Growing a Biophilic City in a Garden

ETHOS Issue 19, Jul 2018

Evolving Singapore into a Biophilic City in a Garden

Singapore is widely recognised as one of the greenest cities in the world. Once an unsanitary port city, it has become a green and liveable First World metropolis in the span of just a few decades. This remarkable transformation is testament to the farsighted vision and strong political will of Singapore’s leadership, as well as to the efficiency and pragmatism of its governance.

From the beginning, there was clear direction that greenery provision was to be integral to our socioeconomic and national infrastructure development. In 1963, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew directed that a tree planting campaign be launched across Singapore. He personally chaired the Garden City Action Committee, which was set up within the Ministry of National Development in 1970. The Committee would spearhead the formulation of a greening policy, as well as direct, coordinate and monitor the course of the campaign.

Mr Lee felt that making Singapore green was the most visible way to impress upon foreign dignitaries and businessmen that our city-state was well-organised and had a committed and efficient government—a factor that attracted investments into Singapore. But he also saw greening not just as an economic imperative, but as a social leveller. He believed that making greenery accessible to all Singaporeans would give them a shared stake in the country’s wellbeing, and bind them together as one.

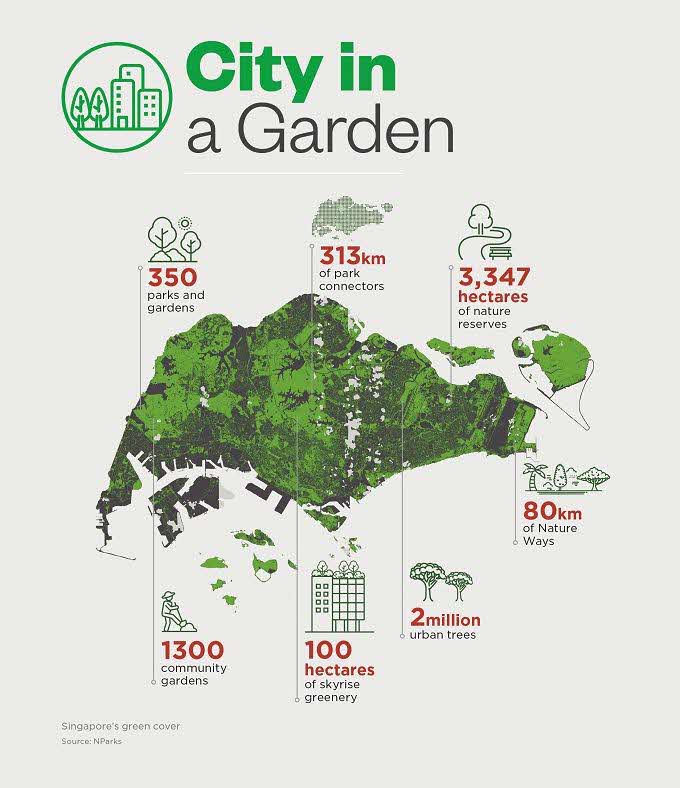

After over 50 years of greening, Singapore is today not just a Garden City, but a biophilic City in a Garden—a green oasis comprising an interconnected network of verdant streetscapes, gardens, parks, nature reserves and vertical greenery. Singapore has transitioned from greenery provision to the development of a sustainable urban ecosystem and a closer affinity with nature in the city.

“Greening raised the morale of the people and gave them pride in their surroundings. We taught them to care for and not vandalise the trees. We did not differentiate between middleclass and working-class areas. The British had superior white enclaves in Tanglin and around Government House that were neater, cleaner and greener than the ’native’ areas. That would have been politically disastrous for an elected government.”

—Lee Kuan Yew1

Establishing the Urban Ecosystem

Source: NParks

Greenery, green spaces and natural habitats continue to be the foundations of our City in a Garden, and are key elements of the landscape matrix that make up Singapore’s urban ecosystem. Over the past decade, we have sought to further connect and enhance these elements, to strengthen the health of the ecosystem. Nature is also better integrated into the built landscape. This is a first step towards building a more biophilic environment. Several key initiatives have brought this to bear.

Benefits of Making Singapore More Biophilic

Safeguarding our nature reserves as refugia of biodiversity

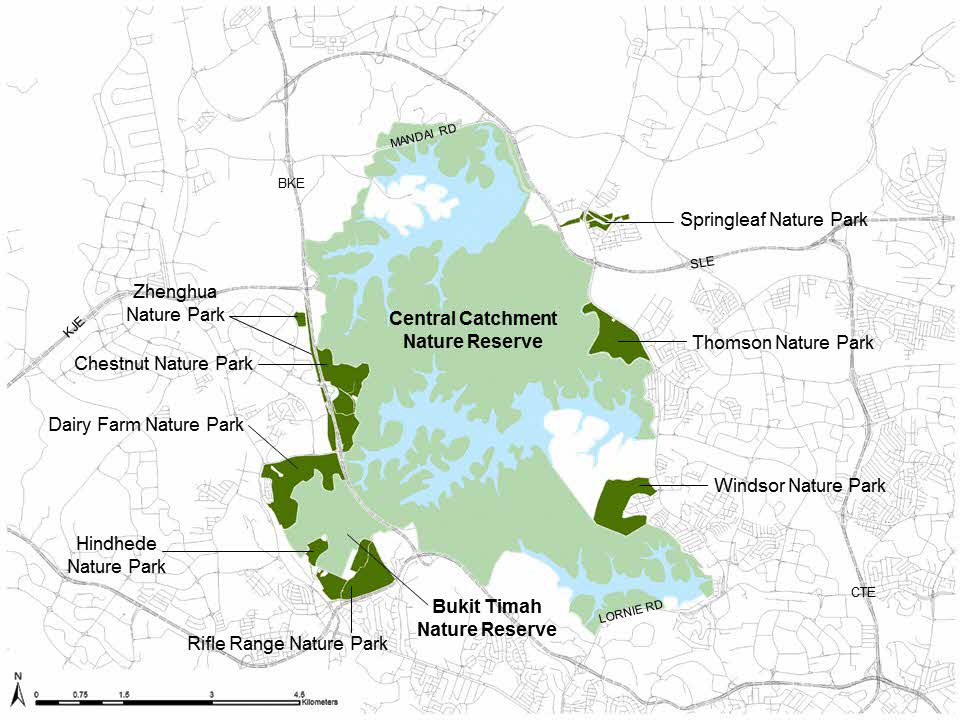

Today, Singapore has in its midst four nature reserves—Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Labrador Nature Reserve. They represent the range of natural habitats forming the main sources of biodiversity: from primary to secondary lowland rainforests to freshwater swamp forest, mangroves and mudflats.

To bolster the resilience of the nature reserves, a network of nature parks has been set up to buffer against the impacts of urbanisation. These parks mitigate edge effects by reducing wind and heat, and serve as barriers against invasive species. They also provide complementary habitats for native biodiversity. More importantly, the parks allow for compatible naturebased recreation, such as hiking, and alleviate visitorship pressure on the nature reserves.

Nature Parks as Buffer Parks

Nature reserves are protected areas of rich biodiversity that are representative sites of key indigenous ecosystems. To safeguard the native flora and fauna in these areas, there are special restrictions on the activities that can be carried out.

As part of a holistic conservation approach, nature parks have been established on the margins of the Nature Reserves to act as green buffers. NParks enhances the habitats within these buffers so that they remain rustic and forested, while serving as an alternative venue for the public to enjoy recreational activities. Nature parks also buffer the nature reserves against developments that abut the reserves. The map below shows the nature parks abutting the Bukit Timah and Central Catchment Nature Reserves. For instance, over at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, a 31-hectare extension to its east acts as its buffer.

Source: NParks

In the same way that we have conserved terrestrial habitats, the Sisters’ Islands Marine Park was established in 2014 to provide a refugia for marine biodiversity. Agent-based modelling demonstrate that Singapore’s southern islands appear to be a closed system with sea currents pushing out from the Sisters’ Islands. The re-population of corals in the Marine Park means it can serve as a source of coral propagules that could disperse and regenerate other coral populations in the Southern Islands.

Enhancing ecological connectivity across the island

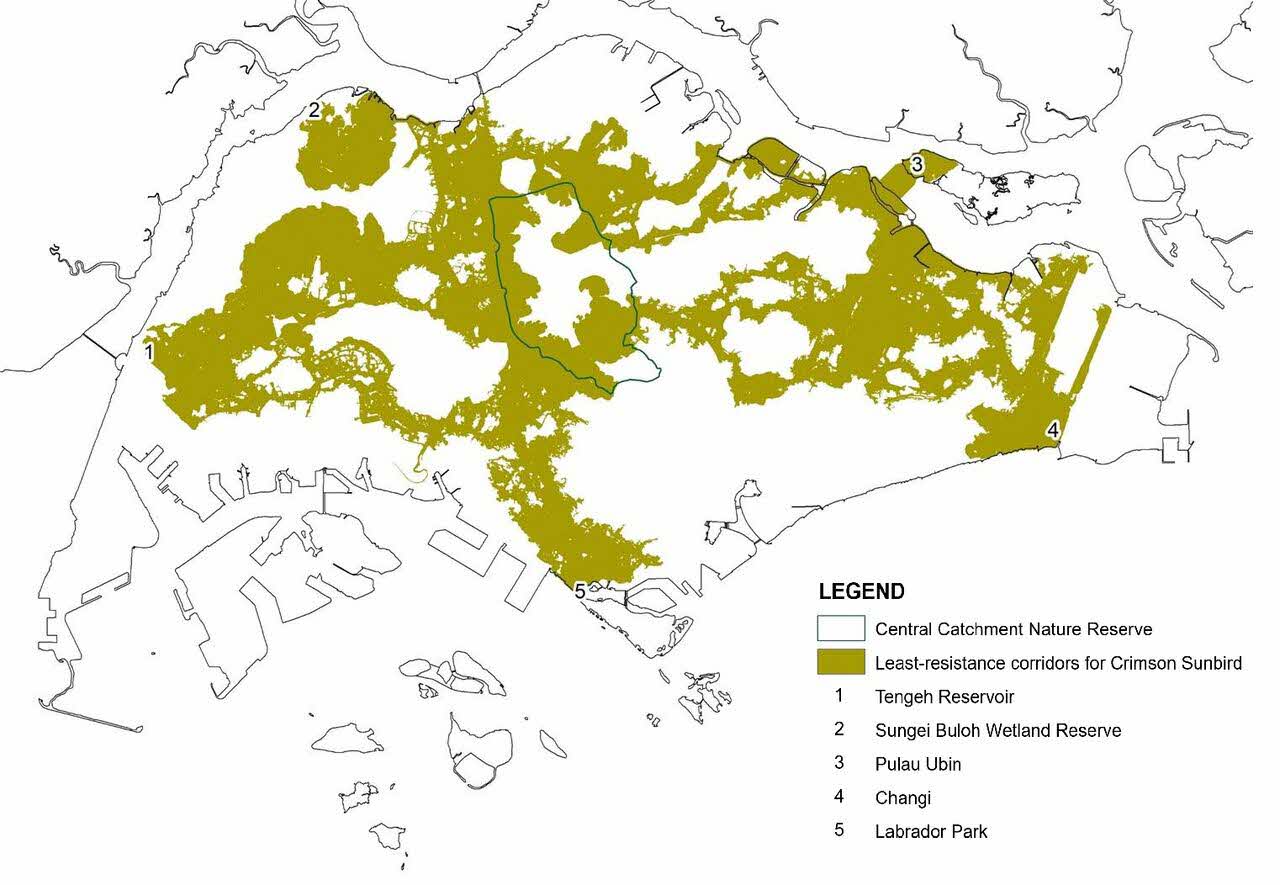

To further build up the resilience of the urban ecosystem, we have started to focus on ecological connectivity between areas of high biodiversity in Singapore. Least resistance pathways for fauna have been modelled using GIS (Geographic Information System) technology to identify corridors that will allow east-west and north-south ecological connectivity via the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, as well as coastal connectivity in the northern and southern coasts. These corridors include nature ways and park connectors. The park connectors and nature ways take the form of forest garden landscapes and are planted with a diversity of native flora. Special attention is placed on native birds and butterflies. Within these corridors, natural habitats within parks are further enhanced so that they become important ecological “stepping stones” for native biodiversity.

Source: NParks

Previously a concrete canal, the stretch of Kallang River running through Bishan–Ang Mo Kio Park has been transformed through a joint collaboration between NParks and PUB, under the ABC Waters Programme. Today, it is a lush meandering natural river that not only functions as a floodplain, but is also an attractive place for people to enjoy and wildlife to thrive.

Determination of Ecological Networks in Singapore

To enhance ecological connectivity, the National Parks Board worked with the Urban Redevelopment Authority and National University of Singapore to identify ecological networks to connect habitat patches in the landscape. The researchers incorporated ecological information of target fauna species through multiple-criteria decision analytics into GIS models, and projected ecological networks that animals are likely to use. The researchers have also developed landscape planning design guidelines to incorporate this ecological network into urban greening plans.

Example of least-resistance corridors for the Crimson Sunbird

Source: NParks, Urban Redevelopment Authority and National University of Singapore

Ecological connectivity, however, does not merely mean providing for the movement of biodiversity. It is also about restoring ecological processes, such as waterways and groundwater, so that sustainable cycles can continue to function within the ecosystem. A major step in this direction is national water agency PUB’s Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters (ABC Waters) Programme, in which seamless land-water interfaces are created by naturalising canal walls.

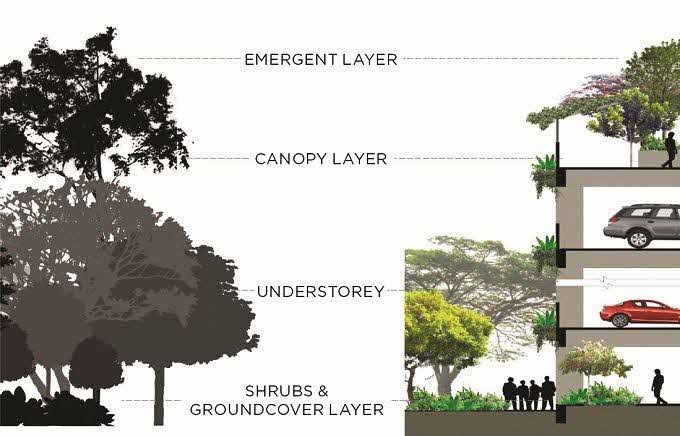

Replicating a naturalistic structure within the urban landscape

Having established the nature reserves, nature parks and ecological corridors within the landscape, it is equally important that they are re-vegetated to replicate the structure of the tropical rainforest. This brings about a landscape more amenable to living in an equatorial climate. It reduces the heat island effect generated by urban development and further ensures a more sustainable landscape.

Over the last decade, more species of native trees and shrubs have been introduced, some of which have been propagated from seeds collected from within our native habitats. Plantings along streetscapes and parks are now more natural in look, with the adoption of a tiered structure. This extends into the built environment in the form of vertical and rooftop gardens that mimic epiphytic plants that adorn the trunks of dominant trees and emergent tree cover respectively.

Replicating the tropical rainforest structure in our urban landscape

Source: NParks

Restoring and curating habitats in the city

Beyond the physical development required in establishing the ecosystem, a restoration programme is underway to enhance habitats within our urban gardens and parks. A species recovery programme targeted at almost 100 flora and fauna species under threat is also beginning to yield results in rescuing species that were once thought to be extinct or at the brink of extinction. There are also efforts to better curate landscapes to provide a more immersive experience with nature. The recently completed Singapore Botanic Gardens Learning Forest is an example of this. A historical water catchment was reinstated, restored and curated as a lowland forest and wetland habitat. As an extension of this work, we have also pioneered the design and development of nature-inspired therapeutic gardens and are now working on biophilic playscapes.

Recovery of Species under Threat

Under NParks’ species recovery programme, specific conservation strategies are developed and employed to help recover the populations of endemic, rare or threatened native species in Singapore. There have been encouraging results in some cases, such as that of the Oriental Pied Hornbill. These cases give hope that with concerted effort, we can help our currently vulnerable species to recover and thrive as well.

Oriental Pied Hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris)

Source: NParks

The Singapore Hornbill Project started in 2004 as a collaboration by a few naturalists with the National Parks Board and Jurong Bird Park. Artificial nest boxes were installed throughout the island for the hornbills to breed. During the study, high-tech sensors and CCTVs were installed to monitor and record the hornbills’ breeding behaviour. The study and provision of these artificial nest boxes and improved habitats have led to the increase in the hornbill population from a few individuals on Pulau Ubin in 1994, to about 100 throughout Singapore at present.

Singapore Hornbill Project - Return of the King

Source: NParks

Singapore Kopsia (Kopsia singaporensis)

Source: NParks

This plant is native to Singapore and bears the same colour as our national flag, earning it its name. It occurs locally in Nee Soon Freshwater Swamp and has been successfully propagated and reintroduced into our nature reserves, parks and gardens.

Neptune’s Cup Sponge (Cliona patera)

Source: NParks

This species was rediscovered in Singapore’s waters in 2011 after being absent from our waters for more than a century. Ongoing conservation efforts include transplanting individuals to locations that will give them proximity to each other so as to increase the opportunities for them to reproduce sexually.

Singapore Botanic Gardens Learning Forest

The Learning Forest

Source: NParks

The 10-hectare Learning Forest is an extensive restoration project of the lowland forest and wetland habitats that used to surround the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Detailed site surveys were conducted and reference was taken from early 19th century maps to restore these former habitats. The Learning Forest is home to more than 100 species of birds, 20 species of amphibians and reptiles, 19 species of butterflies, 7 species of mammals and over 500 species of plants.

SPH Walk of Giants

Source: NParks

Keppel Discovery Wetlands

Source: NParks

Nurturing a Biophilic Community

Relevance of Biophilia for All Ages

Being a biophilic city goes beyond just having nature in the built environment. It is also about how communities become part of the ecosystem and stewards of nature. From the onset of Singapore’s greening efforts, we have recognised how a virtuous cycle can be established between the flourishing of our green spaces and the enhancement of civic ownership. In the past decade, the community has been at the centre of our work in greening and conservation.

A virtuous cycle can be established between the flourishing of our green spaces and the enhancement of civic ownership.

Through various programmes and opportunities, the NParks community today comprises more than 40,000 volunteers. This involvement has evolved beyond community outreach and participation to active stewardship of our natural heritage.

Seeding community involvement

To nurture community involvement, it is imperative that gardens, parks and nature reserves must first be well-loved. This can only happen if people are learning about them or visiting and appreciating them. Each year, more than 3,000 educational and outreach programmes that cater to an extensive range of interests are organised across various gardens, parks and nature reserves. This shifts the focus from just providing green spaces for respite to activating green spaces to cater to lifestyle needs and wellbeing. Many of these programmes also help to inculcate an interest and passion in greenery, and beyond our green spaces, there are programmes that reach out to schools and neighbourhoods as well.

Being a biophilic city is also about how communities become part of the ecosystem and stewards of nature.

The “Every Child a Seed” programme reaches out to every cohort of Primary Three students in Singapore. The schoolchildren are provided with a plant starter kit so that they can experience the joy of growing their own plants, while learning to appreciate the challenges involved.

A love for gardening is also fostered through the Community in Bloom (CIB) programme, which encourages communities to start up their gardens in public spaces. NParks provides training and horticultural tips, such as how to grow edibles or native plants, to drive interest. This is complemented by the allotment garden programme, where individuals can rent spaces in parks to do gardening.

Citizen science programmes are made available to the public and school groups, engaging the community to participate in scientific research. Data derived from these projects helps to guide conservation strategies and hence involve the community in the conservation of our natural heritage.

Learn about the Community in Bloom and Community in Nature initatives.

Community Initiatives

Source: NParks

Community in Bloom Initiative

- Over 1300 community gardens under Community in Bloom (CIB) programme

- Over 160 groups under CIB Indoor Gardening programme

- 700 allotment garden plots have been launched in 9 parks

Source: NParks

Community in Nature Initiative

Citizen science encourages the public to learn more about our natural heritage, and play an active role in contributing to organised research efforts through the collection of large quantities of data. Awareness of Singapore’s rich natural heritage is raised through public participation in NParks’ Community in Nature Biodiversity Watch Programmes. The programmes encourage stewardship of nature amongst Singaporeans, while concurrently collecting information that will inform the development of long-term conservation management strategies. The Biodiversity Watches include Intertidal Watch, Heron Watch, Garden Bird Watch, Butterfly Watch, Dragonfly Watch and BioBlitzes.

Fostering active stewardship

Partnering with Different Stakeholders to Work towards a Biophilic City

Moving from community participation to active stewardship, the Friends of the Parks initiative is a prime example of how community ownership can bring people together to build consensus, as well as to manage and run programmes in our green spaces. Various stakeholders—ranging from researchers, conservation and heritage enthusiasts to regular park goers —come together to activate and energise each green space, for the benefit of all.

Some in the nature community have also formed working groups to discuss and tackle issues related to conservation and management of several fauna species. These groups generally comprise a variety of stakeholders, including agencies, academics and members of the community. They help raise awareness of human-wildlife interactions, a key aspect of nurturing biophilic communities.

To nurture community involvement, it is imperative that gardens, parks and nature reserves must first be well-loved.

Friends of Ubin Network and Otter Working Group

The Friends of Ubin Network (FUN) was formed in 2014, and comprises a broad network of stakeholders who are passionate about Pulau Ubin, are keen to share their ideas and to take personal action by being involved in initiatives and projects. They include biodiversity experts, conservation activists, history buffs, socio-anthropologists, students, volunteers and Ubin community leaders and residents.

The Network’s discussions centre around five broad themes: Biodiversity conservation, Heritage, History and Community, Sustainable Design & Practices, Education & Research, and Nature-based Recreation. The aim is to develop ways to further enhance the island and get more Singaporeans involved.

For example, FUN members have developed a code of conduct for environmentally and socially responsible behaviour on Pulau Ubin. Known as the “Ubin Way”, the code of conduct was inspired by the kampung spirit that Pulau Ubin residents embody and is centred on the innate motivation to care for the environment.

Source: NParks

Otter Working Group

Established in April 2016, the group comprises members from non-governmental organisations, government agencies, academics, Otterwatch (a community volunteer group), as well as individuals. The group monitors movements of the native otters around Singapore, meets with stakeholders to resolve otter issues, and actively educates the public on otters and what to do when they encounter them.

In November 2017, the group successfully isolated, treated and released an otter that was injured by a rubber ring around its body, in an operation that was the first of its kind in Singapore. The success came after three weeks of detailed planning, observations and attempts, and required the support and expertise of various members of the working group—from insights on otter behaviour to technical knowledge of how to build a corral structure.

Source: NParks

Towards the future

NParks received the UNESCO Sultan Qaboos Prize for Environmental Preservation in October 2017 in recognition of its efforts in promoting biodiversity conservation in a highly urbanised and land scarce citystate. Through its Nature Conservation Masterplan (NCMP), it has conducted significant conservation biology research that has also resulted in the discovery of new endemic plant and terrestrial invertebrate species, and the results have been used to design better management plans and facilitate science-based decision-making.

The award is a landmark achievement for Singapore. Years of carefully balancing development and conservation has given us a highly liveable city. Growing land constraints and urbanisation will be challenges in the coming years, but they will be met with renewed commitment and innovation. We will draw on our knowledge and experience to further strengthen urban ecosystems, and build community ownership and stewardship, to ensure that we continue to grow a biophilic City in a Garden.

The Challenge of Protecting Singapore’s Natural Heritage

NOTES

- Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story—1965–2000 (Singapore: Times Editions, 2000).