Economising with Imagination in Harsh Times

ETHOS Issue 25, April 2023

There is much debate globally about how the accumulation of crises—economic, ecological, political and around energy—now amount to a polycrisis. Whether or not they are as connected as some believe, there is no doubting the pressure they are putting on public services across the world. Governments generally responded well to the COVID-19 pandemic, showing great agility. But one legacy of the pandemic is fiscal overstretch—and sharp constraints on resources which make it even harder to respond to the new crises. Meanwhile geopolitical pressures are pushing up spending on defence, which means even less resources available for other purposes.

So can governments adapt, and refashion their shape, processes and cultures to more turbulent times—the times that Xi Jinping often describes as “changes unseen in a century”?

Governing in booms is very different from governing in times of retreat. In this different context, governments need to think and act to use resources carefully while also addressing deep-seated problems. Here, useful ideas can be drawn from ecology, which has introduced many to the idea that policies of reduction—whether reducing energy and materials use, waste or carbon emissions—can be as important as policies for growth.

I propose three areas in which new methods are needed:

- We need to mobilise intelligence more systematically, i.e., data, evidence and knowledge of all kinds, to ensure that action is focused, targeted and smart. Experiences from the pandemic can be applied to other fields but will require different structures and processes to be effective.

- Some overdue reforms to public finance are needed to better fit the demands of the 21st century, including using investment methods for human services such as education, health and innovation, and better use of data to connect inputs of money to outputs and outcomes.

- We need a framework for thinking creatively about how to achieve economies within public services: going beyond the standard tools of cuts, trimming and delay to more creative options for restructuring services and changing the contract with citizens.

Intelligence as a Core Task of Government

Governments have always relied on intelligence to do their work. But whereas in the past this was thought about primarily in relation to enemies and threats, espionage and war, they now need to think systematically about intelligence1 in relation to everyday tasks, from transport to healthcare, welfare to education

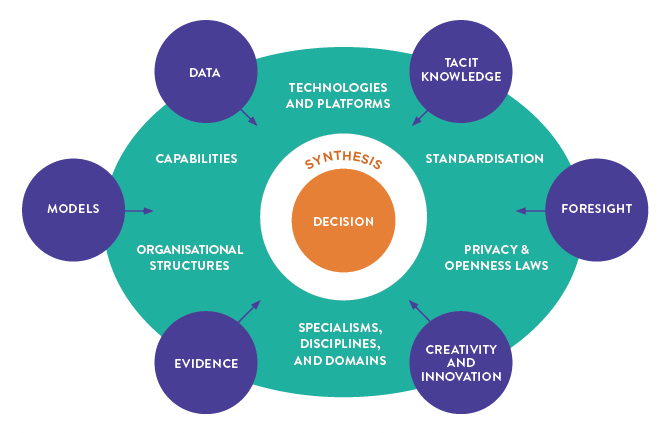

This became very apparent during the pandemic. As I showed in a recent study of how governments—and the societies around them—mobilised intelligence to handle the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects, the last few years brought an explosion of innovation in new ways to organise intelligence. The pandemic was an unprecedented event in its global impacts and in the scale of government responses and required a myriad of policy decisions: about testing, lockdowns, masks, school closures, visiting rules at care homes and vaccinations. All of these depended on inputs of intelligence including data, evidence, models, tacit knowledge, foresight, and creativity and innovation.

Improvising Intelligence to Tackle a Healthcare Crisis

During the pandemic, Taiwan’s ‘Digital Fencing System’ monitored locations based on triangulating a phone’s position relative to nearby telephone masts.

Monitoring was conducted by telecoms companies using phone numbers of quarantining individuals provided by the government, and with protections on privacy including a constitutional limit of 14 days on tracking any individual.

But governments varied greatly in their ability to organise these well. Governments needed health as well as non-health data to help understand how the virus was spreading in real time and its impacts.

Source: Geoff Mulgan, Oliver Marsh, and Anina Henggeler, “Navigating the Crisis: How Governments Used Intelligence for Decision Making During the COVID-19 Pandemic”, International Public Policy Observatory, December 2022, p. 6.

Functional divisions make it hard for governments to think and act holistically, or to look in a rounded way at the costs and benefits of alternative actions.

They needed models—for example, to judge if their hospitals were at risk of being overrun. They needed evidence—for example, on whether enforcing mask-wearing would be effective. And they needed to tap into the knowledge of citizens and frontline staff quickly to spot potential problems and frictions.

Most governments had to improvise new methods of organising that intelligence, particularly as they grappled not just with the pandemic’s immediate health challenges, but also with the knock-on challenges to economies, communities, mental health, school systems and sectors such as hospitality. The innovations included mass serological testing (which showed, for example in India, that most schoolchildren had already had the virus even as schools were being shut down). They included analysis of sewage, now being done in several thousand locations, as well as mobilising mobile phone and credit card data to target lockdowns or using citizen generated data on symptoms to track new variants. There was an equally impressive explosion of research and evidence; and innovative approaches to problem solving and creativity, from vaccine development to Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

But the stress of the crisis also showed up many deficiencies which often contributed to misplaced actions. The most basic was that almost every government divided the intelligence task both by function, with separate teams responsible for data, statistics, science advice, economics, and by departmental silos of health, finance, education and so on. This may have been necessary in the 20th century but given the availability of new technological tools, this approach was no longer fit for purpose. On the contrary, these functional divisions made it hard for governments to think and act holistically—to weigh up physical health risks against mental health ones, or to look in a rounded way at the costs and benefits of alternative actions. They made it even harder for governments to think synthetically. This lack of effective methods for intelligence led to many inefficiencies.

In our study, we suggested that future governments should organise intelligence in much more systematic and integrated ways, with teams charged with looking at intelligence in the round, focused on the outcomes they are trying to achieve, and then drawing on a range of sources to provide this. Such methods will be relevant to everything from Net Zero to tackling difficult issues such as rises in economic inactivity or population mental health. Net Zero is a particularly live example, with a huge upsurge of initiatives to gather research, evidence and data, but still major challenges in making that knowledge used and useful.2

Only with transformed structures, processes and cultures will it be possible to see more clearly what is working and what isn’t, to generate solutions faster and to direct resources to where they are needed most urgently.

Money: Reforming Public Finance

There are also implications for how money is organised. Governments are meant to be there for the long term: able to defend their people, guarantee their pensions or cope with big challenges like climate change. Yet they are often trapped by the tyranny of immediate pressures. This is particularly true in relation to finance, which has seen surprisingly few innovations in recent years to better align how government works with what it needs to do.

It is vital to know not just which areas of spending will achieve the most, but also which cuts could backfire.

Money is the fuel for much of the daily life of governments, which are often engaged in endless battles over budget allocations and priorities. But the ways in which finance is organised are at odds with what’s needed in three vitally important ways.

First, there is a common failure of time horizons and investment. Spending on physical assets and investments in infrastructures are appraised using rigorous investment methods: i.e., by analysing the link between present day costs and long-term returns from buildings, roads, airports, etc. By contrast, most spending on people—which includes most public spending on health, education and social security—is organised on an annual basis, and without any attempts to look at long-term impacts or returns.

Yet people now often last longer than infrastructures. For example, for children born in 2020, the average life expectancy in OECD countries is over 80. There have been many attempts to gather more systematic evidence on the returns to preventive spending, or the multiplier effects of investment in early years or for that matter research and development. But none of these are integrated into budget setting procedures.

Source: Geoff Mulgan, Silva Mertsola, Mikael Sokero, et al., “Anticipatory Public Budgeting: Adapting Public Finance for the Challenges of the 21st Century”, UAE Global Innovation Council, 2021, p. 22.

The related problem is the lack of effective ways to link inputs and outputs and outcomes, so that governments can be clear how different spending choices will achieve results over time. Again, there have been many attempts to evaluate the impacts of different programmes and interventions. But no government uses data systematically to tag the intended objectives of spending, of the beneficiary geography or population groups, in ways that would then make it possible to learn systematically, or to train machine learning tools in future.

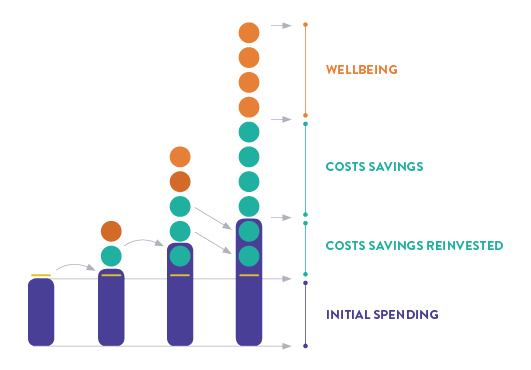

There have been many promising experiments over the years to address these problems, though all remain marginal. They include the shift to accrual-based accounting in many governments and introducing ‘phenomenon-based’ budgeting for complex and cross-sectoral phenomena (e.g., gender, SDGs or children) which don’t fit neatly into existing government structures. They also include the analysis of multipliers: looking at how some kinds of spending achieve cross-cutting impacts or save money (such as the UK’s ‘Public Pound Multiplier’ which draws, for example, on evidence that preventative action on smoking can deliver a £1.7-billion savings in return for a £300-million investment). This is a crucial concept for the future of public finance, particularly in times of shortage. It is vital to know not just which areas of spending will achieve the most, but also which cuts could backfire. Boomerang cuts are familiar to anyone who has worked in public services: the equivalent of cutting maintenance for roofs which then leads to much higher costs later when the roof falls in.

It is much harder to work out how to save money without doing harm.

There are also useful lessons to be learned from the world of impact investment which has become more rigorous in measuring social and financial returns, at least for individual projects and programmes. Part of the value of ideas like social impact bonds, which I helped develop in the 2000s, is to clarify the link between inputs of money and outcomes achieved.

Many countries have sophisticated machineries for public finance. In the USA, various bodies—including the Office of Budget Management, the Congressional Budget Office and the General Accounting Office—prepare long-term budget projections (75 years out in the case of the Social Security Administration) to aid decision making. The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility comments publicly on the long-term effects of budget decisions—though only taking account of first order effects (i.e., the overall fiscal position rather than the value created by spending in fields like health and education). The OECD has at various times in the past looked at long-term budget planning issues. These all attempt to look at stocks and balance sheets as well as flows.

But all these focus primarily on fiscal balance sheets. Few analyse rates of return on the assets they hold (or organise national registers of assets). Even less use is made of intangible measures in the public sector, though these are now routinely measured in the private sector, or balance sheets taking account of human or natural capital.

As a result, these fall far short of what’s needed, which is a 20-year programme to realign public finance with the priorities of the period. That will involve mapping all spending in terms of likely impacts over time and tagging spending data with data on purposes. It will rarely be possible to turn these into a return on investment (ROI) figure, but greater clarity on what is intended to be achieved, for example, for R&D or education, and then learning from results, is vital for governments to be effective in the decades ahead.3

This will be even more vital as hard choices have to be made about what to protect, what to cut and what to expand. Without some sense of likely impacts over time, governments will make even more arbitrary decisions and will be even more at risk of boomerang effects of the kind that the UK has suffered, with strong evidence now that cuts in the early 2010s have had disastrous effects later in the decade on everything, from life expectancy to productivity.

Economies and Economising

It is not hard to come up with good suggestions for spending more money. It is much harder to work out how to save money without doing harm. Much of the world is always looking for ways to be frugal, and even the rich countries are now going through another period of stringency. Such periods of retrenchment can be bad for innovation and creativity. But there are ways to combine imagination and reductions in spending.

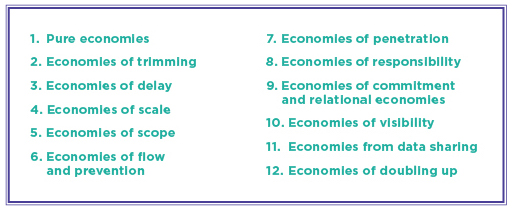

Here, I share methods developed to help public officials having to make significant cuts during the period of austerity. In some respects, they are very simple. They list a series of ways in which services can save money, providing a prompt for creative thinking about how to cope with cuts. But the aim is also to prompt deeper questions, about how to organise public services, and about the relationship between the state and citizens.

Most economists are familiar with economies of scale and scope, but much less familiar with notions of relational economies, or economies of flow, or economies of penetration, which should be part of their armoury. The framework also points to more lateral ways of saving money—for example, asking where new kinds of public commitment can be mobilised, or where transparency can reduce costs.

To make this practical, I like working with small groups of frontline staff or managers to generate options under each of the twelve headings (see Table below), and then to assess which ones were viable in the short, medium or long term. Most groups can quickly generate options for achieving 10%, 20% or 50% savings, including very radical ones.

Sometimes it is best to start off by helping people to become familiar with the approach by taking a live example—such as rural bus services, libraries or nursery education—and showing the options under each heading. Then some shared grounding in current data (e.g., costs, unit costs, etc.) can be brought in to help sharpen the discussion, and lead to more specific proposals.

Public services notoriously suffer from what’s sometimes called ‘Baumol’s disease’. Because productivity is hard to increase in fields like classroom teaching or running a theatre, the relative costs of public services tend to increase over time. Methods such as this are at least a partial and healthier alternative to the assumption that hard times must always bring about damaging cuts.

These various approaches all connect with each other—they are all about using intelligence, money and relationships in creative ways to rethink how government can work more effectively. Crises can be productive moments for achieving shifts—and one definition of good leadership is the ability to use the smallest crisis for the greatest impact. The alternative is retreat and stagnation.

Prompts for Economising Public Services

The approach starts off by looking at the traditional tools, which are the first options considered when a department must save money.

Traditional Tools

- Pure economies

Stopping doing things (e.g., fewer bin collections, closing rail lines and bus services, closing libraries) - Economies of trimming

Freezes, efficiency savings (e.g., 5% cuts to pay or opening times), shorter school days - Economies of delay

To capital, pay rises, procurement, maintenance, improvements

We then move onto less familiar ground, using a more creative economic lens to think about how a service could be reorganised. Much of the digital economy has grown by applying similar ideas to everything from shopping to dating.

Economic Restructuring

- Economies of scale

E.g., Aggregating call centres or back-office functions. These have been exaggerated in the past (small governments and municipalities are often just as efficient as big ones) but they can sometimes deliver big savings. - Economies of scope

E.g., Combining multiple functions in one-stop shops, multipurpose personal advisers, neighbourhood media, extending roles, standardised identification or payments. Much recent digital innovation has essentially helped with this—such as Estonia’s X-road platform or India’s Aadhaar. - Economies of flow and prevention

E.g., Hospitals specialising in a few operations and so improving efficiency, cutting bottlenecks or easing transitions, for example out of prison or from school into work. A related concept is reducing failure demand (such as recidivism or hospitals with repeated re-admissions), helped by tools like outcome-based funding or investing in preventive health. Many of the greatest costs in public systems accumulate around blocked flows of this kind. - Economies of penetration

These are economies that result from concentrating a service or cluster of services in a locality. In energy, this can be done by Combined Heat and Power schemes, and in housing, often through roles such as street concierges.

Next come options that involve a renegotiation of the implicit contracts between states and citizens.

Revised Social Contracts

- Economies of responsibility involve passing responsibility out to citizens

E.g. For COVID self-testing, separating out waste, or self-packing as supermarkets shifted the role of packing from paid staff to customers. - Economies of commitment and relational economies

These are economies that flow from shifting tasks to more committed providers, or ones with a sense of relationship. This can apply to professional social work and care, but also to making the most of the community, for example using volunteer bus drivers for marginal rural bus services or organising neighbours to watch out for people with dementia.

Next come some ways of using digital to cut unnecessary costs.

Smart Tools

- Economies of visibility come from mobilising public eyes and the power of shame

E.g., Making parliamentarian’s expenses more public and reducing them; the same principle applies to public contracts of all kinds. - Economies from data sharing

Open data enabling innovation, competition and new models (as has happened in finance, energy and transport, where much has been learned about the value of open data—for example, opening public transport data to enable new apps, or opening up banking data to third parties to prompt innovation).

Joined-Up Thinking

- Economies of doubling up

Finally, there are often options for joining up the work of government in creative ways, promoting actions that address two problems or needs simultaneously (such as training up the young unemployed to work on home retrofit programmes).

It should be apparent that these prompts can help us rethink public services not as static things that have to always take the same forms, but rather as building blocks that can often be organised in different ways.

NOTES

- Geoff Mulgan, Oliver Marsh, and Anina Henggeler, “Navigating the Crisis: How Governments Used Intelligence for Decision Making During the COVID-19 Pandemic”, International Public Policy Observatory, December 2022, accessed February 15, 2023, theippo.co.uk/how-governments-used-intelligence-decision-making-covid19-pandemic

- Geoff Mulgan, “Net Zero: Mobilising Knowledge for Easier, Effective Decision Making”, International Public Policy Observatory, January 9, 2023, accessed February 15, 2023, https://theippo.co.uk/net-zero-mobilising-knowledge-easier-effective-decision-making/.

- Geoff Mulgan, Silva Mertsola, Mikael Sokero et al., “Anticipatory Public Budgeting: Adapting Public Finance for the Challenges of the 21st Century”, UAE Global Innovation Council, 2021, accessed February 15, 2023, https://gic.mbrcgi.gov.ae/storage/post/f6bTTIppsLhLElDnEVTTTRm36I3t70HP4rY722t0.pdf.