The Agile Way of Working

ETHOS Issue 21, July 2019

Agile is an approach, commonly used in software development, which has been widely adopted by tech organisations to deliver their products to consumers more efficiently. The public sector, which has traditionally not used Agile ways of working, can benefit from adopting Agile in many areas, including strategy, policy, communications, HR, and IT. In our own teams, we use Agile as a methodology to enable our teams to keep work organised and productive whilst being able to adapt to change rapidly.

What Is Agile?

Originally based on the principles published in the Agile Manifesto,

1

the Agile approach encourages a culture of working based on the values of autonomy, collaboration, communication, iterative working, user-centricity and competence:

Agile emphasises decision-making that gives weight to the views of those with relevant professional expertise, rather than those most senior in the hierarchy.

Why Agile?

The main argument for pursuing an Agile approach is to achieve swifter decision-making on complex projects within a volatile and uncertain operating environment. Hierarchy-based organisations were designed for the industrial era—routine work, efficiencies through standardisation, and a compliant workforce. Agile organisations are designed for our post-industrial era—work that requires creative problem-solving, collaboration across functions, and a high degree of responsiveness to changing circumstances.

As managers, we find that Agile provides a sense of momentum for our teams and gives us a clearer picture of what everyone is doing. We save time otherwise spent “managing” so that we can “get work done”. As team members, we have found that the Agile way of working has kept us motivated and focused. For our teams, who grapple with uncertainty and unexpected challenges, the consistency of our Agile practices—daily habits—provides a sense of stability. In our experience, working in Agile teams reduces our stress levels and allows us to be more productive.

Agile is a way of working well-suited to highly skilled, self-motivated teams who value their autonomy; culturally, it fits the work styles of many millennials. Our personal experience working in Agile teams is that it feels like we work in progressive organisations. We feel respected as professionals: trusted to get our work done and to be accountable for it—the opposite of being micro-managed.

Indeed, organisations that practise Agile methodologies have been found to have a 70% chance of being in the top quartile for organisational health: the most reliable indicator of performance over the long run.3

Agile is well-suited to highly skilled, self-motivated teams who value their autonomy; culturally, it fits the work styles of many millennials.

How To Practice Agile

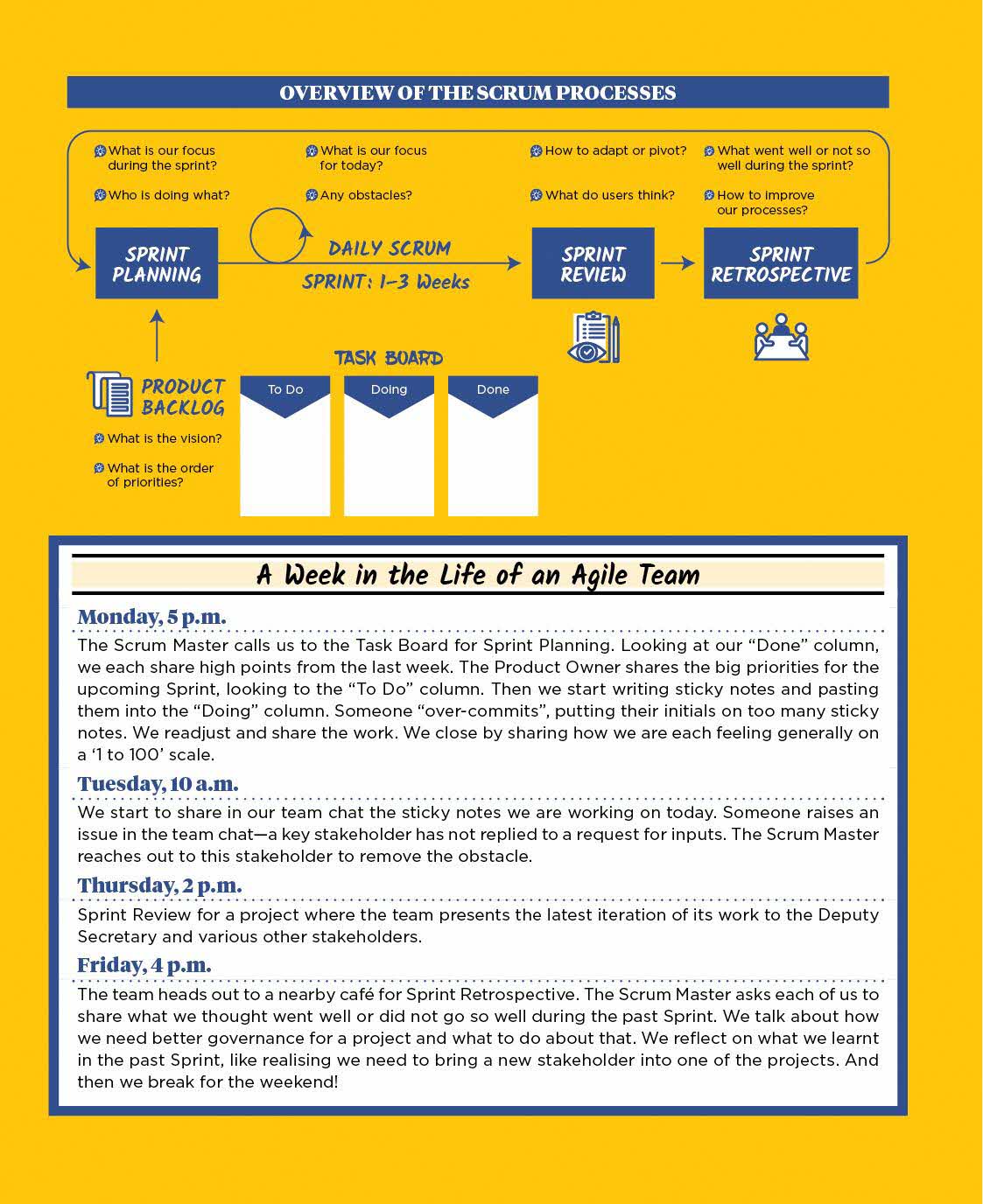

How might you apply Agile techniques in your own team or department? Each team will need to find its own tempo and adapt these processes to suit its unique context.

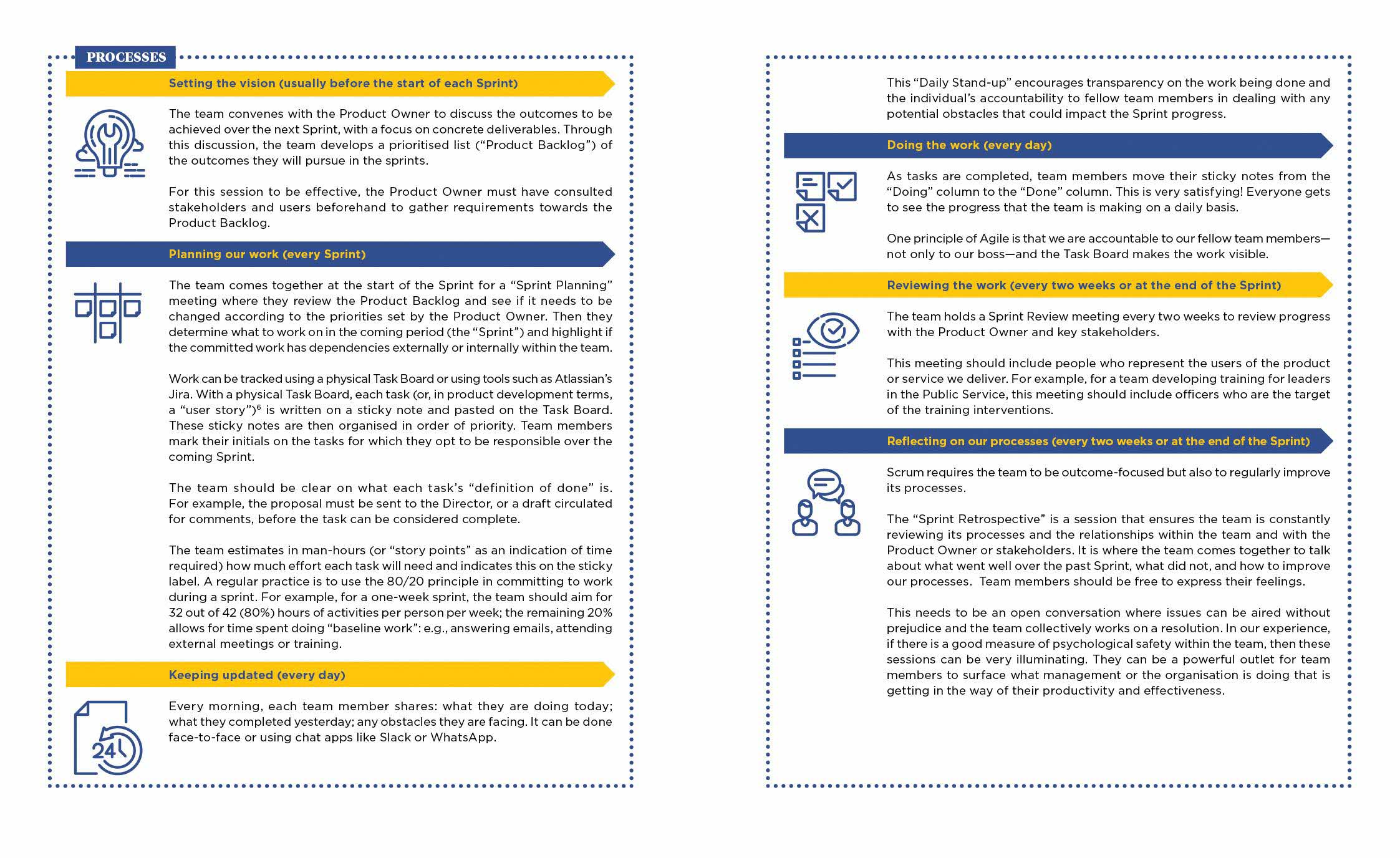

The team at the Public Service Division’s Digital Workplace Programme Office (DPWO) uses Scrum,4 which is the most widely-used Agile methodology. Scrum project teams have roles and “rituals”—i.e., the processes used to organise a team’s work. For these processes to be effective, the team must be relatively small (i.e., fewer than ten people). There must also be considerable inter-dependencies between the tasks that the various individuals in the team are doing.

Product Owner

This is typically the Director or department head who is accountable for the success of the programme. The Product Owner sets the vision for the project and signs off on the priorities the team needs to deliver. Accountable for meeting the required outcomes, the Product Owner also engages the project’s users and stakeholders and is responsible for translating the team’s output into value for the organisation. The Product Owner must be experienced enough to be able to get alignment from stakeholders and have the confidence to manage stakeholder demands so that the team can stay focused on the most high-value tasks.

Scrum Master

The resident problem-solver, the Scrum Master facilitates the relationship between the team and the Product Owner. This can be any member of the team: preferably a senior with relevant experience and Scrum Master certification.5 The person in this role facilitates the Scrum processes and ensures that meetings are adhered to and productive in achieving team outcomes. The Scrum Master is responsible for the productivity of the team and must remove any impediments to team progress: by improving inefficient organisational processes and ensuring the team has the resources they need, for instance. This includes protecting the team from external influences (e.g., unplanned work requests) to avoid impacting their velocity. The Scrum Master also provides guidance to less experienced team members in understanding Scrum and how it is being applied. The Scrum Master must have enough clout in the organisation to deal effectively with any obstacles the team may face.

Mindset Shifts for the Agile Organisation

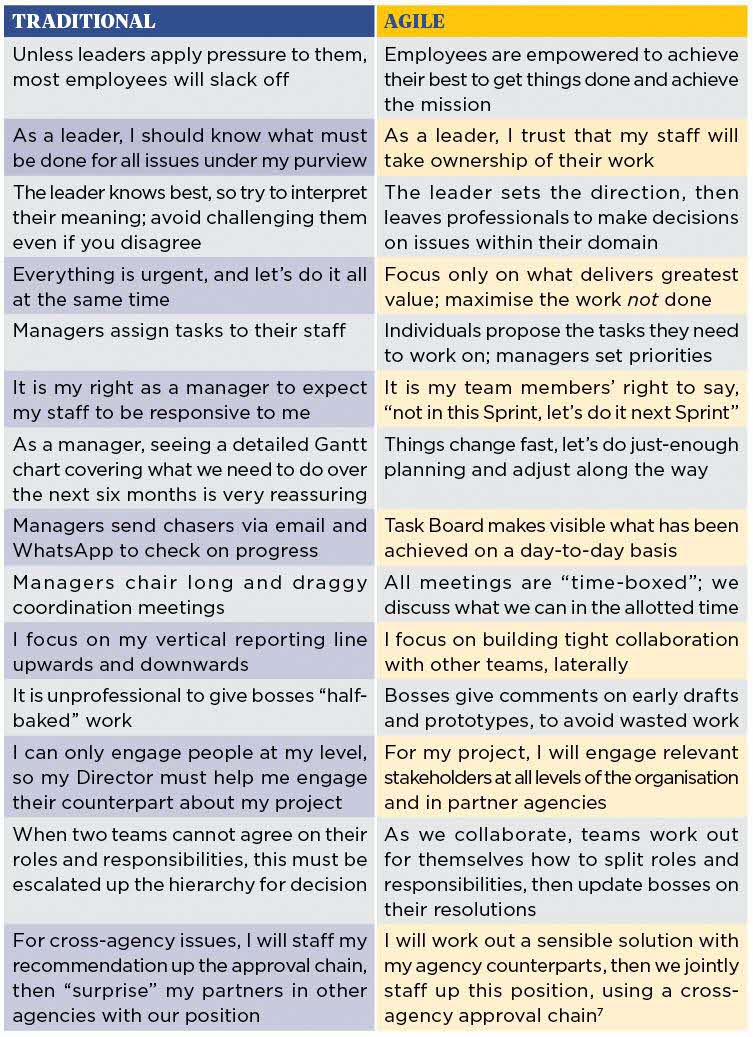

Agile is ultimately not about following a set of processes; it is about a mindset and daily habits of working. It takes a lot of conscious effort to switch from a traditional “bureaucratic” public sector work style towards a more Agile way of working.

Challenges and Limitations

Agile methodologies work best for complex, non-routine work in an environment of rapid change. They may not be suited where work processes are standardised and stable, proceeding sequentially in phases that are dependent on previous phases, and where the scope has been clearly defined before work begins and changes would be costly (such as “waterfall” projects, commonly seen in construction).

Agile methodologies work best for complex, non-routine work in an environment of rapid change.

The fluid nature of Agile approaches is typically more suited to work that requires creativity and where there is some appetite for failure. However, there is some evidence that Agile can work even where risk tolerance is low: Saab used Agile methodologies for developing fighter aircraft.8

One serious challenge for practitioners is how to make Agile work when the wider organisation is still run on traditional command-and-control principles. Stephen Denning observes of such situations in The Age of Agile: “Either the Agile teams will take over the organisation, or more likely, the bureaucracy will crush the Agile teams.9 This would be a pity—as Li Yiyang, a Manager in the Digital Workplace team of Singapore’s Public Service Division puts it: “Scrum organises work so much more efficiently, I hope I will never have to return to the old way of working.”

One serious challenge is how to make Agile work when the wider organisation is still run on traditional command-and-control principles.

Given Agile’s benefits, it is important that leaders in traditional public sector organisations learn how to manage Agile teams. Here, Low Xin Wei, Director of Strategy and Masterplanning at Singapore’s National Research Foundation, has some advice: “For a Director whose team is embarking on an Agile journey, there is a learning curve involved, but it is worthwhile to stay the course. For directing passionate young officers on dynamic and complex issues, this is a way of working that keeps them engaged and brings about a sense of ownership not possible with traditional management forms.”

NOTES

- Manifesto for Agile Software Development (website), accessed July 1, 2019, https://agilemanifesto.org/iso/en/manifesto.html.

- Wouter Aghina et al., “The Five Trademarks of Agile Organizations”, McKinsey Quarterly, December 2017.

- Michael Bazigos, Aaron De Smet and Chris Gagnon, “Why Agility Pays”, McKinsey Quarterly, December 2015.

- Jeff Sutherland, Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time (London: Random House, 2014).

- Certified ScrumMaster (CSM) certification courses are widely available in the market, for e.g., by ScrumAlliance.

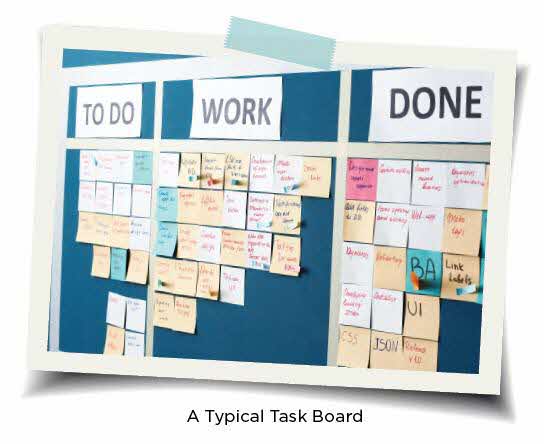

- Tasks are the smallest unit of work, and usually assigned to a single team member of the team to complete. In product development, “user stories” help the team group and track these tasks as an outcome driven by user requirements. So a feature (e.g., login on a webpage) may be one of the main deliverables of a user story in addition to areas like user-experience, security, compliance and so on.

- For example, for issues involving both PSD and SNDGO, the relevant PSD and SNDGO Directors are cleared jointly on one email chain, then the issue is staffed up to PS(PSD) and PS(SNDG) jointly.

- Darrell Rigby, Jeff Sutherland & Hirotaka Takeuchi, “Embracing Agile”, Harvard Business Review, May 2016.

- Stephen Denning, The Age of Agile: How Smart Companies Are Transforming the Way Work Gets Done (New York: American Management Association, 2018).