are stockpiled and well distributed—does contribute to the public’s peace of mind and hence mental wellbeing.

Providing support in areas that matter to individuals, with effective policies and actions paired with consistency and accuracy in messaging, is more likely to produce improved wellbeing.

It is worth considering if more might be done to make mental wellbeing an explicit area of attention in a crisis, alongside economic and other concerns. Time will tell if enough was done to enable Singaporeans to emerge from this pandemic as a more resilient people and more united citizens, standing firm in the knowledge that we look after each other in a crisis—not just materially but mentally as well.

NOTES

- The World Health Organization describes mental wellbeing as “a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make

a contribution to his or her community”. See: World Health Organization, “Mental Health: Strengthening Our Response”, March 30, 2018, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response#:~:text=Mental%20 health%20is%20a%20state,to%20his%20or%20 her%20community. - N. Elangovan, “SOS Hotline Receives 30% More Calls during Circuit Breaker Period”, Today, September 15, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/sos-hotline-receives-30-more-calls-during-circuit-breaker-period. - S. Hingorani, “Commentary: Isolated with Your Abuser? Why Family Violence Seems to Be on the Rise during COVID-19 Outbreak“, CNA, March 26, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/ commentary/coronavirus-covid-19-family-violence-abuse-women-self-isolation-12575026. - CNA, “COVID-19: MSF Keeping ‘Close Watch’ on Domestic Abuse Cases as More Reach Out for Help over Circuit Breaker Period”, April 23, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/covid-19-msf-domestic-abuse-violence-cases-circuit-breaker-12671330. - C. Yip and R. Smalley, “Home-based Learning Blues: Life in a Rental Flat during the COVID-19 Circuit Breaker”, CNA, April 29, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/cnainsider/home-based-learning-rental-flat-low-income-covid19-12685142. - S. K. Brooks, R. K. Webster, L. E. Smith, L. Woodland, S. Wessely, N. Greenberg, and G. J. Rubin, “The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence”, The Lancet 395 (February 2020): 912–920.

- E. A. Holmes, R. C. O’Connor, V. H. Perry, I. Tracey, S. Wessely, L. Arseneault, C. Ballard, H. Christensen, R. C. Silver, I. Everall, and T. Ford, “Multidisciplinary Research Priorities for the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Action for Mental Health Science”, The Lancet Psychiatry 7 (April 2020): 547–560.

- T. Goh, “One Year after Circuit Breaker, People in Singapore Socialising Less, Working More; Mental Wellbeing Has Declined”, The Straits Times, April 7, 2021, accessed April 12, 2021.

- T. Cheng, S. Kim, and K. Koh, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Subjective Well-Being: Evidence from Singapore”, IZA Discussion Paper, no. 13702, September 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract\_id=3695403#a. - C. A. Heaney, E. C. Avery, T. Rich, N. J. Ahuja, and S. J. Winter, “Stanford WELL for Life: Learning What It Means To Be Well”, Am J Health Promot 31 (5), (2017): 449.

- See Note 10.

- P. Rodriguez Espinosa, Y. C. Chen, C. A. Sun, S. L. You, J. T. Lin, K. H. Chen, A. W. Hsing, and C. A. Heaney, “Exploring Health and Wellbeing in Taiwan: What We Can Learn from Individuals’ Narratives”, BMC Public Health 20, no. 1 (159), February 2020, accessed April 12, 2021, https://www.doi.10.1186/s12889-020-8201-3.

- Ministry of Social and Family Development, “Impact Of COVID-19 On Singaporeans and Supporting Measures”, April 6, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.msf.gov.sg/media-room/Pages/Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Singaporeans-and-Supporting-Measures.aspx. - Prime Minister’s Office, “PM Lee Hsien Loong on the COVID-19 Situation in Singapore on 3 April 2020”, April 3, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/PM-Lee-Hsien-Loong-on-the-COVID19-situation-in-Singapore-on-3-April-2020. - Ministry of Education, “Schools and Institutes of Higher Learning to Shift to Full Home-Based Learning; Preschools and Student Care Centres to Suspend General Services”, April 3, 2020, accessed January 7 2021,

https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/20200403-schools-and-institutes-of-higher-learning-to-shift-to-full-home-based-learning-preschools-and-student-care-centres-to-suspend-general-services. - Ministry of Manpower, “Inter-agency Advisory on Supporting Mental Well-being of Workers under COVID-19 Work Arrangements”, April 24, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.mom.gov.sg/covid-19/inter-agency-advisory-on-supporting-mental-well-being. - Made for Families, “Made for Families”, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.madeforfamilies.gov.sg/MadeForFamilies/made-for-families-organisations. - CapitaLand, “CapitaLand #MealOnMe”, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.capitaland.com/international/en/about-capitaland/sustainability/capitaland-hope-foundation/our-programmes-and-projects/ support-for-communities-affected-by-covid19/CapitaLandMealOnMe.html. - Y. H. Goh, “Coronavirus: Community Self-help Groups Step Up Assistance Schemes”,

The Straits Times, May 14, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/community-self-help-groups-step-up-assistance-schemes. - Mendaki, which caters to the Malay-Muslim community, found almost 5% of grant applications were resubmissions requesting a higher subsidy tier for tuition fees due to a change in household income amid the outbreak. Similar trends were reported in the Chinese Development Assistance Council, the Singapore Indian Development Association, and the Eurasian Association.

- Singapore Department of Statistics, “Key Household Income Trends, 2020”, accessed April 12, 2021,

https://singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/household-income/ visualising-data. - Economic Development Board, “Singapore Budget 2020: COVID-19 Relief Measures for Singaporeans and Businesses”, June 23, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www. edb.gov.sg/en/business-insights/insights/singapore-budget-2020--covid-19-relief-measures-for-singaporeans.html. - S. Yuen, “Covid-19 Support Grant Extended; More Eligible for $3,000 Workfare Payout”,

The Straits Times, August 18, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/covid-19-support-grant-extended-more-eligible-for-3000-workfare-payout. - S. Wong, “Insurance Industry Extending Premium Deferment Relief Measures for Policyholders”, The Straits Times, September 18, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/insurance-industry-extending-premium-deferment-relief-measures-for-policyholders. - Gov.sg, “Call These helplines if You Need Emotional or Psychological Support”, April 23, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.gov.sg/article/call-these-helplines-if-you-need-emotional-or-psychological-support. - Ministry of Health, “Implementing Structured, Comprehensive Strategies to Reduce Mental Healthcare Costs in Public and Private Sectors”, November 3, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.moh.gov.sg./news-highlights/details/implementing-structured-comprehensive-strategies-to-reduce-mental-healthcare-costs-in-public-and-private-sectors. - T. Goh, “Budget Debate: COVID-19 mental health task force to look into post-pandemic needs, develop national strategy”, The Straits

Times, March 5, 2020, accessed April 12, 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/ politics/covid-19-mental-wellness-task-force-will-look-into-post-pandemic-needs-develop. - Institute of Mental Health, “Singapore Mental Health Study (SMHS) 2016”, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.imh.com.sg/research/page.aspx?id=1766. - Ministry of Manpower, “New Taskforce to Enhance Mental Health Care Support for Migrant Workers”, November 6, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-releases/2020/1106- new-taskforce-to-enhance-mental-health-care-support-for-migrant-workers. - Facebook, “Hawkers United —Dabao 2020”, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.facebook.com/groups/HawkersUnited2020/about. - J. South, J. Stansfield, and R. Amlot, “Sustaining and Strengthening Community Resilience throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond”, Perspectives in Public Health 140, no. 6 (August 2020), accessed January 7, 2021,

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ full/10.1177/1757913920949582. - Ministry of Manpower, “Work-Life Grant (WLG) for Flexible Work Arrangements”, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.mom.gov.sg/ employment-practices/good-work-practices/work-life-grant. - N. Meah, “The Big Read: Working from Home Becomes a Nightmare When Lines Are Blurred and Boundaries Trampled”, Today, October 17, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.todayonline.com/big-read/big-read-working-home-becomes-nightmare-when-lines-are-blurred-and-boundaries-trampled. - R. Wee, “Three-quarters of Singapore Employees Expect Work-life Balance to Improve from Flexi-work: Poll”, The Business

Times, October 15, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/government-economy/three-quarters-of-singapore-employees-expect-work-life-balance-to-improve-from. - L. Lai, “8 in 10 in Singapore Want to Work from Home or Have More Flexibility”, The

Straits Times, October 15, 2020, accessed January 7, 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/8-in-10-in-singapore-want-to-work-from-home-or-have-more-flexibility. - Ministry of Manpower, “Tripartite Advisory on Mental Well-being at Workplaces”, accessed May 12, 2021,

https://www.mom.gov.sg/covid-19/tripartite-advisory-on-mental-well-being-at-workplaces.