Economic Development and Social Integration: Singapore’s Evolving Social Compact

ETHOS Issue 14, Feb 2016

The Singapore Story: Social Mobility and Opportunities for All

In a 2014 interview with the Gail Foster group, Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam pointed out that while many think of Singapore as an economic success, it is the “social integration of our citizens and our institutions that has fostered an unusual degree of social mobility in our first four decades and that defines Singapore’s development story”.1 This compact between economic and social strategies2 has been a remarkably consistent theme in the development of Singapore. In the first few decades after Independence, socially oriented policies — including the provision of public housing, education and healthcare — promoted social stability and built up a capable, productive workforce attractive to foreign investment. Early successes in fulfilling these public needs gave the Singapore Government a longer runway to develop long-term, rational economic strategies for growth. This association of economic development with social wellbeing would come to underlie the relationship and social contract between Singaporeans and their Government in the years to come. As the late Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee put it: “It is dangerous to execute an economic development plan which has reference only to economic variables, important though these are… The creation of wealth, which is what economic development is about, is basically a simple process. All it requires is the application of modern science and technology to production, whether in agriculture, mining or industry… What is more difficult to achieve is a social and political order that enables development to take place. Where a stable political system is achieved, progress can be spectacular…”3

Those who have done well on merit through the Singapore system have an obligation to give back to the society that enabled them to succeed.

Consistent with this social contract, public assistance was kept low to encourage self-reliance and effort; individuals would work hard to support themselves and their families to the best of their own efforts and abilities, while the Government would “provide all its citizens with the same opportunities to make the best that they can of their available talents, … skills and abilities to rise to the position for which they are best fitted”.4 Economic growth and the steady rise in affluence soon buoyed up Singaporeans, who enjoyed intergenerational mobility in incomes and educational attainment across the social spectrum.5

New Economic Strategy and A New Social Compact

In the 1990s and early 2000s, however, the Singapore Story began to take a turn, as the economy shifted to more knowledge-based activities, moving up the value-chain in response to the challenges of globalisation, technological change and other pressures. Since workers in a less developed economy tend to start from a lower base, the returns from education and skills develop are easier to reap, as was the case in Singapore’s early years. A more advanced, knowledge-based economy generates more value, but calls for higher order skills which yield greater productivity but are more difficult to acquire. Workers with these advanced skills, or who can call upon networks, abilities and resources that are not easily substitutable, are in great demand and can command much higher wages. Conversely, low-skilled workers in an open economy, whose efforts can be replaced by automation or cheaper labour, will see their wages depressed and may require more support beyond what they can readily achieve through their own efforts alone.

Policies continued “to ensure that every Singaporean has equal and maximum opportunity to advance himself, while providing a social safety net to prevent the minority who cannot cope, from falling through”.6 Measures were introduced to redistribute Singapore’s budget surpluses back to Singaporeans to enhance their assets and to defray essential expenses7 such as services and conservancy, and utility charges. Explaining new measures to support the needs of lower-income households in 2001, then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong argued that “… higher-income Singaporeans owe their success in part to the others who support our social compact. They must, therefore, be prepared to lend a helping hand to those among us who are not so well off. Only then can we remain a cohesive and stable society. It cannot be every man for himself. For a person to succeed, he needs a launch-pad from society. … In turn, lower-income Singaporeans must support the enterprise and efforts of those who have the ability. We must not resent those who create wealth, for themselves and for Singapore.”8

This “paradox of active government support for self-reliance” requires Singaporeans to retain their personal drive and dignity as part of this compact.

Mr Goh’s statements outlined a new dimension in Singapore’s social compact, expanding its scope beyond the creation of fair opportunities for all Singaporeans to highlight a greater sense of collective responsibility. Those who have done well on merit through the Singapore system have an obligation to give back to the society that enabled them to succeed. This entails mitigating social inequality and helping those who are less able to progress.9 In an iteration of the social compact of collective responsibility, and mutual support, successful individuals would also be expected to contribute to society by helping their less fortunate counterparts through philanthropy, volunteerism and community service.

Active Government Support for Personal and Community Responsibility

While government efforts to temper inequality and sustain social mobility gained momentum in the mid-2000s, they continued to be premised on healthy economic growth, seen as the best way to create jobs, raise incomes and provide more resources with which to provide social support. As Deputy Prime Minister and then-Finance Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam put it: “To be able to help the poor, we must first create wealth, grow our GDP and provide every incentive for Singaporeans to strive and work to improve their lives and that of their families.”10

Mr Tharman also added that “The solution for Singapore cannot be to grow slowly in order to reduce inequality. If we do that, it will only hurt the people we are trying to help. Slow growth will make everybody worse off, but it will have the harshest impact on those at the bottom. Jobs will be lost and incomes will fall for those at the lower end of the workforce, while at the top end, those with the talent or entrepreneurial ability to seize opportunities elsewhere will up and go. Slow growth will not assure us of a more equal society, as long as we live in a globalised world.”11

Financial assistance for low-wage workers and vulnerable households was institutionalised with the introduction of ComCare in 2005, and Workfare in 2007. These programmes, along with the Silver Support Scheme to be implemented in 2016, present a significant shift from Singapore’s traditional policy stance, in which financial assistance is positioned as short-term and temporary to avoid eroding personal drive and responsibility.

Efforts to redistribute wealth has also increased in recent years with adjustments to the tax rates of top income earners and the employers’ contribution rates to the Central Provident Fund — Singapore’s national retirement savings programme.

Even though the Government has expanded its responsibilities in social support and redistribution, the social compact between the Government and Singaporeans has in essence, remained unchanged where “there is active government support for personal responsibility, rather than active government support to take over personal responsibility or community responsibility”.12 This “paradox of active government support for self-reliance”13 requires Singaporeans to retain their personal drive and dignity as part of this compact.

Moving Toward A More Progressive Tax Regime

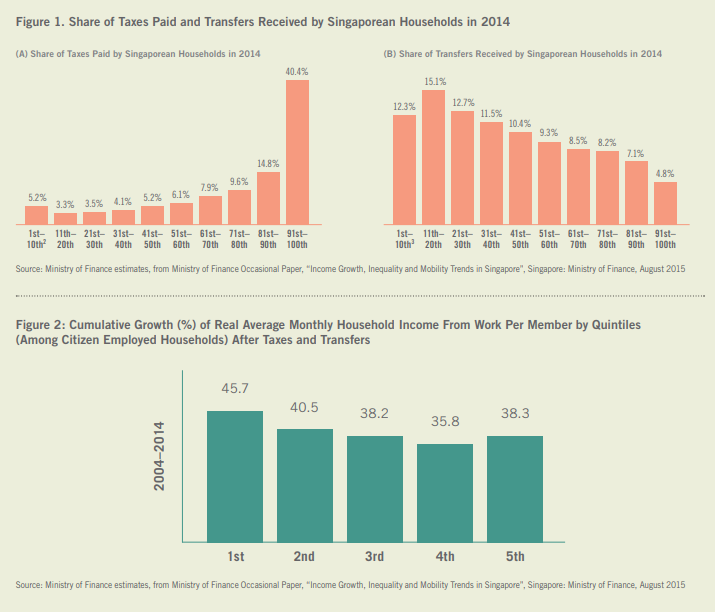

In Singapore, higher income households contribute to “the bulk of taxes” and lower-income households receive the “bulk of benefits”1 (Figure 1). This approach has positive downstream effects on income growth and particularly benefits households in the bottom 20% by income. In the last decade, the real incomes of this bottom segment have grown faster than households in the top 20% (Figure 2).

To ensure that the tax system remains progressive and fair, the Singapore Government will increase the marginal tax for the top 5% of income earners in 2017.

Notes

- 2015 Budget Debate Roundup Speech by Deputy Prime Minister and then-Finance Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam.

- The first decile of households (by incomes per member) paid a higher proportion of taxes than the second decile. This arises because not all the households in the 1st decile are poor. This can be seen from the profile of the first decile households: 16% of them live in private properties, 13% in HDB 5-room and Executive flats, 14% own cars, and 10% employ a maid.

- The first decile of households (by incomes per member) received a lower proportion of benefits than the second decile.This arises because not all the households in the 1st decile are poor. This can be seen from the profile of the first decile households: 16% of them live in private properties, 13% in HDB 5-room and Executive flats, 14% own cars, and 10% employ a maid.

Maximising Individuals’ Opportunities Throughout Their Lives

While Singapore’s meritocratic system rewards individuals fairly for their efforts, “it will not on its own sustain social mobility”.14 There are signs that social mobility for lower-income households is declining, and that there is an increased correlation between the education attainment15 of parents and their children. This has raised concerns that the starting conditions could become a significant determinant of social mobility, that initial endowments of wealth, class, social networks and parental investment could override individual effort, drive or ability.

These concerns are not unfounded. A recent UK study on social mobility revealed that 35% of children born to parents of higher social class with higher educational attainment tend to obtain higher earning jobs, even though they might have lower academic ability compared to their counterparts from lesser advantaged backgrounds.16 This is because wealthier parents can draw on their resources and networks to maximise skills and outcomes for their children.17 Furthermore, studies have shown that the increase in social mobility and the returns to investment in skills tend to diminish over the long term.18 Ironically, countries that are more meritocratic and mobile can be expected to experience a greater decline in mobility down the line. 19

While notions of merit and how to determine the ‘best person for the job’ continue to evolve, there has also been a shift in policy emphasis towards a continuous meritocracy that evaluates people throughout their lives, not one where things are set based on academic performance at a young age.20 Efforts to raise the overall quality of pre-school education learning support for vulnerable children, along with policies to ameliorate the impact of entrance criteria21,22 and key examinations have developed in tandem with initiatives (most notably SkillsFuture, announced in 2014) to build a stronger and broader foundation for life-long learning opportunities so that all Singaporeans can better themselves throughout their lives. 23 These and other new approaches should help to shift public cultural perceptions of ability and value that have a profound influence on how inclusive our economy and society is prepared to be, which in turn will impact social mobility.

Augmenting Retirement Savings for Older Workers

The Central Provident Fund (CPF) – Singapore’s national retirement savings programme – has also seen policy changes towards more progressivity in the past decade.

Between 2003 and 2006, the Government lowered the CPF contribution rates of older workers aged 50 to 55 (who tend to receive higher seniority-based salaries) to ensure that they remain more employable, particular during economic downturn or restructuring. From 2012 however, the emphasis on job protection was shifted to give older workers nearing retirement greater assurance that their CPF savings would be adequate. Their CPF savings were augmented through transfers as well as enhanced interest rates,1 and their CPF contribution rates are to be restored to similar levels as their younger counterparts from 2016.

Notes

- To enhance retirement savings, the Government will implement a 1%-increase in interest rates on the first $60,000 of CPF balances for all CPF members; older members aged 55 and above will receive an additional Extra Interest of 1% on the first S$30,000 of their CPF balances from 1 January 2016.

The Future of Inclusive Growth and Social Mobility

In a column for the New York Times, Noble Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz commended Singapore for “having prioritised social and economic equity while achieving very high rates of growth over the past 30 years”.24 Stiglitz argues that rent-seeking by the wealthy25 has prevented wealth distribution and poverty alleviation from taking place in the US, resulting in inequality becoming entrenched. By contrast, he lauds Singapore for avoiding such pitfalls by actively pursuing a balance between social and economic integration, and through its commitment to preserving social mobility without compromising incentives to excel. This balance, as reiterated by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam,26 remains a key priority in Singapore’s development:

It’s impossible for our economy to have succeeded without effective social strategies — most importantly, enabling people to develop their potential through education, and housing policies that provided a sense of equity… But it’s also impossible for us to have experienced the substantial and broad-based improvement in social well-being and life satisfaction without a vibrant economy — and the large increase in real incomes, across the whole span of the workforce…

Nevertheless, this balance will become increasingly more challenging to sustain, particularly in a small, open and maturing economy. Growth is expected to slow down even as social needs continue to expand, while tax burdens have to be kept low enough to keep Singapore globally competitive in order to continue to create jobs, lift incomes, and accrue the resources we will need.

It is fitting that, in this context, collective responsibility and mutual support have taken on a greater significance in Singapore’s economic and social stance, but the success of this new dimension of Singapore’s social compact will depend on cultural rather than technical factors. As social values change,27 qualitative judgements of fairness and equality will become just as important as quantitative indicators of policy effectiveness in influencing the public’s acceptance of public policies.28

Normative discourse on what Singapore defines as success, merit and fair reward will determine what trade-offs and policy options will be most effective in equalising opportunities and sustaining social mobility. In the long term, Singapore will need to embark on an iterative process of engagement and negotiation of these rapidly evolving markers and issues. There will not be any easy answers.

NOTES

- “Singapore’s Lessons: An Interview with Tharman Shanmugaratnam,” interview by Gail Fosler, October 9, 2013, accessed January 12, 2014, http://www.gailfosler.com/singapores-lessons-an-interview-with-tharman-shanmugaratnam.

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, “Economic Society of Singapore SG50 Distinguished Lecture”, August 14, 2015.

- Goh Keng Swee, then Minister of Defence, speech at the Opening of the Seminar on Modernisation in Southeast Asia at the University of Singapore, January 17, 1971.

- Goh Keng Swee, “Man and Economic Development,” in The Essays and Speeches of Goh Keng Swee: The Economics of Modernization, Singapore: 2013, Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited, pages 45-50.

- Yip Chun Sing, “Intergenerational Income Mobility in Singapore,” Singapore: Ministry of Finance, January 13, 2012 and Ministry of Finance Occasional Paper, “Income Growth, Inequality and Mobility Trends in Singapore,” Singapore: Ministry of Finance, August 2015: 16–17.

- Goh Chok Tong, National Day Rally 2001, speech at the University Cultural Centre, National University of Singapore, August 19, 2001.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Elaborating on this theme in 2013, Goh Chok Tong highlighted a more compassionate meritocracy where opportunities are accessible to “the whole of society and not just the brightest and most able” nor “those who are lucky in their backgrounds and genetic endowments”. See: Goh Chok Tong, speech at the Raffles Homecoming 2013 Gryphon Award Dinner, July 27, 2013.

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, 2008 Budget Debate Round-Up Speech, February 27, 2008.

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, 2010 Budget Debate Round-Up Speech, March 4, 2010.

- The Economic Society of Singapore SG50 Distinguished Lecture by Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, August 14, 2015.

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, The 6th S Rajaratnam Lecture (Fairmont Ballroom, Raffles City Convention Centre, Singapore, December 2, 2013).

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, “Economic Society of Singapore SG50 Distinguished Lecture”, August 14, 2015.

- These trends are revealed in Yip Chun Sing, Intergenerational Income Mobility in Singapore, Singapore: Ministry of Finance, January 13, 2012; Irene Y. H. Ng, “Intergenerational Income Mobility of Young Singaporeans,” YouthSCOPE, 1, 40-57, Singapore: National Youth Council, 2006; Irene Y. H. Ng, “The Political Economy of Intergenerational Mobility: Implications for Singapore’s Skills Strategy” in Skills Strategies for an Inclusive Society: The Role of the State, the Enterprise and the Worker, eds Johnny Sung and Catherine Ramos (Singapore: Institute of Adult Learning, 2014): 142-171.

- “Well-off Families Create ‘glass floor’ to ensure children’s success, says study”, The Guardian, July 26, 2015.

- Abigail McKnight, “Downward Mobility, Opportunity Hoarding And The ‘Glass Floor’,” UK Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission Research Report, London: June 2015.

- M. Nybom and Jan Stuhler, “Interpreting Trends in Intergenerational Income Mobility,” Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (Institute for the Study of Labor), Discussion Paper No. 7514, July 2013, 31.

- Ibid.

- Rachel Chang, “Meritocracy here should be continuous: Tharman,” The Straits Times, September 6, 2012.

- Vincent Chua, “The Network Imperative,” in Skills Strategies for an Inclusive Society: The Role of the State, the Enterprise and the Worker, eds Johnny Sung and Catherine Ramos (Singapore: Institute of Adult Learning, 2014).

- Forty places are reserved for students with no familial or alumni connections in each primary school. Children who gain priority admission into primary schools through the proximity criteria have to be residing at the residential address for at least 30 months before registration.

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, 2015 Budget Debate Roundup Speech, March 5, 2015.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Singapore’s Lessons for an Unequal America,” The New York Times, March 18, 2013.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd, 2013).

- Tharman Shanmugaratnam, The Economic Society of Singapore SG50 Distinguished Lecture, August 14, 2015.

- Ronald Inglehart and Paul R. Abramson, “Economic Security and Value Change,” American Political Science Review 88(1994): 336-54.

- Hoang Van Khanh Do and Sharon Tham, Survey Of “Fairness Perceptions In Singapore, Public Policy”, Singapore: Civil Service College, 2014.