Leadership at a Time of (Another) Crisis

ETHOS Issue 22, June 2021

Five Traits of Effective Leadership: Are They Enough?

In 2009, as a newly appointed Senior Visiting Fellow with Singapore’s Civil Service College, I arrived in the city-state at a time of crisis. A global financial collapse had triggered recession. There was widespread concern that the event might presage worldwide depression. It was already apparent that the severity and depth of the economic downturn would require bold responses from governments around the world. Public administrators would need to support them with policy advice and delivery.

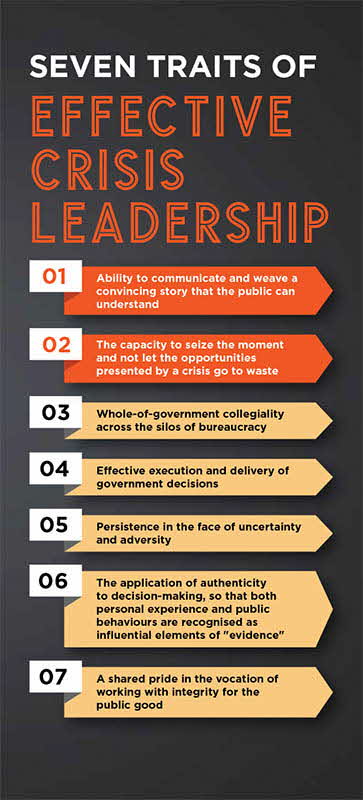

At meetings at the College I was asked what I considered to be the essential qualities of civil service leadership that were needed. In a subsequent article in Ethos (Issue 6, July 2009),1 I identified five characteristics: whole-of-government collegiality across the silos of bureaucracy; effective execution and delivery of government decisions; persistence in the face of uncertainty and adversity; the application of authenticity to decision-making, so that both personal experience and public behaviours are recognised as influential elements of “evidence”; and a shared pride in the vocation of working with integrity for the public good. These attributes implicitly called for emotional intelligence and experiential learning to complement traditional cognitive approaches associated with administrative leadership.

Today the world faces a very different crisis, the potential consequences of which may be even more far-reaching. The global pandemic has forced governments to grapple with how best to protect public health without closing down the economic activity that sustains societal well-being. It’s a difficult balancing act. It requires administrative compromise at many levels, not least between individual freedoms and collective responsibility. To what extent, and for how long, will citizens accept limits on their traditional liberties? How does one maintain public confidence in the tough decisions being taken? How does one ensure that the burdens and benefits of government interventions are seen to be shared equally across society?

Good public servants will communicate more effectively to the extent that they are able to tailor their arguments to government ambitions.

At a time of such pressure, questions abound. What are the elements of public service leadership that come to the fore as societies seek to make urgent decisions in the best long-term interests of the citizenry? On reflection, did I—a decade ago—correctly identify the most important qualities? As we prepare for the post-COVID-19 “new normal”, do I believe additional attributes are required?

Communicating in a Crisis

To my earlier list of five attributes, I would now add two others. One is the ability to communicate. I do not simply mean the capacity to write clearly and speak persuasively. Rather, I mean the ability to weave a convincing story that the public can understand.

Usually it is the role of politicians to craft the political narrative that conveys to the public the reasons for the policy proposals that they espouse or the decisions that they take. In general, the views of civil servants are offered more circumspectly, at least in public. To a large extent they communicate behind closed doors. Their goal is to influence.

In times of crisis, things can change significantly. Senior officials, who may have been almost invisible to the public, can unexpectedly become reluctant national celebrities.

Good public servants will communicate more effectively to the extent that they are able to tailor their arguments to government ambitions. To be apolitical, providing frank and robust policy advice in a confidential and non-partisan manner, does not mean being non-political. A keen understanding of the goals of government can be mightily advantageous to public officials seeking to wield subtle power in a manner that is likely to evoke a positive response from the government of the day. They need to capture the interest (and stoke the enthusiasm) of the minister they serve. A senior civil servant cannot depend exclusively for influence upon the advantage of situational authority.

In times of crisis, things can change significantly. Senior officials, who may have been almost invisible to the public, can unexpectedly become reluctant national celebrities. Ministers, seeking to take challenging potentially unpopular decisions, are tempted to defer (at least in public) to the superior knowledge of their “independent” experts.

In late 2019 and early 2020, when horrendous bush fires raged across much of the Australian landscape, political leaders increasingly left it to the heads of emergency service and first responder organisations to update the media each morning on the dire situation. Presumably, politicians figured that the public had greater confidence in hearing directly from a frontline expert.

In the world of social media, everyone’s opinion is frequently regarded as equally valid. Fortunately, at a time of societal crisis, the value of advice provided by expert public officials can be re-established

Similarly, at the daily updates on COVID-19 presented by the Australian Prime Minister, State Premiers and Territory Chief Ministers, it has become prevailing practice to have the chief medical officers and senior health officials available to answer the detailed questions. It is apparent that a similar approach has been taken in many other democracies, including Singapore.

At a time of crisis, the expertise which always resides among anonymous public servants, and which underpins their ability to formulate evidence-based policy, becomes increasingly visible. The power of effective communication, often honed to convey information and ideas confidentially, now has to be undertaken in the full gaze of media scrutiny.

In general, that’s a good thing. In the world of social media, everyone’s opinion is frequently regarded as equally valid. Expertise is often denigrated as elitist. Celebrity opinion dominates. Conspiracy theories that seem to explain complex events simply can become beguilingly attractive.

Fortunately, at a time of societal crisis, the value of advice provided by expert public officials can be re-established. There is political value in governments acknowledging expertise, both as a means of strengthening public confidence and, on occasion, as a means to defer to others the responsibility for enacting unpopular decisions. The problem is that the public often expects experts to subscribe to a single unchanging opinion. This has become apparent in the present pandemic. One difficult challenge for public officials, whether behind closed doors or in front of a microphone, is to communicate effectively why different experts hold divergent views at different times.

Disruption can be a source of public innovation. In a crisis, there is a heightened willingness to embrace haste and boldness.

That is especially true when expertise is contested. The traditional media will take some pleasure in interviewing academic epidemiologists or senior medical practitioners whose advice is at odds with that presented by public officials (and government ministers). In some instances—for example, on whether or not to wear face masks or the most strategic approach to vaccination—experts may alter their recommendations as more evidence becomes available.

But it can be far harder to convey to the public the differences of opinion that relate to the public policy goal being addressed. It is vital that senior public officials carefully articulate the objectives they are pursuing on behalf of government. Is the intention to manage or to eliminate the virus? Is the priority to minimise COVID-19- related deaths, to lessen pressure on the public health system or to alleviate the broader detrimental impact of lockdowns or loss of employment on the mental health of the community?

In short, civil service leadership requires the capacity to communicate clearly the political objectives that determine the expert advice being provided. Citizens will look to officials for answers but administrators need first to explain more precisely the questions that they are being asked. Unless public purpose can be accurately conveyed, it is difficult for citizens to judge success.

Finding Opportunity in Crisis

A final and most vital attribute of leadership at a time when civil society is under severe challenge is the capacity to seize the moment. Do not let the opportunities presented by a crisis go to waste. At a time of worldwide dislocation and fear, there are opportunities for democratic governments to act in ways that would have been less possible, or been achieved more slowly, in normal times. Outcomes can be achieved that might otherwise have been considered too ambitious. Decisions can be made fast, that might previously have involved years of careful bureaucratic negotiation. Disruption can be a source of public innovation. But it requires public service leaders with the insight, fortitude and capacity to recognise and pursue the chances that emerge and to imagine the future that might be created.

Necessity can be the mother of invention—but only if there are leaders able to structure inventiveness to the public good.

Public sector leaders can take advantage of the greater flexibility of decision-making at times of crisis. The processes generally associated with the interactive processes of public administration can be hastened, even on occasion circumvented. Government, organisations and society are more open to change. In a crisis, there is a heightened willingness to embrace haste and boldness.

Necessity can be the mother of invention—but only if there are leaders able to structure inventiveness to the public good. Sometimes this may best be achieved through new or enhanced government programmes. Often it simply requires government to establish the policy settings that enable and encourage innovative market responses.

In many key areas of the economy, such as retail, the pandemic has accelerated and accentuated the profound shift to online transaction and interaction that was already underway. In other sectors, such as tourism or international education, the pandemic has thrown up barriers to international travel which will not quickly be overcome. More generally, the disruption to the global flow of labour is likely to have significant medium-term impact on population growth and skills shortages in migrant-dependent countries like Australia or Singapore.

The pandemic has generated other economic disruptions. COVID-19 has brought us the Zoom era and expectations of a digital workplace that are likely to outlive the pandemic. The move to allow white-collar employees to work from home has the potential to change working habits, office and building design, public transport provisions and even residential preferences. Online employment skills can be harnessed from around the digitalised world.

Public service leaders need to assess how such developments can be guided by governments to the most socially beneficial outcomes.

At the same time, the public expectations created by crisis have to be managed carefully. In many countries, including Australia, the scale of government financial intervention would have been unimaginable at the beginning of 2019. It will be tempting for governments to maintain higher levels of expenditure (and, in effect, place the cost burden on future generations) rather than to return to the financial stringency of balanced budgets.

Public administrators will need to seize the challenges of crisis and transform them into longer-term opportunities to create public benefit.

As we have learnt from behavioural economics, the public is much better at assessing immediate effects than future consequences. Public servants, and the governments they serve, will need to consider not just how to capture the beneficial opportunities of crisis but how to lower public expectations that the crisis-driven level of government spending can be sustained.

In such, and countless other ways, public administrators will need to seize the challenges of crisis and transform them into longer-term opportunities to create public benefit. That will require leadership, of the sort I have summarised in this checklist of seven traits. Perhaps this may serve as Seven Ways for Civil Servants to Exert Most Influence on the design and delivery of their governments’ capacity to build a new and better post-COVID world.

NOTE

- Peter Shergold, “Leadership at a Time of Crisis”, Ethos 6 (2009): 5–10, https://www.csc.gov.sg/ articles/leadership-at-a-time-of-crisis.