Digital Government, Smart Nation: Pursuing Singapore’s Tech Imperative

ETHOS Issue 21, July 2019

What Is Smart Nation?

Through the Smart Nation initiative, we aim to make Singapore “an outstanding city in the world…for people to live, work and play in, where the human spirit flourishes.”1 To achieve this, we have to apply technology systematically and extensively, rather than in a piecemeal manner, to improve the lives of our people.

But first, why does Singapore need to be a Smart Nation? Growth in two main factors of production drove Singapore’s growth in the first 50 years: our labour force, and capital investment. As our population ages and the inflow of immigrants slows (given our finite physical space), labour as a factor of production will grow more slowly. Consumption as a percentage of GDP will also likely rise relative to investment as Singapore’s population ages. The main contribution to growth and prosperity will have to be total factor productivity, which could be achieved through a mix of technology and better business processes.

Besides continuing to build prosperous and flourishing lives for Singaporeans, Smart Nation can be a reason why home-grown talent would want to continue living here, and why foreign talent would want to relocate here. This is the magnetic pull exuded by the world’s leading cities, such as New York, London, San Francisco, Shanghai and Tokyo.

Smart Nation is also necessary to accelerate the process of integrating technology into our collective efforts to improve lives, lest Singapore fall behind relative to other global cities. Modern-day classrooms, hospitals and workplaces; the very concepts of retirement and a pension; the city in its horizontal spread (trains and cars) and vertical reach (elevators)—these improvements to human wellbeing were enabled by the first and second Industrial Revolutions. The nature of all these will shift again as the technologies of the fourth Industrial Revolution change our lives. The first two Industrial Revolutions allowed us to automate menial, physical chores. The third and fourth Industrial Revolutions are allowing us to automate even more of such tasks, and to devote a greater proportion of our lives to meaningful, enriching activities. To give a personal example: it used to be that vacations could be a stressful experience, because of the unfamiliarity with a new environment. These days, with Google Maps and review sites, travelling has become much less anxious and a lot more enjoyable.

Smart Nation: What It Takes

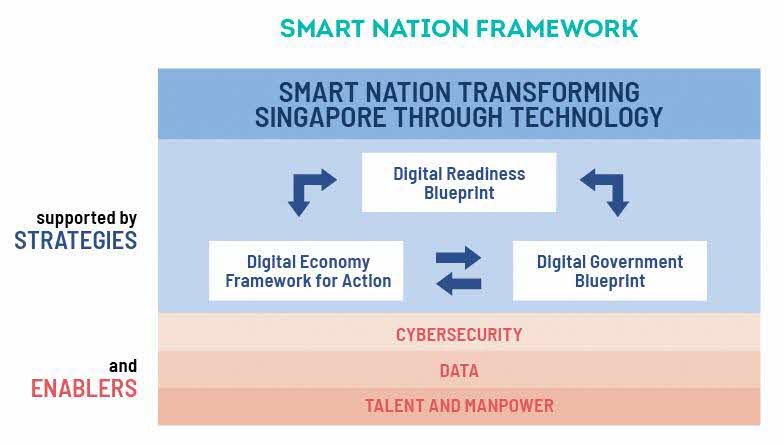

Building a Smart Nation is a whole-of-nation effort which can be thought of in terms of three pillars: Digital Government, Digital Economy, and Digital Society. The first pillar, led by the Smart Nation and Digital Government Group (SNDGG), involves agencies across the Public Service. The Ministry of Communications and Information (MCI) leads work for the other two pillars. Other articles in this issue discuss Digital Economy and Digital Society, so this article will focus on Digital Government.

Unlike in many other countries where innovation and the application of technology are driven by the private sector, in Singapore, the Government has traditionally set the pace. We expect digitalising the Government will set in motion deep changes that will spread to the private and people sectors.

Digital Government: Where Are We Today?

When it comes to Digital Government, Singapore is fortunate to be building on strong previous efforts. Our digitalisation journey started about three decades back, with the National Computerisation Programme in the 1980s. Led by the National Computer Board (now the Government Technology Agency or GovTech), the Programme focused on automating data, processes and systems. By the 2000s, we had shifted to providing government services online, first as websites and then as phone applications when mobile phones exploded in popularity. Since the 2010s, we have been focusing on making our services more integrated, and experimenting with different approaches to being citizen-centric.

Heading into the future, we are off to a good start. Most transactions between citizens and the Government today can be done online, and integrated apps that reduce the time taken to fulfil inter-agency requests have been growing in number. But such efforts have been sporadic or agency-led. A central, coordinating entity can accelerate the process, which was why SNDGG was formed in May 2017. Soon after our formation, we launched five Strategic National Projects: National Digital Identity, E-payments, Moments of Life, Smart Nation Sensor Platform and Smart Urban Mobility. Most of these are digital platforms, upon which more use cases can be explored over time.

In the course of the next two years, we have gone further than just having more projects and systems. We have also put in place policies and strategies, processes and organisational structures; we have also recruited and groomed talent to systematically exploit digital technologies and to sustain the momentum in the longer term. Collectively, these efforts will drive the Government to become digital to the core.

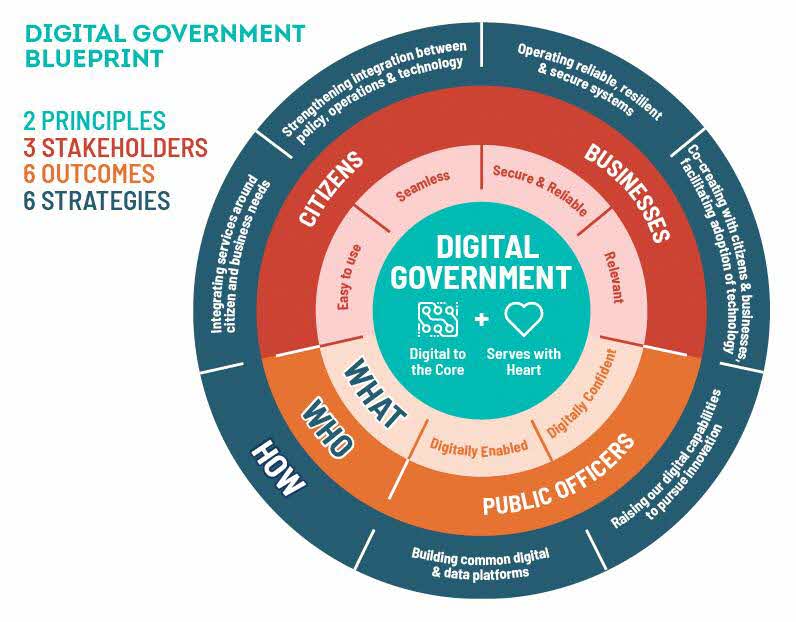

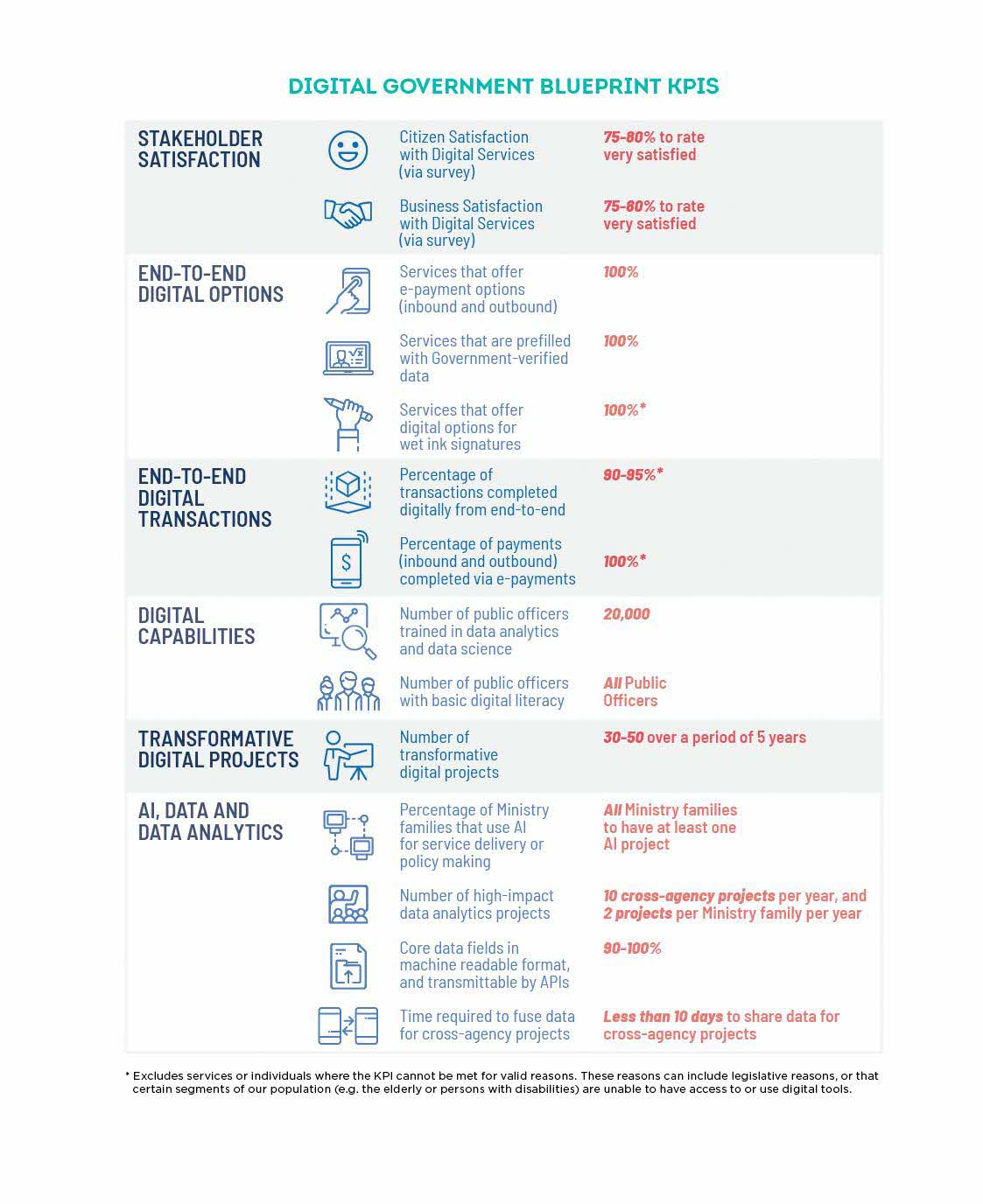

In the past, other than in agencies that have a heavy engineering component, technology did not feature often as an agenda item in policy forums and senior management meetings in the Government. This is shifting. Policymakers are increasingly taking responsibility for technology. For instance, all public agencies now have a role to play in achieving targets set out in the Digital Government Blueprint (DGB). Two such targets aim to achieve 75% to 80% citizen and business satisfaction levels with government digital services. We have made some progress in achieving these goals. Between 2017 and 2018, the score for citizen satisfaction rose from 73% to 78%, while the score for business satisfaction rose from 64% to 69%.

The DGB targets are ambitious but not unrealistic. For this reason, the DGB is a living document, so targets may be revised as we plan further digitalisation initiatives. For example, we will be updating the DGB when the National AI Strategy is ready later this year.

SNDGG has also been working with all Ministries to develop comprehensive plans for digitalisation. The first round of plans, completed in June 2018, was useful in quickly identifying “no-regrets” digital

initiatives that Ministries felt would be high in impact. Some of the initiatives, such as the Ministry of Home Affairs’ digitisation of death registration and the Ministry of the Environment and Water

Resources’ automated meter reading infrastructure that enables near real-time information on water consumption patterns, will significantly improve service delivery and how agencies operate.

However, the first round of plans was ultimately a list of projects. From 2020, Ministries will include digitalisation planning in their strategic planning cycle, so the plans are linked to and support the Ministries’ missions. Integrating with the strategic planning cycle also means resourcing, data requirements and capability development will be simultaneously considered.

In addition, Ministries will be encouraged to explore digital technologies beyond application development, such as artificial intelligence (which allows more personalised and anticipatory

services), data analytics (which allows more evidence-based and data-driven policy making), and Internet of Things (IoT) or smart systems (which will go much further in creating a good living environment in Singapore). An agency that has made good progress on this front is the Ministry of Manpower, which has deployed cameras and sensors to improve the monitoring and enforcement of workplace safety at construction sites.

Policies and strategies, however well laid, can only have a chance of success if processes and structures are designed to facilitate the harnessing of technology.

For example, we are witnessing a paradigm shift where agencies are beginning to see technology not just as an expense, but also as an investment in new strategic capability: that it is about how technology can help agencies reach topline growth (faster time-to-market for services, improved service delivery) in achieving mission objectives. This is not to say that we are not striving to be cost-efficient in using technology, but that cost-efficiency should not be the only consideration.

But even if agencies are to treat technology as a strategic capability, conventional approaches to resourcing do not allow projects to be started quickly. The traditional funding cycle takes place only once a year, and if the project proposal is supported, there is still the calling for and then evaluation and awarding of tenders. For in-sourced projects, time is needed to hire developers. To put this in perspective: it can often take longer to obtain the resources for a project than to build a prototype. In addition, the project team has to work out pricing and commit to recovering system costs, before they have even had the chance to work out requirements with users.

We are witnessing a paradigm shift where agencies are starting to see technology as a strategic capability or profit centre.

Over the course of 2018, SNDGG worked with the Ministry of Finance (MOF) to revise this resourcing approach, to facilitate the Government’s exploitation of technology. MOF has now implemented a new resourcing framework to enable more agile digitalisation, allowing for nimble initiation of pilots and proof-of-concepts, to test hypotheses or assumptions before scaling. To date, about 40 projects have received funding through this framework. Some interesting ideas include a computer vision-powered drowning detection system, and speech-to-text software.

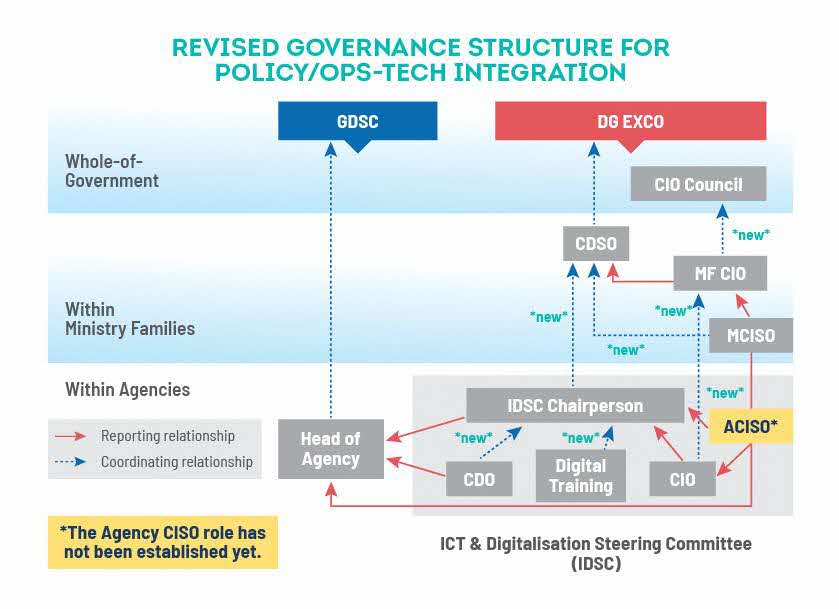

If we are to digitalise effectively, the process of integrating policy/ops with technology must also be improved. Good policy/ops-tech integration happens when the policy/ops communities and technologists know how technology can best be applied to achieve agencies’ missions, and work together to achieve them. The lack of policy/ops-tech integration today is reflected in anecdotes of designers and engineers complaining about “announcement-driven development”, which happens when they are committed to project deliverables—without prior consultation—by their policy counterparts. Business owners often decide on the solution before the technical team of designers and engineers has done its user research.

To improve ops-tech integration at the highest level, we have revised organisational structures. We have appointed a Chief Digital Strategy Officer (CDSO) at the Deputy Secretary level in every Ministry, to oversee delivery on their Ministry’s DGB targets and digitalisation plans. The CDSO is supported by the Ministry’s CIO, to encourage management-level conversations on how technology can support business needs. The CDSO also coordinates and has clear lines of authority over the ICT and Digitalisation Steering Committees within their Ministry, which also involve agencies’ CIOs, Chief Data Officers and Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs).

Beyond structures, policy/ops-tech integration can be achieved if policy makers lay down clearly the outcomes they want to achieve or the problems they want to solve, and then give engineers sufficient autonomy to research and come up with technical solutions. We must develop solutions that are evidence-based and driven by user research.

One of the best ways to achieve policy/ops-tech integration is through agile software development, where policy or ops officers work closely with the technical team—and in some cases, are even co-located with them—and constantly iterate their solution through testing with users. This approach to software development is gaining recognition in the public service, and together with the growing awareness that digitalisation is a priority, we are witnessing an unprecedented opportunity to build an engineering culture in the public service.

A third example of a process we need more of is giving space to tech-push and whitespace projects. Tech-push goes beyond ops-tech integration and gives engineers freer rein in how to innovate. We have seen the value of tech-push: in fact, many of GovTech’s products and platforms were developed this way, without any business owner. Today, these products and platforms, such as Beeline and Moments of Life are well accepted and considered mainstream.

To structurally enable tech-push and white space innovation, SNDGG is starting a new digital experimentation and implementation unit. The unit will operate in a sandbox environment, where officers not only get to develop new products, but also test future directions for ICT policies, and try out new organisational approaches to building and running tech organisations—including in traditionally non-ICT areas such as HR and procurement. We expect this unit to model itself on how a modern tech organisation should look like, and to have its practices adopted by the rest of government where relevant.

A fourth set of process and structural changes that has been forged is having multi-functional, multi-agency teams to provide integrated services to citizens. The Government had previously experimented with this through the establishment of the Municipal Services Office and its OneService app, and more recently, the Moments of Life project. Unlike most task forces, which disband once they deliver a product, we need such teams to remain: because in the digital age products have to be constantly updated and upgraded beyond their “delivery” date. As a result, civil servants may increasingly find themselves part of matrix organisations, where they have a primary job, but also secondary jobs in such multi-agency task forces.

Civil servants may increasingly find themselves part of matrix organisations, where they have a primary job, but also secondary jobs in multi-agency forces.

The last example of change in SNDGG’s organisational construct is the designation of a functional leader or professional head of the Information and Communications Technology and Smart Systems (ICT&SS) community in the Government. This functional leader is the Government Chief Digital Technology Officer (GCDTO). The GCDTO will increase the coherence and lift the standards of the ICT&SS community through the creation of common concepts of operations, common platforms and technical standards, common competency frameworks and training, as well as a common HR scheme.

For greater coherence across the Government, SNDGG prioritises and brings together engineering resources across Government to work on large, complex but high-impact digital technology projects. These would include the aforementioned Strategic National Projects, though agencies retain the autonomy to commission other high impact projects that are largely within their domains and do not need whole-of-government coordination. SNDGG, working with MOF, evaluates the funding proposals for agencies’ projects to avoid duplication and to provide guidance on how to build the projects that do get approved.

For example, we have developed a Singapore Government Technology Stack, and want agencies to use components in the Tech Stack when developing their systems. The Tech Stack comprises various layers of component: the bottom layers are fundamental components such as data and infrastructure, and the upper layers comprise micro-services and applications. Agencies are encouraged to use what is centrally available and customise only at the upper layers.

The Tech Stack signals a departure from the way the Government has traditionally done software development. We are moving from monolithic to modular system architecture, and this saves time and effort in developing and maintaining digital services. It also greatly reduces the time-to-market for digital services since agencies don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Examples of projects built using components of the Tech Stack include the Business Grants Portal, MyCareersFuture and Moments of Life.

The Singapore Government officially adopted a commercial cloud-first policy in June 2018. We intend to migrate the majority of Government ICT systems to the commercial cloud over the next five years, as the cloud brings benefits such as access to best-in-class services for our engineers, lower hosting costs, and reduced system downtime.

Collectively, these efforts will achieve greater interoperability between and coherence across Government ICT systems. Standards of use, including cybersecurity, will be uplifted. At the same time, this strikes a balance between commonality of platforms and standards at the infrastructure layer and innovation at the application layer.

To build a Digital Government in support of a Smart Nation, we need a sizeable bench strength of skilled engineers. In particular, we want to hire specialists or peak technical talent, and engineers with experience managing big technology projects. We need to partner the private sector better, and reach out to citizens to make sure the design of our digital products and services are informed by actual experiences and user research. Smart Nation is ultimately a whole-of-nation effort, and we need the private and people sectors to play their part also.

To attract tech talent, GovTech’s HR scheme has been revised to match the attractive salaries tech talent would otherwise command in the private sector. We are also stepping up recruitment of overseas Singaporeans who have worked in technology companies, having organised Singapore Tech Forums in the Bay Area for the past two years. Through the Forum, we share how Singapore’s dynamic tech ecosystem can support their ambition, and that there are abundant opportunities whether they join the public or private sector here. We have a Smart Nation Fellowship programme that allows overseas Singaporeans who are working in the private sector to take a three- to six-month stint with us, to collaborate on digital or engineering solutions that will have an impact on people’s lives.

At the same time, we have to improve the management of tech talent within the Public Service. To this end, we have developed a common HR scheme for digital technologists, so that they can take on ICT&SS roles across different agencies to enhance their exposure and contribution. The scheme allows them to pursue leadership opportunities, either becoming a specialist or assuming a leadership role in an ICT&SS agency. A Talent Leadership Committee has been established in tandem, to more systematically groom and plan for succession for our talents and key ICT&SS positions. The Administrative Service has also established an engineering track that allows Administrative Officers to spend more time in engineering jobs to deepen their expertise. This is modelled after the Singapore Armed Forces Overseas Scholarship Scheme that allows officers more sustained stints on the ground to build deep expertise.

Our tech talent can join many agencies. SNDGG has established a Centre of Excellence for ICT&SS, comprising the C3 Capability Centre in the Defence Science and Technology Agency, the Geospatial Capability Centre in the Singapore Land Authority, and GovTech’s Capability Centres in five areas: Application Design, Development & Deployment, Data Science & Artificial Intelligence, Sensors & IoT, Government Cybersecurity, and Government Infrastructure. These Capability Centres and the talent within them have been crucial in rebuilding engineering capabilities within the government, and have been both the cause and result o f the Government being able to in-source ambitious and socially meaningful digital projects.

However, given the finite size of the Government’s ICT&SS workforce, we must go beyond the public sector to raise the capabilities of our partners in the private sector. We have been increasingly open to co-sourcing and sharing our approach to software engineering with the private sector, as well as encouraging them to build applications using components of the Singapore Government Technology Stack. In October 2018, we hosted our inaugural STACK Developer Conference, which saw 1,200 attendees—more than half of whom were from the industry. The feedback for STACK was positive, with attendees appreciating the Government sharing its technology roadmaps. We are targeting an even bigger Developer Conference in 2020.

We need to partner the private sector better, and reach out to citizens to make sure the design of our digital products and services are informed by actual experiences and user research.

This sharing is not one-way. Leading cloud service providers like Amazon, Google and Microsoft are not just supporting the migration of Government systems, but sharing best practices with our IT teams and helping to train and certify them. GovTech has also come up with a Digital Technology Attachment Programme, to let our engineers gain industry exposure through a short stint with partnering companies, and a Technical Mentorship Programme which matches our project teams with local or overseas technical mentors. I am glad to report that all mentorship opportunities with Silicon Valley-based mentors have been taken up.

Finally, becoming an effective digital government demands that we reach out to our citizens. MCI has programmes to raise the digital readiness of the public, and SNDGG co-creates with the public by involving them in user research for digital products, as well as getting them to test beta applications. Through a new programme, Smart Nation Co-Creating with People Everywhere (SCOPE), we partner agencies such as the People’s Association and the National Trade Union Congress, leveraging their outreach events to garner public feedback on products under development. We believe that this increases the ownership citizens feel towards these products, and makes them more inclined to use the products once they launch.

Conclusion

We are still in the early days of a long journey towards becoming a Digital Government and a Smart Nation. Most of the cutting edge innovations for digital technologies come from technology companies in the private sector. We have to make sure that the Government as a whole, and in particular GovTech, has top talent and is able to exploit technology on the same level as these top tech companies. There is strong political support for our work, and digitalisation is a key component of Singapore’s overall Public Sector Transformation. We also have a strong core of strongly committed officers in both SNDGG and across the ICT&SS community in the Government, who are passionate about this mission to make Singapore an outstanding city with the aid of technology.

But there is a lot more work to be done and challenges to be overcome. Although I am optimistic, a lot of hard work and commitment is still needed. On the surface, the public sector is a monopoly. There is no “Netflix” to disrupt us if we continue to operate like “Blockbusters”. But Singapore has no monopoly on the world stage—as a country we can be disrupted and left behind in geo-political and socio-economic terms. So we have to put pressure on ourselves, not by looking at other governments and how digital they are, but by looking at whether Singapore as a whole is economically and technologically competitive relative to other countries.

If we are serious about Digital Government setting the pace for Smart Nation, our agencies and the whole-of-Government must continually look for ways to raise our game, innovate, and use digital technology as a multiplier for our effectiveness. We have collectively created some momentum, delivered some good digital products, and less visibly, gone “under the hood” to change policies, raise capabilities, and modernise infrastructure. Let us build on what has been done, and accelerate the work.

NOTE

- Smart Nation Singapore, “Transcript of Speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at Smart Nation Launch, 24 November 2014”, accessed April 23, 2019, https://www.smartnation.sg/whats-new/speeches/smart-nation-launch.