Developing a Liveable & Sustainable Singapore

ETHOS Issue 19, Jul 2018

Thinking Past Limits

When Singapore gained independence in 1965, national survival was at stake. With a small land area of 581 km2 then and no natural resources, it was burdened with high unemployment and squalid urban conditions1 Today, Singapore ranks among the world’s most competitive economies.2 The city-state’s streets are safe. Singapore’s urban landscape is clean, lined with trees and flowering shrubs, and dotted by green spaces and well-manicured gardens. Over 90% of Singaporeans own their homes, with about 80% living in multi-ethnic public housing estates.3 These estates are served by transport links and amenities ranging from neighbourhood shopping malls to community centres, schools, sports complexes and hawker centres that provide cheap and good food in a sanitary environment. Unemployment rates are low at 2.2% in 2017. 4

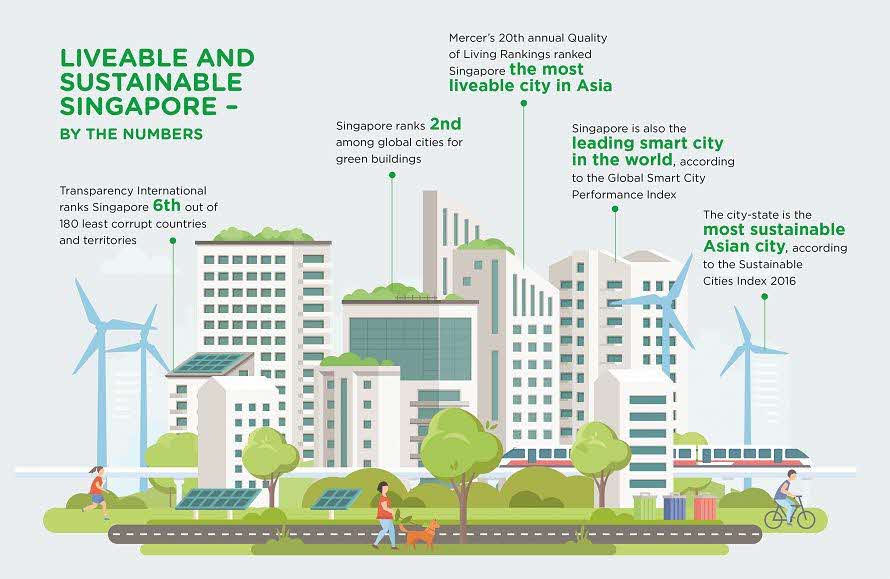

Liveable and Sustainable Singapore — By The Numbers

Sources:

- Lynette Khoo, “Singapore Ranks Top in Sustainability among Asian Cities, Second Globally”, The Business Times, 14 September 2016.

- Navin Sregantan, “Singapore Tops Global Smart City Performance Ranking in 2017: Study”, The Business Times, 14 March 2018.

- Navin Sregantan, “Singapore Still the Most Liveable City in Asia: Mercer”, The Business Times, 21 March 2018.

- Ng Huiwen, “Singapore Ranked 6th among 180 Countries in 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index”, The Straits Times, 22 February 2018.

- Nur Sabrina Azmi, “Singapore Ranks 2nd among Global Cities for Green Buildings”, The Business Times, 15 June 2016.

The disadvantages that Singapore faced as a city-state in its early days meant that its approach to planning and urban governance has had to be long-term, integrated, balanced and dynamic. For instance, while the immediate task upon independence was to create jobs and house the people, the need to curb pollution and diseases also meant that a “develop first, clean up later” model was not viable, given its small land area and lack of hinterland. Growth could not occur at the expense of the environment or citizens’ quality of life. Environmental protection therefore went hand in hand with the economic imperative—a good, clean and green environment made a positive impression on visitors and potential foreign investors. It differentiated Singapore from the other cities in the region, and demonstrated exceptional, effective and efficient governance.

Good urban governance requires technocratic and professional expertise: it requires a capable public service, even as the political leadership sets the overall direction, based on the electorate’s aspirations and interests.

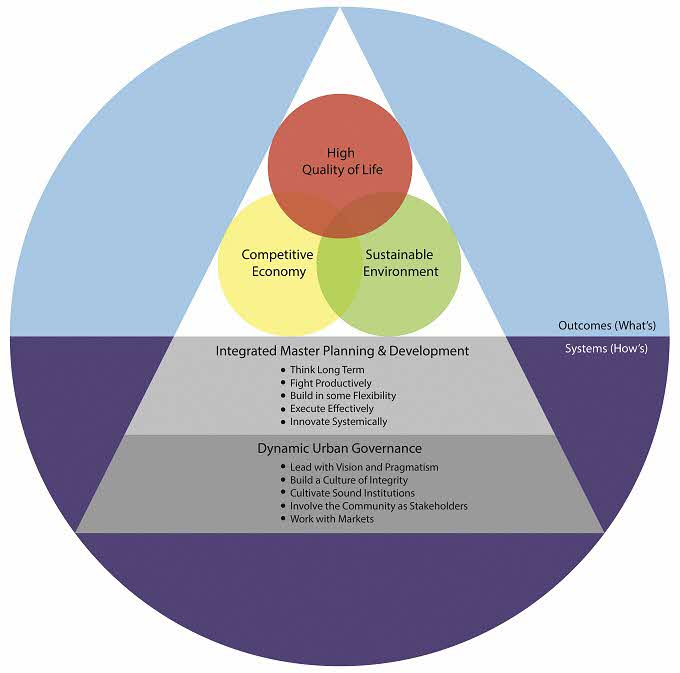

The CLC Liveability Framework

Good urban governance requires technocratic and professional expertise: it requires a capable public service, even as the political leadership sets the overall direction, based on the electorate’s aspirations and interests.1 The Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC), in researching Singapore’s urban planning and development achievements, has distilled a large body of codified and tacit knowledge and developed the CLC Liveability Framework. Ten implicit principles were identified and they form the two key pillars of the Framework—the Integrated Master Planning and Development system, and the Dynamic Urban Governance approach.2 These ten principles, taken together, account for three outcomes, namely: a competitive economy, a sustainable environment and a high quality of life.

Source: Centre for Liveable Cities

Integrated Master Planning and Development

Peter Ho, Chairman of the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), has observed that thinking long term made Singapore’s urban planners “adopt a future-oriented and long-term perspective in policy formulation. This avoids the pitfall of making decisions that might be expedient in the short term but prove costly later on.” To “fight productively” means making decisions that are derived from robust debates among all stakeholders, in order to find the strongest ideas for Singapore. Consensus is reached “not from fulfilling all the desires of all the stakeholders, but from finding compromises among all stakeholders”. The need to “build in some flexibility” has characterised Singapore’s urban planning regime, which has had to question assumptions and even reverse decisions if circumstances change in a volatile environment. “Execute effectively” and “innovate systematically” reflect the Singapore government’s proclivity towards action rather than “maintaining the status quo”: holding to the dictum that “policy is implementation, and implementation is policy”. Policy entrepreneurship, encouraged by the government, becomes a way to find new urban solutions that maximise the effectiveness of scarce national resources.3

Notes

- S. Dhanabalan, Interview by the Centre for Liveable Cities (unpublished transcript), 20 December 2011.

- Khoo Teng Chye, “The CLC Liveability Framework”, Liveable & Sustainable Cities: A Framework (Singapore: Centre for Liveable Cities and Civil Service College, 2014), 2–42.

- Peter Ho, “Epilogue”, Liveable & Sustainable Cities, 251–253.

Dynamic Urban Governance

Under the CLC Liveability Framework, five guiding principles stand out as key to Singapore’s dynamic urban governance approach:

Lead with Vision and Pragmatism

Singapore’s model of urban governance derives in part from the exigencies of a severely resource-challenged and economically vulnerable polity. As founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s candid assessment of Singapore’s prospects in 1965 suggests:

“[…] an island city-state in Southeast Asia could not be ordinary if it was to survive. We had to make extraordinary efforts to become a tightly knit, rugged and adaptable people who could do things better and cheaper than our neighbours, because they wanted to bypass us and render obsolete our role as the entrepôt and middleman for the trade of the region. We had to be different.” 5

This ethic has strongly informed the mindset of the core leadership in Singapore since. As a result, governance in the city-state has been characterised by the prioritisation of economic progress and socio-political harmony, regarded as a critical component of overall development.

Since it gained power in 1959, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has governed continuously for nearly six decades. Political longevity has allowed the government to adopt a long-term, futureoriented perspective to policymaking and urban planning, while responding to the needs of Singaporeans. As one former senior civil servant put it, “it is the practice of good politics that drives urban governance”6 in a virtuous cycle.

At the same time, Singapore could not afford the luxury of ideological approaches to governance: its policies had to work in practice, not just in theory, with the vulnerable young city-state’s survival at stake. An ethos of pursuing ideas that work on the ground, and of learning by doing while keeping broader visionary objectives in sight, have been a hallmark of public administration during Singapore’s early days.

We are pragmatists. We do not stick to any ideology. Does a policy work? Let us try it, and, if it does work, fine, let us continue with it. If it does not work, toss it out, try another one that may work.

—Lee Kuan Yew,

founding Prime Minister7

Build a Culture of Integrity8

Those responsible for city planning propose and develop many large infrastructure projects that shape the city, involving significant national resources. How well these officials do their work affects the day-to-day living of many citizens: from the roads used, to the roofs over their heads.

Public sector culture affects how civil servants and public officers, as well as politicians, carry out their responsibilities.

What has stood out in Singapore’s development experience is the emphasis on establishing a culture of integrity. In this respect, the Singapore Public Service has long been concerned with keeping itself honest. It maintains its reputation for incorruptibility with an extreme intolerance of corruption.

While holding public officers to a high standard of probity, the government also remunerates them with market-competitive salaries to reduce the temptation for graft. They must also avoid conflicts of interests between their official positions and private interests; refuse, surrender or declare and pay for gifts given in connection with their work; sign an annual declaration of non-indebtedness in order to avoid acquiring compromising obligations; and declare their personal and familial assets to make transparent any properties or investments acquired beyond their means.

Was it planned from the beginning? No! It was a process of learning, adjusting, refining and passing it on to the next generation so that they don’t have to relearn the process.

—Lee Kuan Yew9

Cultivate Sound Institutions

Honest, competent and motivated people

Although good leadership is key to a country’s or organisation’s success, decisions cannot be made on judgement and inevitable biases. Robust institutions and processes are important to ensure that all available resources and expertise within a country or organisation can be fully utilised.10

Since independence, the Singapore Government has regarded the public service as crucial to the achievement of its objectives. Transforming the colonial-era bureaucracy to a Singapore Public Service geared for nation-building involved the fostering of both human capital and institutions. Efficient and resilient institutions resulting in a capable technocracy has been central to the city-state’s rapid development.11

The close working relationship between the Singapore Public Service and the political leadership is seen as a means of encouraging effective and efficient implementation of policies and programmes.12 The centrality of the public service to the government’s development objectives for the country, and the need for talented officers to carry out those objectives, have led the government to pursue aggressive talent recruitment, development, and retention policies for the public service. Meritocracy informs the recruitment and promotion of public servants at all levels. The Public Service Commission and other public agencies in Singapore award scholarships for tertiary education to academically able students who are then bonded to serve their sponsoring agencies for a period of time. Emphasis is also placed on fostering morale, promoting staff well-being, and encouraging consistent training and continuous learning.13

Agile, innovative agencies

While the limits of resources, whether natural, physical or financial, place bounds on urban development, innovation can mitigate these limits or remove them in the long term. Innovative thinking, coupled with engineering expertise, have been vital in ensuring that urban policies and programmes make Singapore’s 721.5 km2 of land area liveable.14 Solving Singapore’s urban problems required officials to see different possibilities beyond conventional wisdom. It was this audacity that led Singapore to court investment from multinational corporations to generate export-led economic growth when it was unfashionable thinking to do so in the 1960s. It also introduced the world’s first road usage pricing system in 1975 to ease traffic congestion, which was ahead of its time, though common place now.15

The priority given to housing and economic development was clear from the fact that the first statutory boards created under self-government were the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in 1960, to construct public housing for Singaporeans, and the Economic Development Board (EDB) in 1961, to attract job-creating direct investments to Singapore. With more autonomy than ministries in implementing public policy and pursuing innovations in their specific areas of focus, these statutory boards have outperformed their predecessor organisations (such as the Singapore Improvement Trust and the Singapore Industrial Promotion Board respectively). Other specialised public agencies include the Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) to develop and manage industrial estates, and the Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) to provide industrial capital.

Involve the Community as Stakeholders

Since the 1960s, a number of campaigns have been launched to inculcate a sense of civic ownership. These include the 1967 “Garden City” campaign, the 1968 “Keep Singapore Clean” campaign, the 1971 tree planting campaign and Annual Save Water Campaigns, and so on. More recent programmes, such as the Community Gardening initiative, the 1997 “Adopt a Park” and the 2006 “Friends of Water”, encourage the community to get involved in taking care of the environment and natural resources.

On the planning front, the Concept Plans and Master Plans of the Ministry of National Development (MND) have been open to public consultation since the 1980s. Development plans and guidelines are published and widely disseminated to developers, professionals and the public through the media, government gazette, dialogue sessions and public exhibitions, and feedback is solicited. In recent times, beyond a more straightforward public consultation, officials have taken steps to more actively canvass for ideas from the public. Recognising that an empowered citizenry participating in the policymaking process—and taking shared ownership over public outcomes—is essential for public policy success, public engagement has become an integral part of urban governance processes. In recent years, these efforts have also involved the judicious use of digital platforms to actively encourage citizen participation and engagement.16

Public engagement efforts have also been accompanied by a Public Service Transformation (PST) push in August 2012. This marked “a shift from a transactional mode of governance to a more relational one”. With the aim of building “One Trusted Public Service with Citizens at the Centre”, PST sought to create a more empathetic and citizencentric Public Service. The then Head of Civil Service, Peter Ong, laid out the tasks ahead for the Public Service: “to partner Singaporeans and harness their energies and ideas for the good of Singapore. No one has the monopoly on ideas and the public service may not always have the answer, or be the answer. We are constantly on the lookout for opportunities to crowdsource, consult and co-create—both within the service and with Singaporeans—as we shape our future together”.17

Work with Markets

A driving force behind Singapore’s urban governance approach has been the consistent emphasis on improving the efficiency of public service delivery by leveraging market forces as much as possible while avoiding the pitfalls of market failure.

This requires careful balancing between the competing demands of a diverse stakeholder community. While the government can level the playing field and provide an environment for entrepreneurs to earn decent profits, it also has to enforce regulations on businesses to ensure that the costs of externalities are not unfairly borne by society, that there is sufficient competition in the marketplace to protect the interests of consumers, and that appropriate interventions are made where the market has failed—to ensure that public interest is upheld.

Public housing is one example where the government has applied market principles to ensure effective public service delivery. Public housing is subsidised through the mechanism of pricing flats below market value to promote the social goal of home ownership, thereby increasing the sense of belonging to Singapore; and ensuring the affordability of public housing. New flat buyers pay different market prices which are determined by the location, floor level, orientation, design and size of their properties. This market subsidy approach is more equitable for flat buyers as it recognises the variable market values of individual properties.18

Singapore’s water policies also benefit from the application of market principles, namely: not subsidising water consumption, pricing water to reflect its true value and working with the private sector to exploit technology to produce alternative sources of potable water in a cost-effective manner. Thus, even though Singapore is one of the most water-stressed places in the world, it continues to maintain access to adequate supplies of potable water. This is the result of consistent investments in water treatment and reclamation technologies and infrastructure, appropriately scaled to make water affordable but without subsidising consumption and encouraging a culture of prudent water use.19

On its own, the free market will worsen inequalities. [W]e believe in free markets but active government intervention where markets fail, together with personal responsibility and a supportive community.

—Desmond Lee,

Second Minister for National Development20

Governing for the Future

When Singapore was thrust into independence, there was little inkling of what the future might hold. The foremost need was to make this small new island nation work and thrive. It was a time for action rather than reflection. There was no room to systematically formulate and codify principles of governance. It is only later, with a proven track record of success, that Singapore’s public sector sought to document our experiences and hard-won lessons, and to codify the principles that have guided Singapore’s integrated planning and development and approach to dynamic urban governance. Our current landscape is one of a more diverse population, in which the interests of a complex network of stakeholders intersect, cross-cut or even compete. At the same time, we need to engage with a rapidly changing world where international rules that have provided stability since World War Two are being stress-tested or disrupted. In this context, a framework of principles for governance offers an anchor for us to frame, understand and approach change. But circumstances evolve, and new developments, including the technological and social, are overturning existing models of doing things. Our approaches to nation-building must continue to evolve with the shifting political and economic landscape, even as we adhere to the core values of integrity, service and excellence that ground and guide us in a volatile world.

- W.G. Huff, The Economic Growth of Singapore: Trade and Development in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 291.

- Singapore was ranked number two in the World Bank’s Doing Business 2018 report for the period to June 2017, see World Bank Group, “Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs”, accessed 22 December 2017, http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings. Singapore was also ranked the third most competitive country in the world in the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook 2017, see International Institute for Management Development, “IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook 2017 Results”, accessed 22 December 2017, https://www.imd.org/centers/world-competitiveness-center/rankings/.

- Department of Statistics, Singapore, “Home Ownership Rate” and “Resident Households by Type of Dwelling”, accessed 13 June 2018, https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/households/households/latest-data.

- See Ministry of Manpower, Singapore, “Summary Table: Unemployment”, accessed 17 April 2018, http://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Unemployment-Summary-Table.aspx.

- Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965–2000 (Singapore: Times Media and The Straits Times Press, 2000), 24.

- Ngiam Tong Dow, “The Politics Behind Development Policies”, The Straits Times, 19 November 2011.

- Cecilia Tortajada and Asit K. Biswas, “What made Singapore tick: Soft options and hard rules”, The Straits Times, 31 December 2017.

- For an account of Singapore’s successful transformation from a corruption ridden society to a clean country with low levels of corruption, see Eddie Choo, Cindy Tan and Toh Boon Kwan, Upholding Integrity in the Public Service (Singapore: Civil Service College, 2015).

- Sunanda K. Datta-Ray, Looking East to Look West: Lee Kuan Yew’s Mission India (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009), 134.

- Lim Hng Kiang, Interview by the Centre for Liveable Cities (unpublished transcript), 13 April 2012.

- See Michael Barr, “Beyond Technocracy: The Culture of Elite Governance in Lee Hsien Loong’s Singapore”, Asian Studies Review, 30, 1, March 2006, 1-17; and Gary Rodan and Kanishka Jayasuriya, “The Technocratic Politics of Administrative Participation: Case Studies of Singapore and Vietnam”, Democratization, 14, 5, December 2007, 795-815. The Economist referred to Singapore as “the best advertisement for technocracy”. See “Minds Like Machines”, The Economist, 19 November 2011.

- See Han Fook Kwang, Warren Fernandez and Sumiko Tan, eds., Lee Kuan Yew: The Man and His Ideas (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1998), 92; Neo Boon Siong and Geraldine Chen, Dynamic Governance: Embedding Culture, Capabilities and Change in Singapore (Singapore: World Scientific, 2007), 323.

- For more information on the Singapore Public Service’s talent recruitment, development and retention efforts, see Neo and Chen, Dynamic Governance, chapter 7.

- Singapore’s land area has increased since independence through land reclamation from the sea.

- See Singapore Infopedia, “Area Licensing Scheme”, accessed 13 June 2018, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_777_2004-12-13.html.

- For example, the Municipal Services Office’s OneService mobile application allows citizens to provide prompt feedback on municipal issues and makes it more convenient for them to access municipal services. The Land Transport Authority’s Beeline public transport application aggregates data on commuters’ transport needs and feed these to transport operators to consider providing a new service to plug the gap. The code for Beeline has been made open source since October 1, 2017 to further encourage community innovation.

- June Gwee, “Introduction,” in June Gwee, ed., Case Studies: Building Communities in Singapore (Singapore: Civil Service College, 2015), 2; Peter Ong, “Public service wants to crowdsource, consult and co-create”, The Straits Times, 5 November 2015.

- Mah Bow Tan, “Pricing Flats According to their Value”, Today, 29 October 2010, accessed 13 November 2015, https://www.mnd.gov.sg/home.

- Tan Gee Paw, Singapore Chronicles: Water (Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies and Straits Times Press, 2016), 10, 66, 80 and 86; Ng Joo Hee, “Waste to Potable Water—S’pore’s Solution to World’s Water Problems”, The Business Times, 22 March 2018.

- Desmond Lee, “Speech by 2M Desmond Lee at the 9th Session of the World Urban Forum”, 9 February 2018, accessed 6 April 2018, https://www.mnd.gov.sg/newsroom/speeches/view/speech-by-2m-desmond-lee-at-the-9th-session-of-the-world-urban-forum.