Fiscal Responses to COVID-19 in Singapore and Hong Kong

ETHOS Issue 22, June 2021

Introduction

In many advanced countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted unprecedented fiscal responses to support businesses and households through the crisis, especially during the lockdowns enacted to slow the spread of the virus. Through public finance and national budgets, governments have sought to provide short-term relief and stave off the economic scarring that could arise if mass bankruptcies and unemployment were to occur.1 Some governments have also taken the opportunity in their crisis budgets to accelerate developments in technology and social support systems, laying the foundation for a more digitalised economy and society ready to grasp growth opportunities once the pandemic subsides.

Singapore and Hong Kong—two small and open Asian economies that have often been compared—have both been deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, Hong Kong’s economy contracted by 6.1%—worse than in the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis,2 while Singapore’s economy contracted by a record 5.4%.3

Nevertheless, the overall fiscal responses of the two governments show that small economies can still act effectively in a crisis to support their economies and societies. Fiscal prudence (generating reserves) and discipline (spending control) in past years have afforded them the resources needed to ameliorate the adverse economic impacts of a crisis without taking on substantial debt.

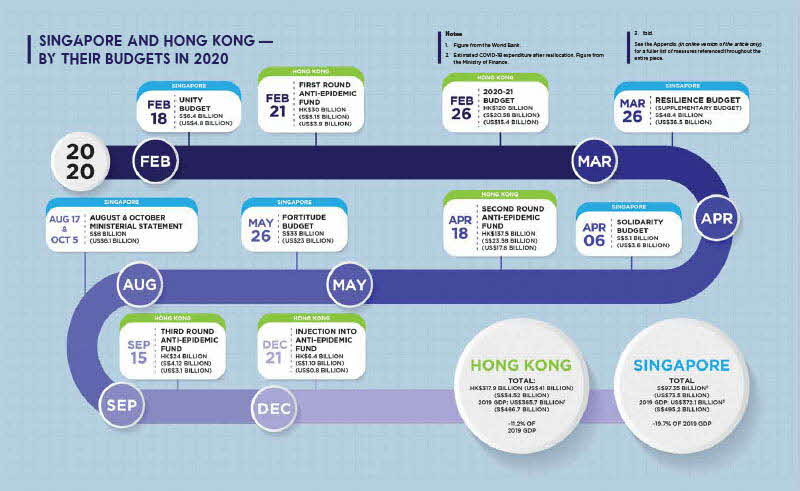

Singapore’s initial fiscal response to COVID-19 in 2020 involved multiple budgets amounting to more than 19% of Singapore’s 2019 Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and drawing on part of its national reserves. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) also dipped into their reserves in order to mount their pandemic response, which came up to about 11% of 2019 GDP.

Both Hong Kong and Singapore have been able to make investments beyond the urgent needs of the pandemic, to be ready for the future that might emerge after the crisis.

Supply-Side and Demand-Side Priorities

The economic crisis brought about by the pandemic has involved both supply and demand shocks. Safety measures aimed at curbing the spread of infection forced stoppages on many business operations. In some instances, business stoppages were also transmitted across borders, such as when restrictions in China led to stoppages elsewhere in the supply chain. Restrictions on tourism and dining, as well as anxiety over income loss and economic uncertainty, also meant greatly reduced demand.

Public financing measures were targeted at both aspects of the ensuing economic shock: reducing the cost burden of operating businesses through “supply-side” policies such as reducing taxation, and boosting consumption through “demand-side” policies such as subsidies or direct cash grants.4

A comparison of measures across governments indicates that the amounts allocated to supply-side measures such as stabilising businesses were substantially higher than demand-side measures such as supporting households and the vulnerable. This was due in part to the fact that consumption-based activities such as retail, travel and dining were often not possible because of safety measures. The Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 had also shown the importance of furlough schemes to reduce economic scarring during a period of sudden market decline.

Supply-side policies to support businesses have been widely adopted in many countries, and demand-side measures tend to be politically popular. However, in a pandemic, governments have to strike a tough balance between different and often competing priorities such as disease control, economic activity, and fiscal sustainability. For instance, encouraging domestic tourism or consumption to keep businesses going contradicts the public health precaution of reducing human contact. In Japan, for instance, the relationship between the “Go To Travel” domestic tourism campaign and their third wave of COVID-19 has been a point of heated debate.5

Singapore and Hong Kong have been able to commit resources to these different goals, prioritising economic stabilisation, while attending to both supply and demand concerns.

Public financing measures were targeted at both aspects of the ensuing economic shock: reducing the cost burden of operating businesses through “supply-side” policies, and boosting consumption through “demand-side” policies.

Public Financing in a Crisis: Key Aims

Musgrave’s (1956) classical work on public finance theory frames government budgets as having three purposes: (1) provision of public goods; (2) distribution of resources; and (3) stabilisation, i.e., maintaining high levels of employment and price stability. The fiscal measures deployed to address the economic impact of COVID-19 might be described as geared primarily towards stabilisation; however, allocation and distribution measures also played a part in reducing the negative economic impact on businesses, households, and individuals.

Stabilisation

During the COVID-19 pandemic, economic stabilisation was a top priority for both Singapore and Hong Kong. Fiscal responses towards this end often took the form of wage subsidies for companies and training programmes to help redeploy those laid off from the worst-hit industries, thereby reducing the unemployment rate. Support was also given to businesses that would have not been viable under the pandemic—in the form of bridging loans to address short-term liquidity issues. Such measures helped stabilise companies, reduced corporate closures and saved jobs. By injecting state credit and liquidity into markets, both governments also sought to maintain confidence in the overall economy.

The measures from both governments did keep unemployment relatively low: in the fourth quarter of 2020, Singapore’s unemployment rate was at 3.3%1 while Hong Kong’s unemployment rate was at 6.6%.2

Distribution

The poor were much more adversely affected by the pandemic. Some weaknesses of modern society had been exposed by the unprecedented crisis as family support was not sufficient for individuals to cope with the negative shocks.

The pandemic highlighted vulnerabilities and inequalities in societies the world over. Both Singapore and Hong Kong SAR governments intensified distributive measures to help cushion the financial difficulties associated with the economic downturn due to COVID-19. A range of social programmes were introduced to address the situation of the less privileged. These included direct unconditional cash transfers, increases in government matching funds for donations, as well as support towards digital adoption and bridging the digital divide.

Provision of Public Goods

Both Singapore and Hong Kong strengthened public goods provision, particularly in bolstering their healthcare systems to cope with the pandemic. This included enhancing the capacity to test for and treat COVID-19 cases, expanding quarantine and isolation facilities, and providing for related needs such as protective masks, vaccinations and mental wellbeing.

Notes

- Ministry of Manpower, “Summary Table: Unemployment”, April 28, 2021, accessed May 21, 2021, https://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Unemployment-Summary-Table.aspx.

- Reuters, “Hong Kong Fourth-Quarter 2020 Unemployment at 16-Year High, Hit by Economic Slowdown”, Yahoo! Finance, January 19, 2021, accessed May 21, 2021, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/hong-kong-fourth-quarter-2020-091316621.html.

Supporting Businesses

In Singapore and Hong Kong, a number of fiscal measures were deployed to help businesses tide over the pandemic. In particular, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) were a priority for support, since they are important to both economies: Singapore SMEs accounted for about 45% of local GDP and 65% of the workforce in 2020,6 while Hong Kong’s SMEs contributed to over 50% of local GDP in 20127, 8 and 45% of the private sector workforce in 2020.9

Both governments provided loan support for businesses (such as an SME financing guarantee scheme), in particular making short-term liquidity available during periods of lockdown. The Singapore Government introduced a Temporary Bridging Loan Programme in the 2020 Unity Budget: this was subsequently enhanced in the Resilience and Solidarity Budgets 2020. Under the programme, the Government took on the majority of the risk of loans given to companies by participating financial institutions. The financial firms would still bear some risk, which gave them incentive to continue performing proper credit assessments and lending only to enterprises capable of repaying the loans. While the Government provided loan capital, the Monetary Authority of Singapore also provided a facility (0.1% rate) for participating financial institutions to tap on, to manage the interest rate being charged.

To save jobs, the Singapore Government co-funded between 25% and 75% of the first S$4,600 of gross monthly wages of local employees for up to 23 months, under the Jobs Support Scheme.

Support levels were differentiated based on the projected impact of COVID-19 on different sectors, with firms in the tourism, hospitality, aviation, and aerospace sectors receiving the highest levels of support.

The Singapore Government also granted property tax rebates for commercial and industrial properties. Commercial properties such as shops received a 100% rebate, while non-residential properties (such as offices and industrial properties) received a 30% rebate. Property owners were also required to pass these benefits on to their tenants.

Hong Kong offered smaller property tax rebates, taking a granular and differentiated approach in assisting companies from different industries. For example, for the companies related to the aviation, tourism, and transport industries, there were several rounds of industry-targeted subsidies.10 In addition, Hong Kong also offered targeted support for industries directly affected by the government's social distancing measures, including subsidies and relief grants for the convention and exhibition industry, tutorial and private schools, school caterers, and school bus providers.

Such business support measures played a stabilising role in reducing job losses, by allowing companies to keep more of their workers instead of retrenching them. These measures also likely reduced the number of corporate closures—more companies were able to keep afloat and at least maintain some level of operations even with the lockdowns.

Support for Households

An important aspect of fiscal responses to the pandemic has been the extension of support to households. During crisis periods, households face the prospect of a drop in income from a decline in business, wage cuts or job losses. As a result, households might find themselves in financial distress. Government support for household activities can become vital for maintaining their wellbeing; bolstering household consumption also in turn generates demand and fuels the economy. Some of these demand-side fiscal measures might take the form of subsidies for individuals and households, in addition to supply-side measures such as reducing taxation and government fees.

Hong Kong rolled out several subsidies for individuals and households. For example, under the 2020–21 budget, all Hong Kong permanent residents aged over 17 received HK$10,000, totalling HK$71 billion (S$12.18 billion) in public spending. The Hong Kong SAR government also waived various employment taxes \[Salaries Tax and Tax under Personal Assessment Reduction, with a ceiling of HK$20,000 (S$3,430) at an estimated cost of some HK$18.8 billion (S$3.22 billion)\] in lost revenue. Given that property was a substantial asset for many Hong Kongers, the government also offered a Residential Properties Rates Waiver, totalling HK$13.3 billion (S$2.28 billion).

There was also policy support for job retention—the Employment Support Scheme costing HK$92.4 billion (S$15.85 billion) provided financial support for employers to retain workers for about 150,000 employers from June to August 2020. There were also programmes established to entice employment for older workers and youth, with on-thejob training allowance provided to employers.

Singapore also provided tax relief for households and individuals. For self-employed people and low-income workers, pandemic-driven support schemes included the Self-Employed Person Income Relief Scheme and Workfare Special Payment. There were also schemes, such as the SGUnited Jobs and SGUnited Traineeships, to help job seekers find jobs and boost employability for fresh graduates. To encourage firms to accelerate their hiring of local workers, the Singapore Government also provided a wage subsidy for each eligible new local hire under the Jobs Growth Incentive.

Singapore's measures in the job market remain ahead of other regional cities in supporting local workers most affected by COVID-19. It continues to provide enhanced upskilling and employment facilitation support, with a focus on moving workers into economic activities expected to grow after the pandemic.

Singapore's measures in the job market focus on moving workers into economic activities expected to grow after the pandemic.

Support for the Less Privileged

Across the world, fiscal measures have been deployed to support the less privileged during the pandemic. Many governments expanded existing safety nets to maintain social resilience. While some developed countries, such as Australia, offered additional unemployment benefits in addition to existing social security provisions,11 unemployment support provisions have been largely absent in many developing countries where a substantial amount of people work in the informal sector.12

Singapore’s social support during the pandemic was provided on several fronts. There were universal cash payouts on a progressive scale from S$600 to S$1200, with more affluent individuals receiving less assistance. Additional cash payouts were given to Singaporeans aged 50 years and above, and to parents with young children. Singaporeans living in smaller public housing flats were given grocery vouchers, and there was also additional funding for various social support agencies. Singaporean households in all residential property types received a one-off S$100 utilities credit, with HDB households also receiving double their regular GST Voucher–U-Save (utilities rebates), and larger households receiving 2.5 times their regular U-Save. HDB households also received rebates to help offset estate service and conservancy charges. The COVID-19 Support Grant was also introduced for people who lost their jobs or experienced significant income losses because of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the Singapore Government provided Meal Subsidies for Children, costing up to S$2 million (in matched funding).13 In total, the benefits and assistance disbursed lowered Singapore’s Gini coefficient from 0.398 in 2019 to 0.375 in 2020, after accounting for government taxes and transfers.14

During the pandemic, Hong Kong enhanced benefits allocated for the less privileged. For example, the government offered an Extra Allowance for Social Security Recipients—HK$4.225 billion (S$725 million), and a Public Rental Units one-month waiver amounting to HK$1.829 billion (S$313.7 million). Furthermore, the Hong Kong SAR government extended a Special Scheme of Assistance to the Unemployed under the CSSA Scheme for six months, from 1 December 2020 to 31 May 2021 [HK$724 million (S$124.2 million)].15 Short-term Food Assistance Service Projects for poor people [HK$127 million (S$21.8 million)] were added. The Hong Kong SAR government also provided assistance to families with schooling children. With pandemic restrictions obliging school-age children to stay at home for online learning for an extended period, the government provided an Additional Student Study Grant for the 2019/20 school year [HK$876 million (S$150.3 million) during the 1st round] to defray education expenses.

Such measures represented substantive efforts from both the Singapore and Hong Kong SAR governments to provide vital public goods and distribute resources to those who needed them most, reducing social distress.

Support for Technology and Digitalisation Efforts

Even during a pandemic, longer-term technological developments and socioeconomic shifts continue to unfold. Both Hong Kong and Singapore have been able to make investments beyond the urgent needs of the pandemic, to be ready for the future that might emerge after the crisis, as uncertain as it seems.

In the technology sector, the Singapore Government promoted a Startup SG Equity (a S$300 million injection) to boost private investment (S$800 million of private funding over the next decade expected) in emerging deep technology sectors, such as advanced manufacturing and agri-food technology. In addition, measures such as the Digital Resilience Bonus, support for digitalisation partnership, the enhanced Startup SG Founder programme, and recurrent National Innovation Challenges signalled an accelerated and determined focus on the medium- to long-term advancement of Singapore’s digital economy.

At the grassroots level, the Singapore Government provided a bonus of S$300 per month over five months to encourage stallholders in hawker centres, wet markets, coffee shops, and industrial canteens to use digital payment systems. Singapore’s Ministry of Education brought forward its plans to deliver digital devices for all secondary school students, from the original target date of 2028 to 2021.16 Singapore’s Fortitude Budget also included incentives to help residents, particularly the elderly, learn digital skills and acquire digital devices.17 Such measures were timely, given that the pandemic and healthcare precautions had prompted a shift from physical to digital services and transactions across many industries.

The Hong Kong SAR government also provided support for digital efforts, albeit at a smaller scale than Singapore’s initiatives. Support included a Subsidy for Encouraging Early Deployment of 5G [HK$55 million (S$9.43 million) in the 2nd round], a Distance Business Programme [HK$1.5 billion (S$273.3 million) in the 2nd round\] to support businesses adopting information technologies, and a COVID-19 Online Dispute Resolution Scheme to support online resolution of disputes [HK$70 million (S$12.0 million) in the 2nd round].

Both Hong Kong and Singapore have been able to make investments beyond the urgent needs of the pandemic, to be ready for the future that might emerge after the crisis.

Singapore and Hong Kong — Differences in Approach

While both Singapore and Hong Kong targeted similar areas of concern in their fiscal responses to the pandemic, their approaches differed in substantive ways.

Hong Kong took a granular approach, extending one-time support to businesses most directly affected by the pandemic.

Businesses that typically rely on in-person services were subsidised to continue operating. These included beauty and massage parlours, gambling and gaming facilities, nightclubs, tourism-related businesses and conventions facilities, as well as childcare and private tuition centres.

In contrast to Hong Kong’s approach of micro-targeting of subsidies and support, Singapore categorised industry clusters by need, defining different tiers according to the level of intervention required. For instance, Singapore identified the aviation, tourism and hospitality industries as having suffered the largest impact, and thus needing the most support. The next tier of concern included the food services, such as food shops and hawker stalls, as well as retail, arts and entertainment, land transport, and marine and offshore sectors. At different points, other sectors were identified for tiered intervention. For instance, the built environment sector temporarily joined other sectors, receiving the highest tier of support (75% wage support) from June to August 2020.

Singapore and Hong Kong also differed in their policy support for workers' skills training, especially for the self-employed. Hong Kong's policies were again microtargeted according to their industry, while Singapore took a broad-based approach, in which training funds were offered irrespective of industry in order to facilitate demand-led reallocation. On the whole, Singapore has been able to provide more support in skills training and for the self-employed during this pandemic. It has expanded the range of training and employment opportunities for workers by creating traineeships, apprenticeships and jobs.

In contrast to Hong Kong’s approach of micro-targeting of subsidies and support, Singapore categorised industry clusters by need, defining different tiers according to the level of intervention required.

Conclusion

Despite pressing challenges and prevailing uncertainty, long-term fiscal discipline has afforded both Singapore and Hong Kong the capacity to act decisively in supporting and stabilising their economies and societies in this crisis so far, through both supply and demand side measures. Public spending on the less privileged and households in Singapore and Hong Kong has cushioned the worst impacts of the pandemic.

Even as they addressed the urgent challenges of the present, both governments have been able to invest in the future, offering businesses the means to change their operating practices and adopt new business models through digitalisation, while also providing employees with the means to retrain to be more productive and more employable to new growth industries. While the pandemic is far from over, both economies look set to resume their growth trajectories once the crisis subsides.

APPENDIX: SOURCES FOR BUDGETS

- Ministry of Finance, Republic of Singapore, Budget Speech, 2020, https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget\_2020/budget-speech (subsequently referred to as, "Unity Budget").

- Ministry of Finance, Republic of Singapore, Resilience Budget, 2020, https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget\_2020/resilience-budget.

- Ministry of Finance, Republic of Singapore, Solidarity Budget, 2020, https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget\_2020/solidarity-budget.

- Ministry of Finance, Republic of Singapore, Fortitude Budget, 2020, https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget\_2020/fortitude-budget.

- Ministry of Finance, Republic of Singapore, Ministerial Statement—Aug 2020, 2020, https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget\_2020/AugustStatement (as a statement in August, it was commonly referred to as the "August Ministerial Statement").

- Ministry of Finance, Republic of Singapore, Ministerial Statement—Oct 2020, 2020, https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget\_2020/ministerial-statement-oct-2020 (as a statement in August, it was commonly referred to as the "October Ministerial Statement").

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, First Round of $30 billion Anti-Epidemic Fund, 2020, https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/anti-epidemic-fund-1.html.

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, $120 Billion Relief Package in the 2020–21 Budget, 2020, https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/anti-epidemic-fund-1.html.

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Second Round of $137.5 Billion Anti-Epidemic Fund, 2020, https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/anti-epidemic-fund-2.html.

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Third Round of $24 billion Anti-Epidemic Fund, 2020, https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/anti-epidemic-fund-3.html.

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, An Injection of $6.4 Billion into the Anti-Epidemic Fund, 2020, https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/anti-epidemic-fund-4.html.

NOTES

- “Economic scarring” here refers to the protracted duration of recovery of the economy to pre-crisis periods, evident in indicators such as unemployment rates.

- E. Lam, “Hong Kong’s Economy Contracts Record 6.1% in Pandemic Year”, Bloomberg, January 29, 2021, accessed February 15, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-28/hong-kong-faces-difficult-road-to-recovery-after-record-slump.

- C. Lin and A. Aravindan, “Singapore on Path to Recovery as Q4 GDP Shrinks Less than Estimated”, Reuters, February 15, 2021, accessed February 28, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-singapore-economy-gdp-idUSKBN2AF02R.

- Fiscal measures are regarded as "demand-side" when they are aimed at boosting aggregate demand, such as funding provided for social or corporate consumption. On the other hand, "supply-side" measures are those that focus on relaxing regulation or reducing taxation and other fees.

- R. Takahashi, “Japan to Suspend Go To Travel Program Nationwide from Dec. 28 to Jan. 11”, The Japan Times, December 14, 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/12/14/national/suga-go-to-travel-coronavirus/.

- Asian Development Bank, “2020 ADB Asia SME Monitor—Singapore”, 2020, accessed April 30, 2020, https://data.adb.org/media/7281/download.

- Ipsos Business Consulting, “Connected Hong Kong SMEs: How Hong Kong Small Businesses Are Growing in the Digital Economy”, February 2014, accessed March 15, 2021, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/2017-07/Connected-HKSMEs\_Report\_10-Feb-2014.pdf.

- More recent data unavailable.

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Trade and Industry Department, “SUCCESS—SMEs in HK”, September 2020, accessed March 15, 2021, https://www. success.tid.gov.hk/english/aboutus/sme/service\_ detail\_6863.html.

- These included the Subsidy for the Aviation Sector (HK$343 million in the 2nd round); a Subsidy Scheme for the Transport and Aviation Sector (HK$250 million in the 3rd round); Licensed Guesthouses Subsidy Scheme (HK$150 million, 1st round); a Travel Agents Subsidy Scheme (HK$138 million in the 1st round; HK$397 million in the 3rd round).

- J. Andrew, M. Baker, J. Guthrie, and A. Martin- Sardesai, “Australia's COVID-19 Public Budgeting Response: The Straitjacket of Neoliberalism”, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 32, no. 5 (2020): 759–770, https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-07-2020-0096.

- B. Upadhaya, C. Wijethilake, P. Adhikari, K. Jayasinghe, and T. Arun, “COVID-19 Policy Responses: Reflections on Governmental Financial Resilience in South Asia”, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 32, no. 5 (2020): 825–836, accessed December 31, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-07-2020-0130.

- Ministry of Education, “Supporting Students in Financial Need: School Meal Subsidies to Continue Till End of Circuit Breaker Extension”, May 3, 2020, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/20200503-supporting-students-in-financial-need-school-meal-subsidies-to-continue-till-end-of-circuit-breaker-extension.

- Hwee Min Ang, “Record Low in Income Inequality Due to ‘Massive Transfers’, Schemes Tilted towards Lower-Income Groups: Heng Swee Keat”, CNA, February 21, 2021, accessed March 15, 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/budget-2021-heng-swee-keat-forum-record-low-income-inequality-14250068.

- CSSA stands for Comprehensive Social Security Assistance Scheme—Hong Kong SAR Government’s main means-tested social support programme for families and individuals whose income and assets lie below the set amount.

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, “National Broadcast by SM Tharman Shanmugaratnam on 17 June 2020”, June 17, 2020, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/National-Broadcast-by-SM-Tharman-Shanmugaratnam-on-17-Jun-2020.

- Budget 2020, “Fortitude Budget Statement”, May 26, 2020, accessed March 15, 2021, https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget\_2020/fortitude-budget/fortitude-budget-statement.