Wage Inequality, Intergenerational Mobility and Education in Singapore

ETHOS Issue 03, Oct 2007

Accompanying Singapore’s phenomenal economic growth over the past four decades has been a rapid increase in educational attainment over the years:1 in 1960, the mean years of schooling for residents aged 25 and over was 3.14 years; in 2006, it was 9.3 years. This dramatic increase in the supply of skilled labour in all sectors of the economy helped to power Singapore’s high growth rates over the past few decades of economic development, which also saw declining wage inequality and high upward intergenerational mobility in education.

However, we need to ask if these trends will continue in the future and whether underlying socioeconomic and demographic changes may challenge or reverse the macroeconomic dynamics underlying Singapore’s past decades of growth.

DIMINISHING UPWARD MOBILITY?

Singaporeans born in the first 10 years of independence were likely to have enjoyed high upward mobility for two reasons. First, they could easily overtake their parents in terms of educational attainment as the preceding generations tended to be more lowly educated on average. Second, there were tremendous investments and innovations in public education in the early years of nation building.

However, as the Singapore economy has matured to a lower steady-state growth rate, with average years of schooling reaching that of advanced countries, upward mobility in education is likely to be diminishing. In terms of wage inequality, the trend has been a downward path till the late 1990s, as observed by Ho and Hoon.2 However, recent structural changes in the world economy have increased wage inequality in the small open economy of Singapore. These and other underlying trends may affect upward mobility in Singapore and determine areas of interest for future policies.

A SKILL BIAS IN PARENTAL INFLUENCE

Recent studies on advanced economies have shown that skill-biased technological progress has pushed up wage inequality. In the case of Singapore, as studied in Ho and Hoon,2 international outsourcing has the same effect as skill-biased technological progress, and hence it opposes the impact of higher educational levels in reducing wage inequality.

There is another skill-biased process in educational transmission from parents to children. Skilled parents are usually more educated, earn a higher income, are more able to invest in the education of their children privately, and more capable of coaching their children in their studies. Educated women are more likely to marry educated men and have fewer children. All these behaviours of skilled parents combine to result in a skill-biased parental influence on the educational attainment of their children, resulting in a tendency towards lower mobility and lower wage equality. Empirically, Ng and Ho3 found that the father’s education has a statistical significant influence on the educational attainment of the youth: about 16.3% to 16.8% of this economic status is transmitted.

BROKEN FAMILIES REDUCE EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

In 1980, Singapore’s general divorce rate per thousand married resident females in 1980 was 3.4 but by 2006, it had escalated to 8.0 per thousand. More alarmingly, the general divorce rate for married resident males aged 20 to 24 in 2006 was 52.0 per thousand!

A divorced mother needs to devote more time in market activities to make a living. As a consequence, less time is given to the child in educational supervision. The child may also incur some psychological cost as a result of the marital breakup. The Emotional Quotient and Social Quotient of a child from a broken family could be lower than that of children from intact families enjoying love and care from both parents.

Our study in Ng and Ho3 has shown that youths whose parents are divorced will see a statistically significant reduction of their educational attainment by 1.8 to 1.9 years worth of schooling. A Swedish study has also demonstrated that children who have experienced family dissolution or reconstitution show lower educational attainment at age 16.4

Policies aiming to enhance upward mobility should therefore take into consideration changing trends in the structure of families in Singapore, particularly so in different ethnic and social groups. Consider the statistics in 2005: the general divorce rate for Malays was 15.5 per 1,000 married resident females, compared to that of the Chinese at 6.6 per 1,000; single parent-registered births per 10,000 female residents for Malays were also higher than the Chinese at 10.6 and 1.5, respectively; 5.4% of Malays in the primary one cohort were admitted to local publicly funded universities as compared to 30% for the Chinese community.

EXPANSION OF TERTIARY EDUCATION

High upward educational mobility in the past was mainly a result of the expansion of public education. The educational link to employability is important as a higher return to education via public subsidy will lead to higher mobility and higher wage equality.

The educational link to employability is important as a higher return to education via public subsidy will lead to higher mobility and higher wage equality.

As Singapore climbs up the educational ladder, there seems to be a call for diversity in educational products and providers apart from the Government, as well as an expansion of tertiary education. Diversity is good, but attention should be given to the marketability of human capital accumulated, that is, the market return on education. Economic models and empirical studies have shown that private schools could have a negative impact on educational mobility as they rely more on the contribution from parents both in terms of time and money. Skill-biased parental influence is more prominent in private schools. As Singapore moves to become the educational hub of the region and beyond, we will see more private and international schools and universities entering the education industry. We have to be aware of the potential impact on educational mobility and wage equality, given a larger share of private schools in the economy.

POPULATION EXPANSION AND SKILL-BIASED IMMIGRATION

Singapore is targeting to achieve a larger population of 6.5 million, from the current level of 4.5 million, despite a low total fertility rate (1.26 per resident female in 2006). If the expansion of population is to be facilitated primarily by immigration, particularly skill-biased immigration, then skilled immigrant parents will have an advantage over less skilled residents in terms of educational investment in their children. As a result, skill-biased parental influence may be strengthened and upward mobility reduced because skilled parents will invest more in their children’s education than unskilled parents. However, skill-biased immigration will also increase the number of skilled workers relative to unskilled workers, resulting in an increase in upward mobility. The net effect on upward mobility is therefore ambiguous. It is, however, unambiguous that wage equality will be reduced by both effects. With population expansion, increased investment in public education, especially tertiary education, is necessary; otherwise, competition for limited places in university will lead to higher wage inequality and lower upward mobility.

CONCLUSION

Skill-biased parental influence and the damage of dysfunctional families must be considered in any policy designed to deal with upward mobility and wage inequality. The targeted enlarged population may also bring about higher wage inequality if it is facilitated mainly via skilled immigration. While the net impact of an enlarged immigrant population on educational mobility is uncertain, increased public spending on education, especially tertiary education, may become necessary to prevent any possible decline in mobility.

Wage inequality and intergenerational mobility in education are jointly influenced by variables such as structural changes in technology, demography, and government policies in education and the labour market.

UPWARD EDUCATIONAL MOBILITY: A DEMAND AND SUPPLY PERSPECTIVE

Wage inequality and intergenerational mobility in education are jointly influenced by variables such as structural changes in technology, demography, and government policies in education and the labour market.

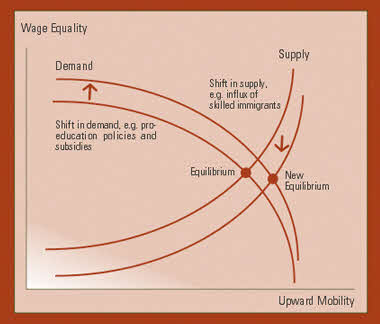

A demand-supply framework of upward mobility allows us to analyse the impact of trends on wage inequality and intergenerational mobility simultaneously. Wage equality, defined as the ratio of unskilled wage to skilled wage, can be considered the price of upward mobility and influences how parents decide on educational investment in their children. When wage equality is low (unskilled wage is low relative to skilled wage), parents have a greater incentive to invest in their children’s education because of the low opportunity cost and high return of educating an unskilled child into a skilled adult. The increased demand for education when wage equality is low will lead to high upward mobility. Socioeconomic, demographic, and policy shocks (for example, a change in government subsidy to public education) which influence returns and parental decisions on education, will shift the demand curve of upward educational mobility.

A high upward mobility will also imply a larger pool of skilled workers relative to unskilled workers. All else being equal, the level of skilled wages relative to unskilled wages will decrease, resulting in greater wage equality. This positive relationship between upward mobility and wage equality may be interpreted as a supply curve for upward mobility. Structural changes in technology or conditions in the labour market will shift the supply curve of upward mobility.

FIGURE 1.THE BALANCE BETWEEN WAGE EQUALITY AND UPWARD EDUCATIONAL MOBILITY

The intersection of the demand and supply curves will give the equilibrium level of upward mobility and wage equality in society. – Ho Kong Weng

NOTES

- Singapore’s real GDP (in 2000 market price terms) grew an average of 5.53% per capita per year from 1961 to 2006.

- Ho, Kong Weng and Hoon, Hian Teck, “Service Links and Wage Inequality.” (Working Paper 0301, Department of Economics, National University of Singapore, 2003).

- Ng, Regina and Ho, Kong Weng, “Intergeneration Educational Mobility in Singapore: An Empirical Study”, YouthSCOPE (2006): 58–73.

- Jonsson, Jan O. and Gahler, Michael, “Family Dissolution, Family Reconstitution, and Children’s Educational Careers: Recent Evidence of Sweden,” Demography 34 (1997): 277-93.