Budget 4.0: Optimising for Better Outcomes

ETHOS Issue 25, April 2023

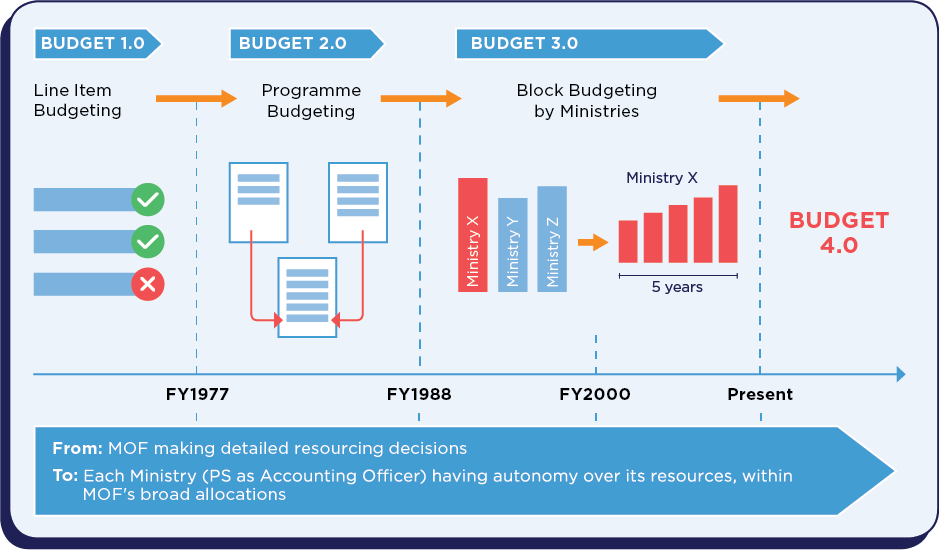

The Singapore Government’s budgeting framework continually evolves to meet the needs of our people and the challenges of our national context. We have matured, from a traditional bottom-up system based on detailed line items (Budget 1.0) and programme budgets (Budget 2.0), to a system which emphasises robust aggregate limits on spending while providing line ministries with maximum discretion to make final allocations among their various programmes (Budget 3.0). While Budget 3.0 is still relevant and important for our fiscal management, significant changes in our operating environment have prompted further improvements to our budgeting framework.

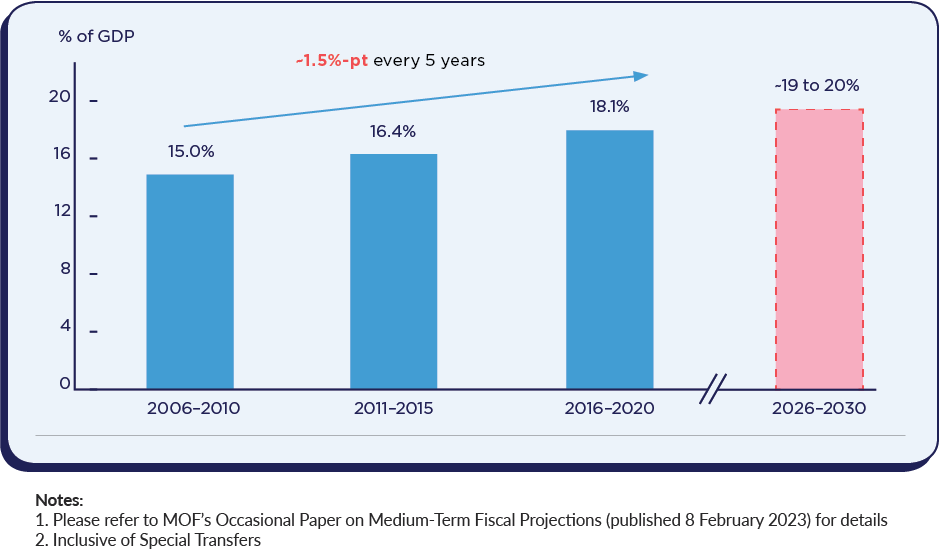

Expenditure on government policies has been increasing significantly with time: from 15.0% of GDP in FY2006–2010 to 18.1% of GDP in FY2016–2020. This has been funded sustainably through increasing taxes and a Net Investment Returns spending framework that strikes a fair balance between the interests of today and tomorrow. However, we anticipate pressures for public expenditure to continue rising. Geopolitical uncertainty and lessons learnt from the COVID pandemic will increase the size of government and expenditure on resilience. Our ageing population and slowing resident labour force growth will limit the amount of revenues we collect, while requiring greater expenditure on healthcare and social security. In the longer term, economic growth is expected to plateau, further limiting revenue growth.

Meanwhile, problems faced by the Government have been growing in complexity and scope: these will require multi-agency collaboration, such as for digitalisation, social service delivery, and workforce and skills development. Without an agreed method for providing resources for managing cross-cutting issues amongst the various agencies working on them, policy development and implementation may be impeded. Thus, there is a need for greater upstream intervention to allow cross-agency budgeting for agencies to achieve their collective goals.

There have also been greater demands on the public sector to respond more quickly to non-routine, uncertain and emergent problems that run counter to the regular cycle of traditional budgeting. We have had to mount prompt policy responses to abrupt and unforeseen challenges such as the COVID pandemic and heightened inflation due to supply chain disruptions induced by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Many of these policy responses have been unprecedented and innovative, made possible only because of the Government’s ability to allocate resources nimbly and decisively.1

There have been greater demands on the public sector to respond more quickly to non-routine, uncertain and emergent problems.

To be better prepared for such challenges, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) is implementing three improvements to Budget 3.0. Collectively, these make up Budget 4.0.

Strengthening Reallocation

The first prong of Budget 4.0 involves strengthening reallocation mechanisms, to allow the shifting of funds from less relevant programmes to emerging and meritorious areas of need. If all our resources were allocated to individual Ministries as block budgets, there would be no room for any reallocation. To reallocate effectively, we need to increase the size of our reallocative resource pools and reduce the size of resource buffers decentralised within individual block budgets and statutory boards. For Ministries, this means a baseline that grows more slowly, resulting in pressures to better manage programme costs and to review the continued relevance of programmes. Statutory boards would retain smaller amounts of monies for near-term operational needs, instead of accumulating large surpluses for asset replacement and acquisition of new assets over the longer term.

On the manpower front, the Public Service is making broad moves to right-size Ministries’ permanent headcount baselines, to reallocate scarce public sector manpower resources towards new and emerging needs.

As our resident labour force growth slows to near zero after the end of the decade, we have to be highly discerning about where we deploy our officers, or there will be fewer residents available for the workforce. We have no choice, unless the public were to accept more foreign workers within our shores, which would introduce new stresses to our social fabric.

Fostering Alignment

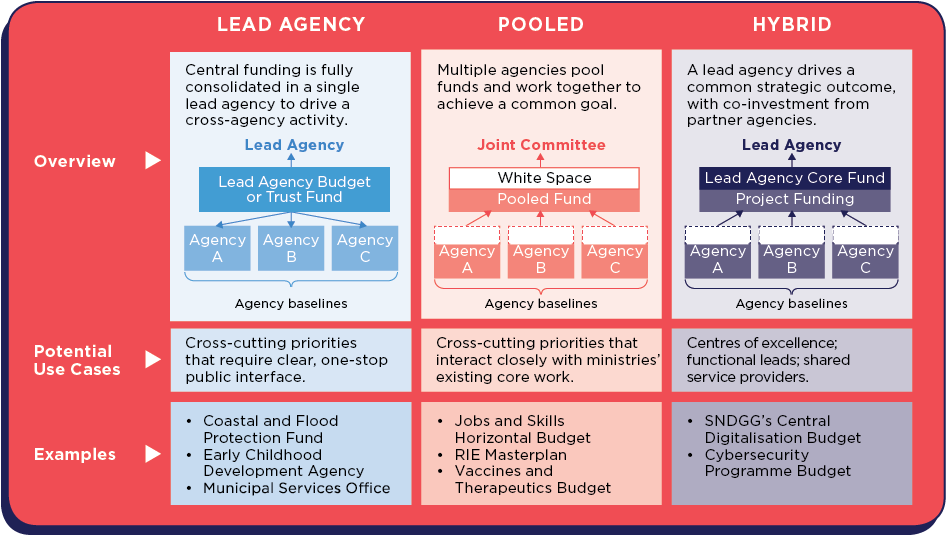

Creating joint budgets to foster greater cross-agency collaboration on specific issues is MOF’s way of intervening for greater Whole-of-Government (WOG) and multi-agency outcomes. Through the joint budgets, agencies are expected to rationalise efforts, achieve greater cost effectiveness and enhance accountability for shared outcomes. Operationally, MOF will partner parties interested in starting a joint budget to ensure appropriate governance structures, apportionment of resources and responsibilities, as well as proper tracking of KPIs and utilisation.

There are broadly three models of joint budgeting arrangements (see Figure 3), each suited for different purposes.

Enhancing Nimbleness

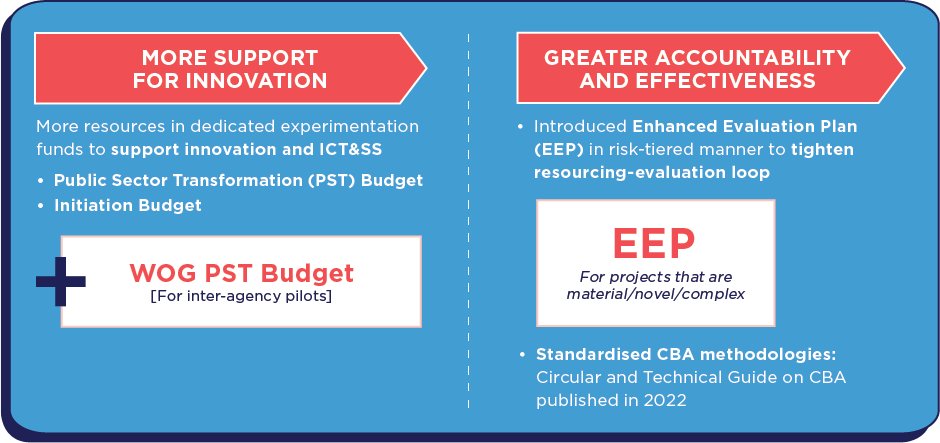

To better prepare for quicker responses to non-routine, uncertain and emergent problems, the pace of reallocation will be increased through faster evaluation and more efficient allocation of resources. Proposals will be prioritised based on the projects’ risk-scored strategic importance, urgency and innovative value. Efforts spent on evaluation will be commensurate with the resource requirements and risk level of each project. There will also be greater leeway for MOF to time-shift reallocative resource pools across financial years to better resource agencies’ needs. This will help cater for unexpected and/or lumpy expenditure requested of our reallocative pools.

For agencies seeking to validate pilot projects at the agency level, resources are available via the Public Service Transformation and Initiation Budgets. The WOG Public Service Transformation budget is also available for cross-agency pilot projects. Such budgets are intended to foster a culture of experimentation and innovation for incipient projects in the Public Service, anticipating that successful pilots might be scaled up for greater benefit over the medium to long term.

Since providing speedier funding invariably means giving up some degree of accuracy, additional guardrails have been introduced to ensure greater accountability and effectiveness in the use of such funds. For instance, projects receiving additional funding will be periodically evaluated for viability and outcomes, particularly for large, novel or complex ones. Their resource utilisation will also be tracked in existing and future data platforms, which will allow for data analytics to aid better decision-making, such as for the sizing of future reallocation pools. To facilitate better comparability between projects, inputs for cost-benefit analyses will be standardised to enable better prioritisation of competing needs.

Conclusion

Every agency and public officer has a role to make Budget 4.0 effective, because our fiscal and manpower constraints are national, real, and binding. While we have traditionally thought of manpower shortages as the most binding constraint, recent experiences have reminded us that raising new taxes can be challenging too. New policies and programmes must be designed with these resource constraints in mind, so the trade-offs in outcomes between options of different resourcing needs can be fully considered. Agencies must keep an active and keen eye out for where functions are no longer relevant and can be deprioritised, and seek out productivity enhancements where possible.

Optimising the system at a macro-level will be of limited benefit if individual officers are not ready or able to maximise spending effectiveness and outcomes.

An important role of leadership will be to pay attention to change management and help their organisations and people to reskill and pivot as demands change. Leaders and managers should think about how to bring out the best in their staff, which will involve not just drawing out greater productivity, but keeping them motivated, engaged, and well equipped for their mission

While Budget 4.0 effects system-wide changes to our budgeting framework, freeing up fiscal space for emerging needs is the collective responsibility of every public officer. Innovation and transformation must be part of our DNA as public officers. Individual officers should constantly ask themselves whether they are doing enough to provide for the nation and for the future, which will entail making the most of available resources.

Optimising the system at a macro-level will be of limited benefit if individual officers are not ready or able to maximise spending effectiveness and outcomes. In the words of former Head of Civil Service and PS (Finance) Mr Lim Siong Guan, there is never enough money to fund all the things the public want from the Government. Therefore, it is important that we prioritise Singapore’s needs and create the conditions to resource these needs in a sustainable and principled manner.

NOTE

- Examples of such policy responses to address the pandemic include: the Jobs Support Scheme, the Care and Support Package, the COVID-19 Recovery Grant, the Jobs Growth Incentive, SGUnited Jobs and Skills, Rental Relief and Cash Grant and so on. Together, they helped Singapore avoid long-term scarring from COVID-19. For more information, please see "Assessment of the Impact of Key COVID-19 Budget Measures", published by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) on 17 February 2022.

FURTHER READING:

- Ministry of Finance, “Occasional Paper on Medium-Term Fiscal Projections”, February 8, 2023, accessed February 16, 2023, https://www.mof.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/news-and-publications/featured-reports/occasional-paper-(final).pdf .