A New Consensus for Growth in the 21st Century

Digital Special Edition (Dec 2020)

The Need for a New Development Model

Promoting economic growth has been a top priority of policymakers in most countries, not only because it is a crucial measure of prosperity creation but also because it contributes to the political legitimacy of governments. The pursuit of economic growth is shaped not only by a country’s factor endowments and comparative advantage but also by the soundness of its economic model.

Since the late 20th century, several well-known development models have emerged to stimulate growth through economic and institutional reforms, particularly in developing countries. Of these, the Washington Consensus (WAC) and Beijing Consensus (BEC) have captured notable attention and generated considerable debate.

The WAC originated from a discussion paper by J. Williamson outlining a set of policy reforms by which developing countries could promote economic development (see Figure 1).1

Figure 1. Ten Reform Prescriptions Recommended by the “Washington Consensus”

Source: J. Williamson (1990)2

The BEC model, on the other hand, is focused on strategic approaches instead of operational prescriptions. Examining China’s historic level of success with economic reforms, J. Ramos proposed three guiding principles (or “theorems”) essential for economic development in developing countries: innovation, quality of life, and self-determination (see Figure 2).3

Figure 2. Three Theorems Defining the “Beijing Consensus”

Source: J. Ramos (2004)4

While the WAC and BEC models both offer valuable insights for policy reforms to promote economic development, they are not robust enough to be effective development models for the 21st century, due to three limitations.

1. The models are viewed by many policy experts as representing competing ideologies, which hinders efforts to better understanding their complementarities.

2. Applications of these models have, in many cases, lacked sound strategic mechanisms. Instead, their effects have been distorted by immediate operational urgency or political and emotional reasoning. For example, under WAC guidance, Latin America’s economic growth was “half of what it had been from the 1950s through the 1970s when the region followed other economic policies”, according to noted economists Narcís Serra and Joseph Stiglitz.5 Embracing the BEC model plausibly contributed to the severity of Venezuela’s economic crisis, in which the economy contracted by nearly 50% over a decade.6

3. The global development environment is constantly shifting, often in profound ways. In particular, the digital revolution and globalisation have generated unprecedented opportunities and challenges for economic development. These new dynamics, however, are not well captured in the WAC and BEC models, which were conceived at a time of much steadier innovation and lower levels of international integration.

The digital revolution and globalisation have generated unprecedented opportunities and challenges for economic development.

Features of the New Developmental Model

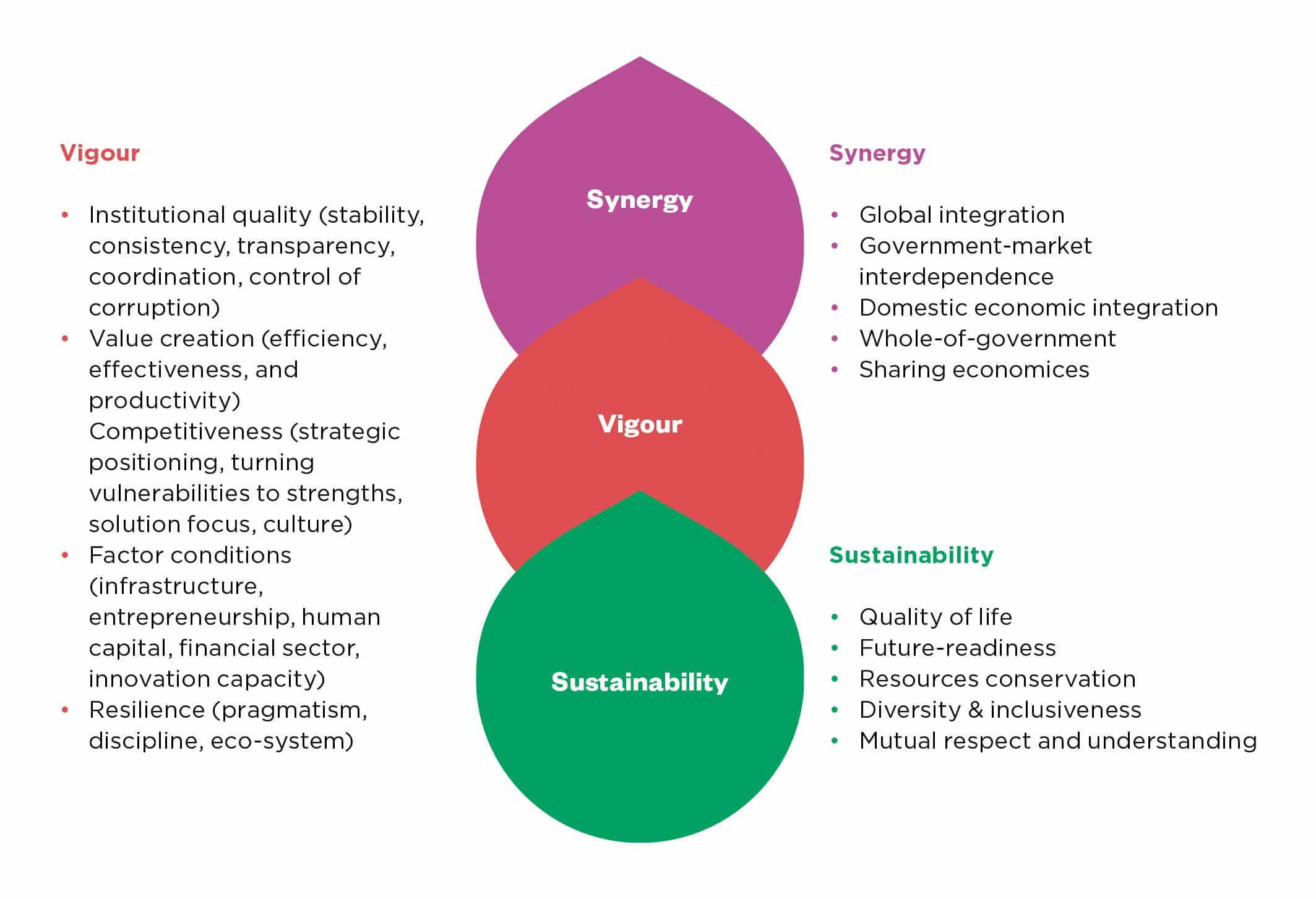

A new development model for the 21st century should meet at least two criteria. First, it should overcome the limitations of existing models. Second, it should go beyond questions about “what” and “how”—which respectively characterise the WAC and BEC models—to focus on “why.” In this spirit, we propose a new model based on three core components: synergy, vigour, and sustainability (see Figure 3).7

Figure 3. Proposed Development Model

Source: M. K. Vu (2020)8

Synergy emphasises the strategic importance of creating value through synergistic development efforts. It centres on five essential approaches:

I. Deepening global integration to precipitate synergies between domestic factor endowments and global market forces, especially by promoting exports and attracting foreign direct investment.

II. Strengthening government-market interdependence. An effective government enables markets to function more efficiently; in return, a healthy market enhances government efficiency and effectiveness. Singapore’s exemplary development history has shown how government can leverage markets to address development challenges more effectively.

III. Fostering domestic economic integration and cross-sector collaboration.

IV. Embracing a whole-of-government approach to building institutions, with an aim to facilitating coordination and coherence in policy initiatives.

V. Enabling innovative market platforms such as the sharing economy (e.g., Grab, Gojek, and Airbnb).

Vigour concerns efforts to boost economic robustness. It involves five principal approaches:

I. Enhancing institutional quality, for which top priorities are macroeconomic stability, policy consistency, transparency, coordination capabilities, and control of corruption. In promoting business investment and economic growth, improving predictability can be even more urgent and effective than reducing transaction costs.

II. Emphasising value creation throughout reform and investment initiatives, as facilitated by improved governance efficiency and effectiveness to boost productivity. While efficiency focuses primarily on operational measures, effectiveness focuses on establishing a solid foundation for sustained growth. This ranges from increased transparency and trust-building to promoting structural transformation in view of future-readiness.

III. Strengthening competitiveness to maximise economic potential at any given level and type of factor endowment. This approach requires a government to adopt a smart strategic position for leveraging factor endowments and participating in global economic integration. It also requires a government to turn vulnerabilities into sustained and unique advantages through targeted policy and resource appropriation, creative thinking, and structural flexibility for adapting to a constantly evolving global economic landscape.

IV. Promoting investments and strategic efforts to upgrade production factors and boost productivity, including infrastructure, human capital, entrepreneurship, innovation capacity, and financial systems.

V. Enhancing economic resilience by embracing pragmatism, discipline, thoughtful reflections, and continuous reforms to strengthen the economic ecosystem.

Sustainability represents efforts essential for maintaining growth and development in ways that do not compromise future capabilities to do the same. This also involves five basic approaches:

I. Declaring quality of life as the primary goal of development efforts. A guiding principle is whether an initiative improves the lives of citizens. Related urban policy issues include air quality, crime, green space, and public transport, while social policy issues include education, health care, cost of living, and access to welfare services.

II. Enhancing future-readiness across all segments of society. This requires governments to embrace global mega-trends and foster transformation that prepares the economy and stakeholders eventualities—both anticipated and otherwise. Efforts should address three areas: digital transformation in infrastructure, services, skills, and other capabilities; global integration through international standards in education and workforce development, trade liberalisation, and multi-lingualism—particularly English fluency, which facilitates communication with global partners and access to global knowledge networks (e.g., through the Internet); and prudent and forward-looking urbanisation (e.g., smart cities, management of service delivery, and liveable city initiatives).

III. Fostering resource conservation (especially in water, land, and energy) and proactively addressing climate change. This necessitates not only foresight in planning and resource appropriation but also transitions in energy production, delivery, and usage. Investments in renewable energy must be seen as an urgent strategic priority.

IV. Promoting human diversity and inclusiveness regarding ethnicity, religion, gender, and all other dimensions. Such efforts ensure that all members of society have a stake in development and can realise their fair share of the gains.

V. Promoting conduits of sharing, understanding, and mutual respect among all members of society. While institutional and policy measures regarding inclusiveness are crucial, interpersonal interactions are where the experience of inclusiveness is lived first-hand. Fostering such an environment of social cohesion and “heartware” calls for narrative building around the appreciation of diversity, the importance of listening to others, and the value of empathy and generosity. The outcomes of such efforts not only improve the lives of everyone but also make progress towards the building and maintenance of trust in society and its institutions. This principle calls for the efforts to build harmony not only within the country but also between the country and its neighbours and partners.

Synergy is relevant to all three strategic approaches, both explicitly and implicitly. In preparing for the complex and interconnected challenges of the 21st century, the concept of synergy is an indispensable guiding principle in the design of systems, institutions, and policies. Synergy can be defined as the process of identifying, establishing, and nurturing an ecosystem such that the complementary function of its subsystems produces impacts greater than the sum of its parts. Embracing the principle of synergy in both the short- and long-term makes the task of building vigour and sustainability more efficient and strategic.

In addition to the three components, the proposed model emphasises the strategic importance of embracing Industry 4.0. Digital technology can strengthen development efforts in two ways. First, it augments each component. For example, digital connectivity and platforms lower the costs and barriers for interorganisational “synergies”, robotics, automation, and other smart technologies foster industrial “vigour”, and sensor networks for monitoring environmental quality enhance “sustainability”. Embracing digital technology also benefits development efforts across three components by improving the quality of decision making, promoting the formation of virtual ecosystems of innovation and production, and generating data—one of the most valuable resources in the 21st century.

The Case for Singapore and Implications for ASEAN

The proposed development model reflects many features observable in the Singapore development experience. For example, regarding synergy, Singapore is a world leader in reaping benefits from global integration, embracing government market interdependence, and embracing a “whole-of-government” approach to institutional development. These characteristics have made Singapore a popular global partner in commercial endeavours and a popular model for designing initiatives to reform government, enhance productivity, and improve strategic visioning. Many multinationals have rooted their presence in Singapore because this partnership not only enhances their productivity but also strengthens their strategic capabilities to reap greater gains from the rise of Asia.

In terms of vigour, Singapore has become known globally for emphasising elements of good governance, establishing targeted economic positioning and national branding, leveraging strengths such as location, and turning vulnerabilities into strategic advantages. For example, the country has embraced the “City in a Garden” concept, leveraging tropical greenery to overcome the environmental disadvantages of hot weather and high humidity. Land scarcity has inspired the city-state to become a world leader in innovative urban management solutions, from the integration of land use and transportation planning to public housing and environmental infrastructure. Furthermore, Singapore’s shortage of natural resources has made the country highly committed and strategic in investing in their people and boosting their productivity, which have enabled Singapore to boast a world-class education system and a top-notch start-up ecosystem.

Singapore's shortage of natural resources has made the country highly committed and strategic in investing in their people.

Regarding sustainability, Singapore has committed considerable levels of resources, research, and policy efforts to improve liveability, fortify key urban assets against the impacts of climate change, and promote diversity and social inclusiveness. Singapore demonstrates how public policies can help cultivate a national narrative towards ethnic and religious harmony.

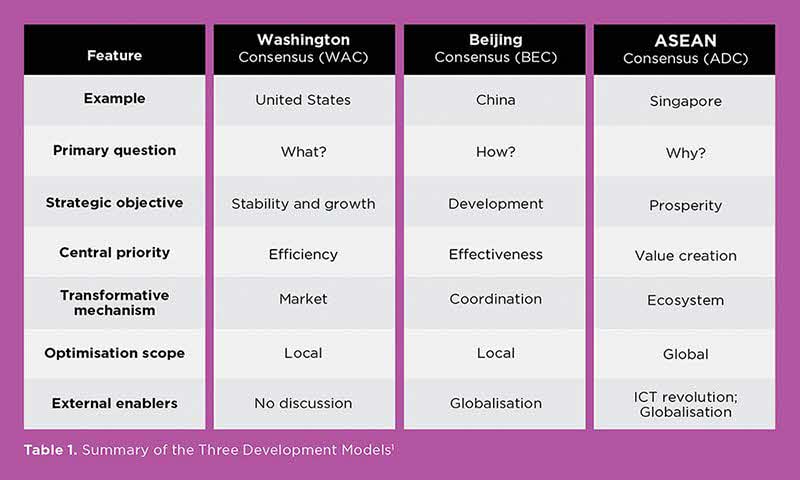

While the United States and China are respectively examples of the WAC and BEC models, Singapore is an example for the ADC model.

WAC, BEC and ADC Compared

While the United States and China are respectively examples of the WAC and BEC models, Singapore is an example for the ADC model. Although clearly evolved from WAC and BEC, the ADC places its primary focus on the “why” question and thus goes further than both models (which concern the “what” and “how” questions, respectively).

Furthermore, ADC focuses on value creation as articulated by a comprehensive framework that includes synergy, vigour, and sustainability; by contrast, WAC is preoccupied with efficiency and BEC on coordination effectiveness. Additionally, ADC emphasises ecosystem-building as the primary mechanism to create value, while WAC relies on the market and BEC on government interventions.

Like Singapore, the other ASEAN countries are characterised by strategic location, diversity, and strong development aspirations. Given these circumstances, the region is well positioned to embrace a new development model that we might term the “ASEAN Development Consensus” (ADC). Adopting such a model would make the region’s development efforts more purposeful, coherent, and mutually reinforcing. It would also provide a signal to the world that the rise of ASEAN is fuelled not only by the rapid growth of individual countries but also, more crucially, by the robust synergy, vigour, and sustainability of its ecosystem, grounded in a sense of shared vision and commitment to the region’s common prosperity. This should bolster ASEAN’s global economic and political position in the decades to come.

It should be noted that the strength of a country or region comes not only from soft power or hard power but also from its navigating capability. As the world is becoming increasingly volatile, uncertain, and complex while Asia is rapidly rising, an inspiring vision and a clear joint development strategy will avail ASEAN of further global economic strength and political influence in the decades to come.

Note

- M. K. Vu, “Economic Catch-up Strategy in the 21st Century: From Concept to Action”, book project, 2020, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

A Policy Framework for Action

Although the ADC model provides a robust strategic framework for promoting economic development, the pace and extent of its implementation will vary widely by country, depending on a number of factors in concert. These include:

• the respective country’s level of readiness;

• the pressures (internal and external) that compel the country to improve economic performance;

• leadership vision;

• government coordination capability;

• enabling conditions, including the external environment and technological progress; intangible impediments to progress, including legacy systems, outdated regulations, and old-fashioned mindsets; and

• obstacles caused by selfish motives and corruption.

This suggests that a country’s low level of readiness can be due to direct factors such as poor leadership vision and weak coordination capabilities, as well as indirect factors such as widespread corruption and outdated mindsets and legal systems.

Enhancing readiness to embrace a new development model is a substantial step for any country, including Singapore.

Southeast Asia, along with the rest of the world, continues to experience profound changes in economy, society, and the environment. The first step in embracing a new growth model is to establish a vision that clearly captures aspirations for the future with a broader and more visionary prospect. For Singapore, the vision of being an “outstanding” country or “best” place in various aspects is no longer effective: a new era calls for updated thinking and goals. To embrace the ADC, a more appropriate vision might be “an inspiring example of development and a meaningful contributor to building prosperity and peace in ASEAN and Asia”. Singapore should envision the ASEAN community in the same way as Switzerland might view Europe: an economically dynamic region in which it can make key contributions through political influence and leadership in finance, innovation, and knowledge industries.

To pursue initiatives supported by the ADC model, the government and other stakeholders could adopt our SMART framework, which we developed in 2017:9

• Strategic choice-making, concerning national positioning, global integration, and the embrace of the digital revolution;

• Monitoring a set of key performance indicators (KPIs);

• Accountability assigned to government agencies for each subset of KPIs;

• Rethinking fundamental development concepts; and

• Trust building among society, the government, and the private sector.

These elements could serve as a diagnostic tool for policymakers to determine their country’s performance, indicating areas on which to focus reform and development efforts.

Enhancing readiness to embrace a new development model is a substantial step for any country.

Conclusion

The 20th century saw transformative progress in economic development, global integration and cooperation, and social mobility. Post-war reconstruction efforts and the international development initiatives of wealthy countries and multilateral institutions like the United Nations and World Bank produced considerable reflection about which models of development are most effective. The WAC and BEC are two paradigms that emerged, based on the successful experiences of some large global powers. They provided useful explanations and some degree of productive guidance for countries seeking to escape the cycle of low development.

However, the 21st century brings unprecedented challenges and opportunities for development, opening a new era for economic development and prosperity creation. It is fair to consider whether the old development models of the 20th century are still appropriate as policy guidance. We have proposed the ADC as an alternative model based on the nature of urgent circumstances facing most of the world today.

To build a robust ecosystem for the future, countries will need to identify, understand, and mainstream examples of achievement, competence, and incorruptibility in the public sector, while also building a social environment characterised by passion, compassion, and integrity. By assuming the role of pioneers in adopting the ADC, the ASEAN countries could harness a type of “navigation power”—or, first-mover advantage in shaping the concept and narrative of 21st century development—that has the potential to be more valuable and appreciated than the typical forms of soft power and hard power to which most nations have long aspired. One can anticipate that the strength of a nation or a region in the 21st century would come more from how much the world wants to come to it to learn than from how much resources it has.

In embracing ADC, ASEAN and similarly situated countries can empower themselves to transform their economies, societies, and environments, not merely “catching up” to highly developed countries but charting a new course beyond—one defined by unique perspectives and strengths that have often been overlooked by legacy development models. Singapore has an opportunity, and indeed even a calling, to be a leader in this new thinking for 21st century development.

NOTES

- J. Williamson, “What Washington Means by Policy Reform”, in Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has Happened (Institute for International Economics, 1990), chap. 1, 90–120.

- See Note 1.

- J. Ramos, The Beijing Consensus, Notes on the New Physics of Chinese Power (London: Foreign Affairs Policy Centre, 2004), 2011.

- See Note 3.

- N. Serra and J. E. Stiglitz, eds, The Washington Consensus Reconsidered: Towards a New Global Governance (Oxford University Press, 2008), 4.

- Venezuela’s GDP grew at an average annual rate of -5.8% over the period 2008 to 2018.

- M. K. Vu, “Economic Catch-up Strategy in the 21st Century: From Concept to Action”, book project, 2020, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

- See Note 7.

- M. K. Vu, and K. Hartley, “Promoting Smart Cities in Developing Countries: Policy Insights from Vietnam”, Telecommunications Policy, 42, no. 10 (2017): 845–859, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. telpol.2017.10.005