Connecting to the World: Singapore as a Hub Port

ETHOS Issue 19, Jul 2018

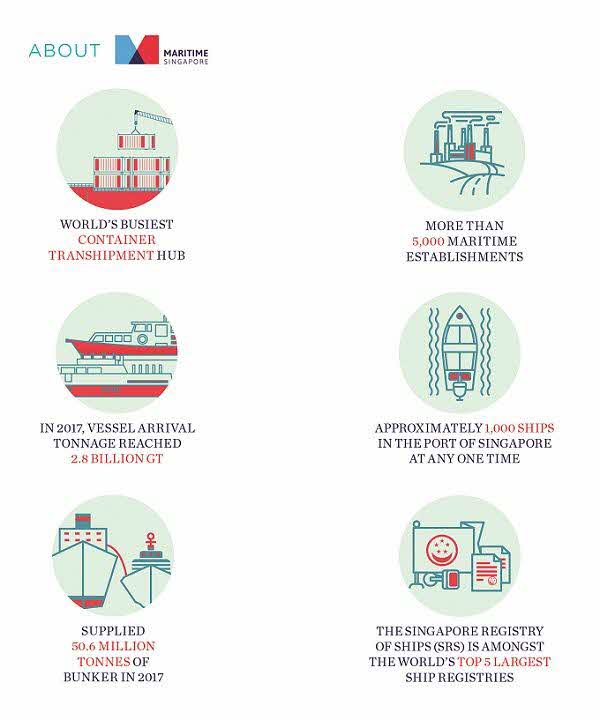

From its establishment as a British trading post in the early 19th century to its growth into a global transhipment hub, the development of Singapore’s port has been synonymous with the modern history of the island city-state, and the foresight exemplified by its leaders.

The decision taken in 1969 to build Singapore’s first container terminal in Tanjong Pagar propelled Singapore from a small port into the global league. Singapore was the first country in Southeast Asia with a container port, which has since grown to become one of the busiest and most connected in the world, with links to more than 600 ports across 120 countries worldwide. Annually, more than 130,000 ships call at Singapore.

While Singapore’s geographical location at the crossroads of important trade lines has been favourable, its pre-eminence as a global hub port has not been by chance. Strategic vision and leadership, with the courage to make bold decisions, have been vital in enabling Singapore to stay ready for the future, be a pacesetter, reap first-mover advantages, and thrive in a dynamic global industry.

Vision and Decisiveness: Staying ahead of the curve

In the 1960s, containerisation disrupted the shipping industry—much like how online shopping and third-party hailing apps disrupt the retail and taxi industries today. But the 1969 decision to build a container terminal in Singapore was a huge risk.

At that time, it was unclear whether there would be demand for container shipping along the Europe and Far East route that Singapore served. However, the alternative was an even bigger risk: becoming obsolete and irrelevant if container shipping were to become the prevailing mode of transporting cargo by sea.

Singapore’s first container terminal at Tanjong Pagar, which opened in 1972, allowed us to catch the wave of containerisation before the rest of the region. Had we waited for containerisation to take off before making the infrastructural investment, we would have lost this first-mover advantage.

Key Elements of a Successful Port

Singapore’s strategic vision for its port has been about ensuring the 3 Cs of Connectivity, Capacity, and Competitiveness.

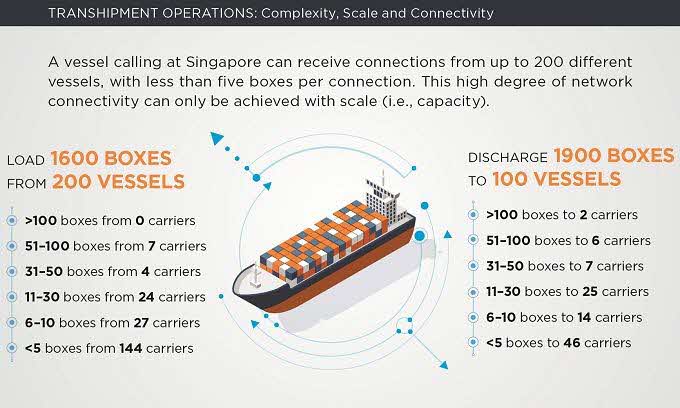

Connectivity is a measure of the frequency and range of feeder and deep-sea connections. Connectivity is key for shippers, and Singapore offers a high level of connectivity as the primary transhipment hub in the region. By anchoring key shipping lines and alliances that ply the main shipping route from Asia to Europe, and establishing a strong complementary feeder network to smaller ports in the region, Singapore has built up a reliable and densely connected network. We are able to handle increasingly fragmented and dispersed connections across shipping lines and feeders.

Long-term, strategic port planning must ensure that the port can provide adequate capacity to meet the demands of key shipping lines and their alliance partners in sizeable blocks of volume. This means being able to berth their vessels and conduct cargo operations efficiently. Scale, and the availability of space to grow the port, are essential for retaining Singapore’s edge in connectivity and network strength. Shipping lines prefer partnering with ports that can accommodate their long-term growth plans. Adequate port capacity and operational capability to keep pace with shipping lines’ demands provide certainty and distinguish Singapore’s port. Together with Singapore’s competitive advantage in connectivity, assurance of capacity goes a long way in helping PSA to ink new joint ventures1 with leading shipping lines and secure long-term commitments in Singapore.

Creating value for key stakeholders2 or bettering our business proposition (e.g., by leveraging technology to deliver more efficient service) is vital to sharpening competitiveness. Singapore’s value proposition is that of a “catch-up port” that offers shorter transit times and enables vessels to make up for delays upstream. Delivering efficient service in an optimum manner helps shipping lines reduce costs. To this end, Singapore has continually invested in technology and innovation to extract productivity gains and enhance our competitiveness.

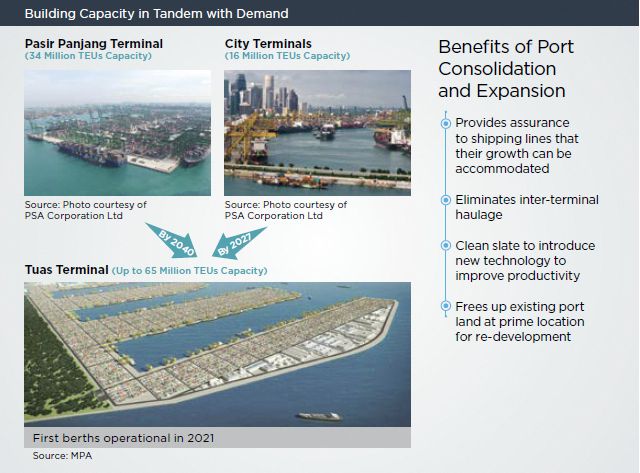

The decision to expand Pasir Panjang Terminal in 2004 provided the necessary capacity to cater to growth in container throughput.

With this, Singapore has been able to maintain its position as the world’s leading transhipment port. In addition, it has enabled Singapore to anchor global shipping lines such as China’s Cosco and France’s CMA CGM, both of which have joint-venture agreements with PSA to operate berths at Pasir Panjang Terminal.

New port cranes will allow for remote monitoring, supervision and control of up to 5 cranes.

Source: Photo courtesy of PSA Corporation Ltd

In addition, greater connectivity (i.e., more deep-sea and feeder connections from the port) enhances the product diversity that the port supports, adding value and improving competitiveness. By offering top-notch productivity and unrivalled connectivity on an unmatched scale, Singapore’s port has become a critical nexus in the global sea-trade system.3

In place of conventional railmounted gantry cranes that are individually manned, PSA has introduced new systems at Pasir Panjang Terminal that enable a single crane operator to remotely monitor and control the operations of up to five cranes.

By offering top-notch productivity and unrivalled connectivity on an unmatched scale, Singapore’s port has become a critical nexus in the global sea-trade system.

Shipping Landscape Today

An increase in scale

Shipping alliances today have become larger as shipping lines consolidate. Shipping lines are deploying mega vessels4 (i.e., a vessel with a capacity in excess of 10,000 twenty-foot equivalent units, or TEUs) on major trade routes. Underpinning these trends is the industry’s belief that size and scale are prerequisites for survival, and that smaller players will be hardpressed to out-price larger alliances. The increasing use of mega vessels and consolidation of shipping lines into ever larger alliances will accentuate peak volumes and increase the complexity of transhipment operations. An analogy would be a big group of diners showing up at a restaurant at the same time and demanding to be seated together. Consequently, a transhipment hub’s ability to accommodate larger alliances and their more complex transhipment connections will be critical to its success or survival. Ports that fail to invest in capacity in anticipation of demand will find it challenging to deliver the high service levels that have come to be expected.

Digital revolution

Digital developments are poised to transform the entire global maritime industry, including the port. PSA invests in technology as a multiplier of capacity, to boost productivity and improve port operations. Aided by technology, advanced planning and optimisation of equipment deployment will facilitate the seamless transfer of containers from vessel to wharf, and then to truck and yard, and vice versa. Harnessing automation will also increase PSA’s competitiveness. For instance, instead of prime mover drivers, automated guided vehicles (AGVs) will ferry container boxes around our port at the new Tuas Terminal.

For Singapore to stay ahead of the curve, flexibility and open-mindedness in enacting business-friendly regulations and experimenting with new ideas and technologies are essential. For instance, the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) proactively experiments with digitalisation initiatives, adopting a “regulatory sandbox” approach in which trials with new technologies may be observed in controlled environments. This enables regulators to be up-to-speed when introducing new regulations and capturing first mover advantages. PSA and MPA have also established living labs to facilitate the test-bedding of new technologies, with a view to future large scale deployment at Tuas. These initiatives will help promote cutting-edge innovation and build up competencies in port development.

The Broader Economic Importance of Singapore’s Port

Singapore is committed to sustaining the growth of our port because this is an industry critical to our economy.

Our leading position as an International Maritime Centre (IMC) is built upon our status as a top transhipment hub. Strong linkages and a high degree of complementarity between the port and the IMC mean that the port is the driving force behind Singapore’s vibrant maritime sector and economy at large—it anchors shipping lines in Singapore. Once shipping groups establish operations in Singapore, there is a stronger impetus to shift their other functions and activities to Singapore too. By encouraging greater “stickiness” of shipping groups, the port has helped draw in other international maritime companies providing essential services to support the shipping lines. In turn, this has helped spawn a wider ecosystem of maritime service providers including bunkering, shipbroking, ship finance, martime insurance, as well as maritime law and arbitration, amongst others.

Project SAFER

Given the need to ensure navigational safety as Singapore’s vessel traffic grows, Project SAFER is a collaboration between MPA and IBM Research to develop and test-bed new analytics-based technologies to improve maritime and port operations.

The SAFER system can automate and increase the accuracy of critical tasks that formerly replied on human observation, reporting, Very High Frequency (VHF) reporting and data entry.

Examples include Automated Movement Detection and Utilisation Prediction.

Beyond the maritime sector, the port also supports other industries. Our position as a leading transhipment hub and well-connected port anchors the growth of Singapore’s logistics, manufacturing and wholesale trade sectors. As a hub port, Singapore is able to offer a high degree of connectivity and competitive shipping rates to an extensive range of players across the logistics supply chain. Superior maritime connectivity supports the manufacturing sector by contributing to the ease and affordability of importing raw goods and exporting manufactured products. Access to the connectivity afforded by our port is a critical consideration in wholesale trade and logistics companies’ decisions to be located in Singapore. Today, we see global shipping and logistics players tapping on Singapore as a base for regional operations.

The twin pillars of Maritime Singapore—our hub port and IMC—account for the lion’s share of Maritime Singapore’s 7% contribution to GDP and employ more than 170,000 people in Singapore. The port, in particular, is a source of good jobs for locals—the percentage of locals employed by the port sector is consistently higher than the national average. The percentage of locals in the port sector holding PMET (Professionals, Managers, Executives and Technicians) positions also far outstrips the national average.

Anchoring Maersk to Singapore

The port played a significant role in anchoring the Maersk Group’s shipping and related services in Singapore. Maersk started out using Singapore as its transhipment hub, subsequently expanded the breadth of its operations in Singapore, and eventually established its regional headquarters here. Today, Singapore is the Maersk Group’s largest business operations centre outside Denmark, with about 650 employees. It performs global and regional functions for 13 business units that span the container, drilling, tanker, towage and salvage, and terminals business segments. Besides the port, the conducive business framework environment in Singapore is a key factor which contributes to its growth.

Looking Ahead to Tuas

By the early 1980s, it was apparent that Singapore’s first container terminal, Tanjong Pagar Terminal, would be operating at maximum capacity by the 1990s and would not be able to handle the envisaged growth in trade volumes. Beyond the City Terminals (Tanjong Pagar, Brani, and Keppel Terminals), plans were made for port expansion at Pasir Panjang. By 2000, Singapore’s container throughput had reached 17.1 million TEUs. City planners were already looking ahead to the relocation of the container port as the next chapter in Singapore’s maritime story. The decision to consolidate the port at Tuas with a planned capacity of up to 65 million TEUs was made with an eye on the future. Having sufficient capacity in a single, contiguous location affords Singapore a critical competitive advantage—it provides greater economies of scale and also eliminates the need for inter-terminal haulage. In addition, the certainty of increased capacity at Tuas provides assurance to shipping lines and alliances that Singapore can accommodate their growth over the long term. This helps position Singapore’s port more competitively amidst increased competition.

GOSHO—world’s largest grab dredger currently deployed at Tuas for reclamation works

Source: MPA

Tuas Terminal is expected to be the largest container terminal in the world in a single location. It is designed with finger-shaped piers to yield higher capacity berths by maximising usable berth length and enhancing utilisation intensity. Beyond berth design, the construction of Tuas Terminal is also record-breaking in several aspects. For example, each of the caissons that form the permanent wharf structure is 28 metres tall (about 10 storeys high) and weighs the equivalent of around 8,000 cars—these caissons designed for the first phase of Tuas Terminal are amongst the largest ever used in the world. In addition, the world’s largest grab dredger, the GOSHO, has also been mobilised for reclamation works—it can fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool with just 15 grabs!

Unlike other ports that are completely out of bounds to the public, Tuas will incorporate elements of community integration.

Productivity improvements in port operations are also critical to meet demandside requirements (e.g., catering to mega vessels) and address Singapore’s perennial supply-side constraints (i.e., land and labour scarcity). Notably, large-scale deployment of AGVs as well as automated yard and quay cranes at Tuas Terminal, all of which would be remotely operated from a control centre, will improve port productivity.

PSA continues to harness data and technology to optimise turnaround times and facilitate just-in-time port calls, with a view to sustaining high berth and yard productivity. Today, PSA is already achieving higher and consistent berth productivity through intelligent planning and automation. PSA works with key customers to develop protocols for vessel stowage (placement of containers on vessels) to facilitate optimal container loading and discharging rates. Last but not least, PSA has also been actively working with planners of shipping lines to spread out cargo volumes such that more cranes can be deployed to minimise each vessels’ turnaround time.

Given the scale and complexity of Tuas Terminal, the Next Generation Port 2030 (NGP 2030) Initiative is a multiagency effort led by MPA to create an intelligent and sustainable port at Tuas through improving space utilisation, land-use, productivity and efficiency. Unlike other ports that are completely out of bounds to the public, Tuas will incorporate elements of community integration. The Tuas Terminal gateway, which will be the interface between areas inside and outside the port, will be a multi-purpose complex with offices and even a maritime-themed visitors’ gallery. Agencies are also working together to ensure accessibility for port workers to and from home to work.

Conclusion

Beyond our natural attributes, Singapore’s development into a global hub port within our first 50 years of nationhood is no accident. The unparalleled scale and connectivity that we have assiduously cultivated, underpinned by solid operational capabilities, have enabled us to deliver compelling value to shipping lines. Forward-looking leadership, coupled with the courage to take bold decisions, will enable Singapore to continue capitalising on its hard-won advantages in this era of globalised competition between major hub ports to attract transhipment business.

NOTES

- For instance, PSA signed a joint venture agreement with CMA-CGM in 2016, while Cosco expanded its Singapore joint venture with PSA in 2017.

- Key stakeholders include shipping lines, cargo owners, and freight forwarders.

- The 2014 OECD report “The Competitiveness of Global Port-Cities” cited Singapore as the number one port in the world according to its three measures of “centrality” within the global sea-trade network.

- The largest mega vessel today is the OOCL Hong Kong with a capacity of over 21,000 TEUs. Shipping lines have placed orders for 22,000 TEU containerships.