Trends and Shifts in Employment: Singapore’s Workforce

ETHOS Issue 18 Jan 2018

Technological advancements and changing social norms are significantly altering the nature of work. Disruptive innovations have resulted in more jobs being displaced and more frequent bouts of involuntary unemployment. Digital platforms have made the coordination of components of work more seamless, timely, and convenient, thereby allowing work tasks to be unbundled. Such micro-jobs offer opportunities for workers to earn supplemental income, but come with less job security. Employers that value operational flexibility may favour contingent workers and reduce their core of permanent staff to optimise labour costs. Individuals are likely to experience more frequent career transitions across companies, sectors, and even types of employment, as new job opportunities emerge and existing jobs are redesigned. Workers will have to get accustomed to the prospect of less permanent and more fluid work arrangements throughout life.

A multi-agency approach

The “Future of Work” is a broad and complex topic, and major streams of work are on-going. In response to technological and economic disruptions, economic agencies and the Committee on the Future Economy (CFE) are looking into future areas of growth, job creation, and helping companies cope. The Ministry of Education (MOE) and SkillsFuture Singapore (SSG) are identifying the skills and training needed to keep Singaporeans relevant. At the intersection of jobs and skills are the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) and Workforce Singapore (WSG), which match individuals with the right skills to the right jobs.

How We Organise Ourselves for Work Is Changing

Recent statistics suggest that traditional permanent employment globally is fracturing. Meanwhile, alternative work arrangements such as contract-based employment, freelancing and self-employment1 are on the rise in the US, Europe, and Asia. Nearly one in four Europeans work independently,2 while one-third of Americans have done freelance work in 2015 alone.3 These trends are partly attributable to domestic labour market conditions, where a lack of viable permanent alternatives following the global financial crisis has resulted in elevated unemployment rates—particularly among youths—amidst a structural decline in labour force participation rates.4 Strong employment protection legislation for traditional employees in Europe also makes non-traditional workers relatively less costly and more attractive.5 The increase in non-permanent employment can manifest itself in different forms: while the UK has seen a rise in self-employment, the US and Germany have mainly experienced increases in term contract employment at the expense of permanent employment.

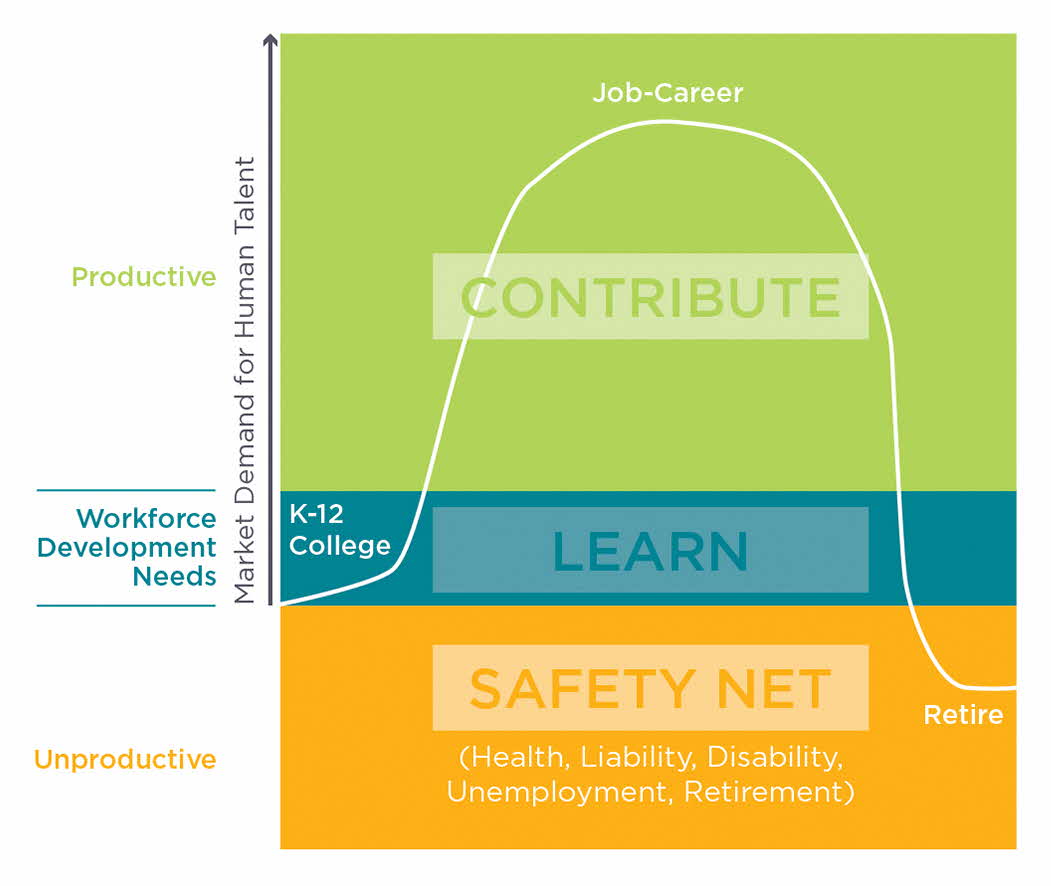

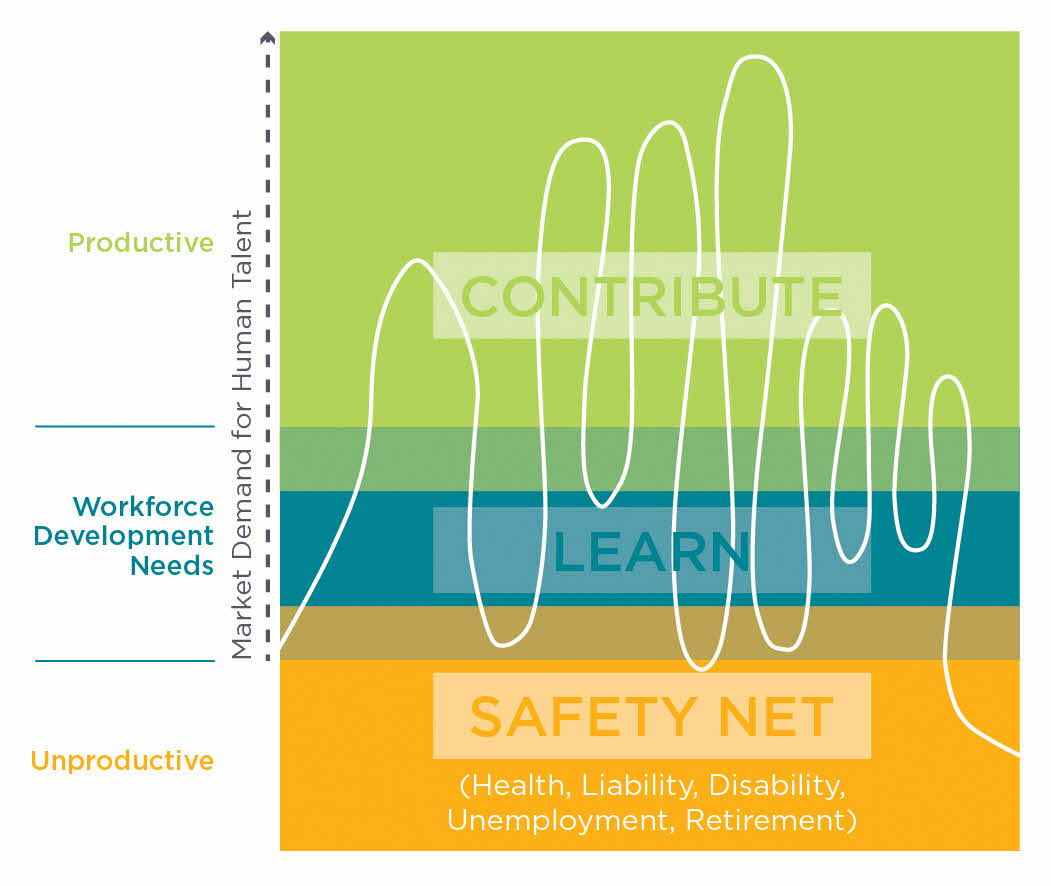

While Singapore has not experienced a decline in the share of permanent employment, workers may see a gradual shift away from the traditional model of lifetime employment. In future, we expect more transitions in and out of employment and learning during adulthood. Workers may move between different jobs, work arrangements, and even careers, punctuated by periods of unemployment or training (see Figure 1).

Source: @heathermcgowan and www.futureislearning.com

Figure 1. Comparison of Traditional and Future Models of Employment

Source: @heathermcgowan and www.futureislearning.com

Traditional Model of Employment

Future Model of Employment

Why has there been a shift away from traditional employment?

- Workers are more likely than before to work for multiple employers in their lifetime. While some do so voluntarily in search of better opportunities, others are forced to do so due to displacement arising from tech advancements, economic restructuring and/or shorter business cycles.

- The emergence of digital platforms is making it easier for individuals to freelance, whether as a primary or secondary source of income.6 The growth of freelancing in and of itself brings potential efficiencies to the economy, better experiences to consumers, and increases the range of choices available to the worker including job options that offer greater flexibility and autonomy and a source of supplemental income.

- Unbundling of jobs into disaggregated tasks, is becoming more commonplace. This trend can be traced back to the 1970s with the rise of outsourcing and contracting. Technology has fuelled the trend, by allowing jobs to be deconstructed and constituent tasks outsourced. A Mowat Centre report, for example, claims that work is being reduced: from lifelong to full-time or part-time jobs; from contract jobs to project jobs; and from task-based jobs to micro task-based jobs. Eventually we may transition to hybrid tasking paired with artificial intelligence or complete automation. In the process each reduction in job scope is associated with a decrease in pay for workers. Hence, as jobs are unbundled, workers may see their wages fall, and over time they may even lose their jobs altogether.7

Many of our existing policies have operated on the assumption of employer-employee relationships as the norm. As a result, many freelancers fall outside some of our social safety nets.

The Freelancing Phenomenon

The freelancing phenomenon or gig economy has captured significant attention globally. Freelancing can be seen as healthy as long it is voluntary and chosen by workers due to the inherent merits of the job (e.g., flexibility and autonomy) rather than due to labour market inequities (e.g., disadvantaged working conditions that make freelancers cheaper than permanent employees).

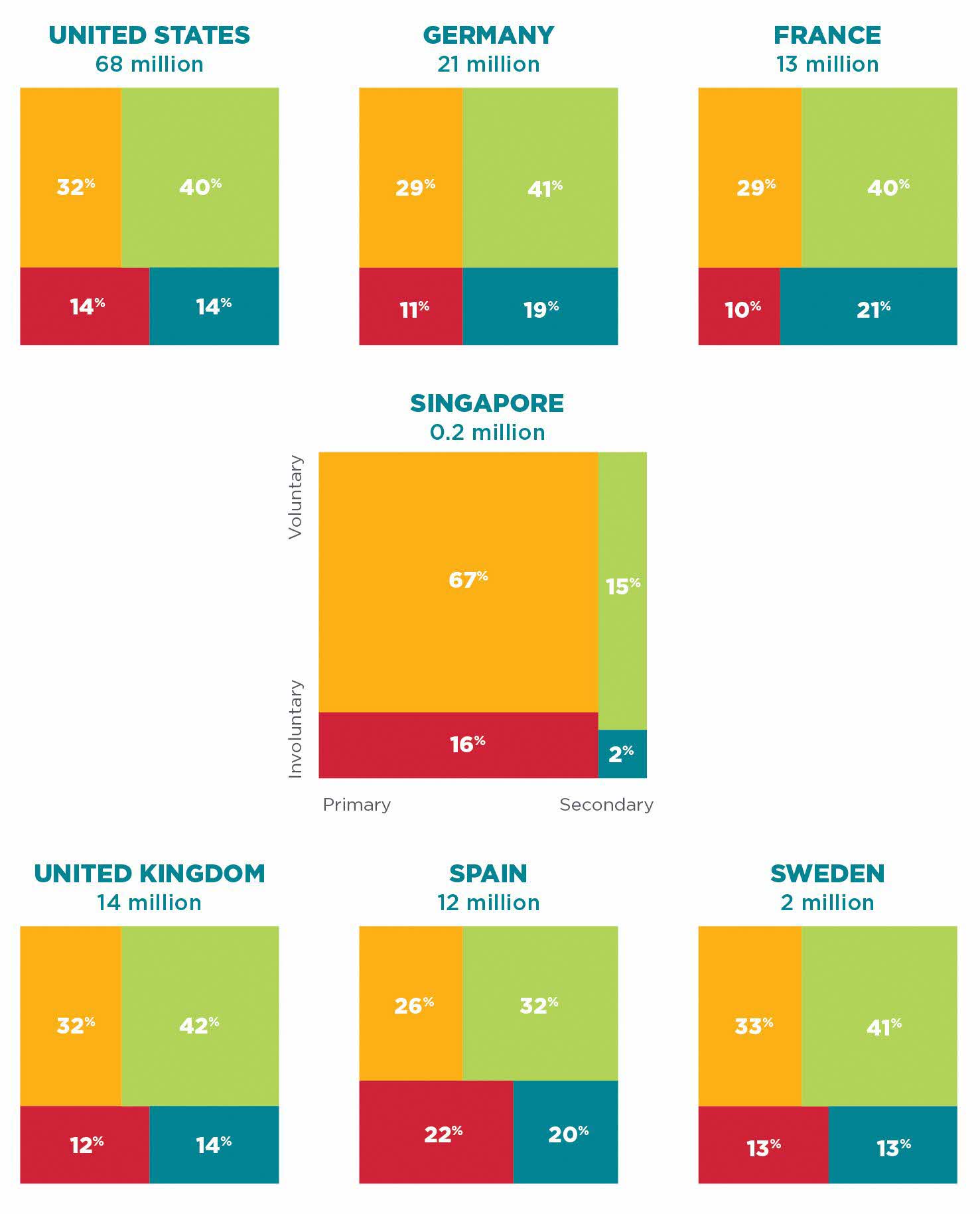

In Singapore, 82% of all freelancers do so by choice, a much higher proportion relative to other developed countries (see Figure 2). However, these proportions may change over time.

Proportion of Primary and Secondary Freelancers/Independent Workers Who Do So Voluntarily

Notes

- Figures for Singapore are from Supplemental Labour Force Survey 2016 and refer only to freelancers.

- Figures for other countries are from McKinsey Global Institute's 2016 report, "Independent Work: Choice, Necessity, and the Gig Economy" and refer to independent workers, which is a broader group compared to freelancers.

- Figures below country headers denote number of such workers in each country.

Preparing for the Future of Work

The changing work landscape calls for new perspectives and responses to work and the organisation of work. At the same time, Singapore should continue to hold steadfast to three principles:

- First, our ongoing strategy must be to keep the labour market flexible, tight, and responsive.

- Second, we must continue to pro-actively invest in skills upgrading, lifelong learning, and to facilitate employment efficiently and effectively.

- Third, we should not and cannot stop the rise of digital platforms and the “gig” economy, such as represented by platforms like Uber and Upwork.

Concurrently, we need to build anticipatory capacity to understand how future work arrangements will impact workers and society, and take steps to prepare ourselves for them. Going forward, disruptions to work arrangements are likely to have more frequent and deeper effects on all workers, including permanent employees, term contract employees, as well as primary and secondary freelancers. Many of our existing social and economic policies have operated on the assumption of employer-employee relationships as the norm. As a result, many freelancers fall outside some of our social safety nets. To address this, we will need to consider two key challenges:

- Enhancing social security and basic worker protections for freelancers: How can we bring freelancers into our policy architecture so that social security, worker protections and other social and economic policies are extended to freelancers?

- Ensuring industrial harmony amidst changing labour arrangements: Job instability can weaken our social compact and undermine social cohesion; how can we extend measures to ensure industrial harmony with freelancers?

New models of work are prompting changes to the traditional employer-employee relationship.

Enhance Social Security and Basic Worker Protections for Freelancers

New models of work are prompting changes to the traditional employer-employee relationship. The shift away from employer-employee relationships drives a wedge through our existing social and economic policies, which have been tied to the conventional idea of permanent employment.

Over time, more workers may take on either primary or secondary freelancing, or both, at some point in their lives. We may need to relook our social security and worker protection laws to ensure a basic level of assurance for such freelancers. In doing so, our intention should not be to shield freelancers from market risks, such as volatility in the volume of work or from competition, or from new digital ways of sourcing for work. Neither should we import wholesale the full suite of employee protections that are in place, such as over-time and rest-day protections. Nonetheless, freelancers deserve basic protection from non-market risks, no different from traditional employees.

In particular, savings for healthcare, housing, and retirement are as important for freelancers as traditional employees. To do this, however, we first need to better enable the collection of Medisave contributions by Self Employed Persons (SEPs), almost a quarter of which lapse today.1

Our intention should not be to shield freelancers from market risks.

Leverage on a National Platform for Job Payments and Policy Implementation

A key problem freelancers face today is timely payment for their services. This affects downstream cashflows, particularly for one-person setups in industries like media and copywriting. Written contracts would help, as would affordable mediation services. Also, a national platform to track the collection and payment of these invoices would enable freelancers to better manage their cashflows and financial obligations.

Furthermore, a wide range of public services are means-tested today. To reduce the administrative burden on the Government to validate each application and appeal individually, a national platform could enable freelancers and other SEPs whose incomes are not otherwise captured to become eligible for schemes such as Workfare, housing grants and loans, education bursaries, childcare and kindergarten subsidies. NSMen and parents with young children who are SEPs would no longer need to file their income claims manually when applying for makeup pay and government paid maternity/paternity leave. In addition, primary freelancers could become eligible for government grants targeted at employers.

Nonetheless, freelancers deserve basic protection from non-market risks, no different from traditional employees.

Work Injury Insurance Coverage for Freelancers

A unique feature of the “contract for service” model is that freelancers have significant autonomy and control over how the service is performed. Because corporate service buyers and intermediaries, unlike employers, do not traditionally exercise significant control over how freelance work is performed, freelancers are excluded from the protections accorded by legislations such as the Employment Act, Employment Claims Act, and Work Injury Compensation Act. Freelancers generally accept such a tradeoff because they value the autonomy of determining which jobs and assignments to accept. While some workers are misclassified as freelancers, their concerns can and are being addressed by existing programmes such as WorkRight.2

One major pain point of freelancers is their exclusion from the Work Injury Compensation Act despite being subjected to similar work injury risks as regular employees. Freelancers who are injured in the course of their work do not receive paid medical treatment, have to dip into their own savings during the period they are unable to work, and will not receive any compensation for loss of future earnings arising from any permanent incapacity.

Instead of having service buyers of different sizes purchase various insurance types for individual freelancers, one approach could be for freelancers to be insured themselves, before they can bid on contracts. Freelancers may work for many different service buyers or platform intermediaries with (often concurrent) contracts of varying size and duration, and this would be a more practical approach. This also levels the playing field amongst freelancers and ensures that they do not under-cut each other to win contracts on the basis of risk-appetite in relation to work injuries.

Freelancers should also be allowed to benefit from the collective representation that trade unions provide.

Ensure Industrial Harmony amidst Changing Work Arrangements

Singapore has enjoyed a long track record of industrial harmony. To remain relevant, tripartite partners will have to expand their representation coverage beyond existing constituents as work arrangements change and worker profiles shift to include freelancers.

One area that we may have to consider in the future is whether freelancers should also be allowed to benefit from the collective representation that trade unions provide. This is so that freelancers would not have to bear the responsibility of negotiating work terms on their own, and face asymmetrical bargaining power with service buyers.

Notes

- Based on CPFB’s data on registered SEPs who are liable for Medisave contributions as at 31 December 2016 (i.e., have outstanding MA liabilities and earn annual net trade income above $6,000).

- Ministry of Manpower, “WorkRight: Know Your Employment Rights”, November 22, 2017, accessed December 12, 2017, http://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/employment-act/workright.

NOTES

- Sarah A. Donovan, David H. Bradley, and Jon O. Shimabukuru, “What Does the Gig Economy Mean for Workers?”, Congressional Research Service, February 5, 2016, accessed November 22, 2017, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44365.pdf.

- Euro Freelancers, “EU Affairs Freelancers Association”, accessed November 22, 2017, http://www.euro-freelancers.eu/eu-affairs-freelancers-association/.

- Upwork and Freelancers Union, “Freelancing in America: 2015”, accessed November 22, 2017, https://www.upwork.com/i/freelancing-in-america/2015/.

- Eurofound, Recent Developments in Temporary Employment: Employment Growth, Wages and Transitions (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2015), accessed November 22, 2017, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/homef.

- COEURE, “EU Dual Labour Markets: Consequences and Potential Reforms”, June 8, 2015, accessed November 22, 2017,https://coeure.eu/.

- Secondary freelancers include regular employees who moonlight on the side, or students, housewives or retirees who may wish to fill idle hours and supplement their income. Secondary freelancers constitute only 17% of all freelancers in Singapore. But their numbers may grow if fluid work arrangements become more prevalent.

- Sunil Johal and Jordann Thirgood, “Working without a Net: Rethinking Canada’s Social Policy in the New Age of Work”, Mowat Centre, accessed November 22, 2017, https://mowatcentre.ca/working-without-a-net/.