Workfare: The Fourth Pillar of Social Security in Singapore

ETHOS Issue 03, Oct 2007

What is Workfare? Workfare is often thought to refer to the income supplement that will be given to low-income workers from January 2008.

It is more than that. Workfare in Singapore refers to the philosophy that work is the best form of social assistance. Anyone who is able to work should be helped to find a job and earn a salary that is enough to support himself and his family. Manifested in concrete policies, Workfare reinforces the work ethic of Singaporeans and makes it worthwhile for anyone at the margin to offer up his labour to the economy.

The development of Workfare marks a milestone in the history of social assistance to low-income Singaporeans. When it was announced, it came as a surprise to some Singaporeans weaned on a diet of strict anti-entitlement and anti-dependency rhetoric. As late as 2005, the nation’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew was reiterating the reasons why after a short-lived Fabian phase in the 1950s, the Government departed from the idea of creating a welfare state: “I soon realised that before distributing the pie I had first to bake it. So I departed from welfarism because it sapped a people’s self-reliance and their desire to excel and succeed.”

However, in spite of its generous trappings, Workfare is not a radical departure from the nation’s fundamental values. It reinforces the values of hard work and self-reliance that had long existed in Singapore society. Workfare is firstly a pragmatic response to the effect of globalisation and technology on wage dispersion. Second, it is a creative way of boosting what you get for doing something.

HOLISTIC FRAMEWORK

Although Workfare is often associated with its income supplementation component, it is actually a framework around which six major initiatives work in concert to ensure the well-being of low-wage and vulnerable but work-capable Singaporeans (Figure 1).

Workfare has to address not only the needs of the low-wage worker, but also those of his family; not only his ability to earn a living wage but his incentive to upgrade as well. If families suffer extended periods of unemployment, uncertainty and low wages, there is a danger that the negative attitudes and mindsets of discouraged workers could be transmitted to their children, doing irreparable harm to the work ethic and attitude of the next generation. Short-term assistance can easily drift into long-term dependency. By discouraging families from asking for help until they are at a crisis point, we are not solving problems that might benefit from early intervention.

Workfare aims to incentivise work and increase opportunities for low-wage workers to support themselves, build assets and facilitate social mobility.

FIGURE 1. SUPPORTING THE LOW-WAGE WORKER

The first thrust, “Rewarding Work”, is targeted at encouraging inactive low-skilled Singaporeans to enter and stay in the workforce by making work financially worthwhile through the Workfare Bonus and later the Workfare Income Supplement (see box story). It is also focused on helping low-wage workers to build up assets for the future, with additional housing subsidies for first-time buyers of Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats. The grant was recently expanded in August 2007 to an eligibility ceiling of S$4,000 and a maximum quantum of S$30,000.

The second and complementary move provides “Social Support to Enable Work” through the Self-Reliance Programme and the Work Assistance Programme. Assistance includes measures such as intensive case management to help low-income households with financial planning, and employment facilitation for the unemployed. Child care and student care subsidies were raised to reduce impediments to work. In line with the experience of Wisconsin, USA, sanctions such as blackout periods or disqualification are imposed on households who fail to cooperate in carrying out their employability plans, or reject jobs on offer.

The third key element ensures that Workfare recipients develop higher skills for better jobs. Many Workfare regimes elsewhere had emphasised inducements to work at the expense of training and upgrading programmes. Criticisms were rife that Workfare was pushing people to ‘get a job, any job’, condemning them to a life of drudgery in various low-paying McJobs; Singapore, on the other hand, had the opposite bias, one towards the primacy of training over monetary benefits. Although the proportion of students progressing to post-secondary education has been rising with each cohort, a significant number still leave the system without post-secondary qualifications. Efforts have been made to ensure that children who are less academically inclined are still work-ready and equipped with employable skills, especially in the service sectors.

Since Workfare can only be effective if job seekers can find work, the fourth prong involves “job re-creation” efforts to redesign and scale up existing low-paying jobs such as cleaning and healthcare into higher-paying, higher productivity jobs for Singaporeans.

The last permanent initiative is to create “Hope for the Future”. Most low-income households regard their children as a ticket to greater social mobility. It is critical for the nation’s future to allow these children to progress educationally so that they would not be locked in a permanent underclass. It is important also to make quality preschool education available to all, to re-enthuse those in danger of dropping out of school, and to support the development of children from vulnerable households that face multiple challenges such as job loss, divorce and abuse.

The integrated case management approach that has been adopted departs from the looser many-helping-hands approach of conventional community support. While more intensive and more expensive, it should be capable of delivering more lasting outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Workfare is a multifaceted approach to a global problem, customised to Singapore’s unique social conditions and institutions. It is also a creative attempt to combine elements of wage supplementation and subsidy models. Nevertheless, these are early days yet for the scheme and the jury is still out on its success in raising take-home pay, increasing labour supply and providing some income mobility. These trends will be monitored carefully over the next three years.

Over the years, the primacy of economic growth has been coupled with a strong focus on almost free high-quality education and asset accumulation via the provision of subsidised housing for over 80% of Singaporeans. The former investment gave Singaporeans the wings to elevate their lot, and the latter gave them the roots to stay.

WHY WORKFARE?

Over the years, the primacy of economic growth has been coupled with a strong focus on almost free high-quality education and asset accumulation via the provision of subsidised housing for over 80% of Singaporeans. The former investment gave Singaporeans the wings to elevate their lot, and the latter gave them the roots to stay.

Social assistance was dispersed throughout the community and the family was regarded as the first avenue for support. There was no unemployment insurance or benefits, healthcare was subsidised but not free; food or transport vouchers were deemed unnecessary. Monthly Public Assistance payouts averaging S$309 were only given to about 3,000 Singaporeans incapable of work and bereft of family support. The philosophy was to give little and demand little.

As long as wages and the ranks of the middle class grew continuously, any poverty could be dismissed as a marginal or a cyclical issue best addressed with temporary measures. This was the approach during the recession in 1985–86, the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, and the SARS downturn in 2003. The Government instituted programmes to help those who were temporarily unemployed such as the Interim Financial Assistance Scheme and the Work Assistance Programme.

BEYOND THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

In May 2000, the media reported a Department of Statistics disclosure that the lowest 10% of society had an average monthly income of only S$75.81. The Government swiftly refuted this by pointing to their possession of hand phones and television sets, as well as home equity in HDB flats due to an aggressive home ownership policy. By 2003, the majority of the lowest 20% of Singaporean households owned HDB 3-room or 4-room flats with average home equity of at least S$100,000.

It only became obvious that the problem of the working poor was a structural and not a cyclical problem when the economy started to recover in late 2004. While the media focused on a Gini coefficient that had risen from 0.442 in 2000 to 0.468 in 2005,1 growing income inequality was not in itself to be feared. Indeed, some degree of income inequality was to be expected as a result of good growth.

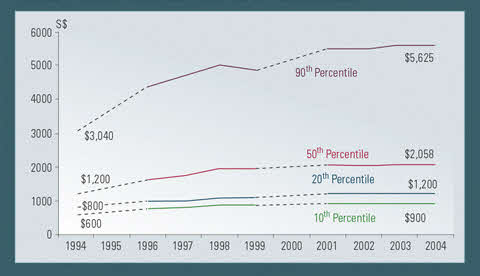

The worrying phenomenon was real wage stagnation and structural unemployment. Wages at the low-end failed to keep pace for the first time since 1965. Despite a buoyant job market from 2004 to 2006, real wages of the lowest 30% of workers (i.e. those earning wages up to S$1,500) in Singapore fell by 0.5% per annum. Between 2000 and 2005, the average monthly household income from work among employed households in the first two deciles fell in real terms. By contrast, the real wages of the 9th decile worker rose by 2.9% p.a. in the same period.

FIGURE 2. GROSS MONTHLY INCOME BY PERCENTILES

The profile of the low-income group gave policymakers little to be optimistic about. Nearly two-thirds of the bottom quintile had below secondary education and another 24% had only secondary schooling. Of these, about 10% were drop-outs. Those with less education were empirically more likely to have greater employment insecurity and lower income potential in an increasingly skills-biased labour market.

Thirty per cent of low-income households earned less than S$1,625 or half the median resident gross monthly household income—a larger proportion of the resident workforce than a decade earlier. The majority were primary breadwinners. One startling fact was how vulnerable they and their families were to any kind of shock—sudden illness, injury, unemployment.

There were two obvious responses. The first was to introduce protectionist measures, including the reservation of jobs for Singaporeans or the imposition of a minimum wage. However, in a small open economy, this would only serve to lower competitiveness, retard economic growth and depress living standards across the board. The only other option was to specifically address the downsides of globalisation: to provide some kind of cushion for the worst affected, and hope for their children.

MAKING WORK PAY

The conundrum the Government faced was how to increase support for vulnerable workers without increasing dependency. This was a different question from countries with higher welfare and social transfers, who aimed to crimp benefits and reduce welfare rolls.

The first answer was to make work a condition of aid, but to expand the range and depth of assistance. The ‘work-based’ welfare reform enacted in places like Wisconsin, USA impressed Singapore policymakers because of the emphasis placed on a strong work ethic and personal responsibility. Most welfare systems (including Singapore’s) fundamentally disbursed aid on the basis of need, even if some work and training requirements were loosely tied. In Wisconsin, the principle of reciprocal responsibility was brought to its logical conclusion—by making aid conditional on work. Flat grants were given regardless of the number of children that depended on the workfare recipient, just as workers get a flat salary independent of the number of children they have.

The second insight was that the Government should focus its aid not only on the unemployed or those on welfare assistance, but on the majority of low-wage workers. When work is not an obviously superior option, the rational decision for welfare recipients would be to remain on welfare. In Hong Kong, for example, it was not uncommon for an unemployed person in Hong Kong to get a better deal on welfare than in a low-paying job. Any expansion of our safety nets should therefore increase the incentives for people in work to work, as well as to entice those not working to participate. - Jacqueline Poh

Negative income taxes and a wide range of other programmes have existed for some time in which governments provide income support to workers based on their wages. Economic theory suggests that as long as the demand for labour is not inelastic, wage supplementation will help increase the incomes of workers as well as encourage more people to enter or remain in the workforce.

WAGE SUPPLEMENTATION

Negative income taxes and a wide range of other programmes have existed for some time in which governments provide income support to workers based on their wages. Economic theory suggests that as long as the demand for labour is not inelastic, wage supplementation will help increase the incomes of workers as well as encourage more people to enter or remain in the workforce.

Despite criticisms that wage supplementation would reduce the intensity of effort, well-designed programmes appear to have been effective in moving people to work, without disincentivising them from working harder. In the US, labour force participation increased due to the Earned Income Tax Credit, without a corresponding decrease in hours worked.2 This could be because the key decision faced by workers is whether to work, rather than how many hours to work.

While employers could theoretically game the system and negotiate away any increase in take-home pay, the higher the elasticity of labour demand, the less likely employers will reduce wages in response. In view of the buoyant economic growth and the large number of jobs created in Singapore in the last two years, it was felt that labour demand was likely to be elastic, making it an ideal time to commence the supplementation scheme.

The Workfare Income Supplement (WIS) is unique among “negative income tax” schemes. Instead of being linked to the taxation system, it is tied to the Central Provident Fund (CPF) since it is the only scheme in Singapore where workers make universal contributions.

The Government would:

- Give cash supplements to workers whose incomes are below a certain threshold but who can prove that they have worked for a minimum time over a specified period.

- Adjust downwards the amount of contributions that employers make to the CPF of older low-wage workers, making it more attractive for them to hire this group and give them a chance to prove themselves.

- Supplement the CPF savings of the low-income individual. As a result, the worker would enjoy both a higher take-home pay and greater employability. The employer enjoys a reduced payroll and an incentive to hire vulnerable older workers. The payouts more than offset the reduction in the employers’ contributions to their workers’ CPF.

In the 2007 Budget, the WIS was finally made a long-term scheme, cementing Workfare as the fourth pillar of Singapore’s social security system, along with the CPF for retirement, the 3Ms (Medisave, Medishield and Medifund) for healthcare and HDB subsidised housing. The WIS scheme is expected to benefit 438,000 Singaporeans up to $2,400 a year. – Jacqueline Poh

NOTES

- The Gini coefficient of Employed Households, based on ranking of resident households with income earners by per capita monthly household income from work. From: Department of Statistics, General Household Survey 2005 (Singapore: Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2006).

- Eissa, Nada and Liebman, Jeffrey, “Labor Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (1996): 605-37.