Encouraging Healthier Choices: Helping People Take Better Care of Themselves

ETHOS Issue 26, Nov 2023

It is clear that in Singapore, as with health systems around the world, we can no longer afford to keep focusing healthcare on treating those who are ill; we have to shift focus upstream and help people make healthier choices in their daily lives. This is why Healthier SG’s increased focus on prevention and healthier living is an encouraging and exciting development. We believe that behavioural approaches will be key to achieving this shift at individual, community, service, and system levels.

We know from the evidence and our own everyday experiences that there is often a chasm between what people know they should do, what they intend to do, and what they actually do in practice. In behavioural science, this is called the ‘intention-action gap’. This gap is particularly pronounced where the reward for present action is only experienced in the future, which is clearly the case for many preventative health behaviours. I will not immediately lose weight if I reject a delicious dessert, nor will I instantaneously get healthier after attending a regular screening: the benefits will be felt only in the months and years to come.

Hal Hershfield’s recent book, Our Future Self, sets out the mental biases we commonly experience when thinking about the future.1

He argues that we tend to view the future as a distant possibility, and our future selves seem like strangers. Consequently, we often opt for more immediate gratification, which disregards or discounts our future health and wellbeing. Thankfully, Hershfield highlights the science behind these decisions and provides practical tips on how we can better connect with our future selves—balancing living for today and planning for tomorrow.

For example, there are people in our lives towards whom we act more generously and virtuously: people like our children, our parents, and our closest friends. Therefore, when it comes to preventative health behaviours, if we think about our future selves as if they are people we are close to, we may be more likely to take positive actions. This ‘future self’ approach is something we believe that health practitioners and family GPs could draw on in their sessions with Singaporeans. While working on a care plan together, doctors could help patients develop greater connections to their future selves in order to make better health decisions today.

However, we cannot rely solely on individuals and conversations with doctors to turn the tide. If we want to support preventive approaches and help people to live more healthily, behavioural science shows that we need to pull a number of systemic levers to change the environments in which people make these decisions.

Behavioural science shows that we need to pull a number of systemic levers to change the environments in which people make decisions.

Nudging upstream as well as downstream

One area of prevention in which upstream interventions have been explored is tackling obesity. The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) and our sister organisation, Nesta, are undertaking a major programme of work that seeks to help redesign food systems. Behavioural approaches have often focused on downstream changes, for example, by encouraging people to eat more healthily through information on calories and public education campaigns. However, we believe that this must be complemented by a much stronger focus on upstream changes, such as by shifting the behaviour of businesses and regulators. This includes everything from product reformulation to the changing landscape of how we all consume food in supermarkets, online, via delivery apps, and so on.

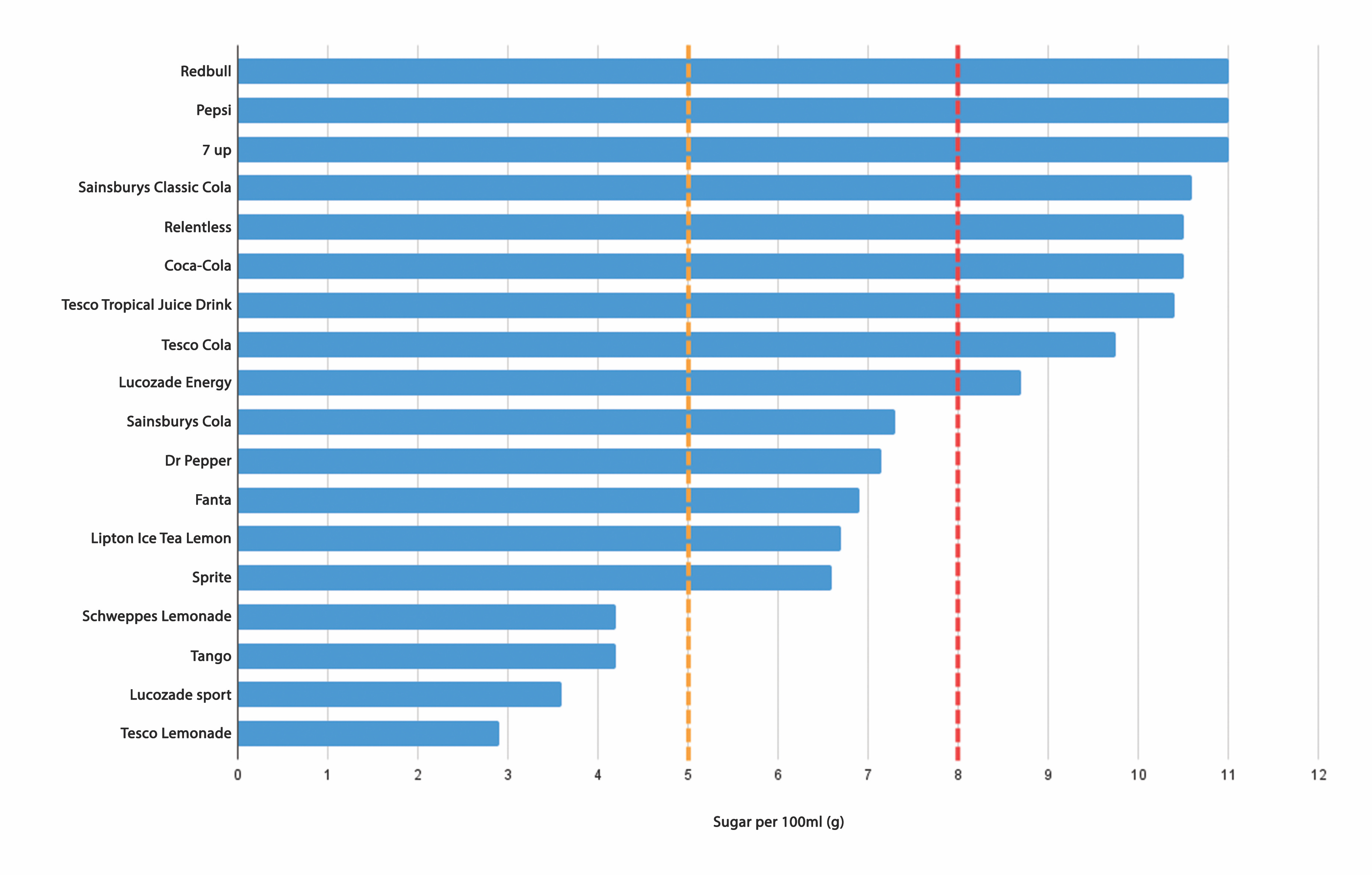

A prominent example of an upstream intervention that continues to reap benefits is the UK’s sugar sweetened beverage levy.2 We often describe this as a 'double nudge'—since while it was intended to shift consumer behaviour towards less sugary drinks, it was also explicitly designed to shift the behaviours of manufacturers and retailers. The levy was first announced in 2016 and two of its design features are important to flag. First, the levy would not come into force until April 2018, meaning that producers had two years to make changes to their drinks. Second, the levy was divided into two tiers: drinks with more than 8 g of sugar per 100 ml would face a higher levy than those with more than 5 g of sugar (see Figure 1).

These tiers meant producers had a clear incentive to reformulate their products to avoid higher levies. Eight months after the announcement and more than a year before the levy came into effect, major beverage companies announced that they were reformulating their drinks so that they were exempt from the levy.3 In other words, consumers benefited from this intervention without changing their behaviour and purchasing decisions. The levy had successfully nudged providers to reduce sugar in their drinks; this system change was doing the heavy lifting rather than individuals.

In Singapore, efforts such as the Nutri-Grade initiative are setting similar goals;4 Nutri-Grade hopes to spur companies to reformulate their products by reducing sugar content. Following the announcement of the measures in 2020, the median sugar level of pre-packaged beverages fell from around 7% to 4% the following year. The Health Promotion Board is hoping to build on this momentum by working with food and beverage operators to make kopi 'siew dai' (with less sugar) the default for local coffee orders. This would mean that, like the UK sugar sweetened beverage levy, individuals are supported to make healthier choices by changes to the choice architecture of the food system.

Similar approaches can also be applied to growing online environments.5 The pandemic has led to a huge uptick in the use of food delivery apps, which presents an opportunity to influence the design of these online platforms to help people make healthier decisions. BIT’s online studies have demonstrated that repositioning lower energy options more prominently has the potential to encourage lower energy food choices in online delivery platforms.

Aligning incentives and interventions

Our research has shown that these types of healthy nudges can be implemented within a sustainable business model. We believe that the economic impacts of these upstream nudges are critical to understand and address. For example, BIT Australia worked with the Alfred Hospital and VicHealth, on trials to explore the impact of reducing the visibility and increasing the cost of sugary drinks in hospital canteens and vending machines.6 Retailers were understandably worried that these interventions would decrease their overall sales, but in fact, our trials demonstrated that this was not the case in practice. Consumers did not stop purchasing drinks altogether but shifted from purchasing sugary ‘red’ drinks to buying healthier ‘amber’ and ‘green’ drinks. Highlighting that these interventions do not hurt retailers’ bottom line is critical to scaling the uptake of these approaches.

Another approach to engage and align incentives with retailers is through signifiers like health ratings. If there is competition and comparison between retailers and delivery platforms in terms of healthier ratings, then there is an incentive for them to shift towards healthier options to improve their market positioning.

However, where there is evidence of misalignment between profits and public health objectives, we need to use harder levers, such as regulations. For instance, in Singapore and many countries around the world, we know that unhealthy snacks and sweets are often positioned at retail checkouts. These impulsive food purchases are money spinners for retailers, so the economic and health objectives are clearly misaligned. In October 2022, the Department of Health and Social Care in the UK set limits on where unhealthy food can be placed in shops. These restrictions directed that products high in fat, salt, or sugar can no longer be displayed in prominent locations such as at store entrances, aisle ends, and checkouts. The rules apply to equivalent high-traffic spots on food shopping websites. At BIT, we are supportive of these types of regulatory interventions and continue to run trials and collect evidence to explore how we can work together with industry when incentives align and how to intervene when they do not.

Healthy nudges can be implemented within a sustainable business model.

Harnessing tech to encourage healthier choices

There has been much discussion about the role of technology in supporting healthier choices. Over the past decade, we have seen an explosion of apps: food apps, health apps, vaccine apps, travel apps, payment apps and so on. For service delivery organisations, it can often feel like we need to have an app as part of our armoury. But for those working in public health and policy more widely, it is worth recognising that the vast majority of apps are not actually successful, and indeed, many seem like a solution looking for a problem. We often get asked how to increase the uptake of a particular app, but the first question we generally ask is whether an app is the right solution in that particular space. If it is indeed a viable channel, given the heated competition for consumers’ attention, we have to ensure that it is carefully designed to meet users’ needs. So we work with partners to test different communication strategies to increase engagement and, perhaps most importantly, evaluate their impact on desired health objectives.7

Technology solutions go beyond apps, of course. For instance, good old-fashioned text or SMS message reminders can be effective at encouraging attendance and engagement with health interventions, especially as messaging systems enable these prompts to become more tailored. In the past, we might have had to send the same text message encouraging people to attend their medical appointments to all recipients. Today, it is much easier to make these messages much more personalised. For instance, we can provide specific details like individual names, dates, clinics' addresses and directions from home. Such simple but effective messaging has been shown to be highly effective nudges for tasks such as vaccinations and follow-ups for boosters.

Simple but effective messaging has been shown to be highly effective nudges.

Chatbots have also shown effectiveness in increasing attendance and uptake. AI-powered healthcare chatbots can now handle simple inquiries with ease and provide a convenient way for users to research information. In many cases, these self-service tools are also a more personal way of interacting with healthcare services than browsing a website or communicating with an outsourced call centre. In fact, according to Salesforce, 86% of customers would rather get answers from a chatbot than fill out a website form.

One notable area that has benefited from the advent of chatbots is mental health management. Healthcare chatbots can provide mental health assistance 24/7. This can be critical to those living in rural areas where mental health resources are scarce or for people experiencing a crisis in the middle of the night when 'human help' is not available. For example, a chatbot could quickly:

- Offer self-help tips like meditation, relaxation exercises, and positive affirmations.

- Connect people with mental health experts who can help them with specific challenges related to living with a mental illness.

- Connect patients with other people who are going through similar struggles, offering peer support and a community.

Technology may also help us to better connect with our future selves. If GPs were to take up Hershfield’s recommendation to help people make a stronger connection with their future selves, they may, for instance, be able to draw on apps that enable us to create ‘filters’ that visibly age us, often realistically. Obviously, there will be a delicate balance to be struck about how these tools and data should be used, but we see opportunities to work with GPs on how they can harness the power of technology to help people make healthier choices. For example, the research of Susan Jebb has highlighted that technology can make it easier for GPs to bring up, address and monitor sensitive issues like obesity and loneliness.8

Beyond mass messaging: personalisation and targeting

Governments around the world often rely on running mass information campaigns to raise health awareness. While these mass efforts have their place in promoting health behaviours, too many campaigns are run without being tested for effectiveness (particularly in terms of actual behaviour change rather than engagement metrics) or an assessment of return on investment. As with many organisations, the pandemic spurred methodological advancements at BIT in terms of our ability to test communications online at speed and scale. For instance, we can now test different campaign messaging through online experiments with panels of people in matters of days, rather than weeks or months.

While there is a role for mass campaigns, we believe we need to shift away from trying to target the entire population at once to thinking more deeply about personalisation and targeting. How do we get the right messages to the right people at the right time, rather than always to the largest number of people?

We also need to combine these campaigns with service delivery. In Healthier SG, as we move to pair each household with a GP practice, we can consider how to leverage this relationship to individualise health messaging. By designing good care plan templates, we can help all GPs have targeted discussions with their patients about the kind of tailored solutions that will work best for them.

It is important to note while we underline the importance of personalisation, this does not automatically mean individualisation. People’s decisions are often strongly shaped by their social context and group dynamics. For instance, we saw through the pandemic that social networks were extremely powerful in influencing vaccination behaviours—messages about protecting your family and community were more effective for many people than simply reminding them about vaccinating to protect their own health. As such, we believe that a huge driver of positive health outcomes will be one’s immediate family. As GPs implement care plans with their patients, how you personalise that by household and how you engage next-of-kin in conversations becomes very important as well.

Exploring the next frontier of health behaviours and choices

A few things continue to animate discussion in the “What next in health behaviours?” space:

- As we consider the behaviours of individuals in response to various types of levers, we must also consider the context within which these interactions are taking place, i.e., the healthcare institutions themselves. Health delivery systems are an area of huge interest in Singapore and across the world. In the UK, BIT is doing critical work on redistributing hospital load and demand,1 which may well have resonance for Singapore. We are also exploring the evidence on organisational behaviour and systems to tackle productivity issues, such as how we get health staff to procure more effectively and how we attract and retain health professionals.

- From a cohort perspective, we are expanding our attention on ageing. For example, we are undertaking exciting work with the UK’s Centre for Ageing Better that looks at debiasing recruitment of older workers. This is an area that should also be of interest in Singapore in terms of how we can help our seniors continue to live productive and fulfilling lives in later life. More broadly, we are asking how we might shift from talking about ageing to talking about longevity.

- Adjacent to health but very much associated with longer term wellbeing is food sustainability. One of the lessons Singapore learned from COVID is how vulnerable we are to disruptions in the global food supply chain. The Singapore Food Agency has announced that as part of the Singapore Green Plan 2030, Singapore will build up our agri-food industry’s capability and capacity to sustainably produce 30% of our nutritional needs by 2030. Behavioural Insights could help shape the design of incentives, markets, and platforms around this—from the food production angle and/or to raise consumer acceptance (e.g., of plant-based protein).

Personalisation does not automatically mean individualisation. People's decisions are often strongly shaped by their social context and group dynamics.

As we approach a decade of applying behavioural insights in Singapore, behavioural tools become more critical than ever to help us make the right decisions in order to live healthier lives. But we should not limit ourselves to focusing on individual behaviours and mass campaigns: behavioural levers can help us redesign our health systems and environments, working closely with industry, regulators, GPs and communities whilst unlocking the potential of technology. And this should be done with an experimental, iterative and human-centred mindset. If we do this, we may better achieve the exciting ambitions set out in Healthier SG.

NOTES

- Hal Herschfield, Your Future Self: How to Make Tomorrow Better Today (Little Brown Spark, 2023), https://www.halhershfield.com/yourfutureself.

- Tom Sasse and Sophie Metcalfe, “Sugar Tax”, Institute for Government, November 14, 2022, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/explainer/sugar-tax.

- Michael Hallsworth, “The Soft Drinks Levy Is Working before It Has Even Been Applied”, The Behavioural Insights Team, November 11, 2016, https://www.bi.team/blogs/the-soft-drinks-levy-is-working-before-it-has-even-been-applied/.

- Lee Li Ying, “‘Siew Dai’ Could Be Default Option for Your Morning Kopi or Teh”, The Straits Times, September 27, 2023, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/siew-dai-could-be-default-option-for-your-morning-kopi-or-teh.

- Filippo B., Jovita L., Filip M., James, F., Abigail M., and Hugo H., “The Impact of Altering Restaurant and Menu Option Position on Food Selected from an Experimental Food Delivery Platform: A Randomised Controlled Trial”, The Behavioural Insights Team, May 19, 2023, https://www.bi.team/publications/the-impact-of-altering-restaurant-and-menu-option-position-on-food-selected-from-an-experimental-food-delivery-platform-a-randomised-controlled-trial/.

- Healthy Eating Advisory Service, “Alfred Health—Sugary Drinks Trials”, March, 2023, https://heas. health.vic.gov.au/case-studies/alfred-health-sugary-drink-trials/.

- Helen B., Jovita L., Giulia T., and Morgan G., “Beyond Tech: The Role of Behavioural Science in Digital Health Apps”, The Behavioural Insights Team, June 27, 2016, https://www.bi.team/blogs/beyond-tech-the-role-of-behavioural-science-in-digital-health-apps/.

- Susan Jebb, “Knowledge, Nudge and Nanny: Opportunities to Improve the Nation's Diet”, March 17, 2015, https://www.ox.ac.uk/research/research-in-conversation/healthy-body-healthy-mind/susan-jebb.