Social Norm Nudges and Social Sensemaking: Lessons for Policymakers

ETHOS Issue 26, Dec 2023

What is social sensemaking and why does it matter?

Behavioural nudging is a popular tool for policymakers, but research suggests that social sensemaking may reduce their effectiveness.1 Social sensemaking is when individuals try to infer the intent behind the choice architect's decision and what their decision would signal to the choice architect and/or other people around them. This can forestall the automatic cognitive biases that make nudges effective. In some cases, questioning the motives of the choice architect can even lead to backfiring on the intended outcome of the nudge.

A BACKFIRED NUDGE

In 2016, the Dutch government—encouraged by the success of opt-out organ donation systems in many countries where residents are automatically considered organ donors unless they explicitly state their non-consent—passed a bill to switch their organ donation system from an opt-in to an opt-out scheme.

However, unlike in other countries, this change resulted in a 40-times increase of opt-out requests in the Netherlands. This dramatic jump in active rejections occurred not only among newly registered donors but also among those who had previously consented to donate but now deliberately revoked their consent. One explanation for this backlash is that some Dutch residents may have interpreted the change in choice architecture as an attempt by the government to limit their freedom of choice, prompting them to explicitly exercise their opt-outs in protest.1

NOTE

- J. M. T. Krijnen, D. Tannenbaum, and C. R. Fox, (2017). “Choice Architecture 2.0: Behavioral Policy as an Implicit Social Interaction”, Behavioral Science & Policy 3, no. 2 (2017): 1–18.

Nevertheless, some behavioural researchers argue that social sensemaking, when used correctly, can increase the effectiveness of nudges.2 They cite the example of defaults, which always reveal the intent of the choice architect, yet are one of the most effective nudges available in most contexts.

In considering nudges as policy tool options, policymakers in Singapore should understand how social sense-making works in our context, since it could influence how citizens react to such measures.

A study of social norm nudges and social sensemaking in Singapore

A recent study by a Civil Service College (CSC) team has examined social sensemaking and its effect on social norm nudges, a common intervention used by public agencies in Singapore.

In late 2021, CSC, with support from the Central Provident Fund Board, the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment, the National Environment Agency, and the Ministry of Health, conducted an online survey with 2,000 Singapore citizens and permanent residents, aged 21 and above. The survey aimed to identify whether individuals engage in social sensemaking when presented with social nudges for health, environment, and finance public policies. In addition, the study also sought to understand the factors that can trigger social sensemaking and influence the effectiveness of social norm nudges in these policy domains.

In the survey, each participant was presented with five hypothetical scenarios to do with:

| Central Provident Fund (CPF) top-up | |

| CPF refund used for housing | |

| Buying locally produced vegetables | |

| Bring your own bag for grocery shopping | |

| Long-term health insurance scheme |

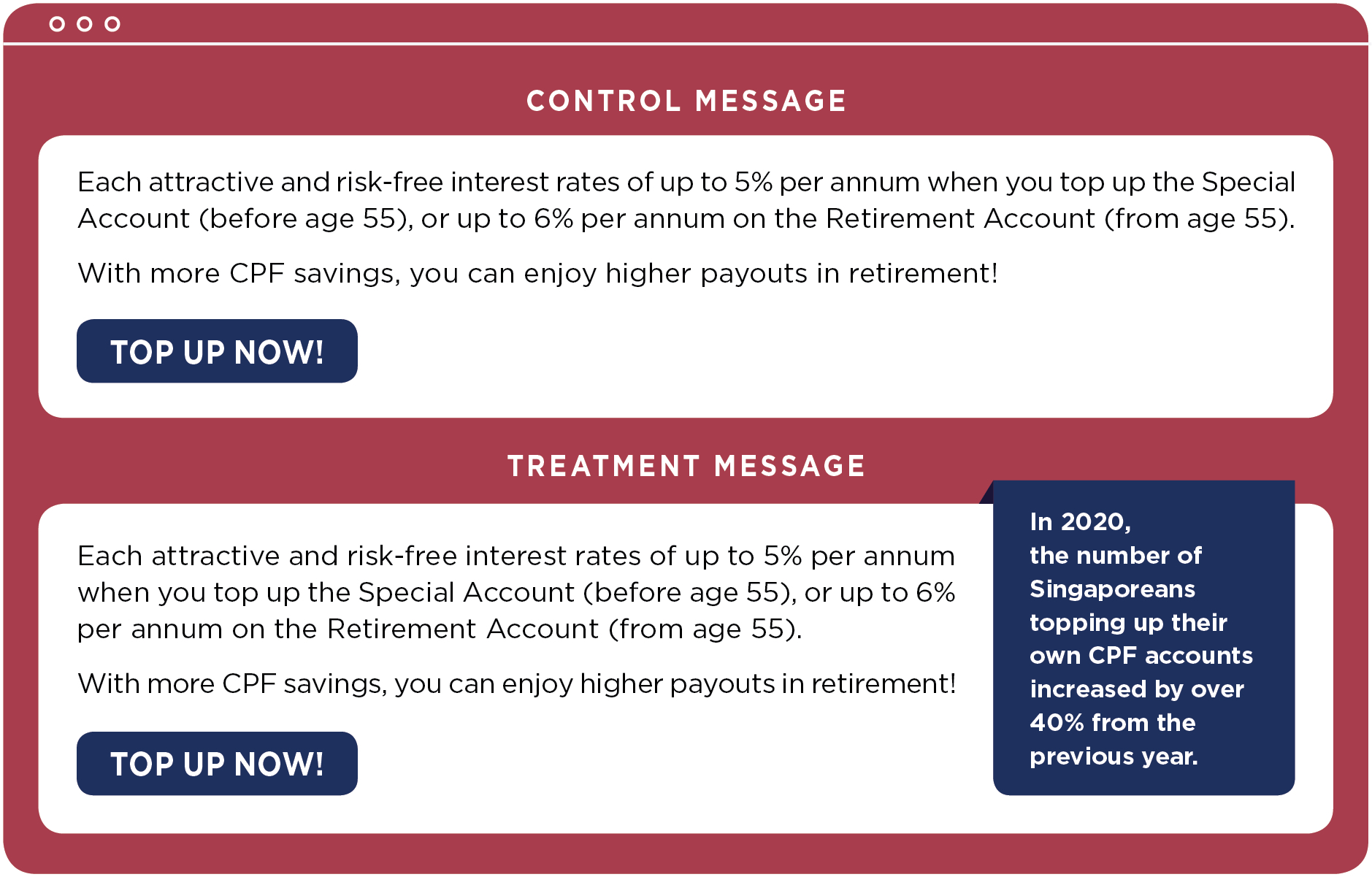

The scenarios were presented in a random sequence. For each scenario, participants were randomly shown either the control or treatment message. All treatment messages contained a social norm nudge (see Figure 1).

EXAMPLE - SCENARIO 1

TOP UP TO CPF SPECIAL ACCOUNT OR RETIREMENT ACCOUNT

A social norm nudge was added to all treatment letters.

After viewing the message, participants were asked to indicate their intended decision and answer ten questions on factors that might have influenced their social sensemaking and decision-making. These questions were designed to tease out information about participants’ ease, importance, and certainty of their decisions, as well as their trust in the choice architect, who in this case was the government.

Additionally, these questions also asked about aspects of social sensemaking: specifically, if the participants thought of the government’s intentions as well as other people’s decisions when they made their decision, as well as if they were concerned how the government and other people around them would perceive their own decision.

These questions were intended to shed light on factors that might have affected their decision-making as well as to show if social sensemaking had been triggered.

What did the study find? Lessons for policymakers

1. Social norm nudges alone do not work. Instead, people are influenced by the importance of the decision and trust in the government.

The study found that social norm nudges had no statistically significant impact on the respondents’ intended decisions for four out of the five scenarios. For the scenario on buying local vegetables, the treatment message with social norm performed statistically worse than the control message.3 Instead, we found that participants’ decisions were influenced by the perceived importance of their decision, if they agreed with the government’s intention, and whether they believed that the government was more likely to succeed in their policy objective.

Policymakers may achieve greater results by helping citizens understand the importance of their decision as well as increasing their trust in government agencies.

These results suggest policymakers should avoid relying solely on social norm nudges to elicit behavioural change. Instead, we could consider using other nudges in combination to trigger a stronger positive response. Additionally, policymakers may achieve greater results by helping citizens understand the importance of their decision as well as increasing their trust in government agencies. Public agencies could do this by being more transparent about the intention of the policy and communicate clearly with the public about the reasoning behind policy decisions.

2. Social sensemaking made very little impact, at least in the online environment.

Based on the results of this study, respondents engaged in some degree of social sensemaking, but it was not consistent across all scenarios. They only thought sporadically about the government’s intentions, other people’s decisions, and if they were concerned about how the government and other people would perceive their decisions. In addition, these factors seemed to have only a small effect on people’s decision-making. Hence, there may be little practical value for policymakers to specifically target social sensemaking for behavioural change. It is worth noting that the online environment of the study could have contributed to the small effect of social sensemaking as respondents made decisions in their own environment alone. Social sensemaking may have a greater impact in a physical environment where decisions are more public and hence people might be more concerned about what others think of their choices.

Social sensemaking may have a greater impact in a physical environment where decisions are more public.

3. Framing of benefits and costs of policies in public communications is essential.

From the qualitative responses, the study found that another important factor that played a role in respondents’ decision-making in all scenarios was how they perceived the costs and benefits of the policy to both themselves as well as to the whole society. Hence, policymakers may get more buy-in from the public by highlighting and better framing the personal as well as societal costs and benefits of certain policies. By changing how the costs and benefits are communicated to citizens, policymakers may be able to sway people’s perceptions of the policy.

Policymakers may get more buy-in from the public by highlighting and better framing the personal as well as societal costs and benefits of certain policies.

4. The importance of testing potential policy interventions.

This study highlights the importance of testing potential policy interventions for specific contexts. Some limitations of the study were that it was conducted as an online survey, conducted in only English and with a sample that was underrepresented for certain demographics. Hence, the findings might not be generalisable to the behaviours and decision-making considerations of the general population. In addition, the study relied on self-reported answers, which might not accurately reflect actual behaviours in real life.

The study’s findings were unexpected, as social norm nudges have long been held as an effective nudge for behavioural change. However, this study showed that in the scenarios tested, social norm nudges alone as well as social sensemaking had very limited effect on people's decision-making and could even have backfired in the local produce scenario (see scenario 3 for buying locally produced vegetables). What the study did highlight is the importance of testing out potential policy interventions for specific contexts to better understand their effects before introducing them to the public.

Testing out potential policy interventions for specific contexts to better understand their effects before introducing them to the public.

This is a summary of a research project done by Do Hoang Van Khanh and Charmaine Lim. For the full research report “Social Sensemaking in Public Policies”, please access https://www.learn.gov.sg/d2l/home#/course/400886?app=dlp.

NOTES

- J. M. T. Krijnen, D. Tannenbaum, and C. R. Fox, “Choice Architecture 2.0: Behavioral Policy as an Implicit Social Interaction”, Behavioral Science & Policy 3, no. 2 (2017): 1–18, https://www.google.com/search?q=Krijnen%2C+Tannenbaum+%26+Fox+2017&oq=Krijnen%2C+Tannenbaum+%26+Fox+2017&aqs=chrome..69i57.598j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

- R. H.Thaler, and C. R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008).

- The treatment message used for scenario 3 was different than those of other scenarios. Specifically, the messages for other scenarios added a social norm nudge on top of the message used in the control message, but scenario's 3 treatment message only included a social norm alone. Thus, the results of scenario 3 is not comparable to other scenarios.