‘Nudging’ Singapore to be Cleaner and Greener

ETHOS Issue 17 June 2017

The Need for Environmentally Friendly Behaviours

When people think of environmental issues, what often comes to mind are images of smoke-spewing chimneys, rubbish-strewn rivers and melting ice caps. For those living in countries with well-run municipal services, where pollutive activities are situated out of sight, environmental concerns can seem far removed from daily life.

This seems true of Singapore, where it can be less apparent that the accumulation of small daily actions and activities — such as not switching off the lights before leaving a room — can have significant negative environmental effects in the long run.

Individual action is not simply a good-to-have but essential part of the puzzle.

This indifference towards environmental issues is no trivial matter. Singapore is a small island state vulnerable to the challenges posed by climate change, including heightened competition for limited resources and potential supply disruptions due to extreme weather events. As the country increases in urban density, the need to manage the demands placed on our limited resources and infrastructure, and to mitigate the risk of environmental pollution will only increase.1 Individual Singaporeans cannot afford to remain passive actors in light of these environmental challenges.

Technological advancements may offer some solutions, but studies show that efficiency gains from technology (e.g. in energy-efficient appliances or water-saving devices) are often outpaced by consumption growth. More importantly, such advancements will only have an impact if there is broad behavioural change.2 For instance, a state-of-the-art recycling system will not be useful if people do not recycle their waste. In addressing environmental challenges, individual action is not simply a good-to-have, but an essential piece of the puzzle.

Why Traditional Policy Tools Do Not Always Work

The tools governments have traditionally used to improve environmental outcomes include economic instruments (price mechanisms, incentives and taxes); legislation; education and engagement programmes. Such tools work on the basis that individuals make optimal choices for themselves; however, if this were so, everyone would reduce their electricity consumption when prices are raised, stop littering to avoid fines, and start recycling after environmental campaigns!

The problem is that people do not make choices according to these assumptions. Most of the time, people simply rely on their choices being good enough or satisfactory — a decision-making strategy which Herbert Simon terms “satisficing”.3 Social influences also tempt us away from making environmentally friendly choices. Changing behaviours is therefore not a matter of simply invoking a system of external rewards or penalties.

Take for example the ubiquitous use of air-conditioning in Singapore: is it necessary for the temperature in offices and shopping malls to be set at such low levels? While raising the temperature by 1 to 2 degrees can help save on electricity bills and conserve energy without compromising on comfort, this is not often practised as decision-makers are often unaware of, or unable to assess, the potential benefits of doing so. Some business owners may even see risks in deviating from current air-conditioning norms and putting off tenants and patrons accustomed to cooler interiors.

Very often, even the simplest of behaviours — from separating recyclables from general waste or turning TV set-top boxes off — are hard to change. People tend to fall back on what is familiar or which requires the least time and effort, even when they might benefit from doing otherwise (e.g. in terms of cost savings or environmental benefits).4 In other cases, prevailing social norms hinder individuals from doing the ‘right’ thing. One of the reasons why issues of public cleanliness continue to persist even in Singapore is due to the fact that some people do not view small pieces of paper or cigarette butts as litter.5

Unless policy measures impose high costs or large benefits, they have limited impact on changing behaviour. Moreover, there are limits to the level of punishment that can be meted out for offences such as littering. Introducing new legislation to mandate environmentally friendly behaviours (e.g. recycling at home) might also be construed as overly intrusive, and there are practical limits to how much a government can police people’s behaviours.

Nudges fill the gap where traditional policy interventions have been found wanting.

‘Nudging’ People to be more Environmentally Friendly

In recent years, behavioural science interventions have demonstrated that people can be influenced to be more civic conscious without the need for expensive programmes or compulsion.6 Could such techniques, commonly known as ‘nudges’,7 complement existing policy initiatives to better achieve Singapore’s environmental goals?

Within the environmental context, nudges fill the gaps where traditional policy interventions have been found wanting on two accounts. Firstly, they offer an effective yet affordable and less intrusive way of getting people to adopt environmentally friendly behaviours. This is critical considering many of these behaviours are within the private sphere of people’s lives, in which excessive interference from the government is not desirable. Secondly, nudges directly address the social, cognitive and physical barriers — usually unaccounted for by traditional policy tools — that hinder such choices from being made in the first place. Nudges achieve this by making the right choices more apparent and accessible to those who are otherwise ill informed, do not care, or simply stuck in their ways.

Efforts to nudge people towards more environmentally friendly behaviours have generally involved (a) making the practical benefits of environmentally friendly options more salient, (b) leveraging social norms, and (c) making changes to the physical environment to reduce barriers.

Salience of Costs and Benefits

To overcome the general tendency for people to make decisions based on routines and ‘rule-of-thumb’ heuristics, environmentally friendly options need to be provided in a salient and timely manner to capture their attention. A common example, used in many countries, is eco-labelling.

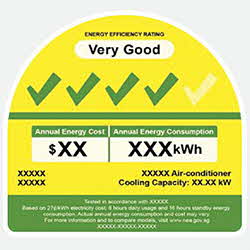

In Singapore, it is mandatory for suppliers to affix energy labels on air-conditioners, refrigerators, clothes dryers, televisions and lamps sold locally.

|

|

| Figure 1. Energy Label for Air-Conditioners, Refrigerators, Clothes Dryers and Televisions (Credit: National Environment Agency) | Figure 2. Energy Label for Lamps (Credit: National Environment Agency) |

Information on the annual energy consumption and running cost is displayed together with a rating of the appliance’s energy efficiency (with the best rating being three ticks for lamps and five ticks for other appliances). This makes it easier for consumers to choose the “better” alternative when purchasing an appliance.

Another effort that uses similar principles is the recent Car-Lite parking trial conducted by Singapore’s Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR), and Land Transport Authority (LTA). The trial tested the use of different pricing mechanisms to increase the saliency of parking charges in influencing people to drive less to work (see box story on “Reducing Car Usage”).

Participation in the Growth Vouchers Programme (UK)

As part of the efforts to move towards a Car-Lite Singapore, MEWR and LTA embarked on a project to examine the effectiveness of usage-based pricing in reducing the rate at which their employees drive to work.

The current monthly season parking scheme (MSP) charges employees a monthly fixed price for unlimited access to the car park. Such an upfront irrecoverable cost could have reduced the saliency of the charges, causing a sunk cost effect, prompting people to drive to work more than they otherwise would since they had already paid for season parking.

To test out the alternative idea of a daily season parking scheme (DSP), the LTA introduced a flat daily fee for using the car park (employees are not charged on days that they do not drive to work) from August 2013. This was positioned as an alternative to the current MSP which gives a month of unlimited car park access with upfront payment directly deducted from the employee’s pay. A difference-in-differences analysis showed that the average monthly car park usage for those who converted to the DSP dropped significantly by about 4 days (from 16.5 days to 12.5 days per month) compared to those who remained on the monthly scheme. This conclusion remained unchanged even after accounting for seasonality and individual differences.

At MEWR Environment Building, a randomised controlled trial on the DSP scheme was conducted over two months from August to September 2015. Drivers were randomly assigned to three schemes: (i) a daily charge of $4 per day for car park use, i.e. the DSP; (ii) a daily rebate scheme, where a monthly fee of $80 is paid upfront, but a rebate of $4 is received for every working day that the car park is not used; and (iii) a control group retaining the status quo, i.e. monthly season parking scheme. The car park fees for all officers involved in the trial were effected via the payroll and staff were regularly prompted to check their pay-slips to track their car park charges or rebates.

Results from the MEWR trial showed that the DSP had no significant effect. On the other hand, the daily rebate scheme was effective in the first month, resulting in a 13% reduction in car park use. However, changes for the second month were not significant.

It was interesting to note that the DSP seemed to work better at LTA than at MEWR, despite no known differences between the profile of employees. This was possibly due to the ERP-like deduction of parking fees at the LTA car park gantry system upon exit. In contrast, parking costs and rebates at MEWR were only available through monthly payslips. This delayed feedback could have resulted in employees valuing the time flexibility and convenience of driving more than future money savings (i.e. present bias).

The permanence of the DSP scheme at LTA could also have led its officers to consider their long-term savings when making driving decisions. On the other hand, the temporary nature of the trial at MEWR may have resulted in employees assessing that changing their behaviour for two months would not be worthwhile.

Social Norms

Social norms come in two forms — societal expectations and rules that guide behaviour (injunctive norms), or simply behaviours that are prevalent in society (descriptive norms). Individuals tend to behave in accordance to what is commonly deemed as “right” or commonly done.

A well-known example of how social norms have been used to nudge people to be more environmentally friendly is the incorporation of social comparisons in utility bills. Indicating how one’s energy consumption compares to “efficient” neighbours, coupled with the use of injunctive norms (e.g. and

faces to indicate the household’s energy performance), have been shown to be effective in encouraging households to reduce their overall energy consumption.8 Less energy efficient households have been found to improve on their energy performance to match and conform to their “good” performing neighbours.

In Singapore, the use of social norms can also be found in posters reminding people to keep their surroundings clean, reinforcing what is socially expected of people when using public spaces. For example, a message like “Your Considerate Act Lights Up Someone’s Day” evokes positive emotions and leverages people’s proclivity to conform to what is socially expected. People are thus influenced to keep their surroundings clean.

Changes in the Physical Environment

Making changes to the physical environ-ment by disrupting people’s routines and by making “green” options more appealing can also work as a powerful nudge. Such changes encourage people to reconsider their choices and to adopt environmentally friendly behaviours.

A study in Copenhagen, for example, found that placing footsteps on the ground leading to rubbish bins helped reduce littering substantially.9 These footprints, given their prominence, work as visible reminders to disrupt a person’s habit of littering and point them to an accessible alternative.

In Singapore, an ongoing study is attempting to assess whether second-hand cigarette smoke along public thoroughfares could be reduced by specially designating areas for smoking. By providing viable alternative places specifically for smoking, it is hoped that such public spaces can be better enjoyed by all.

More than Common Sense: Designing “Nudges” for the Environment

While behavioural nudges may seem little more than common sense, it is important to frame the issues correctly and objectively understand why certain behaviours persist. Four key factors influence the practice of environmentally friendly behaviours:10

- Attitudes, such as a person’s beliefs and values;

- Context, such as social influences, infrastructure, policy initiatives, monetary costs and benefits;

- Personal capabilities, such as knowledge, skills, the availability of money and time required to perform such actions; and

- Habits or routines.

These factors interact with one another, and may vary in influence. For example, buying an energy efficient appliance, with its higher upfront cost, might be more strongly influenced by a person’s disposable income (personal capabilities). Whereas the practice of recycling is probably a result of one’s personal habits and the availability of recycling infrastructure (context).

It is important to identify each target behaviour and understand the relevant barriers to action. Nudge effects may vary among contexts or situations which appear similar.

In designing and implementing environmental nudges, it is important to identify each target behaviour and understand the relevant barriers to action (e.g. by using surveys, interviews, ethnographic methods or secondary research). Furthermore, it is also vital to track the results of behavioural interventions. Nudge effects may vary even among contexts or situations which appear similar. Nudging may also give rise to unintended side effects. For example, the heightened awareness that one’s appliances are efficient may inadvertently result in them being used more frequently than necessary, causing a rebound effect which reduces the effectiveness of the intervention.

Relying on common sense alone is not enough. A robust system of testing, adapting and evaluating is needed to ensure that nudges remain effective in addressing environmental challenges and needs over time.

Conclusion

There is certainly room for the use of nudges to sustain a cleaner and greener environment. Given the fundamental disconnect between our daily lives and environmental issues, it is all the more important to try new approaches to create and sustain an environmental consciousness amongst people.

However, nudges should not diminish people’s ability to choose how to act. Neither should they be seen as replacements for traditional policy tools.11 Many behavioural interventions have been effective in part because of existing social and economic conditions established by traditional policy tools. For example, the use of energy labels to encourage people to buy more efficient appliances works partly because energy costs are priced correctly such that they promote sustainable consumption. Similarly, social norming interventions such as anti-littering posters are effective due to the possibility of sanction for violating such norms, e.g. fines. In essence, nudges serve not to replace, but to complement traditional policy interventions in addressing cognitive biases and social barriers that hinder people’s willingness and ability to become more environmentally friendly.

NOTES

- Tan Yong Soon, Sustainable Development: Challenges and Opportunities, Ethos 7(January 2010): 81–8.

- Linda Steg and Charles Vlek, “Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 29(2009): 309–17.

- Herbet A. Simon, “Rational Choice and the Structure of the Environment,” Psychological Review 63(1956): 129.

- Alice Moseley and Gerry Stoker, “Encouraging Civic Behaviour: A Randomised Controlled Trial of Interventions to Influence Organ Donor Registration,” Political Studies Association Conference, Edinburgh, Vol. 29, 2010.

- National Environment Agency Singapore, “Towards a Cleaner Singapore: Sociological Study on Littering in Singapore,” 2009.

- David McDaid and Sherry Merkur, “To nudge, or not to nudge, that is the question,” Eurohealth 20(2014): 3–5.

- Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (Yale, CN: Yale University Press, 2008).

- The monthly fee is paid upfront, deducted directly from the employee’s payroll.

- Hunt Allcott, “Social Norms and Energy Conservation,” Journal of Public Economics 95(2011): 1082–95.

- Simon, “Green nudge: Nudging litter into the bin,” iNudgeyou: The Applied Behavioural Science Group, 16 February 2012, https://inudgeyou.com/en/green-nudge-nudging-litter-into-the-bin/.

- Paul C. Stern, “New environmental theories: toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour,” Journal of Social Issues 56(2000): 407–24.

- David McDaid and Sherry Merkur, “To nudge, or not to nudge, that is the question,” Eurohealth 20(2014): 3–5.