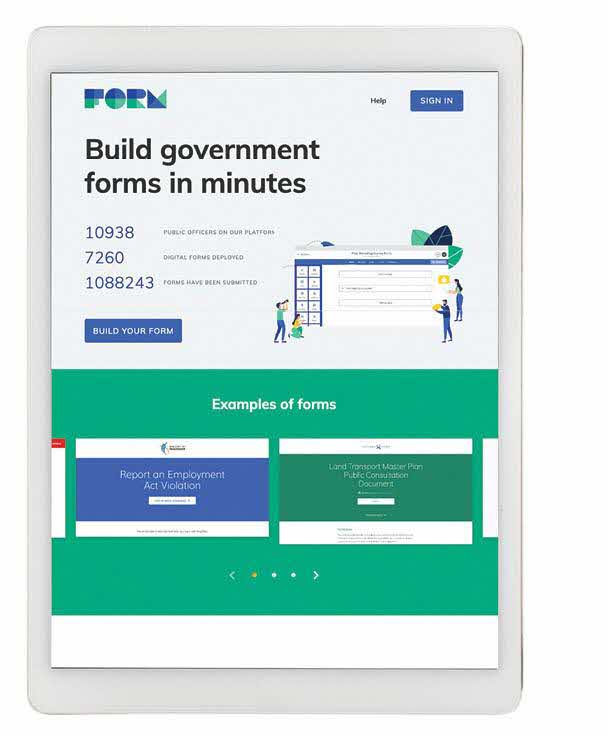

FormSG: From Idea to Hit Platform in a Year

ETHOS Issue 21, July 2019

FormSG began in August 2017 as an idea discussed by a few of us at GovTech, for which we were trying to find potential users. One of our earliest users was the Municipal Services Office (MSO), for which we were digitising a pigeon inspection form. MSO staff were complaining that they were spending tens of hours doing manual data entry. I thought it would be a weekend side project to solve this problem. What my team and I ended up with, one-and-a-half years later, was something that tens of thousands of officers now use to digitise thousands of forms filled in by millions of Singaporeans. And despite not having a policy mandating its use, our platform is now used by just about every single government agency in Singapore.

How did we get this far this quickly? I believe it was a combination of luck, hard work, and the deliberate approach we took to development. Here’s how we did it:

1. Understand the Scale of the Problem

We realised we were solving an Everest-scale problem. Ask yourself—how many paper forms do you fill in a year? If the average Singaporean fills in six a year, this means over 30 million paper submissions each year! All this data then has to be manually entered or digitised, which calls for an army of data entry staff. Paper submissions are usually also stored for some time. If you do the math, all this paper stacks up to a mountain almost the size of Everest. And this happens every year.

2. Start by Really Solving One Person’s Problem

We didn’t start by building a rocket to scale Everest. But neither did we make a “minimal viable product” (MVP) either. No one is going to remember or bother using an MVP that barely satisfies them. The first product we build should be a complete product that precisely solves one person’s problem. Our Version 1 wasn’t a form builder tool with two fields. It was a full-fledged form with all the fields that MSO needed. I was manually coding each and every field. Once we solved MSO’s problem, they started sharing our good work with their peers from other agencies, which earned us some traction. When our supply of forms couldn’t keep pace with demand, we decided to build a form builder.

3. Listen to Users’ Problems, Not their Solutions

We listened to users for their problems, but not their solutions. In the late 1800s, a rider on a slow horse would have asked for a faster horse, not a car. Sometimes a user doesn’t know what they need until you put a solution in front of them. Our initial users, such as MSO, asked us to build something like Google Forms, but for sensitive data. A sensible solution might have been to code something like Google Forms, then host it on government data centres. But computing cores on self-hosted data centres could cost S$5,000 per month or more, compared to S$50 per month from commercial cloud services. So instead we hosted the platform on the cloud, but did not store the data there. Each time someone submits a form, data is emailed directly to a public officer’s secure Government email. Users loved that there were no concerns over data governance, privacy or security with our product. A meeting with the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) was shortened from 1.5 hours to 15 mins, after I told them: “We don’t store your data”!

No one is going to remember or bother using a minimal viable product that barely satisfies them.

4. Focus on Getting the Work Done, Not How It Is Done

We did not spend much time on processes. When a user asked how we were able to ship useful features so rapidly with just a team of three, I told him we focused on two things: talking to users and writing code. The Agile method to running software development might make sense for larger teams, but for a small team like ours it adds too much overhead. If we did sprint planning, story pointing and retrospectives, we would have 40% less time to write code. Hence as the product manager, it was just me writing the stories, estimating development effort needed and then assigning them. If we find a process that takes up 20% of our time but increases productivity by only 10%, then it makes sense to remove that process. For example, we started with daily stand-ups—meet-ups of 15 minutes or less where the team literally stands—but ditched it because it made more sense to talk to each other only when there was a need to.

5. Make Sure It’s Good, then Let Success Market Itself

We focused on growth only after we were sure we had a good product. First, a good product is going to sell itself. Elon Musk has highlighted never having spent a single dollar on marketing for his Tesla cars. Steve Jobs advocated the importance of product people and not sales people running tech companies. The biggest reason FormSG grew to serve the entire government was because we built a product that people loved. And people share products they love with those around them. Second, if we focused on marketing our product or pushing for a mandate too early, we might end up shoving a bad product down the throats of our users. That’s a quick way to destroy user trust. Because our users loved FormSG, it was easier to introduce other products we’ve built, such as by.gov.sg, a government link shortener.

6. Kill Your Darlings

We were very willing to dismantle old features. No one likes to undo their work. Or admit that their feature or product has failed. Which is why it’s not hard to find examples of failing products that still get resourced. Once we realise a feature or even an entire model is not working well, we remove them. In the early days, we had progress trackers to give users a sense of how far they were into the form. But on user testing we realised users weren’t gauging progress from the “23 of 40 questions answered” label, but the position of the scroll bar! Their eyes never once looked at our label, and continually moved back and forth from the scroll bar to the questions. So we removed progress tracking. And there were many other examples of us undoing things we had done.

Even today with thousands of officers already using our product, we are thinking of revamping our email model. Users dislike the email model because they have to man age email space, and have to manually run a script to collate emails into Excel. We are thinking of a way to store data so submissions can be downloaded directly from our website. But what about not wanting to store data on the cloud? We are now thinking of doing end-to-end encryption, similar to how WhatsApp stores its messages in its servers but does not actually have access to the content of those messages. The idea is that when you create a form, you’ll receive a password that is not seen by our server. When a user submits your form, the data is encrypted before being sent to our server. And when you want to view responses, that encrypted data is downloaded but you must provide the password to decrypt them. Even if our database were to be compromised, only the encrypted version of the data will be leaked, with no way to decrypt them unless the attacker has the passwords as well.

We built a product that people loved; and people share products they love with those around them.

7. Take the Initiative, Don’t Wait for the Stars To Align

We did not wait for others, but acted immediately to solve user problems. When we first started FormSG, some policy folks said that if Google Forms could handle classified data then that could be used to digitise government forms. But we built FormSG anyway because we didn’t want to wait for that to happen. We were also not confident that Google Forms, a tool best meant for quick and dirty surveys, could have all the features public officers need for official government applications.

There were also plans for a digital signature module. But instead of waiting for that module, we pushed for digitisation of forms with signatures. The Electronic Transactions Act does not prescribe a specific format for an electronic signature. Hence, something as simple as a SingPass login or a checksum-validated NRIC field could suffice as an electronic signature. These digital measures are likely harder to tamper than a wet ink signature. There were also plans for the Government Commercial Cloud to provide Intranet access to our Cloud hosted apps. Instead of waiting for that, we pushed for digitisation of Intranet forms. Although our form is on the Internet, a QR code of the form link can be emailed to officers for them to fill forms from their phones.

We consistently had a bias for action and made the most of the resources we had at hand. We never once delayed work just because we were waiting for someone else to build something.

Looking back, we never once took FormSG offline and said we needed to have a “build phase”. We launched from Week 2, and it has stayed online ever since.