Nurturing the Continuing Education and Training Ecosystem

ETHOS Issue 29, Nov 2025

The Continuing Education and Training (CET) Ecosystem

Commemorating ten years of the SkillsFuture movement in May 2025, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong highlighted that Singapore is at the global forefront of attempting to nurture and embed a national culture of lifelong learning and continuous growth. The engine of this effort is described as a "complex ecosystem" of "institutions, partners and stakeholders", with PM Wong emphasising that this drive is not the purview of any one ministry, but is instead a whole-of-society, national movement.1

In business and innovation studies, an ecosystem refers to a set of interdependent actors (firms, users, institutions, intermediaries) whose interactions and resource flows co-create value beyond what any single actor could produce alone.2 The mesh of players in an ecosystem benefits from sharing capabilities and complementarities, from innovation through collaboration, and from a greater range and depth of learning and policy influences.3

Singapore's CET ecosystem comprises the government agencies (especially its sibling lead agencies SkillsFuture Singapore and Workforce Singapore), the Institutes of Higher Learning (IHLs), training providers in the private sector, adult educators and trainers, employers, trade associations, and the labour movement as represented by the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC). The learners themselves, synonymous with the workforce, are both players and beneficiaries within the ecosystem.

While the vision of a national skills ecosystem forging ahead as one is persuasive, it is less clear whether all the key players today recognise and embrace the roles they need to play for this approach to yield meaningful outcomes for all. We might ask: Are win-win arrangements open to the entire CET ecosystem? Does each player group view other players, including market competitors, not as antagonists but as possible partners with which to combine strengths for even greater impact?

We may have room to do better at harnessing and deepening our ecosystem advantages. Conversely, if uneven development in an ecosystem were allowed to persist, it could be detrimental to the whole, with the weakest link holding back the pace at which a sector develops.

The Adult Learning Collaboratory

The Adult Learning Collaboratory (ALC) was launched by SUSS-IAL in August 2024. Supported by SkillsFuture Singapore (SSG), the ALC aims to foster collective innovation to tackle wicked problems in and associated with adult learning, drawing on insights from IAL's research. The ALC takes an ecosystem approach: stakeholders comprising enterprises, researchers, training providers, learners, adult education professionals and more come together to undertake use-driven co-creation, with every partner jointly invested and working collaboratively to reap benefits for all.

Through innovations based on research insights, the ALC anchors the co-creation process with experimentation and testing to ensure real-world and use-driven relevance, as reflected in the merging of the terms 'collaboration' and 'laboratory'.

The ALC is currently focused on three projects:

AI Capabilities for a Multi-Generational Workforce

- As AI tools become ever more sophisticated, it is not enough to equip the workforce with basic AI literacy and fluency. Employers are indicating that AI skills need to be accompanied by the ability to contextualise its use for each particular job, and to go beyond standard AI-generated solutions for work tasks. The ALC is thus putting forward pedagogies in AI capability development initiatives and programmes which look to build creator abilities with AI for the non-technical community. An ecosystem approach ensures that workforce capabilities with technology are developed with each stakeholder group's needs in mind.

New-Age Business Transformation

- Our research shows that a people-first business transformation approach would benefit small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in particular. An easy-to-administer diagnostic tool offering incisive, actionable recommendations for SMEs seeking stronger performance is showing promise in tests, giving business owners a new lens to undertake business transformation. The ecosystem co-change methodology in testing now has potential to bring together SMEs, consultants and researchers on this journey.

Future-Oriented Pedagogies

- Current modes of teaching and learning are not particularly well suited to nurturing learners comfortable with dealing with the complex and the emergent at work. The ALC's experimentation methodologies are testing ALC-created techniques across a range of organisation, enterprise and institution types to engender this future orientation, and these efforts are starting to show signs of changing pedagogical practices in the learning space. Many are starting to shift from the mindset of learning as acquisition to that of learning as a means of knowledge-building. This will need more time to be embedded as a key habit at work.

With continued experimentation and resulting data analysis, the ALC continues to work towards forging stronger collective change across ecosystem groups to deepen the belief that the realisation of and coming together on common ground and space will lead to more sustainable and impactful benefit to all players.

NOTE

- Institute for Adult Learning. “Adult Learning Collaboratory.” https://www.ial.edu.sg/about-ial/ourcentres/ adult-learning-collaboratory-alc

Not Just Coordination but Collaboration

To better nurture the ecosystem, we may have to ask ourselves how to both coordinate and collaborate better across the CET ecosystem. To date, the overall lead and primary coordinators of the movement has been the government. They have done well in co-opting and marshalling the other ecosystem players as much as possible through inventive, relevant and generous schemes and policies.

However, it is not yet a fully level playing field. For instance, while more than 24,000 employers (about 22,800 from SMEs) have sent their workers to SkillsFuture-supported programmes,4 they constitute only about 7% of the 354,000 SMEs that account for the bulk of enterprises in Singapore.5 Inroads with SMEs have been made, such as with its SkillsFuture Queen Bee initiative of a community of enterprises supporting one another.6 Many SMEs do also incorporate workplace learning programmes and in-house initiatives for their workforce. But more can be done to bring these employers on board.

Might there, for instance, be ways to organically replicate SkillsFuture Queen Bee arrangements and benefits, were a public agency such as Enterprise Singapore to act as an ecosystem coordinator to drive synergies across sectors and enterprises? When there is conscious coordination across a sector, all players could come together to assess its skills stock and levels, build towards thoughtful job designs and allow for more workers to use and grow complex skills to benefit the entire sector. SMEs in particular could benefit from such arrangements as they are buoyed by the sector coming together rather than an anointed queen bee who focuses only on their immediate supply chain partners, for example. Information flow for SkillsFuture messaging could also be enhanced to better reach and persuade a wider and more inclusive spread of employers and enterprises.

Different learning providers have few opportunities to overlap or meet, with collaboration being a rare occurrence and active competition among them being the norm.

Behaviour in an ecosystem, and ultimately its long-term health, is affected by the rules of engagement and the nature of standards and interfaces — open versus closed; imposed versus emergent.7 This is where there is a meaningful difference between coordination and collaboration. While we are adept at coordinating large segments of the skills ecosystem to work together in an organised way, we do not yet see many true instances of deep collaboration, where different players work organically together to achieve something more than they otherwise could by themselves.

For example, what if the IHLs, private sector training providers and corporate training entities, as well as their cadre of trainers and educators, were to come together to create better quality learning? Today, these different learning providers have few opportunities to overlap or meet, with collaboration being a rare occurrence and active competition among them being the norm. How might we create conditions where they could instead collaborate — for mutual benefit, as well as for the good of the ecosystem as a whole?

The Place of Private Sector Learning Providers in the CET Ecosystem

Although private sector providers might be expected to be entrepreneurial enough to thrive on their own in the learning marketplace, there are benefits to nurturing and involving them as part of a broader national effort.

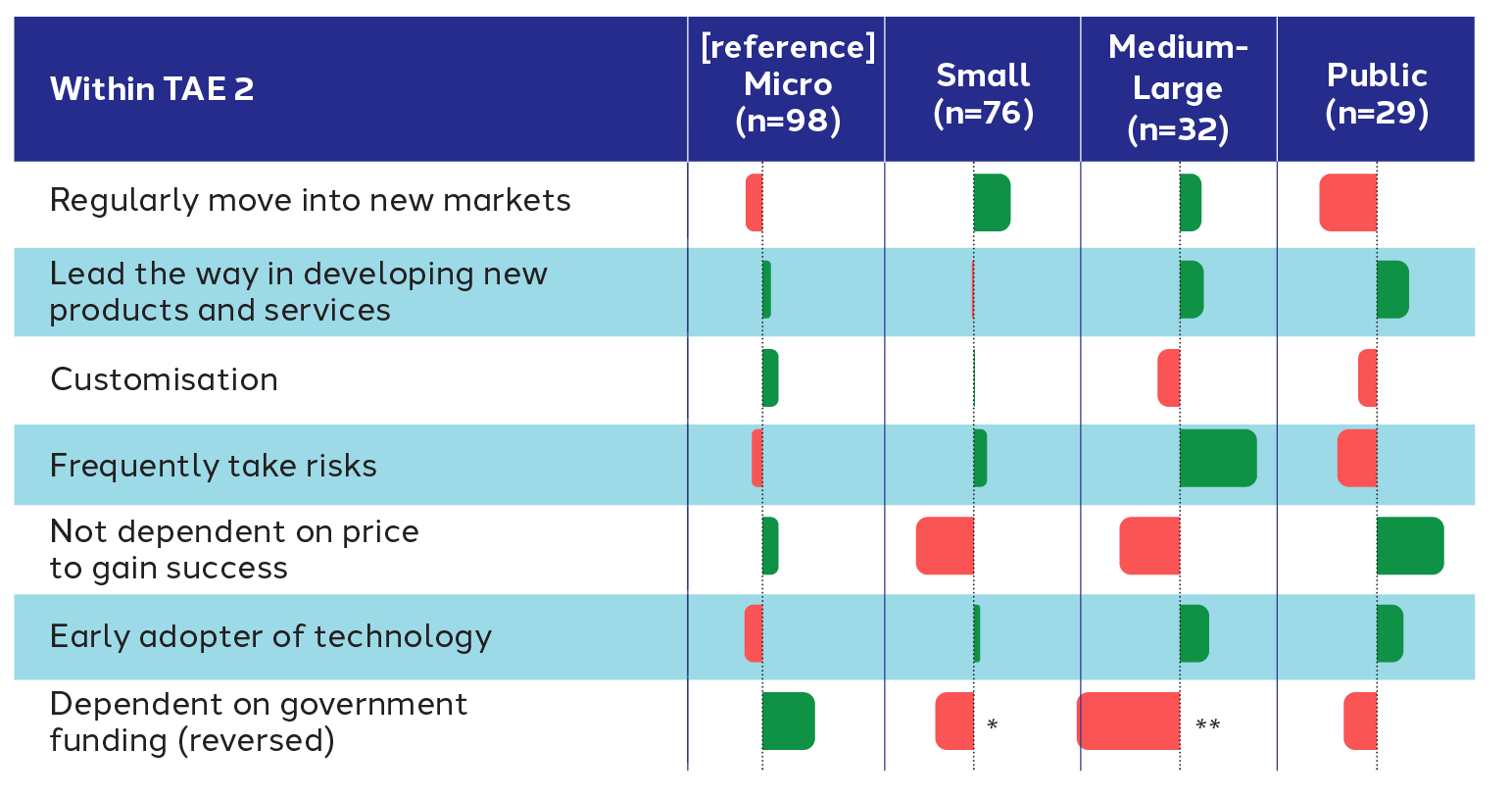

An Institute for Adult Learning (IAL) study on the Training and Adult Education (TAE) landscape8 shows that private sector providers, particularly those of small and medium-large sizes, move more regularly into new markets, more frequently take risks, and are more readily adopting new technology — compared with their public sector counterparts such as IHLs. Case studies in the research also suggest private sector training providers are a key source of dynamism and innovation in the TAE space — an important aspect of the skills ecosystem.9

Private sector providers may furthermore play an outsized role in Singapore's economy if they have moved into business consultancy work, where they are in a position to help companies integrate learning, jobs and skills within the flow of work — in effect setting the tone and tenor for the rest to emulate.

Whilst IHLs will always have a specialised place in particular industries, private sector training providers have a distinct industrial impact and reach. How then can we meaningfully nurture all entities to enhance the skills ecosystem as a whole?

One instance where we do see some measure of holistic collaborative effort is in the recent push for Career Health, which reached out simultaneously to employers, enterprises and individuals alike. The initiative was spearheaded by the lead public agencies, SkillsFuture Singapore and Workforce Singapore, with other key players such as the Institute for Human Resource Professionals and the Employability and Employment Institute.

This is not to say greater public sector intervention is the only way to go. Instead, we need to find further ways for all players, especially those from the broader private sector, to be more meaningfully engaged and included in sector and ecosystem developments. When the ground is more level, the likelihood of collaboration, where the aspiration is for the whole to be greater than the sum of its parts, can be fulfilled.

We need to find further ways for all players, especially those from the broader private sector, to be more meaningfully engaged and included in sector and ecosystem developments.

Another important group of stakeholders to consider is the learners: the purpose for the ecosystem's existence in the first place. From the start, the SkillsFuture movement has placed significant emphasis on easing access to learning and growth opportunities. There has been promising growth in learner participation: in 2024 alone, 555,000 individuals took on SkillsFuture-supported programmes, a 6% increase from the previous year.11

Nevertheless, there may be segments of learners who have yet to come on board. These may include gig workers and freelancers who lack industry or organisational support to guide them to appropriate learning activities and provisions. A sizeable proportion of Singaporean adults may also lack the basic literacy, numeracy and adaptive skills to keep up with the current or future demands of a rapidly changing marketplace12 — they may be unable, rather than unwilling, to skill up enough. Addressing such gaps — together with the learners themselves —would be vital to strengthening the CET ecosystem.

Three Strategies for a Healthier CET Ecosystem

Activating Singapore's skills ecosystem more effectively, incorporating both coordination and collaboration efforts, remains a challenging task — but it is vital to achieve the movement's broader outcomes. This may involve a number of strategies going forward:

Recognise the diversity, scale and spread of the CET ecosystem

The more ready we are to leverage on the organic opportunities that this multi-faceted ecosystem, with its many complementarities, can bring us, the better we can ensure value capture for the ecosystem, its players and the workforce who are the beneficiaries. To do so, we must seek deliberately to be more inclusive and consultative, beyond our traditional comfort zones. We must clarify connections between learning, work and progress. And we must embrace the understanding that everyone has to contribute to the ecosystem, in order to achieve more together through intentional collaboration and the integration of resources, efforts and initiatives.

Ensure that players fully understand their relative roles and value in the ecosystem

This involves both multi-party communication approaches as well as targeted outreach with particular branches of the ecosystem to fully prepare them to play their roles. For example, we may want to engage IHLs and private sector training providers together, so that each can do what they do best — while they all do better by being aware of what each other is doing. The ecosystem must be kept informed about the different key nodes of the SkillsFuture web of activities and each player's role in it: from the groups who will function as first responders in skills gap recognition and delivery, to those who will ensure that the skills are meaningfully deployed in the workplace where they are needed. The ecosystem can then work out how best to engender more organic ecosystem autonomy towards mutual benefit and shared goals.

Lead by focusing on each player group while also holding the rest of the ecosystem in mind

Complementarities can be best exploited if this dual attention is paid both to the specific players involved and to the ecosystem as a whole. Enterprises may be the right target for initiatives that leverage learning in the flow of work, but because they are such a diverse group, it may help to heighten their awareness of prevailing trends and the broader ecosystem.

How then do we acknowledge the complex intermesh of ecosystem players who range from the large to the small, from enterprises to providers and from educators to learners? We may need to engage with each ecosystem player group at a deeper level, through deliberate user profiling for example, to capture each user group's particular needs. With such data and understandings, strategic plan-making across the whole ecosystem could then be nuanced and communicated via ecosystem-wide narratives. Complexity is then welcomed and embraced: rather than dodged or deconstructed for the ease of managing each group separately, which could lead to silos that defeat ecosystem benefits.

Conclusion

The CET ecosystem built up and cultivated over the last decade and more has reached a certain level of maturity and value that is yielding benefits for Singapore.

Public service agencies could better steward the CET ecosystem by honing their coordination and collaboration efforts across the various agencies and ministries. This would entail each agency going beyond its particular mission to converge on the larger CET ecosystem vision for Singapore. There would also need to be nimbleness and agility within such efforts to take on emergent situations should economic headwinds and turbulence dictate the need for rapid pivoting. With deep understanding and nurturing of the ecosystem and more organic and inclusive approaches in place, the CET ecosystem across the next decade could reap even more benefits for Singapore.

NOTES

- Prime Minister's Office. "PM Lawrence Wong at the SkillsFuture 10th Anniversary." https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/PM-Lawrence-Wong-at-the-SkillsFuture-10th-Anniversary

- Adner, R. (2016). Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy: An Actionable Construct for Strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316678451 (Original work published 2017)

- La JJ, Li M and Liu X (2024) The application of innovative ecosystems to build resilient communities in response to major public health events. Front. Public Health. 12:1348718. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1348718

- The Straits Times. "More people tap SkillsFuture programmes in 2024 amid stronger support for mid-career workers." https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/more-people-tap-skillsfuture-programmes-in-2024-amid-stronger-support-for-mid-career-workers

- Data.gov.sg "Enterprise Landscape By SMEs And Non-SMEs, Annual." https://data.gov.sg/datasets/d_f9c93c1ffcefe660272c101cd733711c/view?dataExplorerPage=1

- SkillsFuture Singapore. "SkillsFuture Queen Bee Initiative." https://www.ssg.gov.sg/newsroom/skillsfuture-queen-bee-initiative-strengthens-the-role-of-industry-leaders-in-building-capabilities-of-workforce-and-enterprises

- Jacobides MG, Cennamo C, Gawer A. Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strat Mgmt J. 2018; 39: 2255–2276. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2904

- Institute for Adult Learning. "Training and Adult Education Landscape." https://www.ial.edu.sg/research/our-research/training-and-adult-education-(tae)-landscape-2

- Institute for Adult Learning. "Dynamic Capabilities." https://www.ial.edu.sg/research/our-research-publication/dynamic-capabilities

- Refer to Note 8

- Refer to Note 4

- The OECD's Programme of International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) has indicated that, relative to peer countries, 30% of Singapore's adults (OECD average: 26%) had low literacy; 22% of Singapore's adults (OECD average: 25%) had low numeracy; 29% of Singapore's adults (OECD average: 29%) had low proficiency in adaptive problem solving. See: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/survey-of-adults-skills-2023-country-notes_ab4f6b8c-en/singapore_382e963a-en.html