Embracing Complexity in Healthcare

ETHOS Issue 14, Feb 2016

Regarding Complexity

Complexity derives from the Latin plexus, meaning “interwoven”. Most phenomena can be classified into multiple levels of complexity. Simple phenomena are usually straightforward, with predictable linear cause-and-effect relations, for example, the collisions of billiard balls on a pool table. Complicated phenomena involve numerous components and steps; much like a recipe for baking a cake, if all the ingredients are available and the given steps followed correctly in a controlled environment, the outcome is predictable and replicable.

Complex phenomena, however, consist of elements that are not entirely knowable ex ante, predictable or within our control — as such, there can be no ‘cookbook’ for managing them; they may be modelled or simulated, but they cannot be fully controlled. Complex tasks (such as parenting, where what works for one child may not be applicable to another) can only be approached through guiding principles and ongoing improvisation until they are complete.

Governments, economies, and even families are some human systems we know intuitively as complex: they involve multiple entities with different roles, functions, agendas and decision-making processes, a diverse network of interactions, an evolving environment, and multiple concurrent activities. These characteristics lead to a common property of complex systems: unpredictability in the interactions and outcomes of the entities and the system as a whole. This is a case of the whole system being greater than the sum of its parts.

”Health care is the most difficult, chaotic and complex industry to manage today.”

— Peter Drucker, on hospital management, Managing in the Next Society (2002)

Complexity in Healthcare

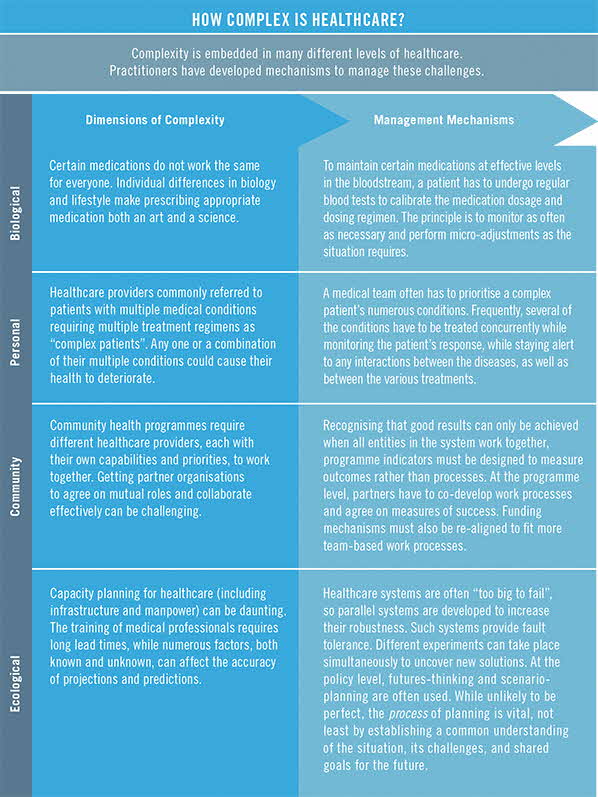

To state that healthcare is complex is ironically to oversimplify the issue. Healthcare is a spectrum, encompassing issues that range from the simple to the complex. A blocked artery in the heart can cause a heart attack — that is a straightforward cause-effect relationship, classifiable as simple. The procedure employed to unblock the blocked artery) is complicated, and should only be attempted by a trained specialist. The subsequent treatment of the patient through medication and lifestyle changes at the very least borders on being complex (i.e., patients react and behave differently, and have differing attitudes towards health). At a systems-level, trying to plan and prepare for ageing-related health issues against a backdrop of a greying population is several orders of magnitude more complex than managing an individual patient. Across the entire system, there are simply too many factors that may influence the future (for example, new treatment modalities, shifting attitudes towards health and ageing, uptake and efficiency of preventive health services, emerging diseases, changing healthcare financing models, etc.), operating at multiple levels, for any mid- to long-term prediction and planning to hold perfectly true.

Such categorisations only take into account the service delivery aspects of healthcare. The level of complexity increases even further when we consider other aspects, such as the following:

- Healthcare financing. Economists have highlighted healthcare as a sector in which the free market approach does not work well, due to information asymmetry, adverse selection, entry barriers, monopolies, oligopolies and other market failures. In some cases, actions to correct for market imperfections may generate unforeseen effects from various agents in the system which could even end up working against the original intent of the intervention.

- Behavioural dynamics in healthcare. Poorly designed healthcare systems can generate perverse incentives for providers and lead to over-servicing of patients. Medical insurance can also lead to moral hazard and a tendency for patients to over-consume healthcare. “Affect heuristics” mean that patients may make less rational and highly unpredictable healthcare decisions (e.g. when receiving bad medical news).

- Healthcare as a nested system. Healthcare systems are interlinked with other equally complex systems in society. Personal values and culture, political rivalries and agendas, scientific developments, academic competition are often taken as orthogonal to each other, but in fact often contribute ripples and knock-on effects throughout society and its nested systems.

Why View Healthcare Through a Complexity Lens?

Planners have typically used a reductionist1 approach to solve difficult problems. Such an approach is a useful way to deconstruct problems into smaller, more manageable components, but it has known limitations. It may provide the answer for certain problems, but will not explain why a solution works in one situation but not in another. The use of such an approach to explain and simplify the current challenges facing healthcare is tempting but it is easy to forget that the manner in which entities work more often than not depends on the environment in which they operate. For instance, it is not enough to have the correct people come together to work on a planned solution — success calls for an understanding of how these people work together to find the correct solution. The quality of relations between entities in a system matters.

Acknowledging that healthcare is complex, along different dimensions, presents planners with new perspectives and opportunities. Healthcare practitioners, planners and leaders should understand that beyond technical skills and book knowledge, their competence in a complex world is a function of culture, which is in turn a function of relationships. This may be counter-intuitive for many institutions and policymakers accustomed to clear answers and concise bullet points. Humility is required to recognise that the success of an initiative is dependent not just on having the right solution, but also the right selection and mix of individuals in the programme. Creating the right entities and the right environment, rather than centrally planning solutions, is the more successful and liberating approach in the long term.

Healthcare as an industry has a substantial service component; the people providing the service are sometimes as important as the products themselves. The customer experience is heavily dependent on the interactions between consumers and service providers. A conventional linear solution to a hospital bed shortage might be to build more facilities and train more staff, but such an approach would be inadequate if it fails to take into account the relevant human interactions and relationships: it would solve a quantitative problem, but create a qualitative one.

Any shift to a complexity-based approach should be gradual; the capability and capacity for perceiving, understanding and addressing complex problems must be built up over time — for both the individual and the system. This will take time and effort, but is a necessary investment to cope with an increasingly complex healthcare landscape.

The Need for Change

On the other hand, planners who recognise that they are dealing with problems of a complex nature may find that this new approach frees them to be more open to experimentation and innovation. Old models may need to be dismantled before new systems can take their place. Governments that have traditionally taken on a strong centralised approach to healthcare planning may have to acknowledge the limitations of this approach and re-examine their roles in a more complex operating environment. This does not mean discarding all strategic planning processes. Instead, it means retaining and strengthening certain key functions (the broad parameters of planning, for instance), while spinning off or even creating new entities catering to the more localised planning that complex systems often require.

In the new era, the public will become increasingly responsible for co-creating the healthcare landscape they want or believe in. This also means that citizens will have to rethink their own roles in healthcare consumption, advocacy, philanthropy and sector development.

Such a fundamental shift will generate systemic tensions, which can be mitigated and managed if the necessary changes in both government and citizenry take place at a similar pace.

Approaching complexity in healthcare at different scales

Many complex healthcare issues have no obvious solutions or clear-cut right or wrong answers. The choice to be made is often between two imperfect sets of solutions, each with its own strengths and limitations. How might we approach them?

Organisational scale: A hospital newly tasked with caring for its surrounding community may initiate open dialogue with community partners to seek new ideas or new models of care. In such a context, the soft systems methodology — where stakeholders are asked to put aside their organisational personae, and think about action in an idealised realm — may help. It allows the individuals a safe zone where they can step away from the messiness of immediate issues, and look at the whole system from fresh perspectives. This can also help all stakeholders to generate idealised models towards a shared vision, and illustrate the tensions between ideal and reality. While different stakeholder perspectives and priorities will not have gone away, there is now greater collective awareness of legitimate differences, and the process of seeking accommodation (distinct from consensus) can take place. If done well, the process can help to build trust within the group, and bolster its ability to deal with challenges in the future.

Governmental scale: To understand end-of-life issues and design a comprehensive strategy to manage them, a government must first accept that science is poorly equipped to tackle certain social challenges. In a pluralistic society, any answer that attempts to shoehorn end-of-life issues into a single neat package is bound to fail. Instead, appreciative inquiry can be useful, particularly in seeking to build understanding instead of trying to find solutions. The focus of the inquiry is not on the problem, but on the possibilities, opportunities and strengths of current stakeholders. If done well, this approach creates a context for deep dialogue and reflection that can expand the boundaries of our knowledge and imagination. Perhaps the hardest part of this transformative approach is letting go of the habit of seeking exclusively to solve problems.

National scale: Falling birth rates is a multi-faceted and highly complex issue. Nations dealing with this problem may decide to reframe the narrative of family and child-rearing. Transition management offers a framework for managing these large-scale ecological changes, by allowing the vision to take shape on a blank canvas, in an arena with multiple stakeholders. Often, the vision is not fixed in details, but encompasses a broad view of possible futures, and the final outcome is left to broader stakeholder engagement and co-creation processes. The process of transition management has been likened to being more akin to “midwifery” than “engineering”.

Source: Philippe Vandenbroeck, Working with Wicked Problems (Brussels, Belgium: King Baudouin Foundation, 2012)

Policy Planning: A New Approach

The policy planning role needs to shift from prediction and control to fostering relations and creating enabling conditions for teamwork and success. When planners have successfully incorporated a complexity-based approach to their work, the next skill they will have to learn is to govern through a few simple “rules of the game”.2

If planners get caught up trying to manage complex systems with increasingly complicated policy structures, they will lose the agility and light-touch that is inherently necessary to shape such systems. Instead, planners should aim to lead by setting “rules of the game” and then monitoring (instead of micromanaging), while different agents co-develop the landscape and co-evolve with time: an indicator of maturity and resilience in the ecosystem.3

This complexity-based approach also reframes policy planning and managerial activities to emphasise sense-making, learning and improvisation, while letting healthcare providers take on decisions about care — decisions that should be undertaken by people who understand the need for care. Governments and planners can wield substantial influence through their policy interventions, but they should also encourage people to voluntarily coordinate their actions for a common good.

When governments with a strong tradition of central planning adopt a complexity-based approach for healthcare sector planning, the experience can be both liberating and nerve-wracking for the planners and the system as a whole — as it is with any voluntary surrender of control.

Obliging planners to assume responsibility for the health of the entire system can crowd out important stakeholders and may marginalise partner organisations vital to the healthy functioning of the system. But where planners relinquish a certain level of control, new voices may speak up more comfortably, allowing partners and stakeholders to develop new capabilities and emergent solutions to take shape.

Planners can then take on new roles as enablers, gradually transferring more granular planning, operations and control to partner organisations. Such a transition will not be simple or quick; it may also be fraught with issues of trust and bouts of disappointment. Learning, growth and development, both at the personal and organisational level, often starts in such a place of discomfort — where evolution begins and energy is created. The worse alternative is not to evolve at all.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following persons for their inputs towards this article: A/Prof John Abisheganaden, Mr Peter Ho, Dr Benjamin Koh, A/Prof Kenneth Mak, MG (NS) Ng Chee Khern, Dr Ng Yeuk Fan and Mrs Tan Ching Yee.

NOTES

- Reductionism is the idea that a system can be understood by examining its individual parts.

- Complexity science tells us that simple rules can lead to intricate, unpredictable yet effective patterns of collective behaviour. Examples in nature abound: the mass migration of locust swarms, the evasive manoeuvres of a school of fish when attacked, and how a colony of ants functions as a super-organism. Scientists have commented that nature is frugal: of the possible rules that could be used to govern interactions among agents, often only the simplest are in effect, e.g. (1) move in the same direction as your neighbour, (2) remain close to your neighbours, and (3) avoid collisions with your neighbours.

- One example is the way in which the Institute of Medicine exercised its influence over the complex US healthcare landscape. Informed by complexity science, it was able in 2001 to focus the entire healthcare sector on “Six Aims for Improvement”: to be Safe, Effective, Patient-centred, Timely, Efficient and Equitable. This approach was much more effective compared to if the Institute had micromanaged improvements for each individual entity in the system. See: Institute of Medicine, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century” (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2001).

FURTHER READING

- Alberts, David S. and Richard E. Hayes. Planning: Complex Endeavors. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense Command and Control Research Programme, 2007.

- Bar-Yam, Y., S. Bar-Yam, K.Z. Bertrand, N. Cohen, A.S. Gard-Murray, H.P. Harte, and L. Leykum. “A Complex Systems Science Approach to Healthcare Costs and Quality.” In Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health, 855–877. Springer, 2013.

- Colander, David and Roland Kupers. Complexity and the Art of Public Policy: Solving Society’s Problems from the Bottom Up. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Drucker, Peter. Managing in the Next Society. New York, N.Y.: Truman Talley Books, 2002.

- Evidence Scan: Complex adaptive systems. The Health Foundation, August 2010. http://www.health.org.uk/publication/complex-adaptive-systems

- Flake, Gary William. The Computational Beauty of Nature: Computational Explorations of Fractals, Chaos, Complex Systems, and Adaptation. Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books, 2000.

- Institute of Medicine, 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.

- Lim, Jeremy. Myth of Magic: The Singapore Healthcare System. Singapore: Select Publishing, 2013.

- O’Hara, Maureen and Graham Leicester. Dancing at the Edge: Competence, Culture and Organization in the 21st Century. Axminster, Devon: Triarchy Press, 2012.

- Vandenbroeck, Philippe. Working with Wicked Problems. Brussels, Belgium: King Baudouin Foundation, 2012. www.kbs-fre.be