Data Science in Public Policy — The New Revolution?

ETHOS Issue 17 June 2017

The Data Science Revolution

Using data to make decisions is not new, but we have seen data produced at an unprecedented rate by the Internet and mobile technologies. Yet, the revolution in data science is not so much about “data” itself, but the rapid advances in statistical methods and software that allow huge amounts of data to be analysed and understood. Indeed, this data science revolution has caused many industries to relook their strategies and introduce new ways of generating business. Modern analytics has made its way into just about every field: from public health, policing, economics and sports to political campaigns.

Modern analytics has also improved the way in which public policies are designed and implemented. For example, public officers can acquire and analyse data in real time, and develop more evidence-based solutions. In addition, datafication1 — the ability to transform non-traditional information sources such as text, images, and transactional records into data — has given policymakers fresh insights into perennial issues.

However, when the ultimate goal is behavioural change, data science and behavioural insights (BI) need to go hand in hand. Predictive analytics and nudges can serve as two parts of a greater, more effective whole.2 For instance, data science can help identify or predict groups that face high, moderate, or low risks in particular contexts. Policymakers can then channel resources towards more hands-on and high-impact interventions (e.g. personal visits) to address the highest-risk cases. For moderate- and low-risk individuals, low-cost, low-touch nudges (such as SMSes or letter reminders) could be sufficient to keep them on the right track.

Data science tools such as real-time data, data visualisation, and machine learning are already bringing new ideas and approaches to policymaking. Used together with behavioural approaches, they could revolutionise the way policies are made.

When the ultimate goal is behavioural change, predictive analytics and nudges can serve as two parts of a greater, more effective whole.

Real-Time Data and Data Visualisation

Real-time data refers to data that is passed along to the end-user as quickly as it is gathered — it is not kept or stored. Global Positioning Systems (GPS) that show drivers traffic situations around them are an example of real-time data in popular use. With data visualisation, real-time data can help policymakers to see patterns, get a better grasp of what is happening on the ground, and make more timely and better-informed choices.

Recent examples — from resolving the MRT Circle Line disruption to peat fire management in Indonesia — demonstrate how real-time data and visualisation have revolutionised and accelerated the effective resolution of complex policy issues and the management of crises.

Real-time data can also complement traditional ways of analysing, presenting and evaluating data. It can prompt policymakers to rethink established ways of addressing problems.

For example, the Pulse of the Economy, an initiative by the Government Technology Agency of Singapore (GovTech) in collaboration with various government economic agencies, uses high-frequency big data to develop new indicators to “nowcast” the economy. It draws from varied non-traditional sources of data, from Ez-link taps on the rail system to electricity consumption information, and even JobsBank applications and social media sentiments, to “nowcast”caihong the economy. For example, the amount of electricity consumed in a particular district in Singapore, and the number of people alighting at bus stops in the district, can provide a timely indicator of how much economic activity is happening in that area. Government agencies can identify areas of growth and formulate strategies based on emerging data and patterns — which may have otherwise gone unnoticed.3

Solving the Circle Line Disruption Mystery

Between August and November 2016, Singapore’s MRT Circle Line was hit by a spate of mysterious disruptions, causing confusion and distress to thousands of commuters. Prior investigations by train operator SMRT and the Land Transport Authority (LTA) indicated the cause as some form of signal interference. This resulted in signal loss and triggered the emergency brake safety feature in some trains, causing them to stop along the tracks. However, the incidents seemed to occur at random, making it difficult for the investigation team to pinpoint the exact cause.

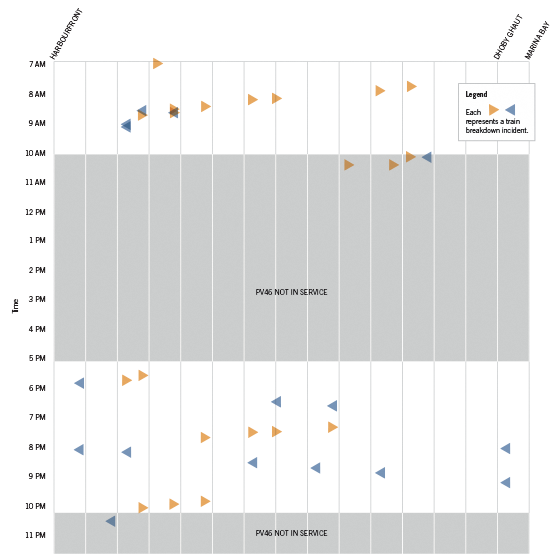

Using data including the date, time, location as well as train IDs from each incident, the Data Science team in the Government Technology Agency (GovTech) generated some exploratory visualisations. These showed that incidents were spread throughout each day, mirroring peak and off-peak travel times. Incidents happened at different locations on the Circle Line, with slightly more occurrences in the west. However, there were still no signs of where the signalling interruptions were coming from.

After train direction data was added to the chart, the team managed to pick up a pattern. They noticed the breakdowns seemed to happen in sequence. Once a train was hit by interference, another train behind it, moving in the same direction, was hit soon after, leaving a consecutive “trail of disaster” leading away from the initial incident. This raised the question of whether something that was not in the dataset had caused the incidents. Could the cause of the interference be a train going in the opposite direction?

Testing this hypothesis suggested that train disruptions could be linked to one “rogue” train, which itself might not be encountering any signalling issues. A review of video records of trains arriving at and leaving each station at the times of the incidents identified the suspect: PV46, a train that had been in service since 2015. When the team matched PV46’s location data to train disruptions, they concluded that more than 95% of all incidents from August to November 2016 could be attributed to this “rogue train”.1

Data visualisation helped GovTech officers pin down both the problem and the root cause of the train disruptions in a relatively short time.

Figure 1. Figure 1. Interference incidents during or around the time belt when PV46 was in service on 1 September 2016. Reproduced with permission from Government Technology Agency

NOTE

- The remaining incidents were likely to be due to signal loss, which happens occasionally under normal conditions.

Contributed by Data Science Division, Government Technology Agency

Supporting Forest and Peat Fire Management Using Social Media in Indonesia

Each year, forest and peatland fires spread across Kalimantan and Sumatra, mostly due to peatland drainage and the conversion of land to palm oil cultivation. Besides the damage caused to biodiversity and the ecosystems, according to UN Global Pulse, over 10 million people in Southeast Asia are affected by haze. Indonesian forest and peat fires in 1997 to 1998 were estimated to have caused over US$4.5 billion in damage, mostly health-related, across the region.1

To better support the Indonesian government in forest and peat fire management, the UN Pulse Lab Jakarta set up a baseline study of social media conversations on Twitter during and immediately after three fire-related haze events between 2011 and 2014. The study found that there were a larger number of relevant tweets during significant fire-related haze events. Topical analysis of over 4,000 tweets between the February to March 2014 haze event in Riau further revealed common patterns between tweets and hotspots during a fire event. The most frequently discussed topics were “Status of forest fires” (close to 1,200 tweets), followed by “Support from Government”, “Hotspot status” and “Support from Community” (in the range of 400 to 600 tweets).

As more Indonesians use social media during fire-related events, there is great potential for social media data to offer real-time insights related to public concerns and conversations. Twitter analysis, combined with other real-time data sources — such as remote sensing, mobile phone calls to emergency phone numbers or mobility traces — can also provide additional insights on disaster impact and recovery on the ground. Twitter can also be used to verify information channels or serve as an early warning mechanism for improved emergency response and management.

NOTE

- UN Global Pulse, “Feasibility Study: Supporting Forest and Peat Fire Management Using Social Media”, Global Pulse Project Series, No. 10, 2014, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/, accessed 3 January 2017.

Machine Learning

Machine learning, a branch of artificial intelligence (AI),4 is a statistical process that starts with a body of data and tries to derive a rule that explains the data or can predict future data. Unlike older AI systems where human experts determine the rules and criteria for the system to make analytical decisions, machine learning can be used even where it is difficult or not feasible to write down explicit rules to solve a problem.

Machine learning is already an essential feature of many commercial services such as trip planning, shopping recommendation system, and online ad targeting. It has also been applied in strategic games, language translation, self-driving vehicle, and even public services. In the public sector, machine learning software has helped the US Military to predict medical complications and improve treatment of severe combat wounds,5 and cities to schedule, track and provide just-in-time access to public transport.6 In Singapore, the Housing Development Board (HDB) in collaboration with GovTech used machine learning to identify customer concerns more accurately and adapt its policies to cater to citizens’ needs.

Building on the success of the HDB project, GovTech developed a text analysis platform, “GovText”,7 to enable public officers to apply unsupervised machine learning to discover topic clusters from textual data without any coding knowledge. GovText not only scales data science capabilities across all levels within the whole of government but also allows officers to improve their “ground-sensing” methods.

Making Sense of Public Feedback to the Housing Development Board (HDB)

The HDB’s Estate Administration & Property Group (EAPG) receives approximately 100,000 emails each year about flat sales. Together with GovTech, EAPG applied unsupervised machine learning to emails received in 2015 to discover key topics of public concerns. The analyses found about a cluster of emails on key collection: many new flat owners were emailing HDB to rush or delay their key collection date.

With this insight, HDB implemented an online system to schedule key collection, addressing the issue for both the public and HDB officers. This data-driven approach also helped improve the public sector’s “ground-sensing” ability, by surfacing emerging trends and issues that may not have been obvious before.

Contributed by Data Science Division, Government Technology Agency

The Predictive Power of Machine Learning

The bigger draw of machine learning lies in its predictive power. Supervised machine learning provides a systematic way of selecting which factors matter and in what way, which is useful for predictions. This predictive power could greatly improve policy design and evaluation.8

Currently, the use of machine learning for prediction is more prevalent in the commercial world. Software for a video streaming service can predict what people might enjoy, based on the past choices of similar user profiles. But such software cannot yet determine which children are most at risk of dropping out of school. However, as Sendhil Mullainathan of Harvard University points out, these types of problems are in fact similar.9 They require predictions based on, implicitly or explicitly, lots of data.

Many areas of policy could benefit from machine learning, especially where prediction is important. For example, hospital doctors try to anticipate heart attacks so they can intervene before it is too late. Manual systems currently correctly predict this with about 30% accuracy. Sriram Somanchi and colleagues from Carnegie Mellon University, however, have created a machine learning algorithm that predicts heart attacks four hours in advance of the event, with 80% accuracy (as tested on historical data).10

In Singapore, SingHealth together with GovTech also used machine learning to identify potential frequent admitters based on data such as medical history and demographics. The algorithm predicted with 80% accuracy, the probability of each patient’s likelihood of returning to the hospital. This information could aid hospital staff to focus on patients with high predicted risk of returning, in order to reduce the number of readmission.11

Limitations of Machine Learning

While the thoughtful application of machine learning to policy has many advantages, it cannot be applied to every policy problem. There are a number of caveats that policymakers need to be aware of when applying machine learning:

- Prediction, not evaluation

Where a policy decision depends on a prediction of risk, machine learning can help inform this decision with more accurate predictions. For example, it can help social workers determine the quantum and duration of financial assistance that recipients should receive based on their profile, or help hospitals identify which patient may be at higher risk of becoming a frequent admitter. However, predictions cannot unveil the cause-and-effect relationship between policy interventions and outcomes. To uncover causation, policymakers need to use other evaluation tools such as randomised controlled trials. In addition, just because something is predictable does not mean that decisions should be made solely on predictions. For example, even if an algorithm predicts that an applicant seeking financial assistance has a greater likelihood to fall short of the programme’s requirements, this does not mean that the application should be rejected outright without reviewing other aspects of the case.12 - Define the outcome in a clear and measurable way

Being able to measure the outcome concretely is a necessary prerequisite to predicting.13Machine algorithms are most helpful when applied to a problem where there is not only a large history of past cases to learn from, but also a clear outcome that can be measured. On its own, a prediction algorithm will focus on predicting its specified outcome as accurately as possible, at the expense of everything else.14Any other outcomes, no matter how significant, will be ignored. In a ground-breaking project by Kleinberg et al,15machine learning is used to predict which suspect should be detained in jail pending trial and which can be released on bail.16The estimates show that if the release decisions were made using this low-cost algorithm instead of relying on judges’ judgment, the crimes committed by suspects on bail could reduce by 25%. In this example, the algorithm treats every crime (past and present) as equal, whereas judges may, quite reasonably, place disproportionate weight on whether a suspect had previously committed a very serious violent crime. In such cases, an algorithm may not always predict the desirable outcomes. When using machine learning, it is important for policymakers to clarify what they care about most, and what they might be leaving out. If the outcome is hard to measure, or involves a hard-to-define combination of outcomes, then the problem is probably not a good fit for machine learning. - Quality of training dataset

The success of any algorithm depends entirely on the quality of the training dataset it has to learn from. If the training data does not capture all the factors that affected previous outcomes, it can mislead the algorithm. For example, if judges previously based their decisions on whether family members showed up at court to support the accused (thereby displaying strong family support), this aspect needs to be captured in the dataset. Otherwise, the algorithm would not be able to factor this into its analysis, and it may recommend the release of more suspects without family support than desirable.17For machine learning to be useful for policy, it must accurately predict “out-of-sample”. That means it should be trained on one set of data, then tested on a data set it has not seen before. When training an algorithm, policymakers should withhold a subset of the original dataset, then test the finished algorithm on that subset to verify its accuracy.18 - Retaining human judgement

Ultimately, an algorithm cannot capture all the factors that impact the outcome of a policy intervention. Other than leveraging on trials and experiments to verify the actual impact on the ground, the element of human judgement remains important. Machine learning can look at millions of cases in the past and extract what happened on average. But it is only the human who can see the extenuating circumstances in any given case, which might have not been captured in the training dataset. The human-machine team can be more effective than either one alone, using the strengths of one to compensate for the weaknesses of the other.19

Conclusion

To reap the full benefits of data science, governments need to systematically collect, share, as well as manage the sensitivities of using data. Beyond new approaches to collecting, analysing and presenting data, developments in data science have immense potential to work with other policy tools, such as behavioural insights, to bring about changes that benefit individuals and society.

By helping people to visualise the effects of their immediate actions, governments can address biases such as hyperbolic discounting20 and “not in my backyard syndrome”, by making the future costs of their actions more salient and more personalised. This presents many opportunities to nudge people to “do the right thing” in areas such as public health, public transport, and the environment. At the same time, policymakers need to be aware of potential issues arising from the use of data, such as privacy protection and the risk of data-based discrimination.21

It is important to recognise that human intervention is key to the success of using data. Data science is excellent at identifying patterns and making predictions, but it does not tell policymakers what to do with the patterns and the predictions, nor does it offer solutions. To solve real-world problems, human judgement in designing and evaluating possible solutions remains irreplaceable.

NOTES

- Daniel Diermeier, “Data science meets public policy,” The University of Chicago Magazine, Jan-Feb 2015, accessed 6 December 2016, http://mag.uchicago.edu/university-news/data-science-meets-public-policy.

- James Guszcza, “The Last-Mile Problem,” Deloitte Review, Issue 16, accessed 6 December 2016, https://dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/deloitte-review/issue-16/behavioral-economics-predictive-analytics.html.

- Government Technology Agency of Singapore.

- Artificial intelligence is a broad term that refers to applying to any technique that enables computers to mimic human intelligence, using logic, if-then rules, decision trees, and machine learning.

- Executive Office of the President National Science and Technology Council Committee on Technology, “Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence,” October 2016, accessed 7 January 2017, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/whitehouse_files/microsites/ostp/NSTC/preparing_for_the_future_of_ai.pdf (PDF, 1.2MB).

- Ibid.

- The text analytics platform <www.govtext.com> is available to all public officers with a .gov.sg email.

- On how economists can use machine learning to improve policy, see: Susan Athey, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, accessed 6 December 2016, https://siepr.stanford.edu/.

- “Of prediction and policy,” The Economist, 20 August 2016, accessed 6 December 2016, http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21705329-governments-have-much-gain-applying-algorithms-public-policy.

- Ibid.

- Data Science Division, Government Technology Agency of Singapore.

- Jon Kleinberg, Jens Ludwig and Sendhil Mullainathan, “A Guide to Solving Social Problems with Machine Learning,” 8 December 2016, accessed 3 January 2017, https://hbr.org/2016/12/a-guide-to-solving-social-problems-with-machine-learning.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Bail is a temporary release of an accused person waiting trial, sometimes on the condition that a sum of money is lodged to guarantee their appearance in court.

- Refer to Note 12.

- Refer to Note 12.

- Refer to Note 1.

- Hyperbolic discounting is a bias that places more emphasis on current gains versus future costs, which are of equal value.

- Derrick Harris, “Why big data has some big problems when it comes to public policy,” Gigaom, 27 August 2014, accessed 16 December 2016, https://gigaom.com/2014/08/27/why-big-data-has-some-big-problems-when-it-comes-to-public-policy/.