Project Tap out: Nudging Commuter Habits with Behavioural Insights

ETHOS Issue 17 June 2017

To the vast majority of public transport commuters in Singapore, “tapping out” their travel cards when exiting a public bus has become an ingrained habit: they do so to avoid the penalty of having the maximum route fare charged to their travel cards. However, more than half of commuters who hold Monthly Concession Passes (MCP) do not do so. Since MCP holders pay a flat fee for unlimited travel on public transport for a fixed period of time, they do not see the need to tap out, nor are they subject to the maximum fare penalty that regular commuters face if they skip this step when exiting the bus.

From an administrative perspective, tapping out contributes to data on commuter travel patterns, which is needed to plan bus routes and compute bus loads in real-time. In the absence of tap-out data to indicate the distance travelled, the public transport operators (PTOs) that run our buses have to charge the maximum possible fare, for which (in the case of MCPS, which are a form of subsidised public transport) they are reimbursed by the government. In other words, a failure to tap out may use more public funds than warranted by the travel actually consumed by MCP holders. If travel concession schemes were to be extended to more segments of the population, this problem could well be exacerbated.

Why Apply Behavioural Insights?

One obvious solution might be to impose a full trip fare on MCP holders who do not tap out: a penalty which has been effective for regular bus commuters. However, as MCP holders already pay for their monthly pass upfront, they may feel that this penalty is unfair. Furthermore, they would need to have an additional “purse value” in their travel cards to be charged the penalty, which could leave those with an insufficient purse value (including younger students) stranded. To modify the entire MCP system to include a penalty would also have required significant investments in time and money. Given these considerations, the Land Transport Authority (LTA) and the Civil Service College (CSC) worked together to run a randomised controlled trial, to explore behavioural nudges that might encourage MCP holders to tap out.

Defining the Problem

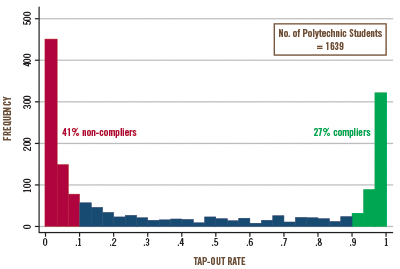

Available travel data showed that polytechnic students had one of the lowest tap-out rates among all MCP holders; it also revealed specific bus routes which ran along or terminated in and around polytechnics had particularly high non tap-out rates, where 41% of polytechnic MCP holders hardly tapped out at all (less than 10% of the time) (see Figure 1). Based on this information, the trial focused exclusively on changing the tap-out behaviour of polytechnic students who were defined as “non-compliers” in this experiment, i.e., those who tapped out less than 10% of the time; this allowed it to be run on a manageable scale, and to provide more insights to potential nudges that would change habits.

Source: Land Transport Authority, data from 20 October 2014 to 12 December 2014 and from 5 January 2015 to 6 February 2015.

Figure 1: Tap-Out Rate Distribution for Polytechnic Students Using Monthly Concession Pass

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to understand commuter attitudes and tap-out behaviour. Focus group discussions highlighted that one of the key reasons underlying current behaviour was peer influence (“My friends told me there was no need to do so”). Others felt that tapping out was inconvenient. However, the focus groups also revealed that students seemed to respond positively to tapping out when they were given a simple reason to do so, e.g. to help the government plan bus services better. This was in contrast to more technical reasons typically cited within policy circles, such as potentially passing on costs to regular commuters — such complex reasoning was lost on students and did not seem useful as a nudge (see box story).

Simple Message: “It is important that you tap out when alighting from buses even if, as a monthly concession pass holder, you might feel it makes no difference to you. This is because by tapping out, you give the government more accurate information about your bus journeys and how crowded buses truly are. With this information, the government can do a better job of improving bus services across Singapore.”

Complex Message: “I already enjoy a subsidy when I travel on a monthly concession pass. If I do not tap out whenever I take the bus, other public transport users / the government may have to further cross-subsidise my bus fares. This is unfair to other public transport users.”

Running the Randomised Controlled Trial

Polytechnic students were recruited for the experiment through email invitations, with a promise of at least $30 for full participation. To be shortlisted, they had to be regular bus users (at least 10 trips per week) with a low pre-experiment tap-out rate of at most 10%. A total of 453 students were chosen out of an initial 1,986 who registered, and randomly assigned into one of the five groups.

The final trial, which lasted eight weeks from April to June 2015, consisted of one control group of 50 students and four treatment arms of about 100 each.

Students in the Control group were included to account for the effect of being in an experiment, where behaviour might change simply because one is being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect). This group provided baseline data with which to compare the behaviour of students from the intervention groups.

Participants in the Information-only group were told why tapping out is important but not given any monetary incentive.

Three Information + monetary incentive groups were also formed, consisting of participants who were given the same information as the information-only group, in addition to being:

Gain group: paid a bonus for tapping out (bonus of 20 cents every time they tapped out, up to $4 for every two-week period);

Loss group: charged a penalty for not tapping out (the penalty of 20 cents every time they did not tap out was deducted from $4 that was given to each student for every two-week period);

Lottery group: entered into a lottery if they tapped out at least 20 times during every two-week period.1

All groups were sent fortnightly emails. Those in the Gain, Lottery and Loss groups had updates on their tap-out behaviour and the incentives/lottery outcomes, while emails to the Information group merely reiterated the reason for tapping out.

Results from the Trial

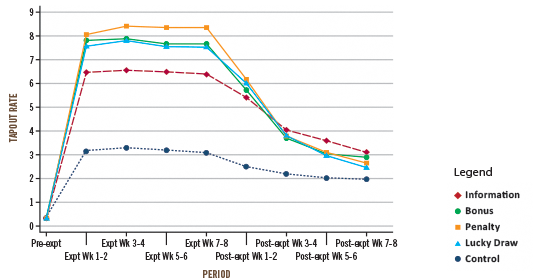

Within the first two weeks of the trial, tap-out rates rose quickly before remaining stable throughout the experiment. The Loss group, who incurred penalties for not tapping out, yielded the greatest improvement in tap-out rates. This increase in tap-out rates was statistically significant when compared to the Information group, but not for the Gain and Lottery groups. This is not surprising, since behavioural theory tells us that people tend to value losses more than gains of the same value (also known as “loss aversion”).

One unexpected but strong effect that was uncovered by the trial was that simply providing information alone resulted in a significant increase of 36% points in tap-outs and 29% points in compliance (defined as tapping out at least 90% of the time), when compared to the control group. Subsequent focus groups highlighted that this could be because tapping out was not too onerous, once they were given a reason to do so.

Did the Nudges Change Habits?

After the RCT ended, all incentives, penalties and information message prompts were ceased. All participants consequently tapped out less, although they were still tapping out more often than before the experiments.

Across participants, the tap-out rates of those exposed to monetary incentives fell at a faster rate than the information-only group. Six weeks after the trial ended, the tap-out rate and proportion of compliers from the information group were higher than the monetary intervention groups, and significantly so for the proportion of compliers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Tap-Out Rates of Participants Over Time

This suggests that any additional effect of monetary interventions during the experiment was lost once the interventions ended. While it is not possible to pinpoint the key reason, it is possible that the information-only nudge led to intrinsically motivated behaviour, which had a more sustained impact on tap-out behaviour compared to extrinsic (e.g. monetary) incentives. The post-trial results further suggest that extrinsic motivations ended up crowding out intrinsic motivations to tap out.

Conclusion

As a result of this study, between January and March 2017, LTA and the PTOs rolled out new “Tap Out for Better Services” information posters across the entire Singapore bus network and at bus stops outside polytechnics, universities and Institutes of Technical Education. Early indications are encouraging, with the overall non tap-out rate among polytechnic MCP holders falling from about 62% at the end of January to about 50% as of end April 2017.

The Project Tap-Out trial highlights the importance of testing to understand how different interventions play out on the ground, and how sustainable they are. In this context, providing information alone was effective and more sustained than monetary incentives. More importantly, the trial offered evidence on the unintended consequences of crowding out intrinsic motivations, when extrinsic rewards or penalties are introduced to encourage socially desirable behaviours. This is an important consideration for future policies, especially if monetary measures are not intended to be permanent. Insights from this and other such trials could help identify similar policy challenges, and explore ways to use information and data more effectively.

NOTES

- The prize was the value of a Hybrid Monthly Concession Pass ($51). There were eight winners per draw. Expected value of prize = 8 winners / 100 participants × $51 = $4.08 ≈ $4 maximum incentive for gain/loss.